Some architects favour writing about architectural theories. Some architects prefer not to write at all and only leave their buildings to posterity. Mr. Yang Cho-cheng (楊卓成), Master of Chinese Classical Architecture, belonged to the latter. His writing is extremely rare to come across. One day in the 90s, Mr. Yang gave an unfinished draft of his writing to Soong Shu Kong to rectify and encourage him. The title of the article is: “Chinese Architecture and the National Chiang Kai-shek Cultural Centre.” It has been treasured by the recipient like priceless jade discs for decades. He is aware that even though it is an incomplete writing on a few sheets, they are no less than precious pearls in a storm-tossed world. The principles of Chinese Classical Architecture and the design concept of the National Chiang Kai-shek Cultural Centre are narrated in this piece of writing. It is indeed an important document in the studies of Chinese Classical Architecture. Its publication now may be helpful to its preservation.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

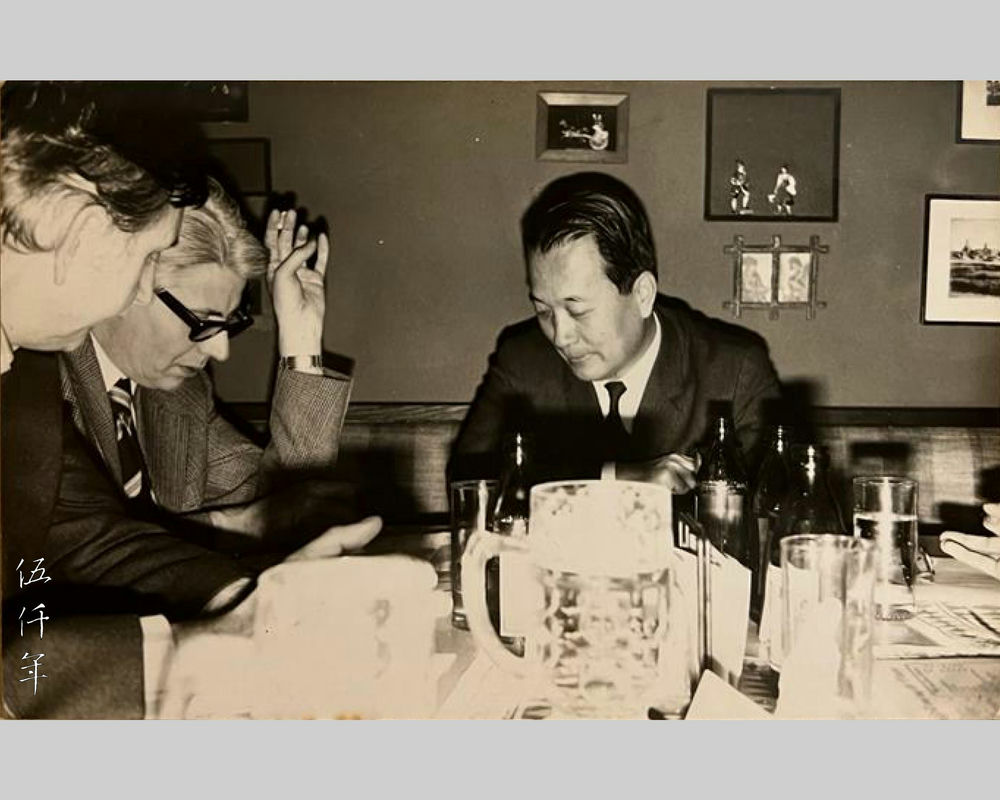

Mr. Yang Cho-cheng meeting overseas consultants. Photograph formerly in the collection of Mr. Yang Cho-cheng

With China’s long history and vast territory, it is very difficult to search for the roots of Chinese Classical Architecture amidst such voluminous background material. The traditional culture of the Chinese race, after thousands of years of assimilation, has pivoted around Han ethnic culture from the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River, and the cities of Ch’ang-an (長安), Lo-yang (洛陽), Peking (北京). In short, from the Chou dynasty (周朝) onwards, in a span of over two thousand years, the centre of the first one thousand years was Ch’ang-an, the centre of the next one thousand years was Peking.

Peking was the imperial capital for hundreds of years. The distinctive characteristics of the city resulted from its compliance with the planning and architectural standards developed over four thousand years in China. To compare the well known classical architecture of Peking with the classical architecture of other famous international cities, such as Rome and Paris, they are set apart by a certain expansiveness and grandeur, replete with Chinese classical aesthetics. The classical architecture of Peking fully conveys the expressivity of Chinese culture.

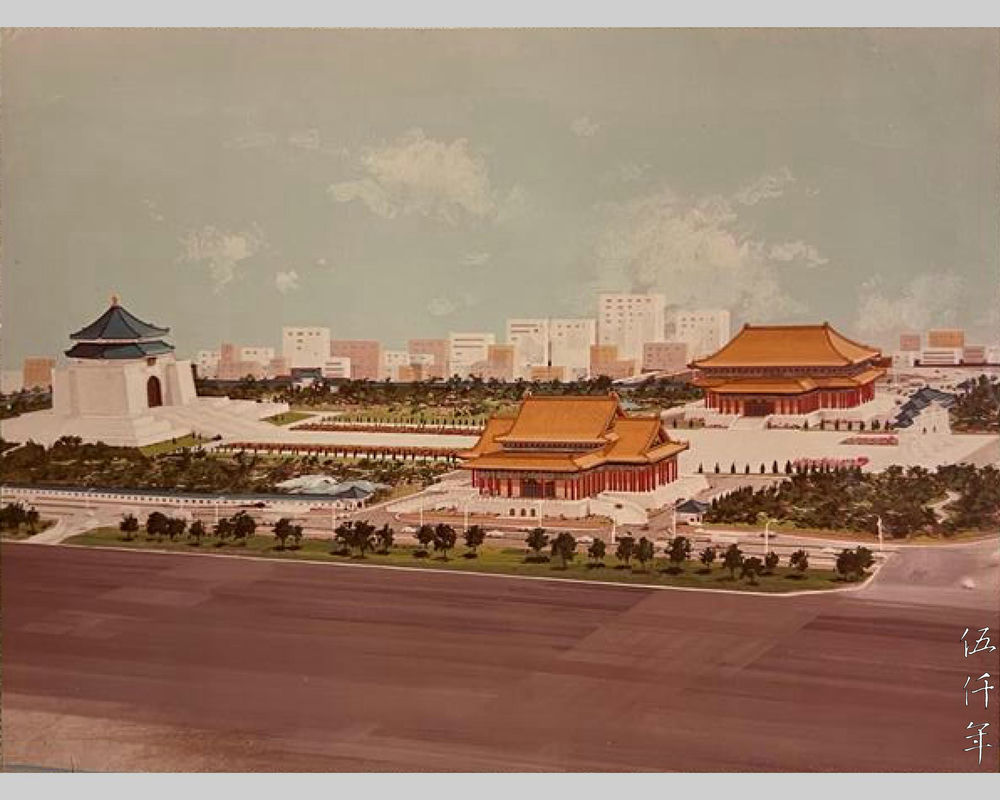

Perspective drawing of the National Chiang Kai-shek Cultural Centre. Photograph formerly in the collection of Mr. Yang Cho-cheng

Bird’s eye view of the National Concert Hall in the foreground and the National Theatre in the background. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

Front elevation of the National Theatre. Photograph courtesy Wikipedia

Front elevation of the National Concert Hall. Photograph courtesy Wikipedia

Regarding the designs of the National Theatre and Concert Hall in the National Chiang Kai-shek Cultural Centre in Taipei, the appearance of the National Theatre resembles the Hall of Supreme Harmony (太和殿) in the Forbidden City in Peking, and the appearance of the National Concert Hall resembles the Hall of Preserving Harmony (保和殿) in the Forbidden City in Peking. The National Theatre and Concert Hall in Taipei both comply by the guidelines of Chinese Classical Architecture, they adhere to the rules of the tou-kung system (斗拱 column and beam bracket system), the proportions are specified to configure their structural frames. The Hall of Supreme Harmony has a hip-roof (廡殿頂) and the Hall of Preserving Harmony has a hip-and-gable roof (歇山頂). The lengths, widths and heights of their interiors are very different, determined by their separate functional needs.

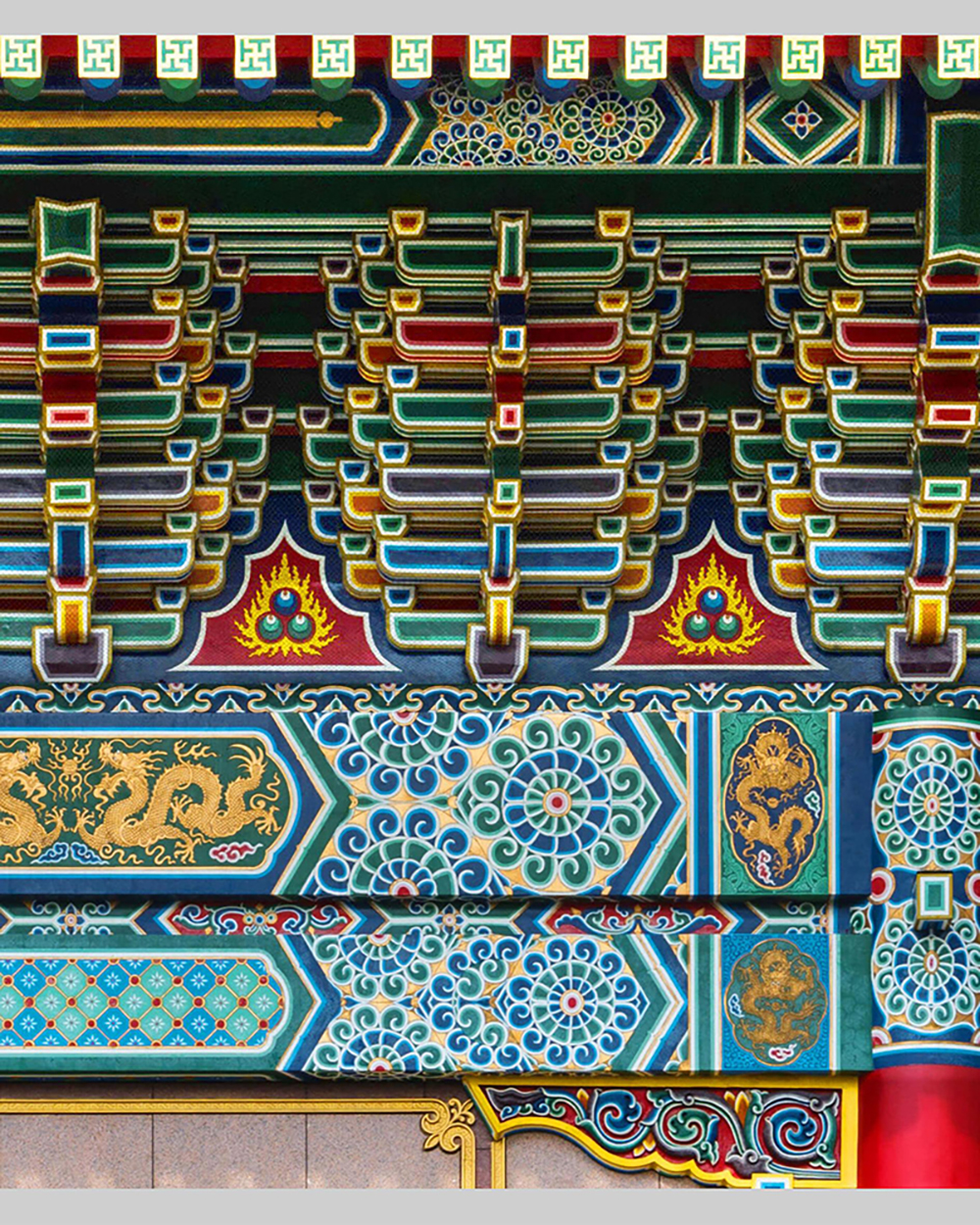

The column and beam bracket system of the National Concert Hall. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

The column and beam bracket system of the National Theatre. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

In Chinese Classical Architecture strict rules are applied to coordinate the proportions of different architectural parts, hence the proportions of the buildings remain consistent. This is nevertheless not design imitation, it is the inevitable result of design by rules. If the rules of Chinese Classical Architecture are compromised, then its aesthetics will be ruined. In Western Classical Architecture, there are precise rules too, based on the proportions of columns, whilst Chinese Classical Architecture is based on the proportions of the tou-kung system (column and beam bracket system). As a consequence, the aesthetics of Chinese Classical Architecture and Western Classical Architecture can withstand the test of time, undiminished in beauty and appreciated through the ages, for they are both steeped in their respective cultural traditions.

Sculptural figures on the roof ridge of the National Concert Hall. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

Sculptural figure of a dragon head known as cheng-wen on the roof of the National Theatre. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

The plan of Chinese Classical Architecture is inclined towards symmetry, similar to the symmetry of the human body. An external feature is the glazed coloured roof, not only are the colours appealing, the glazing also protects the ceramic tiles, resists weathering, reflects light and heat. The curvature of the roof is dictated by architectural rules, the form is graceful, and moderates rainfall. The ridge near the cornice is decorated with sculptural figures of fairies and beasts, they are vigorous in form and enhance the notion of auspiciousness. Most important they are used to cover nail holes, and prevent water seeping in. Trailing the sculptural figures upwards, the tiles of the ridge rise, there is a larger sculptural figure of a beast, and trailing further upwards, where it encounters the main ridge, there is a sculptural figure of a dragon head named cheng-wen (正吻). A decorative sword is affixed to the cheng-wen to achieve visual balance.

In time, architectural details only differ slightly in different dynasties. The overall framework remains the same. According to historical documentations, the more recent the history, the finer the details, the more meticulous the specifications, the more developed the system. The designs of the National Theatre and the National Concert Hall in Taipei are in accordance with the Ta-Ch’ing hui-tien (大清會典 Encyclopedia of Jurisdiction and Administration Matters of Great Ch’ing), and Ch’ing-shih ying-tsao tse-li (清式營造則例 The Principles and Rules of Construction in Ch’ing Style).

Chinese Classical Architecture is mostly surrounded by corridors (迴廊). The tou-kung system (column and beam bracket system), the secondary beams (桁) and purlins (椽) under the eaves of corridors are layered on each other to create visual distance. Looking from afar, the corridor is attributed with spatial depth. In Chinese Classical Architecture, the four corners of the roof resemble wings ready for flight, they are particularly dynamic. To compare a Chinese traditional roof with a Western traditional roof, the former is notable for its perceptible sense of movement.

Corridor and stone platform of the National Theatre. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

Corridor and stone platform of the National Concert Hall. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

Most of the grand classical buildings in the West use stone for construction, while the main structures in Chinese Classical Architecture primarily use wood. Chinese civilization developed in the Yellow River basin, this sienna plain was covered with thick forests, making it easy to source building material. To protect wood from rain and termites, paint is used for protection. In the beginning, single coloured paint was used, after many years of evolution, various coloured paints were used, and eventually the art of painting was introduced into architectural decoration. The tou-kung system (column and beam bracket system), the purlins under the eaves, the columns and beams that appear in the middle, are all painted with strong contrasting colours, to attain the perception of spatial distance, visual stimulation, and aesthetic appeal. As the vibrant colours are well coordinated, they can instead achieve a harmonizing effect. Chinese classical building sits on a stone platform (臺基) for visual stability. At the same time, because of the tall roof and the upwardly projecting roof corners, the platform should be proportionally compatible, with sufficient height to achieve visual balance and solidity. The main function of the platform is to separate the building from the ground to evade termites.

There are not many design variations for the wall in Chinese Classical Architecture. A common design feature is to affix relief carvings related to historical tales onto the wall. Yet for doors and windows, there are innumerable designs, their shapes and forms are each different. Various door types include leaf door (門扇), screen door (屏門) and arch door (拱門). Both doors and windows have fine carvings, their design variations are wide-ranging. The simple wall thus becomes far more dynamic.

Gable wall of the National Concert Hall. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

Colour is a vital feature in Chinese Classical Architecture. To visualize the multi-coloured roof tiles, the cyan coloured beams and square columns, the vermilion coloured round columns, the white stone platform and balustrades, standing under the blue sky and the white clouds, the spectacle is vivid and picturesque, a rival to the splendour of natural scenery. This architecture is sedate and languid in its outlook, it has a unique style, different to all others.

Architectural arch of the National Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

At the site entrance of a Chinese classical building, a p’ai-lou (牌樓 architectural arch) is frequently located. It is placed there to emphasize the notion of a doorway, to create spatial depth for a person walking towards the building, to visually frame the building, and to make the architectural experience more complex and interesting. Some objectives of designing an enclosed Chinese garden are to attain pastoral pleasure, to encapsulate the serenity of nature, to detach the spirit from the dusty world. With regard to the landscape design of the National Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, the flower beds and lawns on either side of the Memorial Avenue were designed to reinforce the solemn and dignified atmosphere of the Memorial Hall.

Caisson ceiling in the National Theatre. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

Detail of caisson ceiling in the National Theatre. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

For those projects in the style of Chinese Classical Architecture undertaken by my architectural office, they seek to reduce and simplify the intricacies of Classicism, while keeping the essential elements. Some examples are the ceiling and tsao-ching (藻井 caisson ceiling) of the interior, they are designed to appear simpler and lighter. Although the tsao-ching has not been embellished with extravagant materials, it is nevertheless refined and majestic. The main hall is designed to be spacious and grand, the tsao-ching is suspended in the middle with decorations of dancing dragons and phoenixes, acquiring the aura of auspiciousness. The walls of the main hall are decorated with fine paintings, relief carvings and palace lanterns, with bonsai located in between. The ambience of the main hall is tranquil, elegant and classical.

There are strict rules for all the architectural elements in Chinese Classical Architecture. The most important component is the tou-kung system (column and beam bracket system). To design the tou-kung system, the first step is to work out the heights and curvatures of the roof, the eaves, the eave corners, etc. Then according to the length, width and height of the building, the proportions of the tou-kung system and other architectural parts can be derived. This is the way to convey beauty in Chinese Classical Architecture. In the past, there were craftsmen who specialized in the construction of palace architecture. Their knowledge was passed down from generations of apprenticeships. In the Sung dynasty, Li Ming-chung (李明仲) wrote Ying-tsao fa-shih (營造法式 The Techniques and Rules of Construction) in thirty six volumes, and in early Republican era, Liang Ssu-ch’eng (梁思成 1901-1972) wrote Ch’ing-shih ying-tsao tse-li (清式營造法式 The Techniques and Rules of Construction in Ch’ing Style). These reference books document in detail the design and construction of Chinese Classical Architecture, such as the main palace hall, the rear palace hall, the circular hall (Temple of Heaven), the civilian buildings with multi-pitched roofs, the pavilions and many others.

Today in the Republic of China, buildings related to tourism and memorials are still attached to millenniums of Chinese culture. They are designed and constructed in the style of Chinese Classical Architecture, abetting the preservation of Chinese heritage. The unique aesthetics of Chinese culture, altogether different to Western culture, is especially fascinating to overseas visitors.

Since building materials and building technologies have advanced tremendously, a modern interpretation of Chinese Classical Architecture should preserve its traditional magnificence, at the same time, attain a level of comfort expected of modern living. The unique style of Chinese Classical Architecture has been universally appreciated, it is a part of Chinese heritage, and should continue to develop and flourish.

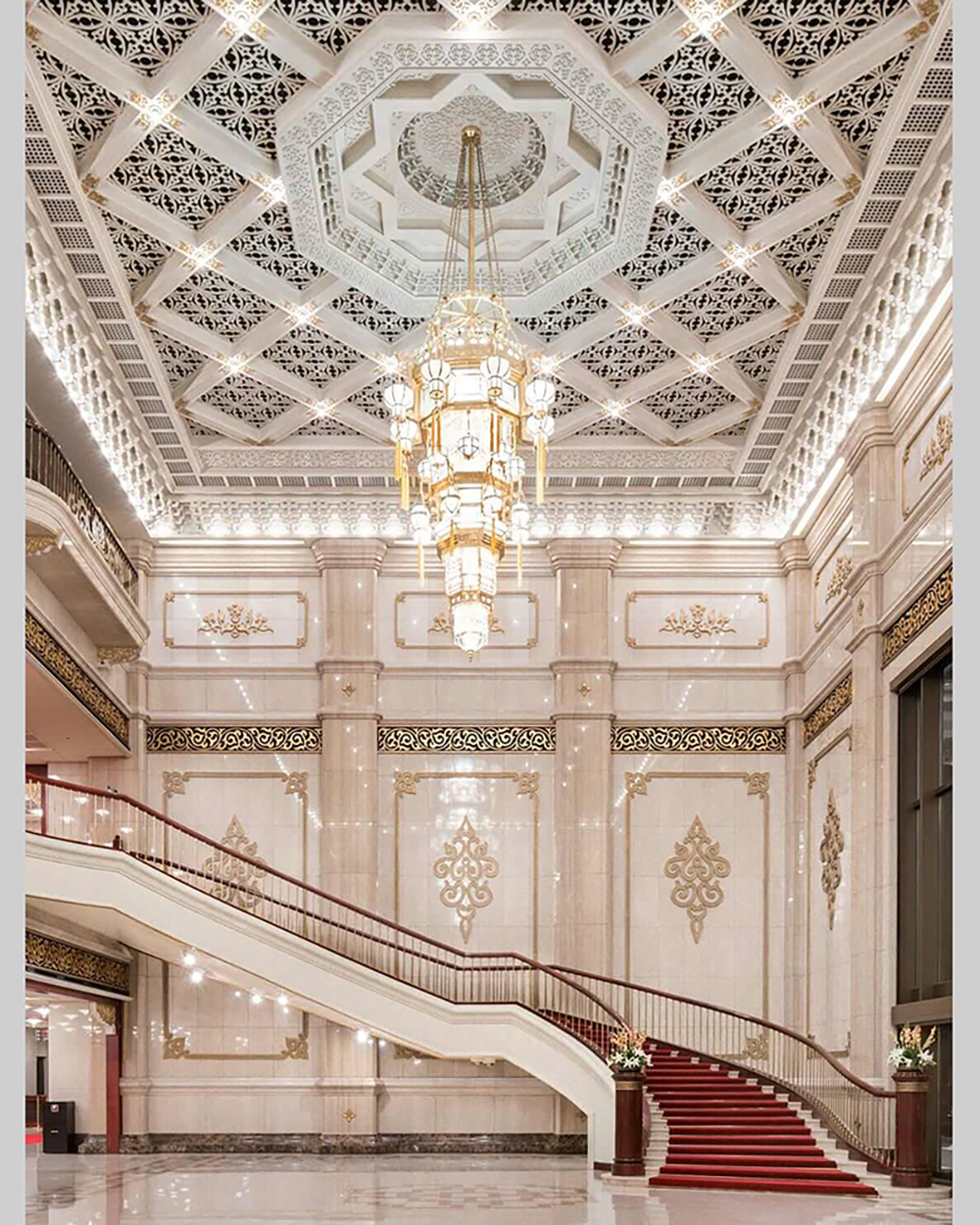

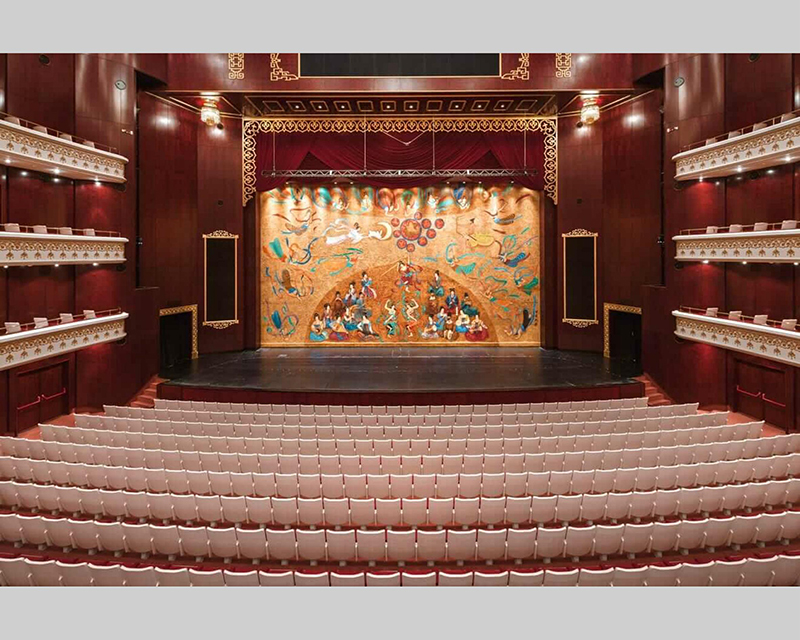

Interior of the National Theatre. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

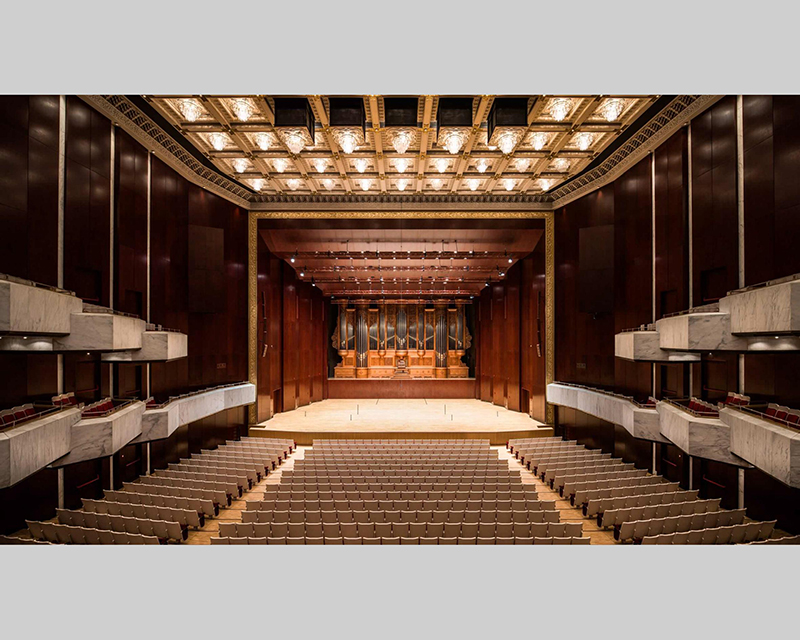

Interior of the National Concert Hall. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

The success or failure of a theatre, or a concert hall, mainly depends upon the quality of its acoustics. For the National Theatre and Concert Hall in Taipei, their superior acoustics have been endorsed by many leading musicians, opera singers and actors who performed there. They have also been commended by specialist journals in Britain, the United States and Canada, including CUE Technical Theatre Review, an authoritative British magazine on theatre, which featured the National Theatre and Concert Hall in Taipei on its front and back covers.

Interior wall detail of the National Concert Hall. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

Acoustics rely solely on the reflections of walls, ceiling and floor. In order to attain natural acoustics without using microphone, sound should be delivered with equal clarity to the audience in the front row and the back row. The most important acoustic condition to consider is the reverberation time (RT). The reverberation time for the National Concert Hall is 2 seconds, and the reverberation time for the National Theatre is 1.4 seconds. The reverberation time for the National Theatre is less because in theatre performances, more dialogues take place. With such reverberation times, the audience will not come across dry sound and will discern adequate spaciousness in the sound.

Performance halls must have excellent sound insulation, they cannot be affected by external noises. Performers can then fully produce the finest sounds their abilities are truly capable of. Many leading performers are unwilling to use performance halls with inferior acoustics, to avoid compromises to their musical standards and reputations.

Before the completion of the National Theatre and Concert Hall in Taipei, many distinguished international musicians deemed these three performance halls had the finest acoustics:

1. The Wiener Musikverein in Vienna. Opened in 1870. Its reverberation time is 2.05 seconds.

2. The Royal Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. Opened in 1888. Its reverberation time is 2 seconds.

3. Symphony Hall in Boston. Opened in 1900. Its reverberation time is 1.8 seconds.

The performance halls above were all built over a hundred years ago. Now the National Theatre and Concert Hall in Taipei have also been ranked among the international performance halls with the finest acoustics. In other words, since the beginning of the 20th century, despite the innumerable theaters and concert halls that have been built all over the world, no matter the amount of construction costs they have entailed, none surpass the acoustics of the National Theatre and Concert Hall, and none has been recognized as such.

Many tourists visit the National Chiang Kai-shek Cultural Centre. It will perhaps be a gratifying performance for the tour guide to shout inside the performance halls to demonstrate their reverberation times. The ideal reverberation time is a difficult task to accomplish, a slight inaccuracy turns it into an echo. An echo is a series of disconnected sounds, a reverberation is a series of connected sounds. If the reverberation time varies by 0.4 second from the specification, it is of little value.

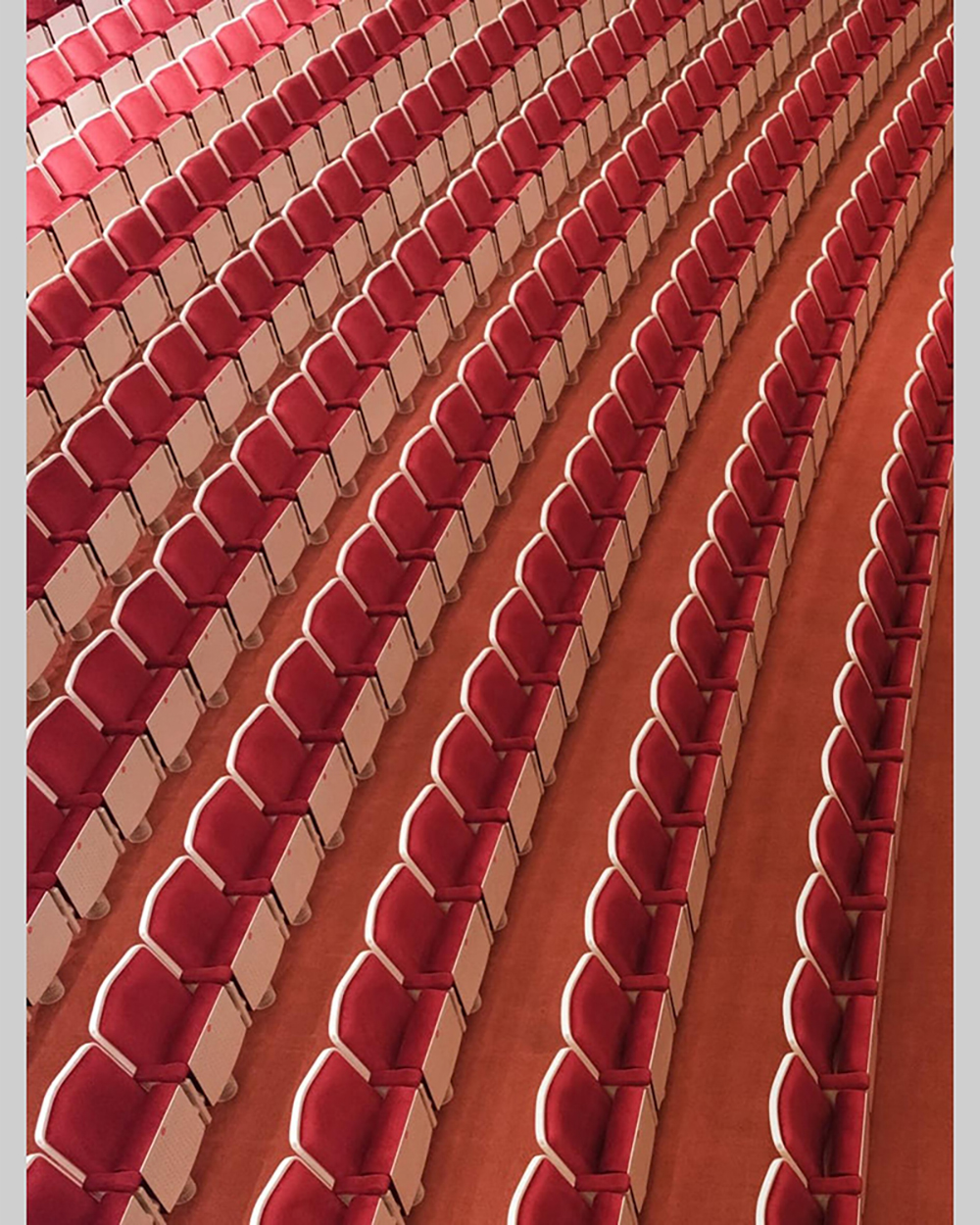

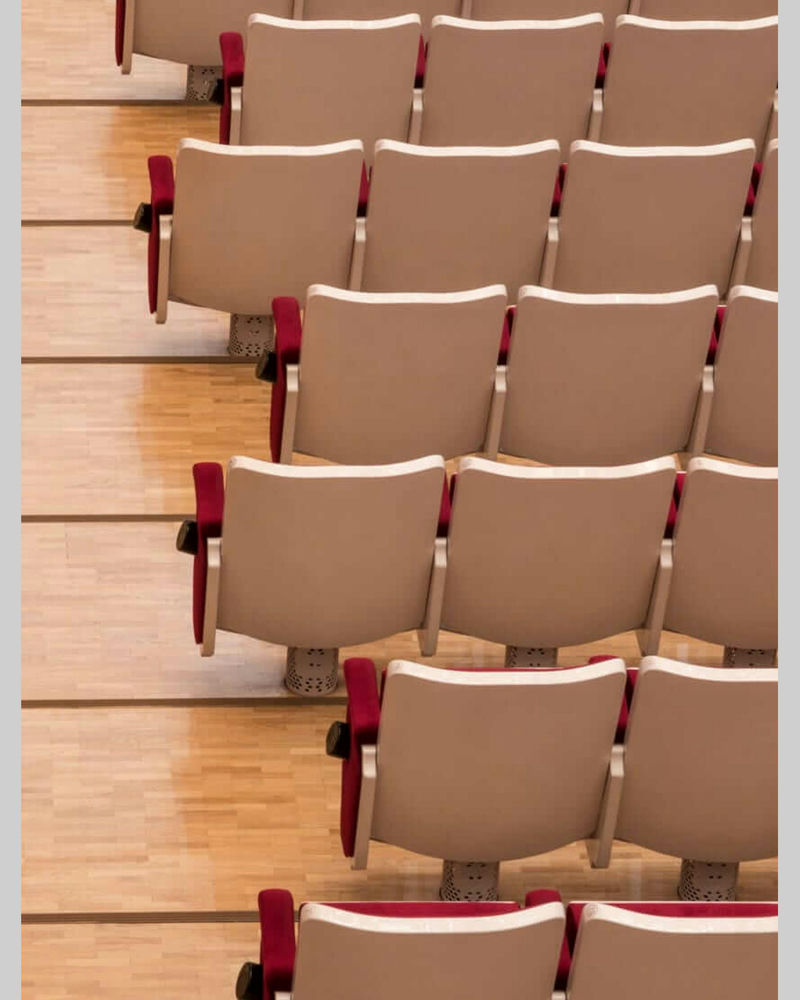

Seating arrangement in the National Theatre. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

The seating capacity of the National Theatre is 1,526, and that of the National Concert Hall is 2,074. Rows of staggered seatings provide better sightlines for the audience. The wall materials are the same for the National Theatre and the National Concert Hall, but the shapes and angles of the surface material are different. There are shallow triangular reflective panels on the side walls of the National Concert Hall. For the side walls of the National Theatre, the panels are even. To fulfill different acoustic requirements, carpet was installed inside the National Theatre to absorb some of the sound and reverberation, while wooden floor was installed inside the National Concert Hall to reflect sound and reverberation, thereby increasing the reverberation time.

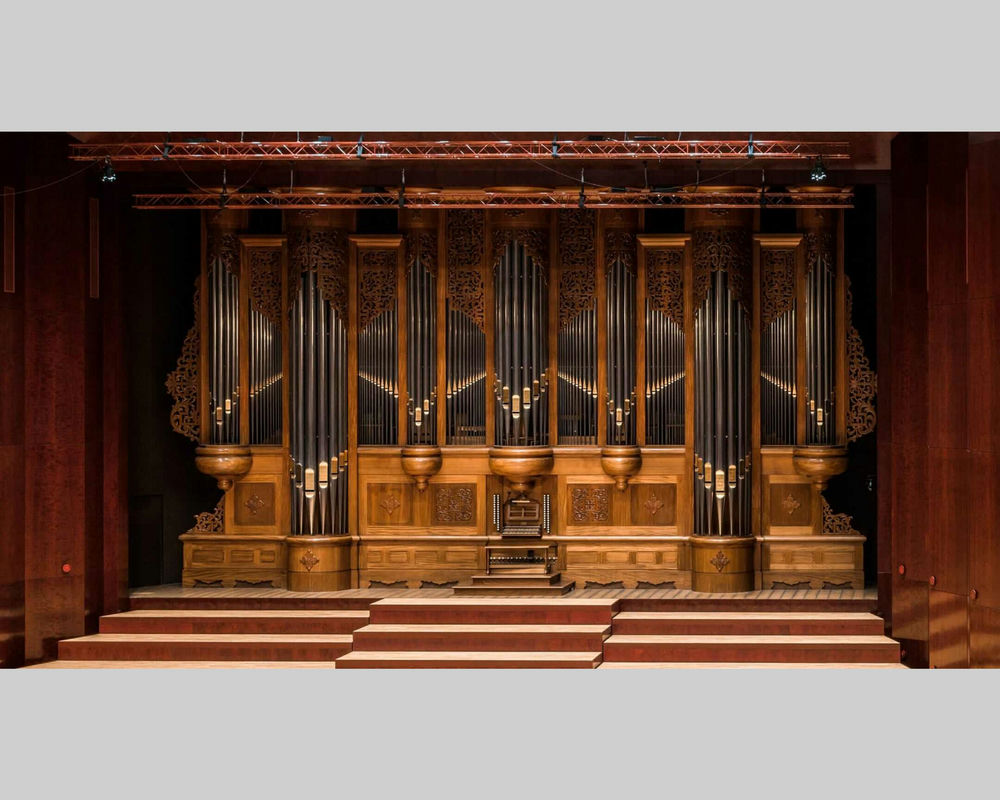

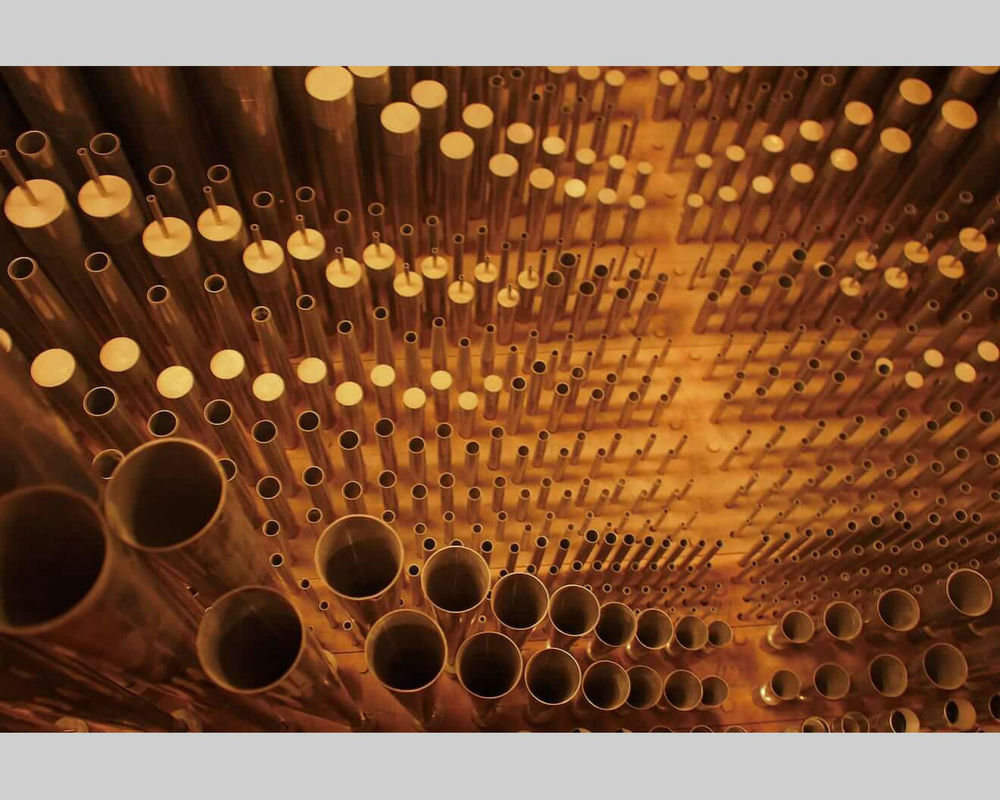

Organ instrument in the National Concert Hall. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

Detail of organ instrument in the National Concert Hall. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

The organ instrument at the back of the stage in the National Concert Hall was designed and built for the use of symphony orchestras. In the future, when distinguished orchestras are invited, they can be informed beforehand of its availability, and they can come with their organists. This will be refreshing for the audience.

Outlet diffuser vents under audience seats in the National Concert Hall. Photograph courtesy National Theatre and Concert Hall

Outlet diffuser vents of the air-conditioning systems are located under the audience seats of the National Theatre and Concert Hall. The outlet diffuser vents are in the form of circular grille columns, which are also the sole supports of the seats. The grilles are perforated with small holes, and the air slowly blows out from them. No sound comes from the outlet diffuser vents. The comfort zone of the air-conditioning systems was designed to reach head height. Hence the refrigeration ton of the air-conditioner condenser units is much lower than their counterparts, only consuming half of the customarily required energy. (End)

A Selection from the Book Collection of Mr. Yang Cho-cheng

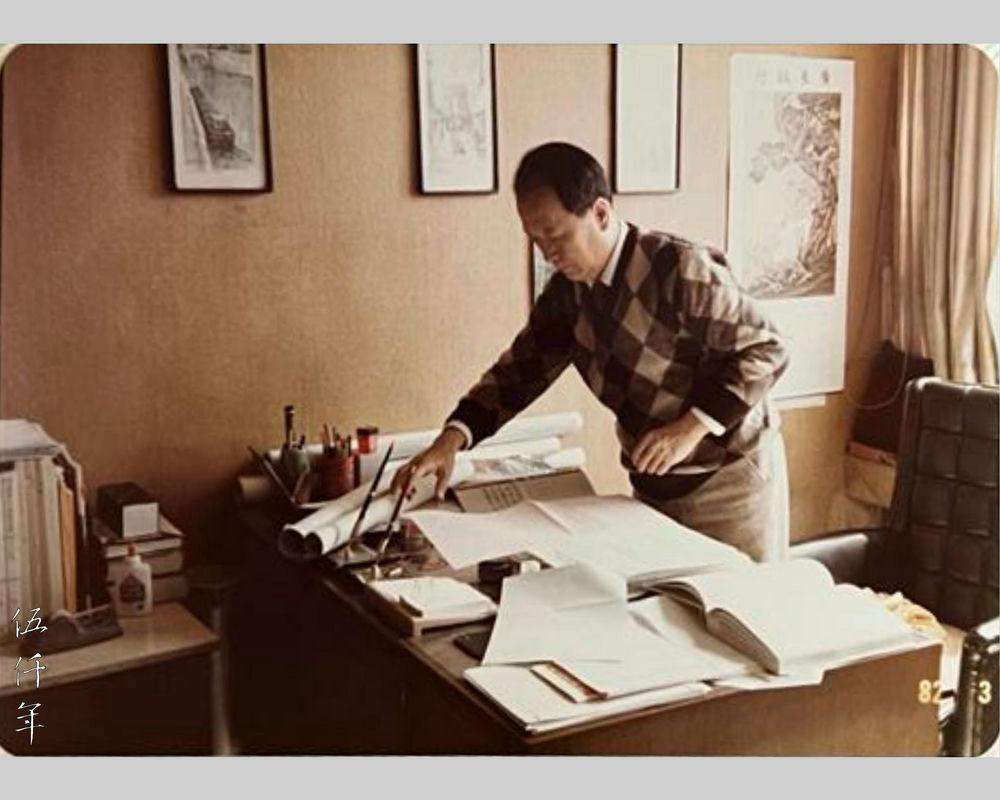

Portrait of Mr. Yang Cho-cheng in his office

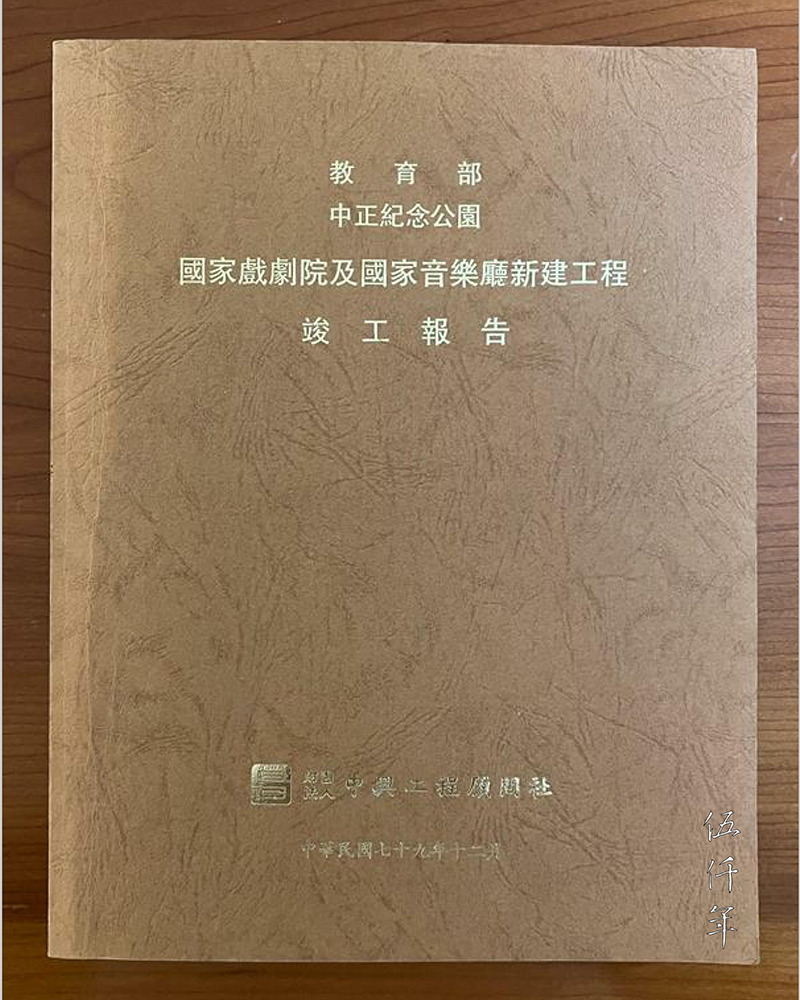

Front cover of the Completion Report of the National Chiang Kai-Shek Cultural Centre: National Theatre and Concert Hall, December 1990

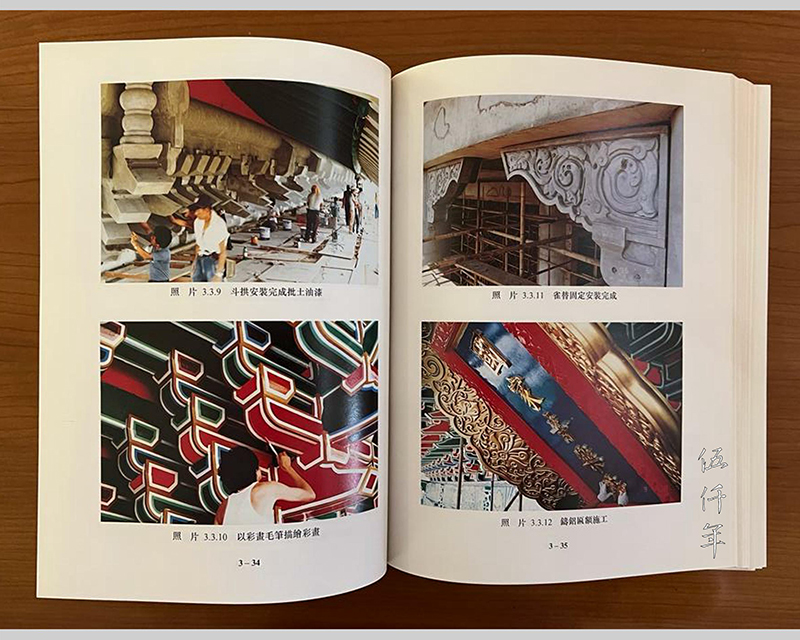

Inside page of the Completion Report of the National Chiang Kai-shek Cultural Centre: National Theatre and Concert Hall, December 1990

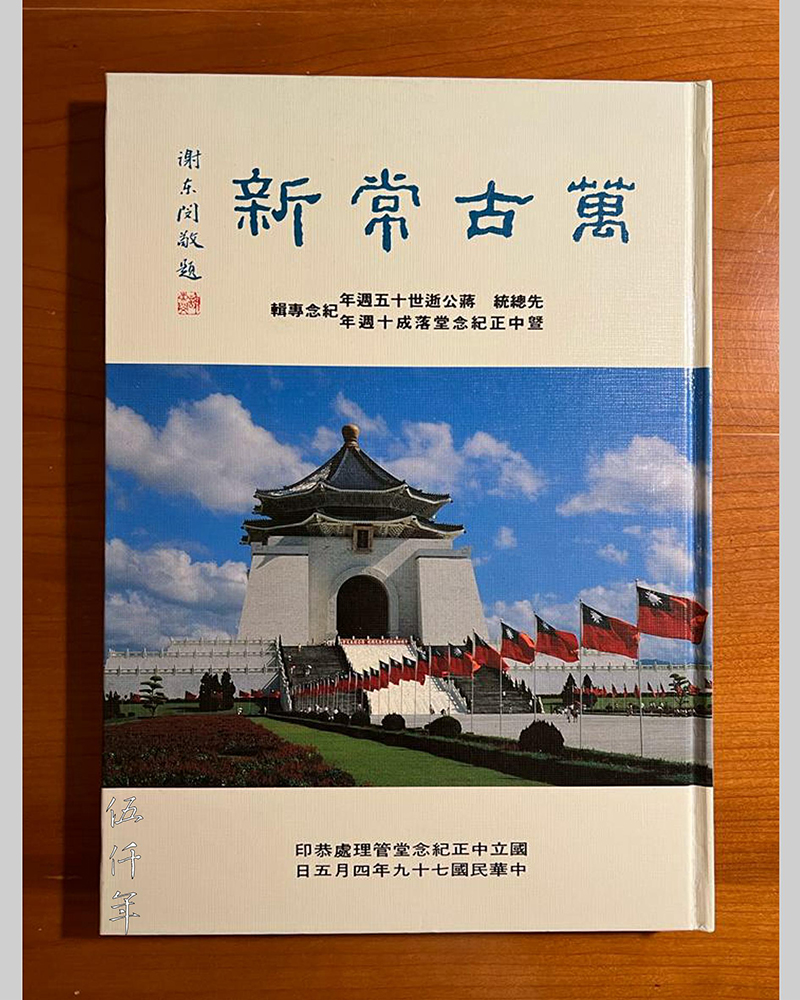

Front cover of the Special Issue to Commemorate the 15th Death Anniversary of President Chiang Kai-shek and the 10th Anniversary of the Completion of the President Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall

Inside page of the Special Issue to Commemorate the 15th Death Anniversary of President Chiang Kai-shek and the 10th Anniversary of the Completion of the President Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall

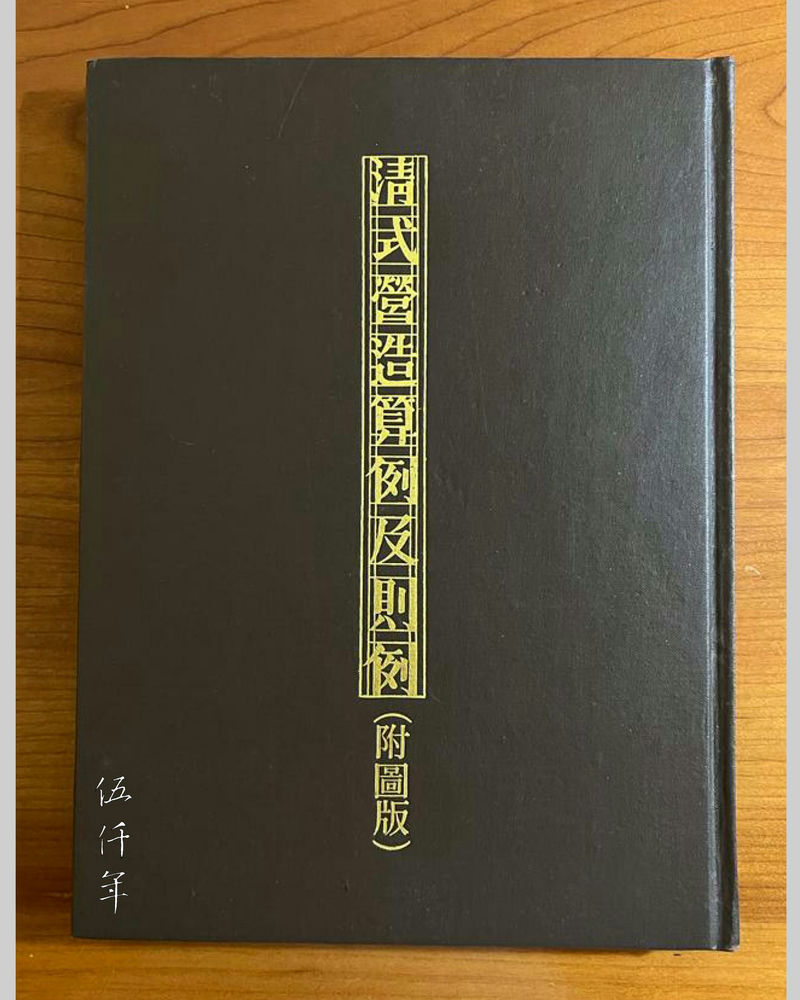

Front cover of The Calculations, Principles and Rules of Construction in the Ch’ing Dynasty

Inside page of The Calculations, Principles and Rules of Construction in the Ch’ing Dynasty

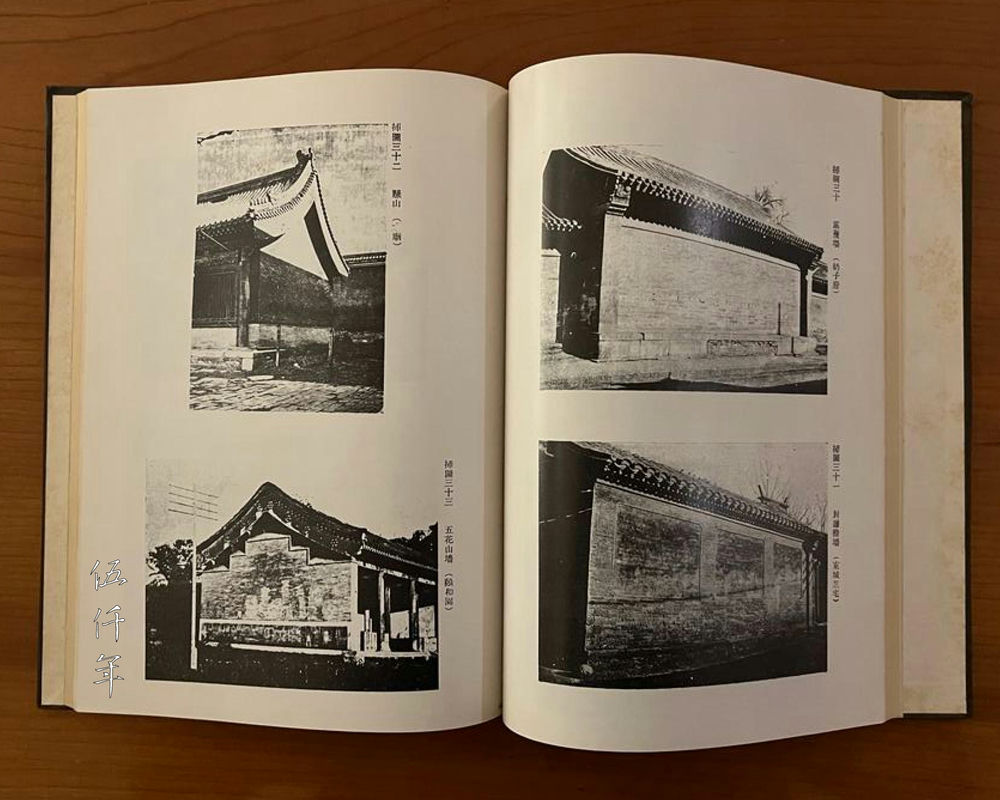

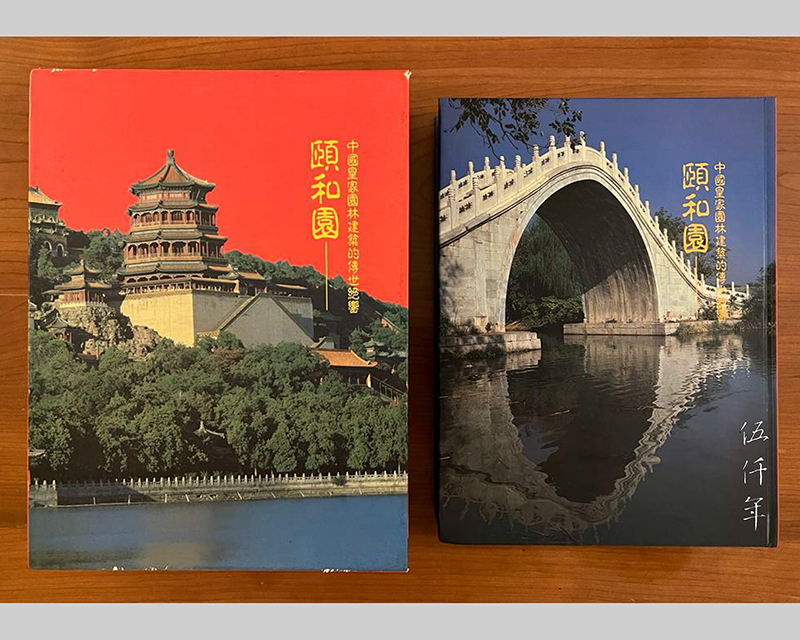

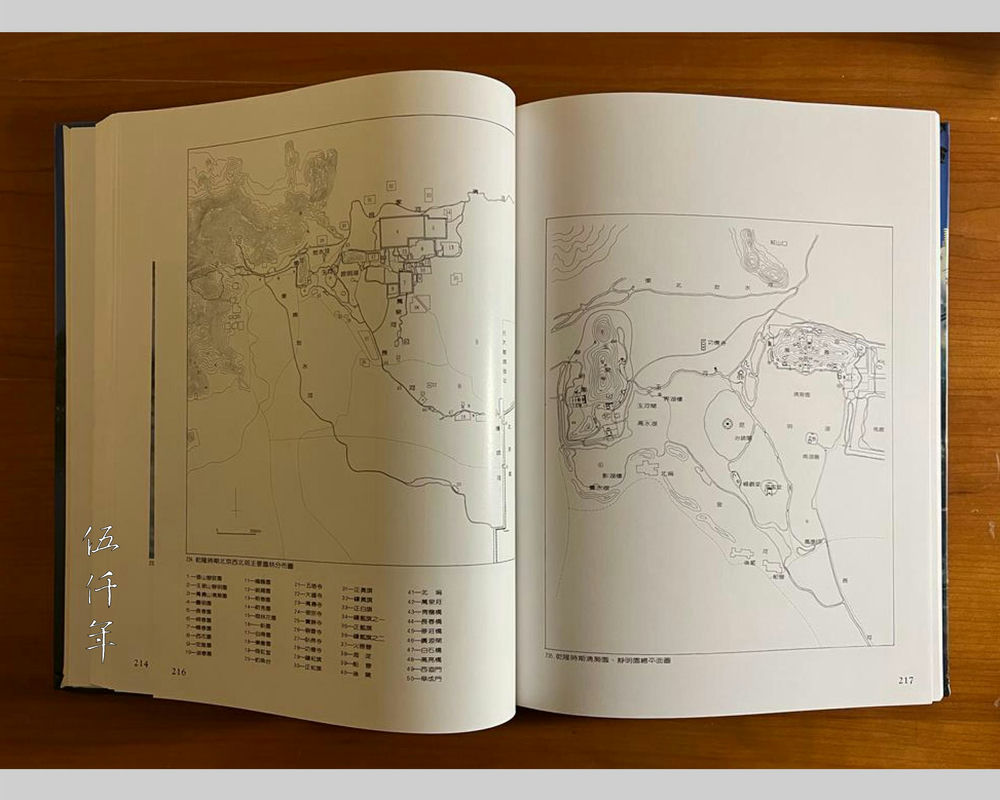

Front cover of The Summer Palace: A Closure to Chinese Imperial Garden Architecture

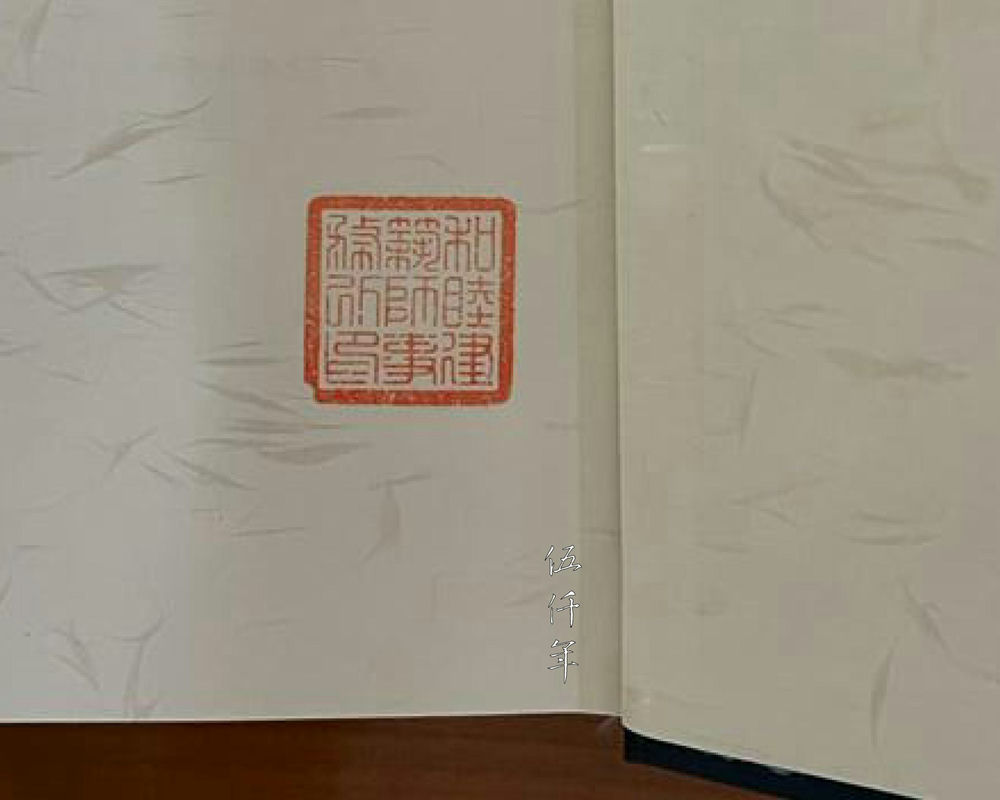

Inside page of The Summer Palace: A Closure to Chinese Imperial Garden Architecture

Seal of Ho-mu Architects Office impressed on the inside page of The Summer Palace: A Closure to Chinese Imperial Garden Architecture

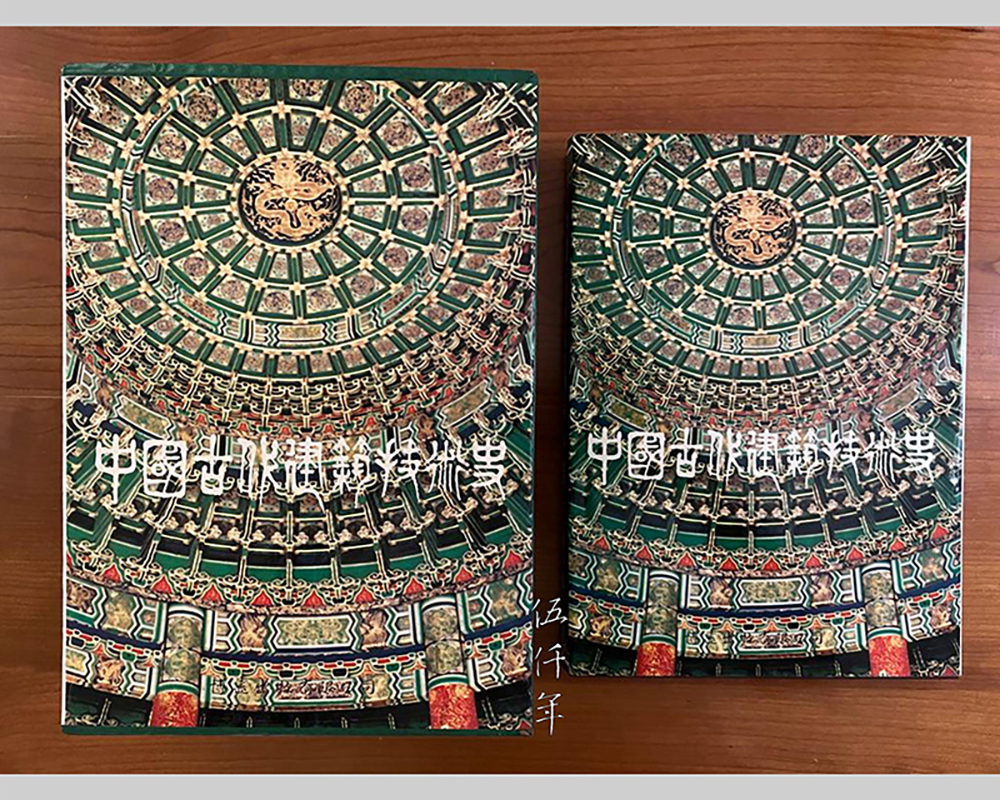

Front cover of History of the Building Technology of Ancient Chinese Architecture

Inside page of History of the Building Technology of Ancient Chinese Architecture

Front cover of Photograph Album of Ancient Chinese Architecture

Inside page of Photograph Album of Ancient Chinese Architecture

Inside page of Photograph Album of Ancient Chinese Architecture

Inside page of Photograph Album of Ancient Chinese Architecture

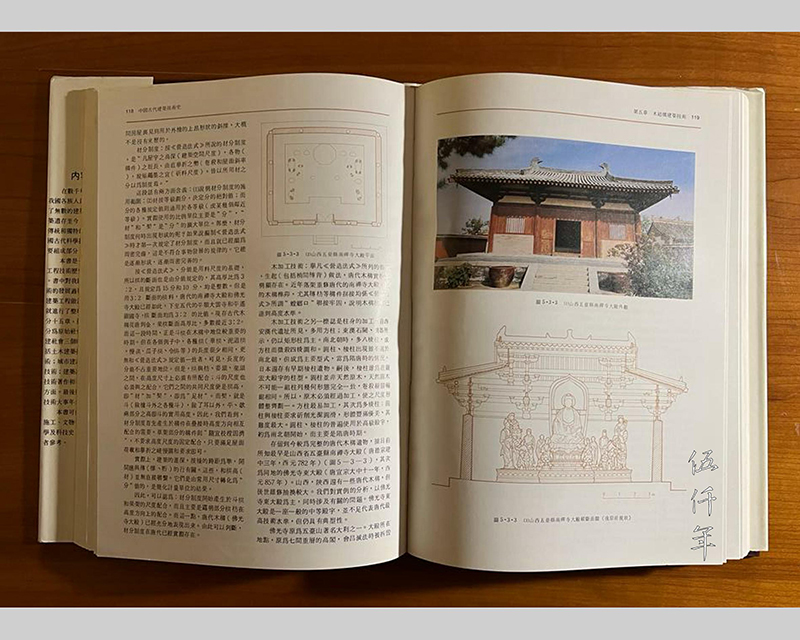

Front cover of Pictorial Record of the Restoration of Mountains and Rivers

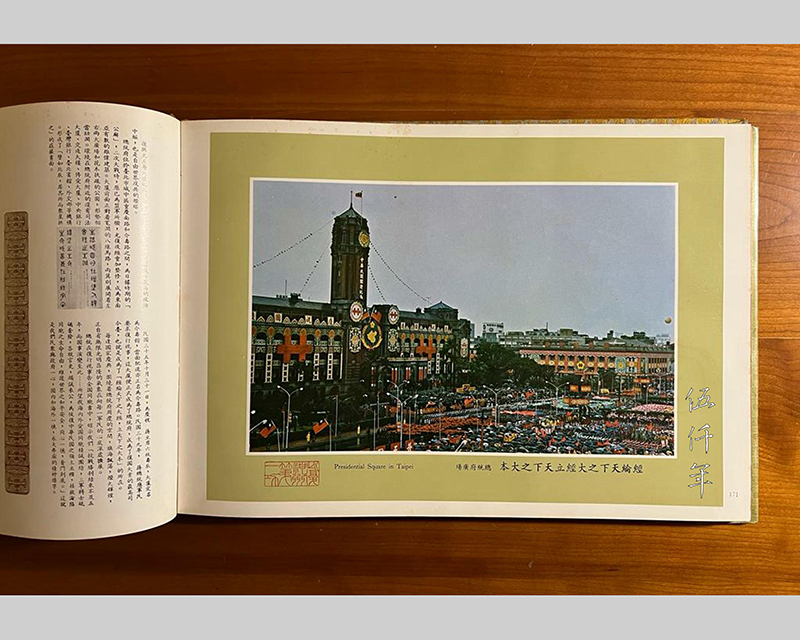

Inside page of Pictorial Record of the Restoration of Mountains and Rivers

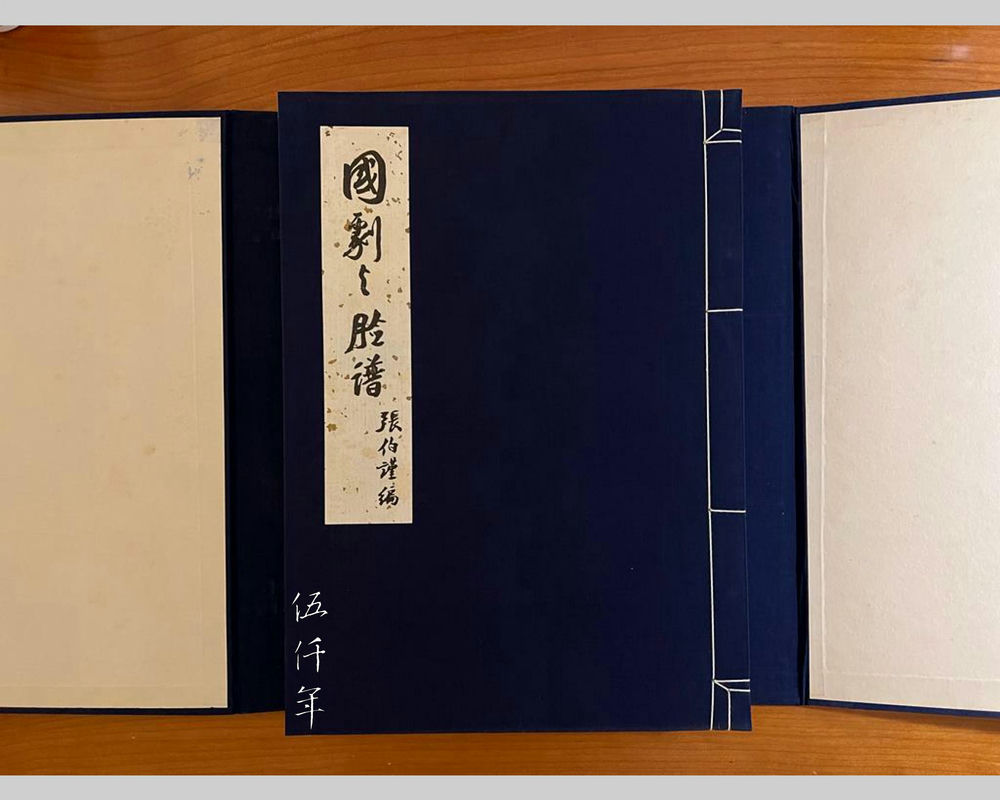

Front cover of Facial Makeups of Peking Opera

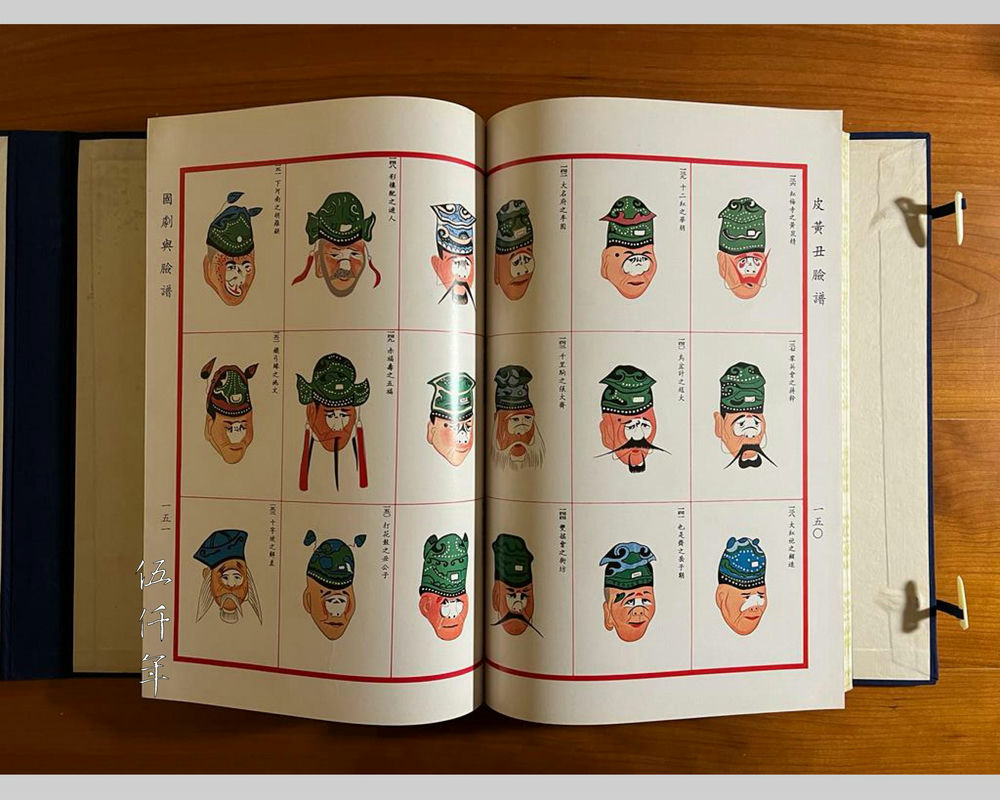

Inside page of Facial Makeups of Peking Opera

Related Contents:

Mr. Yang Cho-cheng (楊卓成先生), Master of Chinese Classical Architecture