The convention of collecting meditation stones has thrived since ancient times. The emperor Sung Hui-tsung (宋徽宗 1083-1135) was a stone aficionados too. His story of moving large unusual rocks by hua-shih kang (花石綱) vessels was told in the novel Shui-hu ch’uan (水滸傳 All Men are Brothers). Men of letters since then who are partial to meditative stones are simply innumerable. The lawyer Mr. Lin Shu-wei (林書緯) in our time is a gentleman who adores antiquity and for many years seeks gratification in meditation stones. He hereby displays a Ling-pi-shih stone and a Yin-shih stone in his collection for our pleasure. In the midst of an intense summer, in the throes of national commotion, gazing at a meditation stone by the window in silence can perhaps slightly relieve the disquiet.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

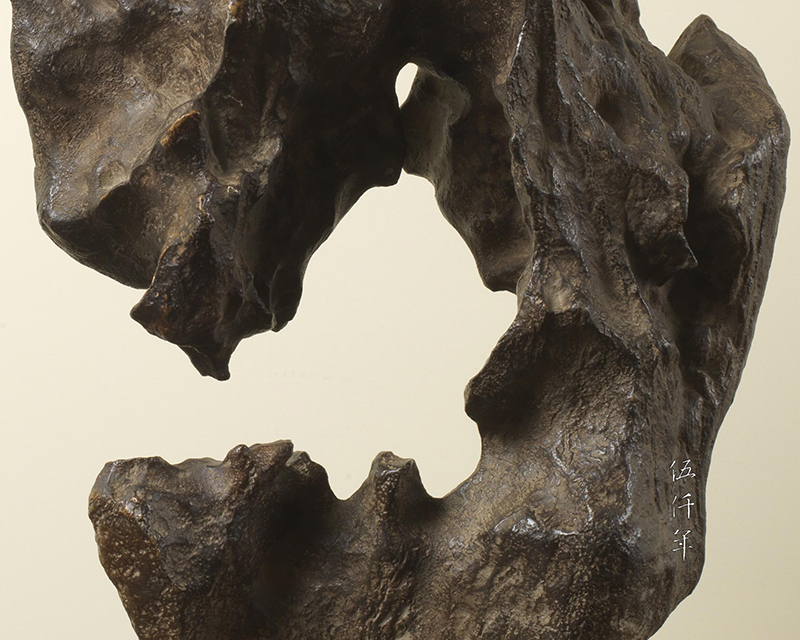

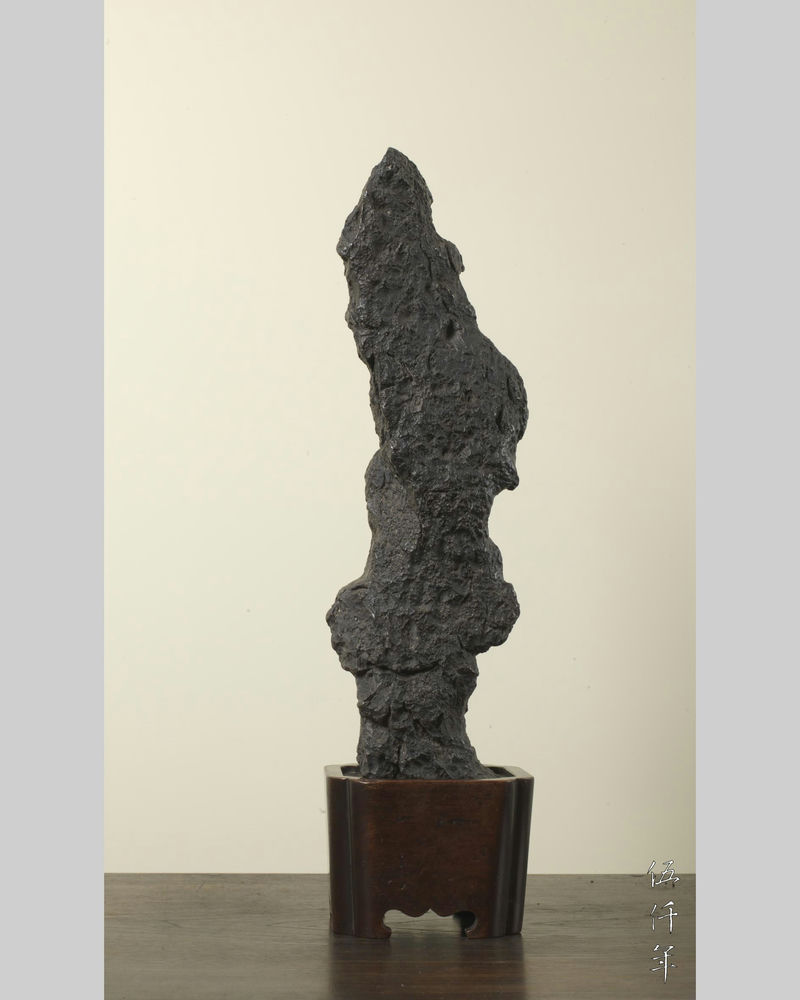

Detail of a Ling-pi-shih stone

“When does this sentiment begin, flowing to such depth?” This is likely an apt description of my personal feeling after years of involvement with ancient Chinese artefacts. For ancient artefacts, there is always an inexplicable warmth that surfaces from my heart. Friends often playfully comment that there is an old soul residing in my body. Whenever there is an ancient artefact, I become enamoured and bewitched.

I remember the external teaching class in my primary school, through which I first visited the National Palace Museum in Taipei. There I saw the Stone in Pork Form. By the time the lady tour guide finished her elucidation, I was fascinated. How could it be possible for a natural stone to resemble a piece of fat, tender and palatable pork? Now that I have made some in depth inquiries, I realize this is a piece of natural agate. During the process of geological evolution, the stone was affected by adjacent minerals, different coloured layers were formed. In the Ch’ing dynasty, this stone was spotted by a skilled craftsman, who processed the surface of the stone by the fine artistries of sawing, polishing and colouring. Finally a highly realistic and sculptural Stone in Pork Form was created, with clear definitions of the layers of skin, meat and fat. It looks like the famous Hangchou dish of Tung-p’o Pork, braised in soy sauce and melts in the mouth. The Stone in Pork Form has consistently won admirers from museum visitors. (Illustrations 1, 2, 3)

Illustration 1: Frontal view of Stone in Pork Form. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

Illustration 2: Detail 1 of Stone in Pork Form. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

Illustration 3: Detail 2 of Stone in Pork Form. Photograph courtesy National Palace Museum

Perhaps this juvenile encounter with the Stone in Pork Form made a lasting impression. Years later, I became a university student. One day when I was studying in the library, I saw a set of The National Palace Museum Monthly of Chinese Art. Leafing through the magazine, childhood memories reappeared. I was impelled to dash to the National Palace Museum to investigate, little did I know that this was the awakening of my dormant old soul. There was no turning back. In my leisure time, I would linger in museums and antique shops. To this day I have not worn out my interest, and the pleasure within such realm can only be truly appreciated by those who have shared this path.

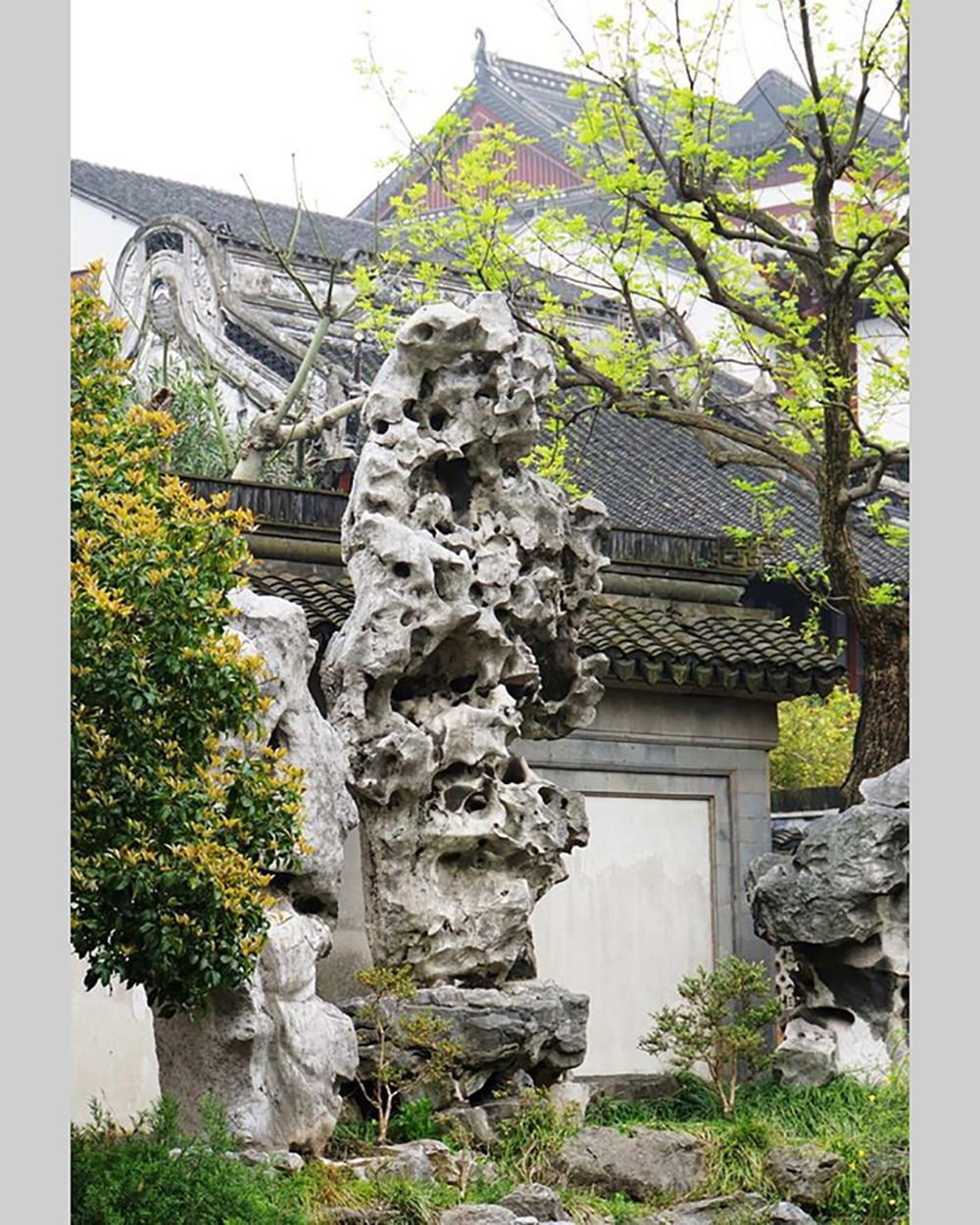

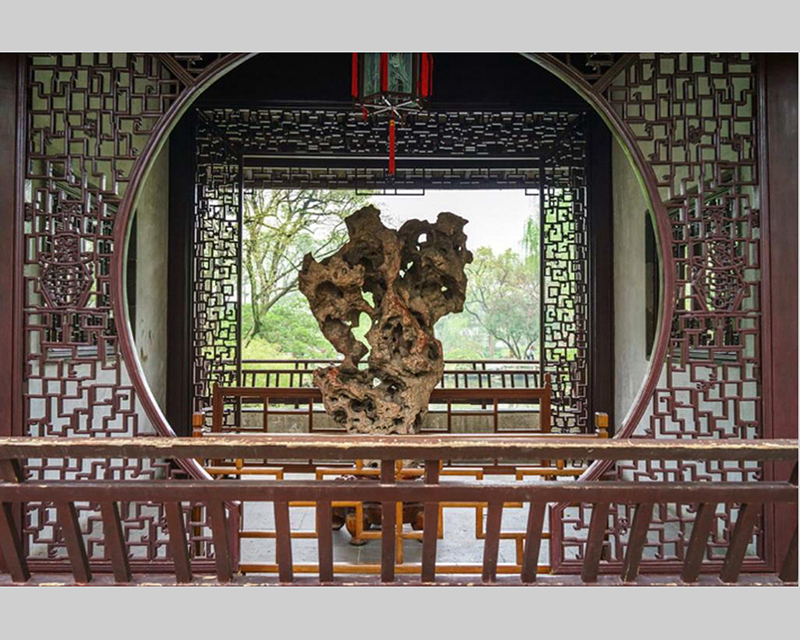

Chinese have a particular fondness for jade and stone. The fashion of stone appreciation started in the T’ang and the Sung Dynasties. It became fully developed by late Ming, and was widely popular after mid Ch’ing. Yet what contrived the culture of stone appreciation? First of all, ancient Chinese had always nurtured an unfathomable complex towards nature, especially so for the literati who not only yearned for mountains and rivers, they even instilled into them lofty moral sentiments. Whenever ancient Chinese encountered social unrests or personal setbacks, they resorted to the desire for country life, away from the trials and tribulations of life. Beside expressing their fervour for nature through paintings, they began to appreciate meditation stones on a smaller scale, advocating the aesthetic merits of form, silhouette, texture, material, colour and sound. These criteria articulated the spiritual affinity for nature among the literati. Since meditation stones encompass both painterly and sculptural dimensions, their appreciation gradually evolved from realism to abstraction, becoming a unique art form. meditation stones are eventually displayed on tailor-made stands or trays, sometimes in the interior of houses, sometimes in gardens. (Illustrations 4, 5, 6). They form dialogues with the spaces and environments they are displayed in, fulfilling the literati aspiration of the union between man and nature.

Illustration 4: Kuan-yün-feng stone from the Sung dynasty in Liu Yüan Garden in Soochow

Illustration 5: Yü-ling-lung stone from the Sung dynasty in Yü-Yüan Garden in Shanghai

Illustration 6: A meditation stone inside Fu-jung Hsüan in Zhuo-cheng Yüan Garden in Soochow

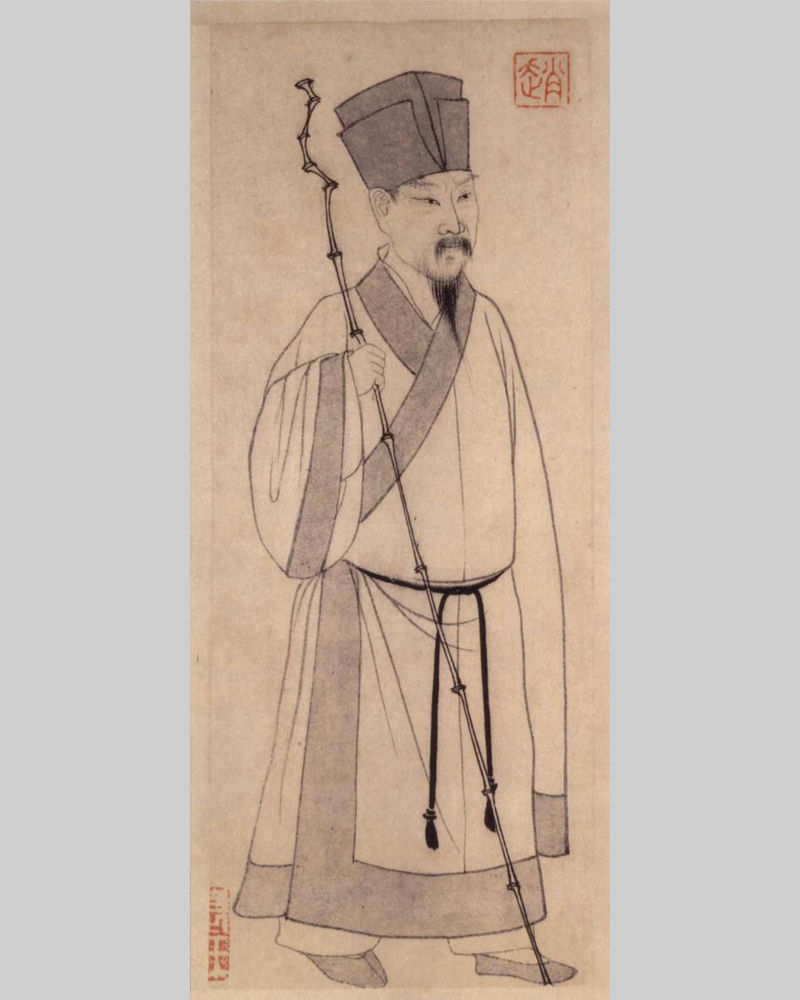

The aesthetics of the ancient literati are fully demonstrated by meditation stones. Although aesthetic preferences vary from person to person, the pursuits of the unusual and strange have been commonplace for millenniums. Some notable stone aficionados who favour the unusual and strange are the Sung literati Su Shih (蘇軾 1037-1101) and Mi Fei (米芾 1051-1107). (Illustrations 7, 8).

Illustration 7: Portrait of Su Shih (蘇軾)

Illustration 8: Portrait of Mi Fei (米芾)

On the surface, these literati were in pursuit of the unusual and strange, yet concealed behind this facade were their ideas of unworldliness, abandonment of convention, an instinctive and natural approach. They used meditation stones to investigate the intricate philosophies of realism and abstraction, form and void, balance and equilibrium. The fashion for unusual and strange stones among the Sung literati inspired a set of aesthetic rules: “Thinness, Wrinkling, Perforations, Openness.” To interpret these rules in contemporary language, they can be defined as: “The form is multi-faceted, the spirit is ethereal, the material is exquisite, the texture is congruous.” Through the many different arrangements of meditation stones on tables and in gardens, the stone aficionados can proactively extend and project their emotions onto the stones. There is an old saying: “The stone does not speak and it is most attractive.” This line suggests a reservoir of emotions from the beholder. For these reasons, meditation stones have become an art form that has outlasted a thousand years without diminishment.

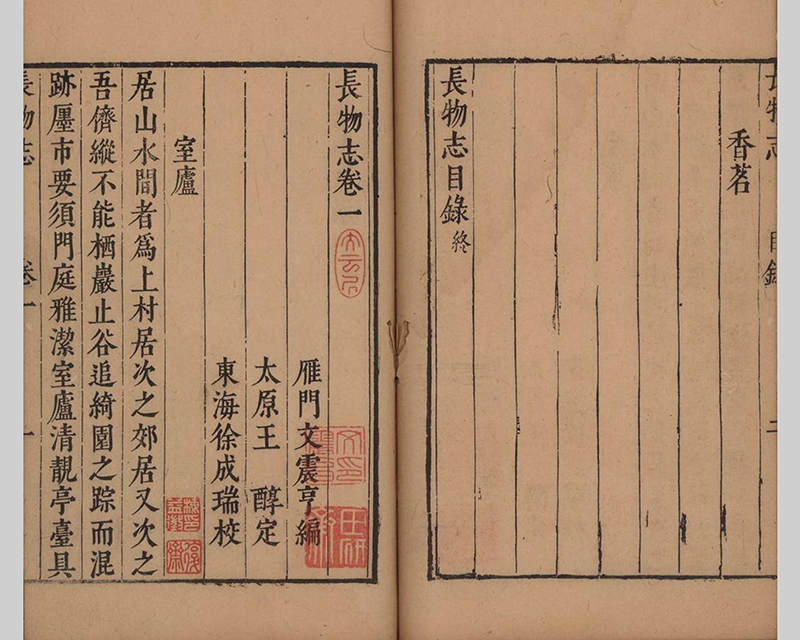

Illustration 9: Ch’ang-wu chih (長物志) by Wen Chen-heng (文震亨)

In Ch’ang-wu chih (長物志 Illustration 9) written by Wen Chen-heng (文震亨 1585-1645) of the Ming dynasty, he described meditation stones in this manner:

“The finest type of stone is Ling-pi-shih stone (靈璧), the second finest is Yin-shih stone (英石). These two types are very expensive and difficult to acquire. The large ones are particularly hard to find, the ones taller than a few feet are rarities, and the small ones can be placed on tables. Those with the colour of lacquer, sound resembling jade when struck, are the choicest. For horizontal stones, those with flat bases, vertical peaks and steep ridges are the best.”

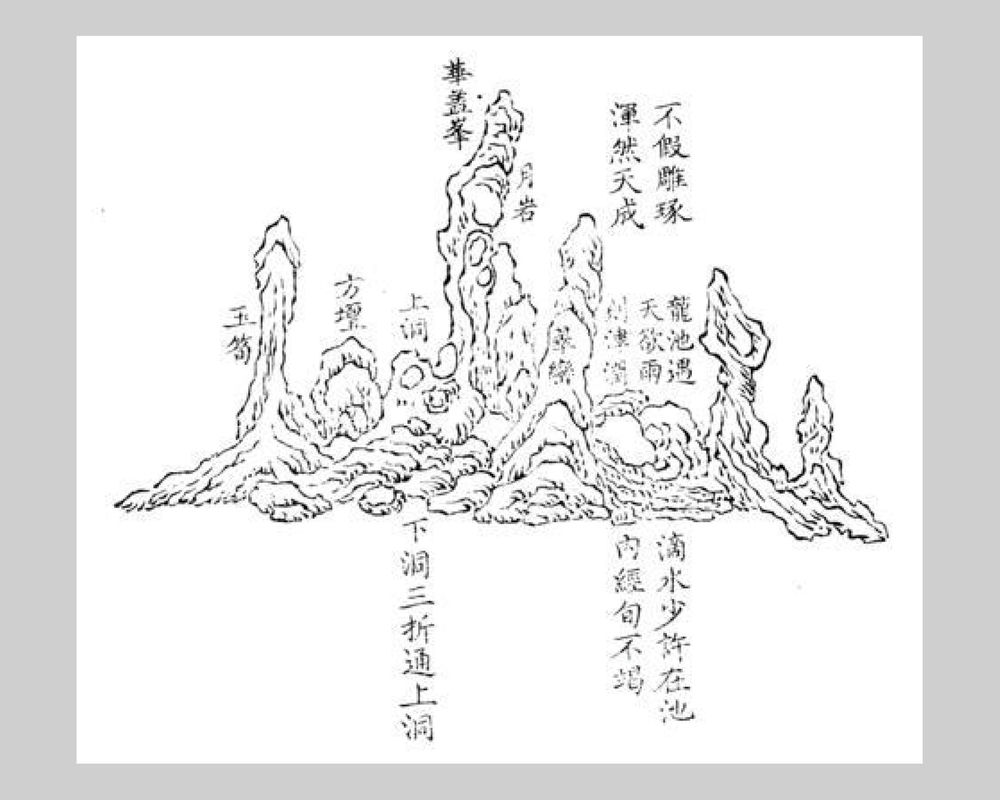

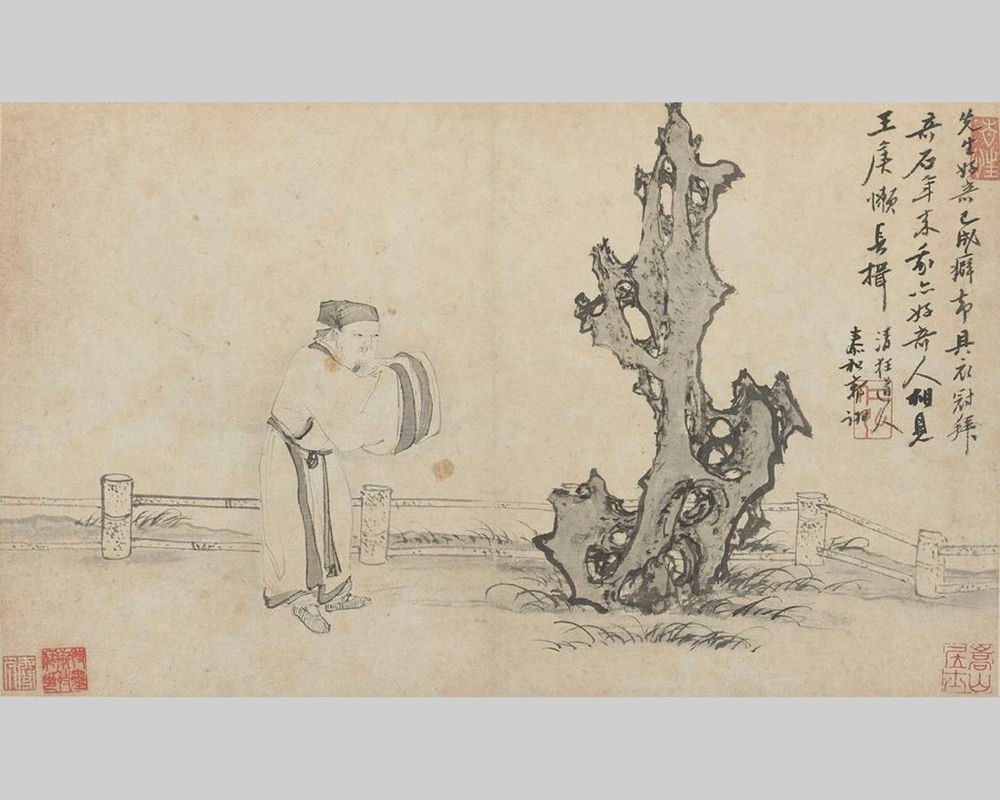

In late Ming society, there was an abundance of talented people, and many schools of thoughts. At that time, the two favourite forms of meditation stones were: the horizontal form of mountain range (Illustration 10), and the cloud top form (Illustration 11). The former had flat base, and easy to display, the latter must tailor-make a wooden stand to place it upright. Beginning from the Wan-li reign in the Ming dynasty, wooden stands for meditation stones became popular, the unity of stand and stone added another visual dimension for consideration. The styles of stone and stand are closely related to the fashion of the times. The style during late Ming and early Ch’ing is a continuation of that of the Sung dynasty: natural, simple and rustic. As fashion moved on, after mid Ch’ing, the style shifted further away from literati values and became affected, elaborate and mannered. By late Ch’ing, there was more emphasis on perforations and craftsmanship, losing its overall equilibrium, and fell into the vulgar trap of “pursuing meditation stones for the sake of meditation stones.” In this case, meditation stones have left their proper path, they no longer possess the vigor of the literati spirit, and few of the period specimens are worthy of connoisseurship.

Illustration 10: Stone of horizontal formation resembling a mountain range

Illustration 11: Painting of Mi Fei Bowing to a Stone by Kuo Hsü of the Ming dynasty

Since ancient times, there has been general consensus regarding the four great meditation stones for the garden. They are: Ling-pi-shih stone (靈璧石), Yin-shih stone (英石), T’ai-hu-shih stone (太湖石) and K’un-shih stone (昆石, some prefer Huang-la-shih stone 黃臘石). As Wen Chen-heng pointed out, Ling-pi-shih stone and Yin-shih stone enjoyed wide popularity among stone aficionados. The quarries of Ling-pi-shih stone are located in Ling-pi county of Anhui province. Its excavation can be traced far back to the T’ang dynasty. The stone is robust and hard, the texture craggy and rugged, when it is knocked upon, the sound clangs and clatters, the surface is gully, the pattern staggered and covered by crumples. The common colors are black, grey and pale brown, occasionally they come in greenish-blue, white and brownish-yellow. The forms and colours greatly vary, they appear in infinite shapes, the peaks and ranges ebb and flow, they are highly attractive for gazing and enjoyment, and fit the traditional criteria applied to stone appreciation. Literati from past generations cherished them, collected them, and regarded them as the foremost meditation stone.

The quarries of Yin-shih stone are located in Yin-te county of Kwangtung province. There are two categories of Yin-shih stone, Yang-shih stone and Yin-shih stone. Yang-shih stone is exposed above the ground, after years of weathering, the forms are thin and steep, the surface has many crinkles, the stone is hard, when it is knocked upon, the sound is brittle. Yin-shih stone is buried under ground, the forms are perforated and imposing, the material is sleek and smooth, when it is knocked upon, the sound is faint. The most common colour of Yin-shih stone is greyish-greenish-blue, occasionally there are white veins. The finest is of lacquer black colour, when it is knocked upon, the sound is metallic, the material is smooth. In Ch’ang-wu chih, Wen Chen-heng commented:

“Yin-shih is from Yin county, it is found upside down under the crags, these stalactites are procured by saw, hence the base is flat, the shape resembles a peak, some are three feet long, and some only over an inch. In front of the study, one can stack a little hill, it is rare and unworldly, but the geographic distance is too far to acquire.”

The distinguished gardener Chi ch’eng (計成 1582-1642) of the Ming dynasty wrote a treatise Yüan-yeh (園冶), he also mentioned Yin-shih stone:

“The large ones can be placed in the garden, the small ones can be placed on the tables. It can be used to decorate a tray, or a little vista.”

We can see that they are most suitable for gazing and enjoyment. Literati from past generations not only treasured them, they frequently composed poetry in their praise. Stone aficionados recollect these literary stories and celebrate them.

Once I had a conversation with an old collector. He shared his years of experience in collecting meditation stones. He advised:

“It is better to collect classics and not influenced by fashion, it is better to have few and not too many common pieces, it is better to have plain pieces and not affected pieces.”

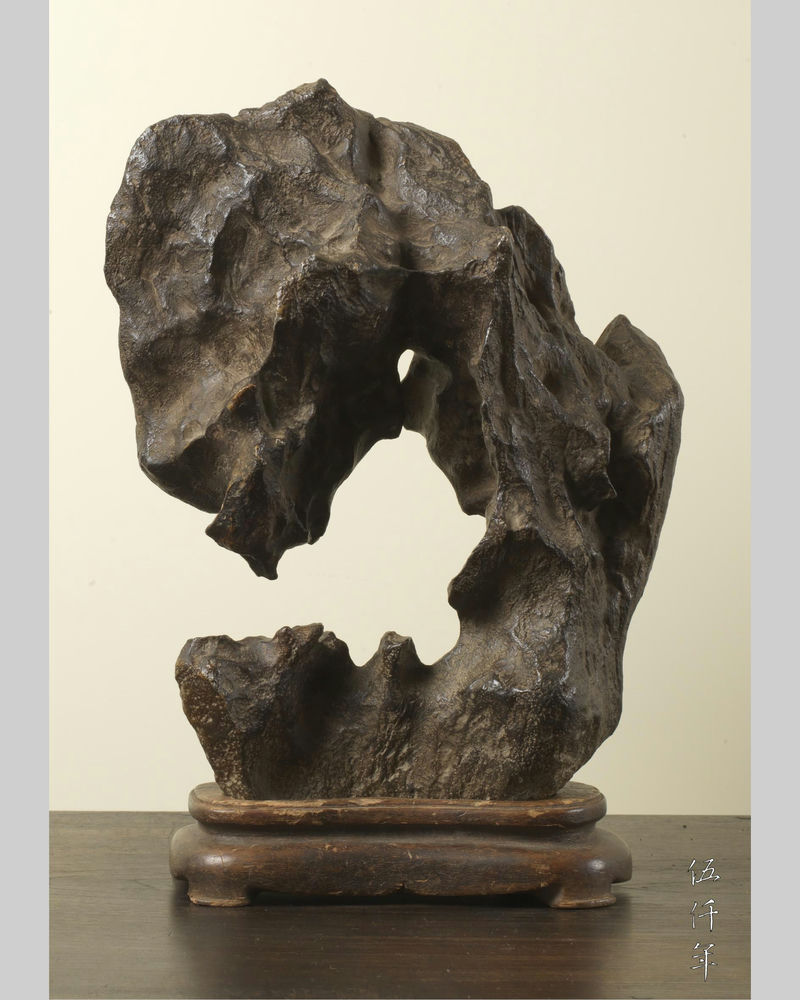

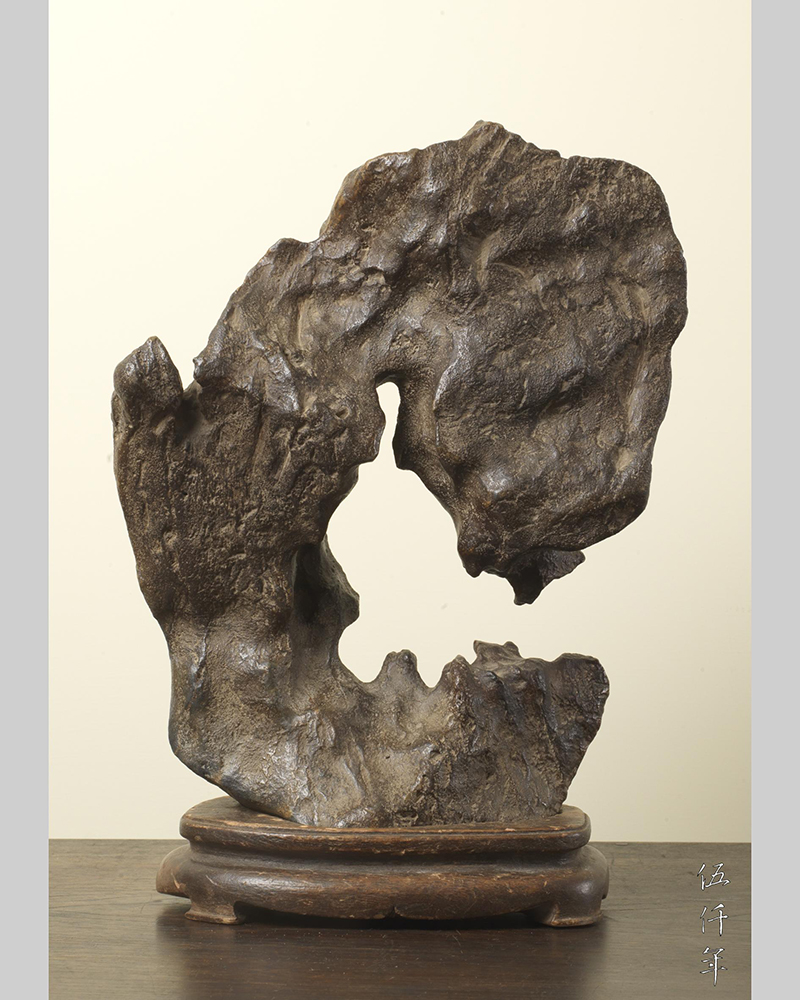

I kept these words of wisdom as rules for my own collecting. Years ago, I acquired a Ling-pi-shih stone from early Ch’ing. The form resembles a projecting cliff, the surface is craggy, the colour is greyish-black, the patina is ancient, and it is fitted with a phoebe zhennan wooden stand. The stone and the stand complement each other well. They are well proportioned, a perfect match. (Illustration 12, 13, 14,15). There is an old saying about Ling-pi-shih stone: “To find a stone natural and undamaged on all four sides, there are only one or two in a few hundred.” This illustrates the rarity of a perfect specimen, those finely crafted pieces of late Ch’ing are of no comparison. This is indeed a piece to be treasured. Examining this stone from different sides, they are all pleasing to the eyes. I have installed it in the foyer for constant pleasure.

Illustration 12: Frontal view of a Ling-pi-shih stone

Illustration 13: Detail of a Ling-pi-shih stone

Illustration 14: Back view of a Ling-pi-shih stone

Illustration 15: Detail of a Ling-pi-shih stone

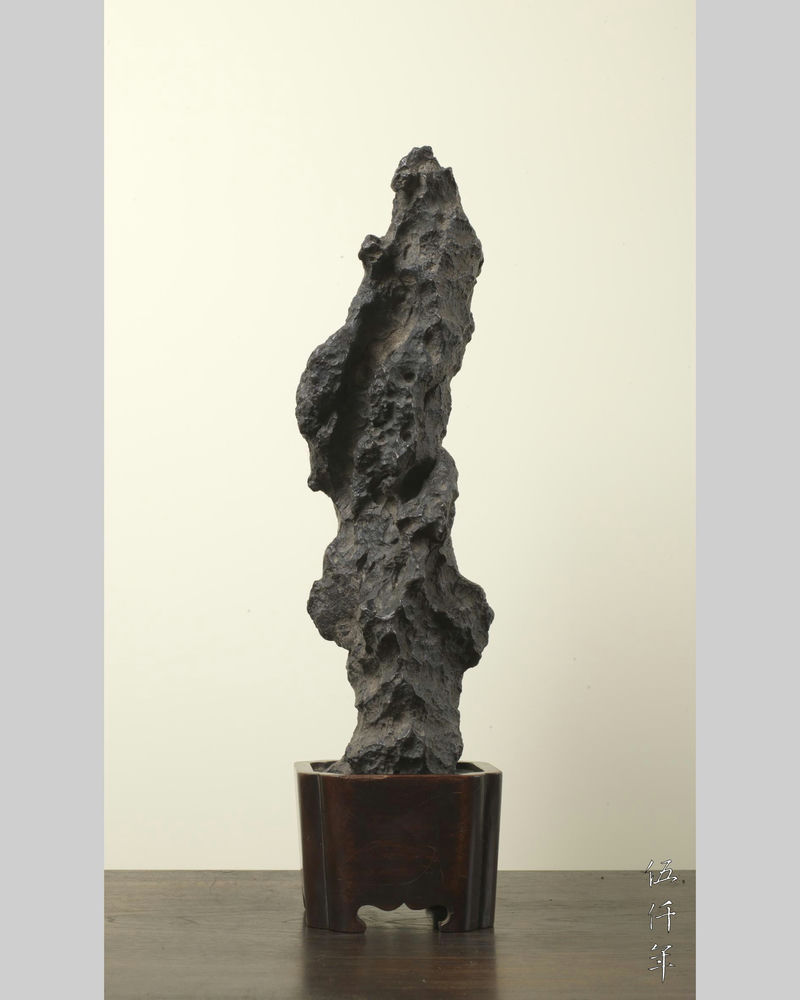

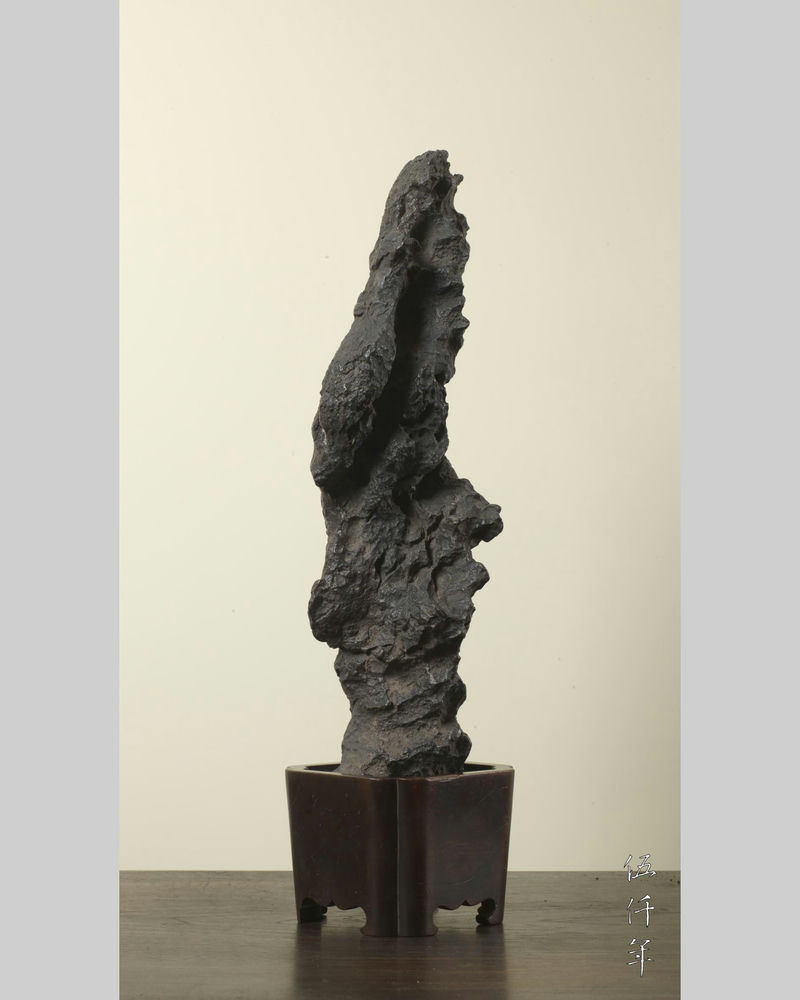

Some years later, there was another fortuitous moment. A friend acquired a Yin-shih stone from mid-Ch’ing. I was enthralled. I pursued it for a few months, and eventually convinced my friend to part with it. I was thrilled to receive it and could not keep my hands off it. It was like attaining a rare treasure. The form of this Yin-shih stone resembles a lonely peak, a steep rise, like a man standing. The surface is totally rugged, the colour blackish, it has the virtues of thinness, wrinkledness, agileness and elegance. The original tailor-made rosewood stand was crafted according to the inserted shape of the stone, its form and proportion complemented well the shape of the stone. It was carefully thought out, the material was fine, and the craftsmanship excellent. (Illustrations 16, 17, 18, 19. 20). I display this stone on my desk, enhancing the literary ambience of the room.

My emotions towards ancient artefacts, consist of not just fondness, but cherishment and admiration. It is plain that a fortuitous possession can only be a temporal custodianship. This article aspires to share my personal pleasure with like-minded people. I hope more people will appreciate the aesthetics of the ancient literati and the cultural contents of the meditation stones, so that this heritage can continue.

Illustration 16: Frontal view of a Yin-shih stone

Illustration 17: Side view of a Yin-shih stone

Illustration 18: Back view of a Yin-shih stone

Illustration 19: Detail of a Yin-shih stone

Illustration 20: Detail of a Yin-shih stone