Madame Chiang Kai-shek passed away on 23 October in the 92nd year of the Republic (2003). It is now promptly twenty years since her death and commotions in our world have been without end. Recalling Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s address at the Commemoration of the Birth Centenary of President Chiang Kai-shek, which took place at the National Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall in the 75th year of the Republic (1986), one of her lines was: “Let the sons and daughters of the Chinese race follow the footsteps of our eminent forefathers, to complete this magnificent mission that Free China Shall Rise Again!” In this time of darkness, the phrase Free China Shall Rise Again is a reminder akin to morning gong and evening drum. We are delighted to offer an article by Mr. Ch’en Lun and Ms. Jocelin Chiang titled: The Longest Address by Madame Chiang Kai-shek during Her War-Time Visit to America, including the full text of the address and a rarely seen documentary film. We hope people everywhere will take heart to the notion that Free China Shall Rise Again.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

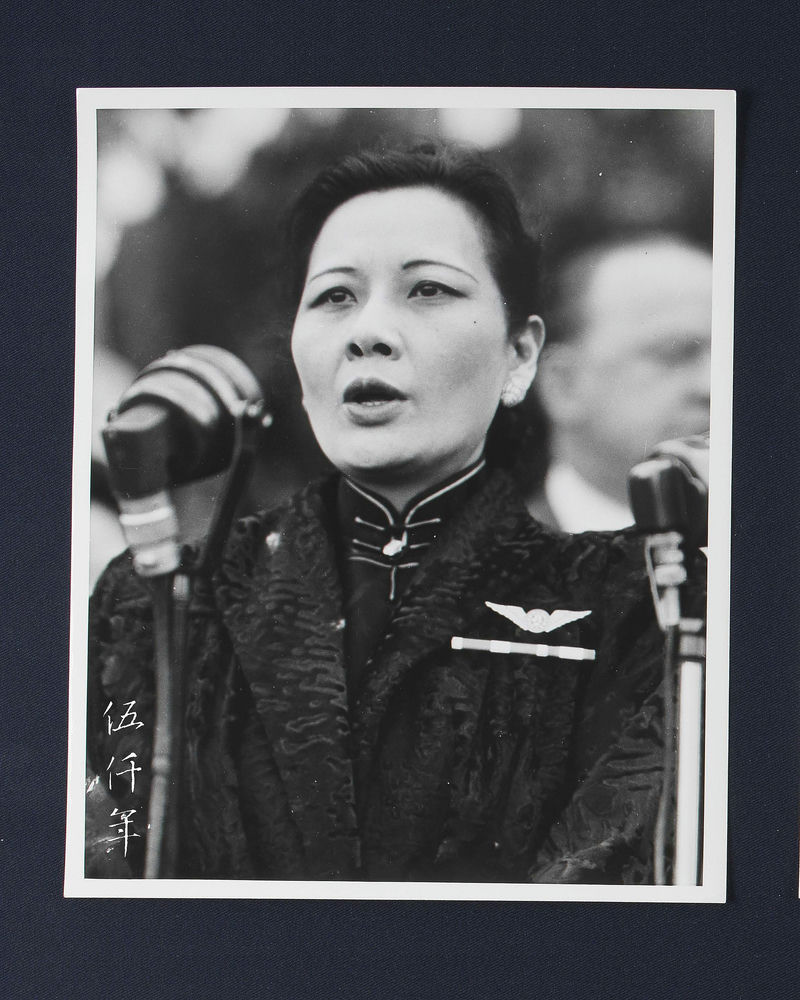

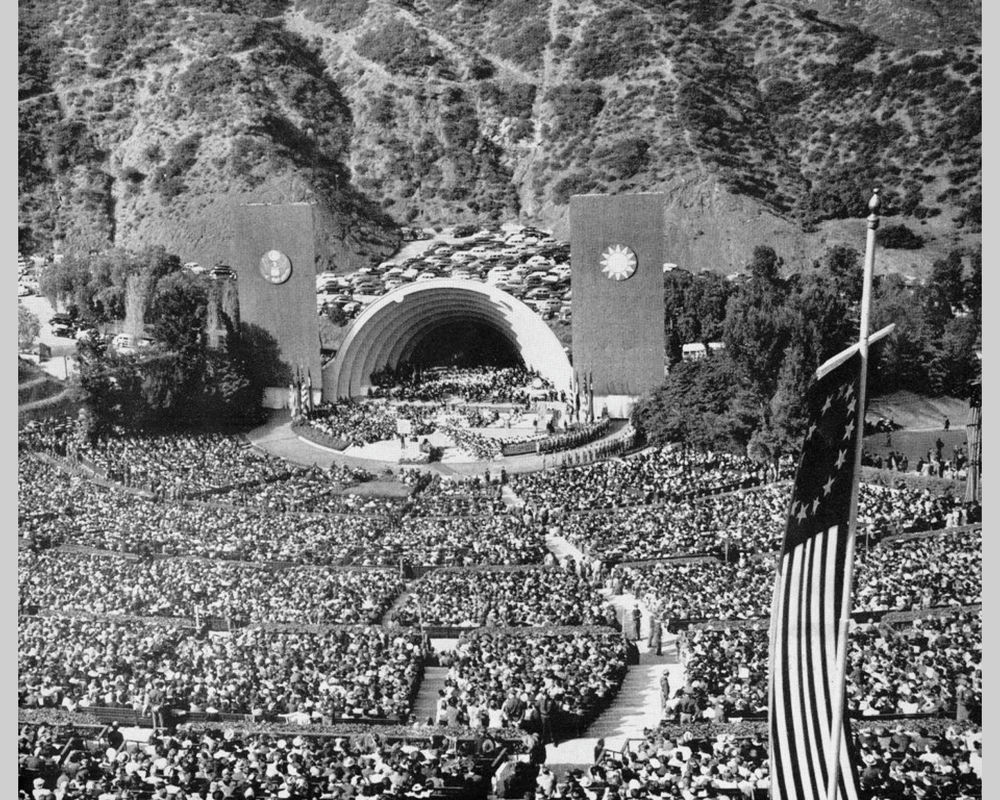

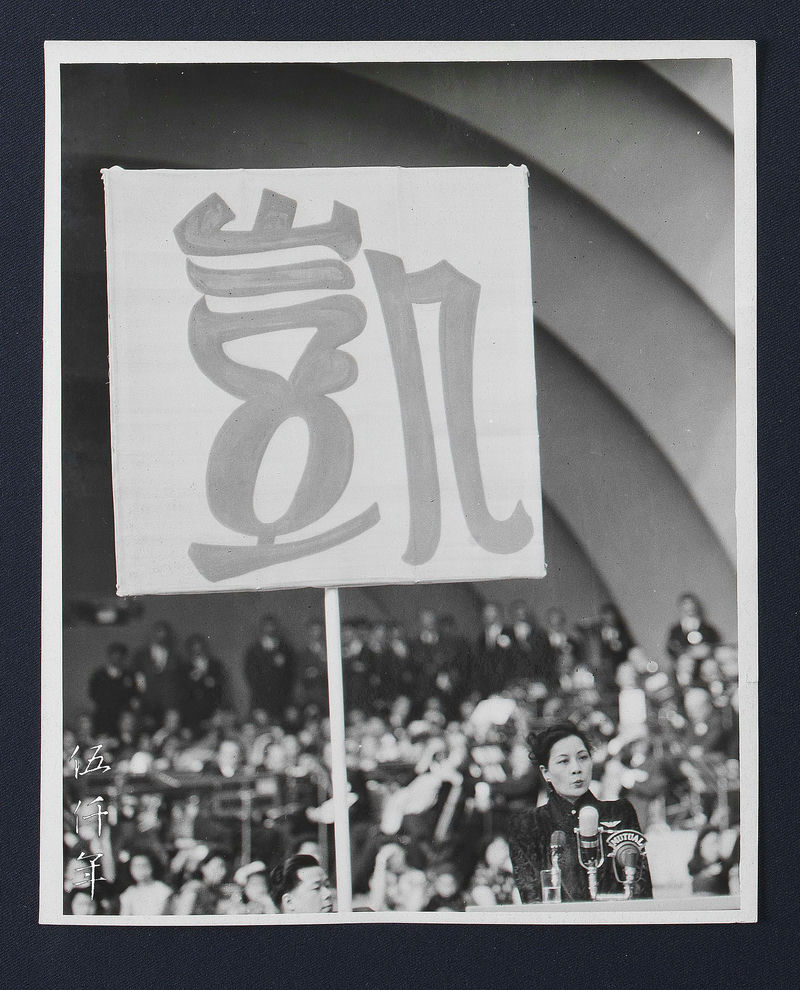

Madame Chiang Kai-shek addressing the audience at Hollywood Bowl on 4 April 1943. Photograph courtesy Mr. Roy Delbyck

Madame Chiang Soong Mei-ling (蔣宋美齡女士) was the wife of the late President Chiang Kai-shek. She devoted her entire life to supporting her husband at his side, leaving a lasting contribution to both the Nationalist Party and the Republic of China. Madame Chiang possessed deep knowledge of Western culture and language. This enabled her to enhance China’s reputation internationally by engaging with the political leaders of powerful countries and advocating for China’s interests. At the critical moment of the nation’s life and death struggle, she used her words to inspire and unite the will of the people and in addition, she initiated the establishment of China’s future air force, earning her the name “Mother of the Chinese Air Force”. In the turmoil of war, she demonstrated maternal love and care for orphaned and vulnerable children, becoming a role model for modern women. She led in advancing the status of women and changing societal attitudes towards women. As mainland China fell to the communists, she urged and appealed to both the government and the people of the United States to support Free China, connecting anti-communist and pro-Republic of China forces in the United States and influencing U.S. policy towards the Republic of China for nearly three decades. In summary, her life’s work can be encapsulated as the laying of the foundation for a free and democratic modern China. On the twentieth anniversary of Madame Chiang’s passing, with mainland China still under communist rule, the legacy of her conduct and moral principles more than ever can serve to inspire and guide future generations.

Madame Chiang Soong Mei-ling was born on 4 March 1898, in the 24th year of the Kuang-hsü reign. She passed away on 23 October 2003, in the 92nd year of the Republic of China. Her family was from Wen-ch’ang County (文昌縣), Kwangtung Province, but she was born in Shanghai. Her father, tzu Yao-ju (耀如), original name Chia-shu (嘉樹), was a Christian pastor and a revolutionary elder. She had older sisters Ai-ling (靄齡) and Ch’ing-ling (慶齡), older brother Tzu-wen (子文,also known as Tse-vung) and younger brothers Tzu-liang (子良) and Tzu-an (子安). In 1908, the 34th year of the Kuang-hsü reign, she moved to live in the United States at the age of eleven. In 1912, the 1st year of the Republic, she entered the Wesleyan College in Georgia. In 1913, the 2nd year of the Republic, she enrolled at Wellesley College in Massachusetts. In 1917, the 6th year of the Republic, she returned to China and in December 1927, the 16th year of the Republic, she married the late President Chiang Kai-shek.

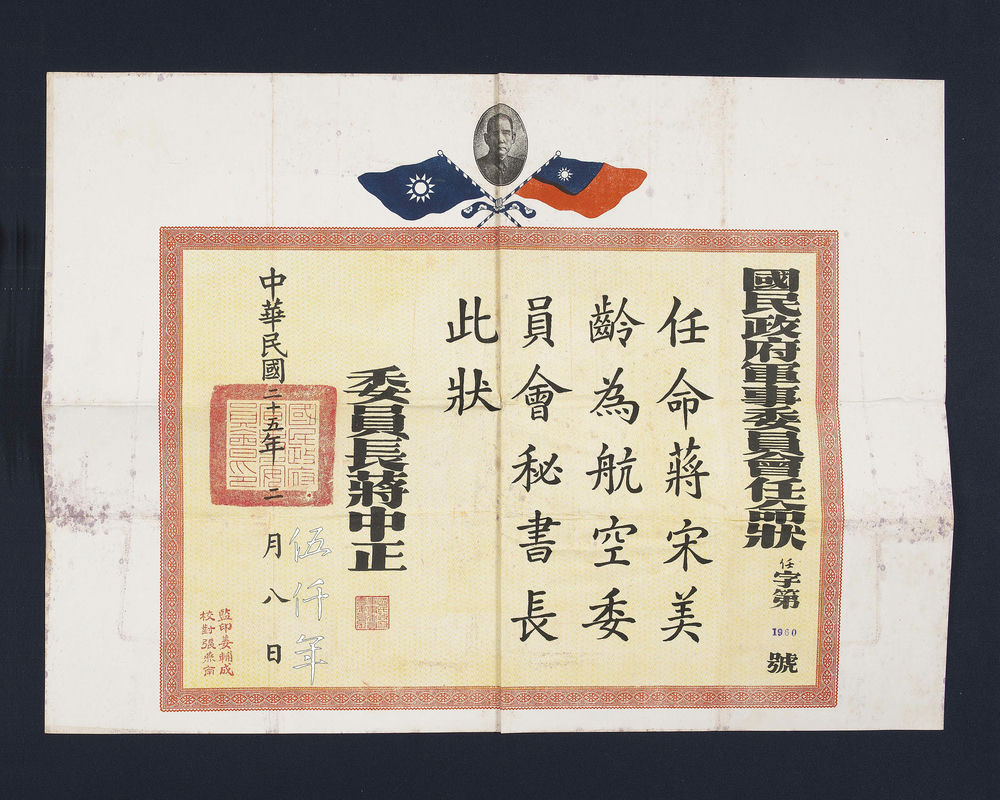

Appointment certificate from the National Government Military Council to Madame Chiang Kai-shek appointing her as the secretary-general of the Chinese Aviation Commission, dated 8 February 1936. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

In the spring of 1934, the 23rd year of the Republic, she assisted President Chiang in promoting the New Life Movement (新生活運動). In February 1936, the 25th year of the Republic, she was appointed secretary-general of the Chinese Aviation Commission (中國航空委員會秘書長). Thereafter, she became the chief-instructor of the Women’s Guidance Committee of the Association for the Advancement of New Life Movement (新生活運動促進總會婦女工作指導委員會指導長). On 12 December of the same year, when Chang Hsüeh-liang (張學良) abducted President Chiang during the Sian Incident, Madame Chiang’s skillful handling of the situation played a crucial role in resolving the crisis. On 7 July 1937, the 26th year of the Republic, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident erupted, marking the beginning of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression. In August the same year, Madame Chiang founded the Association of Chinese Women for Comforting Self-Defence Officers and Soldiers of the War Against Japanese Aggression (中國婦女慰勞自衛抗戰將士總會). In March the following year, she founded the Society for the Care of War-Time Children(戰時兒童保育會)under the Association of Chinese Women for Comforting Self-Defence Officers and Soldiers of the War Against Japanese Aggression.

In February 1942, the 31st year of the Republic, Mrs. Chiang and President Chiang visited India, her diplomatic talent was on show in this trip. In the same year, she was appointed honorary commander of the American Volunteer Group of the Republic of China Air Force (中華民國空軍美籍志願大隊榮譽司令). In November she went to the United States for medical treatment. In 1943, the 32nd year of the Republic, she accepted the invitation from President Roosevelt of the United States to address the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives on 18 February, affirming Sino-American friendship and China’s commitment to the war against Japan. Madame Chiang’s address to the U.S. Congress was a major diplomatic event for China; as for the United States, she was the first woman to address both houses of Congress. After leaving Washington, Madame Chiang visited New York, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. On 16 June she addressed the Canadian Parliament. In late June, she traveled through Washington, Boston, and New York, before returning in early July to the wartime capital Ch’ung-ch’ing (重慶). In November the same year, she accompanied President Chiang to the Cairo Conference. Besides carefully translating President Chiang’s intentions, she also participated in the capacity of secretary-general of the Chinese Aeronautics Commission and played an important advisory role. In recognition of her contribution, she was awarded the Order of Propitious Clouds, First Class (一等卿雲勳章) upon her return to China. In 1945, the 34th year of the Republic, she was appointed head of the Central Committee for Women’s Movement (中央婦女運動委員會主任).

Portrait of Madame Chiang Kai-shek taken in New York, March 1943. Photograph courtesy Mr. Roy Delbyck

In November 1948, the 37th year of the Republic, when the political and military situations on mainland China took a turn for the worse, Madame Chiang went to the United States to seek aid. Her mission failed. In January 1950, the 39th year of the Republic (1950), she arrived in Taipei and assumed the role of head of the Chinese Women’s Anti-Communist and Anti-Russian Federation (中華婦女反共抗俄聯合會主任委員), now known as the National Women's League of the R.O.C. (中華民國婦女聯合會), and founded the Hua Hsing Children’s Home (華興育幼院). In 1957, the 46th year of the Republic, she served as the head of the China Prevention of Tuberculosis Association (中國防癆協會主任委員). The following year, she became the honorary president of the China National Amateur Athletic Federation (中華全國體育協進會名譽會長). In 1967, the 56th year of the Republic, she was appointed honorary chairwoman of Fu Jen Catholic University (輔仁大學名譽董事長). After the government relocated to Taiwan, Madame Chiang utilized her diplomatic skills to maintain and strengthen ties with those American friends who supported Free China, using their best efforts to influence American policy towards the Republic of China. It is said that such American friends, also known as China Lobby, delayed for nearly thirty years the severance of diplomatic relations between the United States and the Republic of China, and for this, credit is due to the significant role of Madame Chiang.

President Chiang passed away on 5 April 1975, in the 64th year of the Republic. In September the same year, Madame Chiang moved to the United States. In 1981, the 70th year of the Republic, her sister, Soong Ching-ling, passed away on the mainland. The Chinese Communist Party extended an invitation for her to attend the funeral which was firmly declined by Madame Chiang.

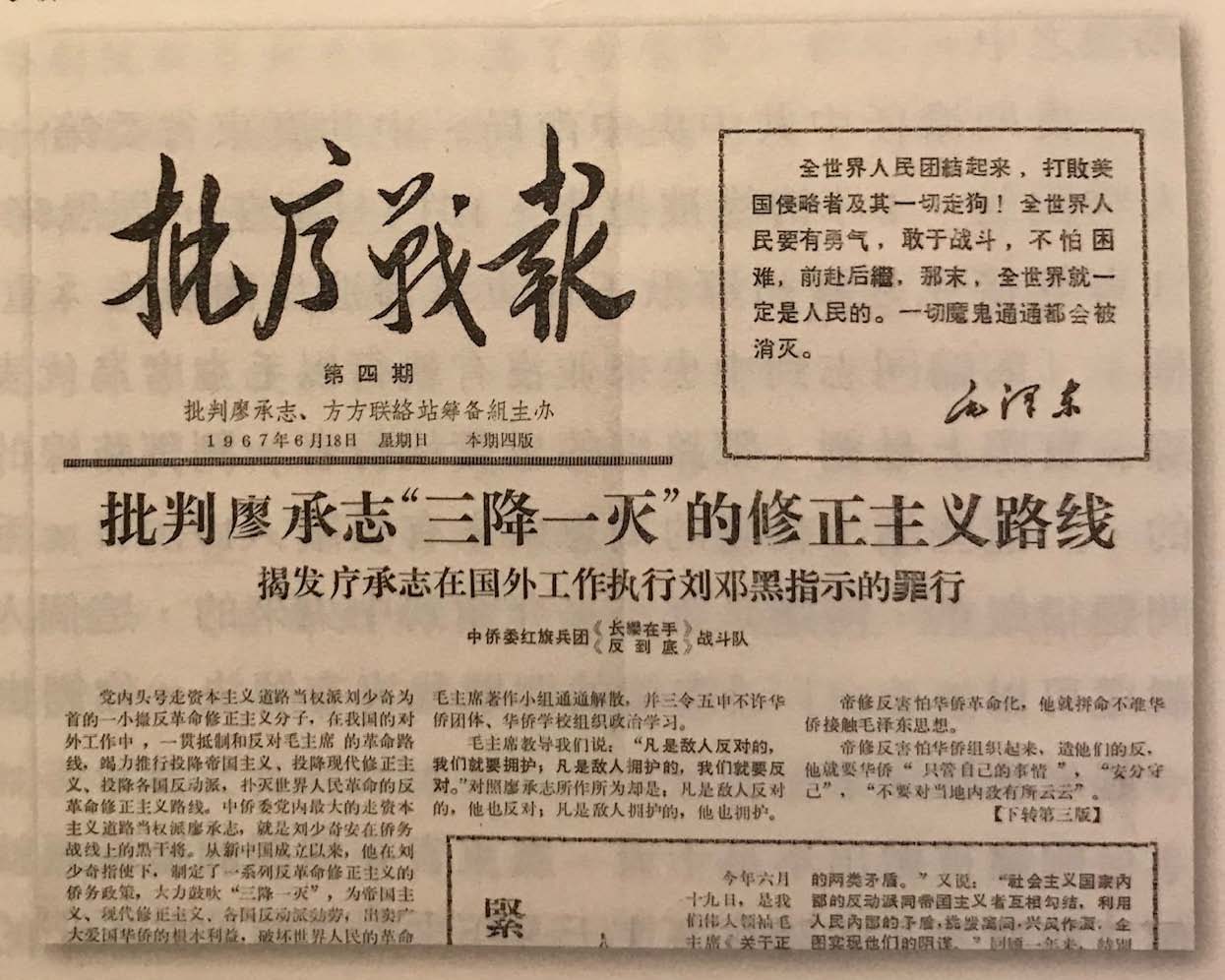

Newsletter published by the Chinese Communist Party to denounce and purge Liao Ch’eng-chih (廖承志), a prominent communist, dated 18 June 1967

In July the following year, Liao Ch’eng-chih (廖承志 or Liao Chengzhi), the “Minister of United Front Work” of the Chinese Communist Party, wrote to President Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), urging for peace dialogue. Madame Chiang published an Open Letter to Liao Ch’eng-chih (給廖承志公開信) from which are the following passages:

“Further, during the so-called ‘Cultural Revolution’ when there was fierce ideological struggle in the political chaos, I heard that you were also targeted in the struggle. Surviving the tiger’s mouth from such a perilous time can be considered very lucky in misfortune. Perhaps you consider that you can find solace in this thought.

The Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun (讀賣新聞) reported a few years ago that the Chinese Communist Party’s central leadership ordered a nationwide compilation and summary of ‘official’ statistics for all 29 provinces and municipalities and those statistics revealed that between 1966 and 1976, approximately 20 million people died from persecution, and the total number of victims who suffered as a result was as high as 600 million people. In regions like Yunnan Province and Inner Mongolia, around 727,000 officials were persecuted, out of which 34,000 of them lost their lives.

The Beijing Daily (北京日報) also reported that during the ‘Cultural Revolution’, approximately 12,000 government officials of Peking municipality were killed. Senior members of the Communist Party, such as Liu Shao-ch’i (劉少奇 Liu Shaoqi), P’eng Te-huai (彭德懷 Peng Dehuai), and Ho Lung (賀龍 He Long), were persecuted to death by forced conscription or starvation. One wonders what thoughts they would have had from beyond the grave had they known of such widespread infighting and brutal means of victimization used by the cadres? …

When all is quiet, I believe you would have reflected on the vicissitudes of your life. Before and after the War of Resistance, were not for the benevolence and concern for old times of the late President, how would you be able to have escaped imprisonment and the threat to your life? Yet now you hope for cooperation for the third time, is it not wishful thinking? How can you not understand the wisdom of the classical allusion in not plucking the melon from the yellow platform three times?

Now on the mainland, internal tribalism is even more rampant and corruption is everywhere. Bribery in public office, the privileged class covering up their crimes and practices of favouritism abound. The abuses of using ‘backdoor channel’ are all too common. That the root of the turmoil is internal does not require further explanation. A person as astute as yourself perhaps should realize that you have been used by pythons your entire life. Anytime there is a change of leadership, the policy also changes. In constant danger, there will come a time when you may not be spared. In the past when Mao the chieftain held political power, there were daily shocks, political struggles, indignities, torture and executions. Everyone was at his mercy while human rights and dignity were utterly disregarded. Turn back while there is still a chance, I hope you will reflect and examine yourself.”

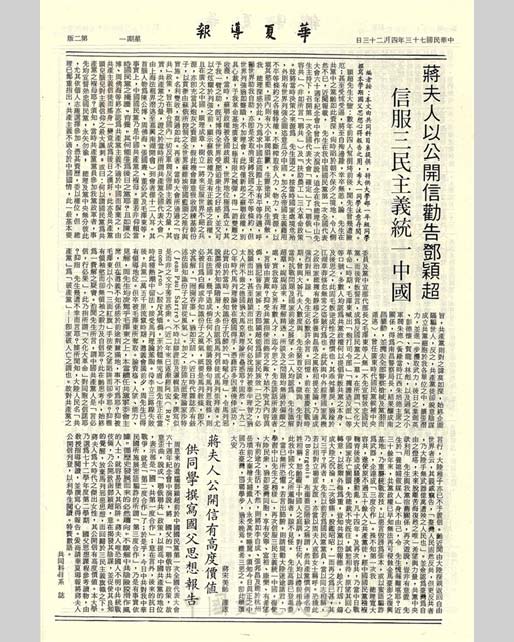

Full text of Open Letter to Madame Teng Ying-ch’ao (鄧穎超) by Madame Chiang Kai-shek, published in Hua-hsia Tao-pao (華夏導報) on 23 April 1984

In February 1984, the 73rd year of the Republic, Madame Chiang once again wrote an open letter in Open Letter to Madame Teng Ying-ch’ao (or Deng Yingchao) (致鄧穎超公開函). Teng Ying-ch’ao (鄧穎超 was the wife of Chou En-lai or Zhou Enlai 周恩來). The following passages are in this letter:

“A few years ago, before and after the downfall of the Gang of Four, I heard that you faced many dangers and was terrified and persecuted to the point of considering suicide. Fortunately, you survived unharmed. With such long membership in the Communist Party, yet you still found yourself in this precarious situation with no guarantee for the next day. It certainly evokes deep sympathy ...

I heard you had said that Chinese Communist Party members are known for “keeping their promises, bringing results with their actions”. Do you mean the pledges made to the people by the so-called ‘Cultural Revolution’? Or do you mean your own near-brushes with misfortune? Apparently people on the mainland refer to the ‘Communist Party’ as the ‘Bankrupt Party’ – meaning the ruin of families and lives. Thus, even mainland’s children do not trust the words and deeds of the Communist Party. Recently I heard from those who returned to the free world after visiting their relatives on the mainland. Their relatives informed them secretly that, “The people of Taiwan are certainly anti-communist but those who are even more anti-communist are the hundreds of millions of unarmed people on the mainland who have suffered greatly.” They also collectively believe that Taiwan is a beacon of freedom, the only hope and source of strength for escape from the sea of suffering in the future. … For the last thirty years or so, the Communist Party regime has long known that it can no longer erode the bastion of national recovery in Kinmen, Matsu, Taiwan, and Penghu. Hence, they have resorted to the old united front work tactics, using nasty slander as capital, or honeyed words as weapon, in an attempt to achieve a ‘third-time cooperation’. Little did one know that during the first time, our President’s magnanimous tolerance of the communists allowed an initially insignificant group of just fifty-odd communist members, after nurturing by the Nationalist Party, to cause upheaval and turmoil for fourteen years. The second time the communists were accommodated, it was during the nation’s life and death struggle in the Sino-Japanese War. The late President, not wishing to dwell on the past, treated them with sincerity and leniency, hoping they would change their ways and prioritize defense against foreign aggression. Little did one know that the communists repaid kindness with evil, seized the opportunity to loot a burning house, and plunged mainland China into ruin. The results from the two previous painful experiences are clear. Even one such mistake is excessive, how can there be a third time?

Madame, in your advanced age of over eighty, you should have no fear. If you can speak sincerely from your heart, please advise those who have gone astray on the mainland to ‘emulate the example of Dr. Sun Yat-sen’, to embrace once again the Three Principles of the People in working towards a unified China. This will allow the people on the mainland to enjoy the same conditions as their compatriots in Taiwan, lives of peace, prosperity, happiness, hope, and a bright future. Otherwise, they will be condemned and scorned in eternity, much like Li Tzu-ch’eng (李自成 1606-1645), Chang Pang-ch’ang (張邦昌 1081-1127), and the metal statues of Ch’in Kuei (秦檜 1091-1155) and his wife, that kneel before the Yue Tomb in Hang-chou. You must know that today’s true China is in Taiwan. It is not too late to learn to walk. I hope you can think carefully about this.”

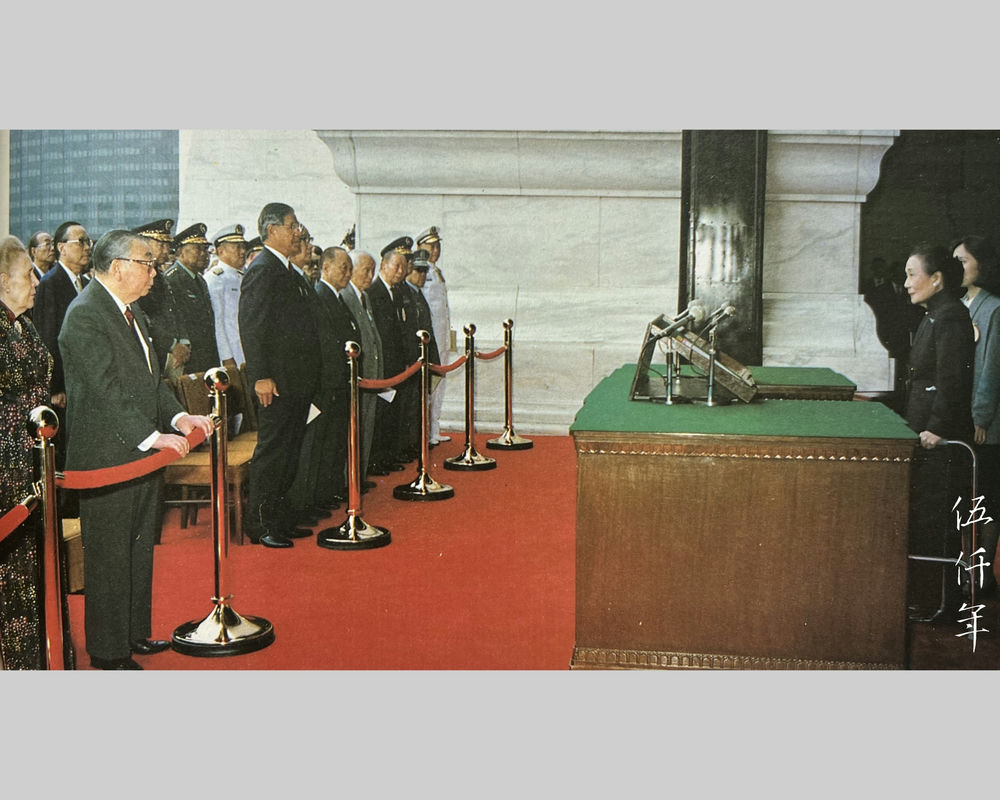

Madame Chiang Kai-shek speaking at the Commemoration of the Birth Centenary of President Chiang Kai-shek held at the National Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall on 31 October 1986

On 31 October 1986, the 75th year of the Republic, Madame Chiang presided over the Commemoration of the Birth Centenary of President Chiang Kai-shek held at the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall in Taipei. She said in her speech:

“This reminds me of the early days when the government relocated to Taiwan. The late President had the opportunity to carefully build Taiwan as an exemplary province embodying the Three Principles of the People. I remember the late President said:

‘We are building Taiwan so that Taiwan can become an anti-communist base, to become an anti-communist fortress and center in the Far East. The purpose of building Taiwan, is for our entire nation, for Asia and for all of humanity worldwide. The spatial scope is not limited to Taiwan alone, and the timeframe is not limited to the present.’ ...

The power unleashed by our belief that Free China Shall Rise Again has already supported the Chinese nation in its all-out resistance against formidable foreign aggression, achieving ultimate victory in a historical milestone. Today it is still without doubt the wellspring of strength for our great anti-communist and national recovery enterprise. It is also the fundamental factor in our unwavering belief that we will eventually succeed. Along the path of our anti-communist struggle, we have indeed faced multiple setbacks and humiliations. However, no one can deny that the Republic of China possesses vast moral and substantive power. How can we be overshadowed by malevolent forces over an extended period? We are the true symbol and harbinger of the genuine resurgence of the Chinese nation.

The late President dedicated his whole life, pouring his heart and soul to the rejuvenation of the nation, the prosperity of the country, and the well-being of the people. All our patriotic comrades and countrymen will strive unrelentingly to rebuild China, so that the spirit of our Founding Father and the late President, along with the radiance of the Three Principles of the People, will be eternal. Let the sons and daughters of the Chinese race follow the footsteps of our eminent forefathers, to complete the magnificent mission that Free China Shall Rise Again! We will be proud and honoured. I, Mei-ling, in my steadfast patriotism, sincerity and confidence, pledge with all my compatriots that we will mutually encourage each other, to follow the examples of our martyrs and advance together on the road to success and victory.”

On 26 July 1995, the 84th year of the Republic, Madame Chiang attended a tribute reception in her honour in response to an invitation from the Majority Leader of the United States Senate, Robert Dole, and Senator Paul Simon, representing the Republican and Democratic parties. She was then 97 years old. Madame Chiang’s speeches and writings are substantial, they have been published in Compilation of Madame Chiang’s Speeches and Writings (1956, the 45th year of the Republic), Further Compilation of Madame Chiang’s Speeches and Writings (1959, the 48th year of the Republic), Madame Chiang’s Collected Speeches and Writings (1977, the 66th year of the Republic) and The Collected Works of Soong Mei-ling in Five Volumes (2015, the 104th year of the Republic).

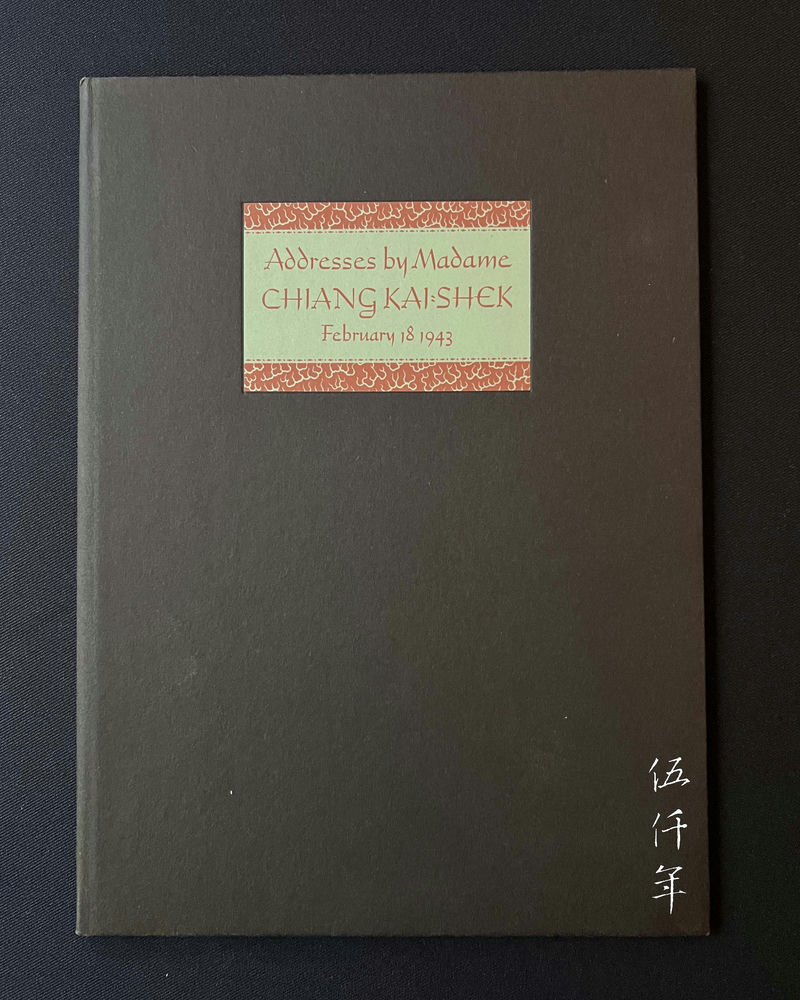

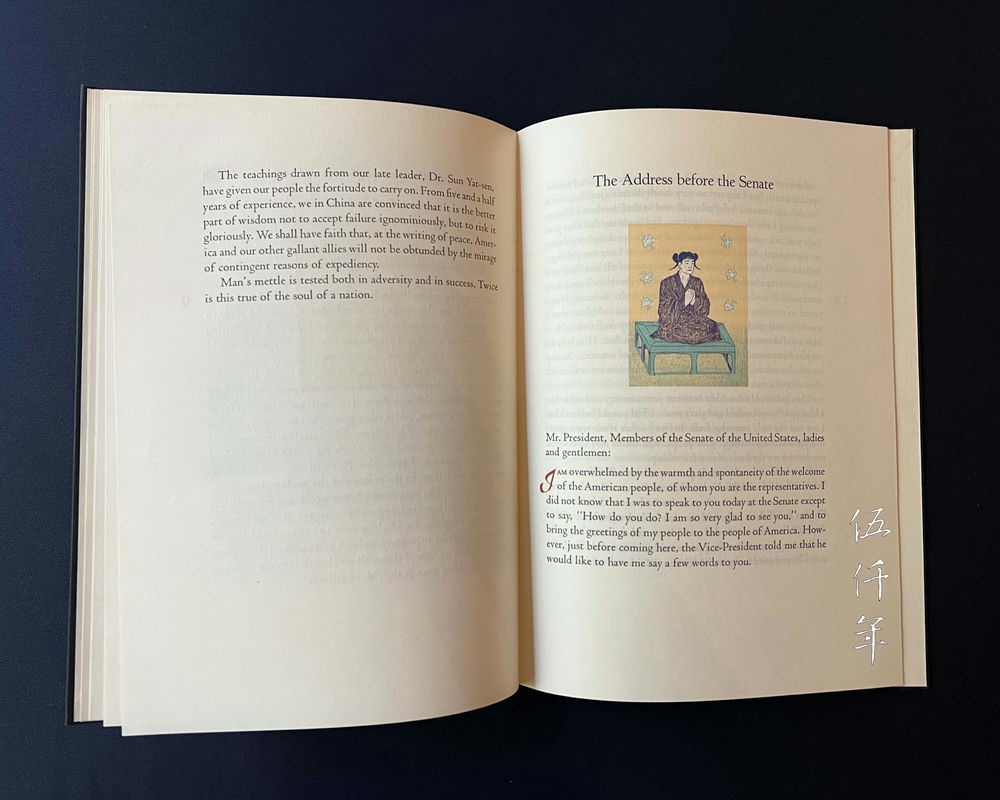

The addresses delivered by Madame Chiang Kai-shek to the United States Senate and the House of Representatives on 18 February 1943 were printed into book form in April that year. The title is Addresses by Madame Chiang Kai-shek, February 18 1943. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

Title page of Addresses by Madame Chiang Kai-shek, February 18 1943. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

Inside page of Addresses by Madame Chiang Kai-shek, February 18 1943, with address to the House of Representatives. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

Inside page of Addresses by Madame Chiang Kai-shek, February 18 1943, with address to the Senate. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

Inside page of Addresses by Madame Chiang Kai-shek, February 18 1943, with month and year of publishing. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

Harking back to mid-November 1942, the 31st year of the Republic, which happened to be the fifth year of the War of Resistance Against Japan, Madame Chiang’s chronic illness became severe, and she traveled to the United States for medical treatment. She arrived in New York on 27 November and was admitted to the Presbyterian Hospital. She was discharged in February the following year. President Roosevelt and his wife invited Madame Chiang to stay at their private residence in Hyde Park for six days. On 18 February, she was invited to Washington to address the US Congress, to both the Senate and the House of Representatives. Her address in the House of Representatives lasted approximately twenty one minutes and was broadcasted by radio, reaching countless listeners. This address had a far-reaching impact on American politicians. On 4 April, Madame Chiang delivered an outdoor address at Hollywood Bowl, in Hollywood, Los Angeles. It lasted 40 minutes and was her longest speech during her tour of the United States in 1943, and greatly influenced the American cultural world and the public.

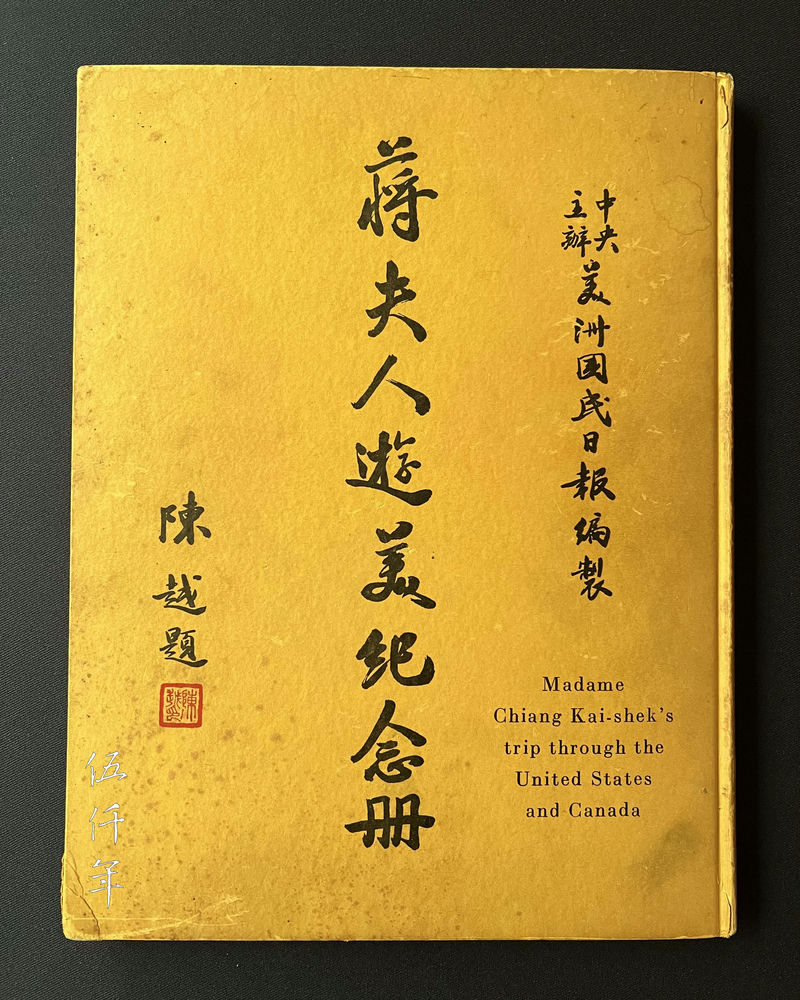

Cover of A Record of Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s American Tour, published by Kuo-min Jih-pao Newspaper on 7 July 1943. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

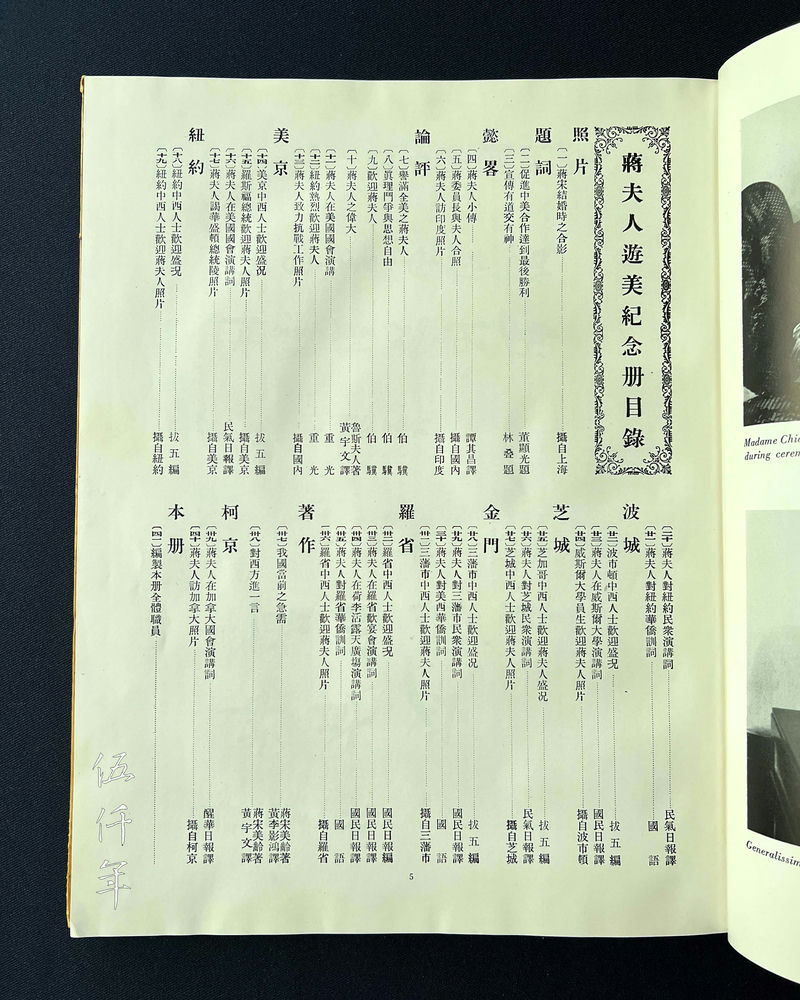

Index of A Record of Madame Chiang Kai-sheik’s American Tour, published by Kuo-min Jim-pao Newspaper on 7 July 1943. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

In 1943, the 32nd year of the Republic, Madame Chiang visited six major cities in the United States, starting from Washington, D.C., and ending in Los Angeles. On 1 March she arrived in New York from Washington, starting her official visit to New York.

Madame Chiang Kai-shek addressing the United States House of Representatives on 18 February 1943. Photograph courtesy Mr. Roy Delbyck

On 6 March she arrived in Boston and the following day, she returned to speak at her alma mater, Wellesley College.

Madame Chiang Kai-shek visiting Wellesley College, her alma mater, on 6 March 1943. Photograph courtesy Mr. Roy Delbyck

On 9 March she returned to New York, and on 19 March she arrived in Chicago from New York.

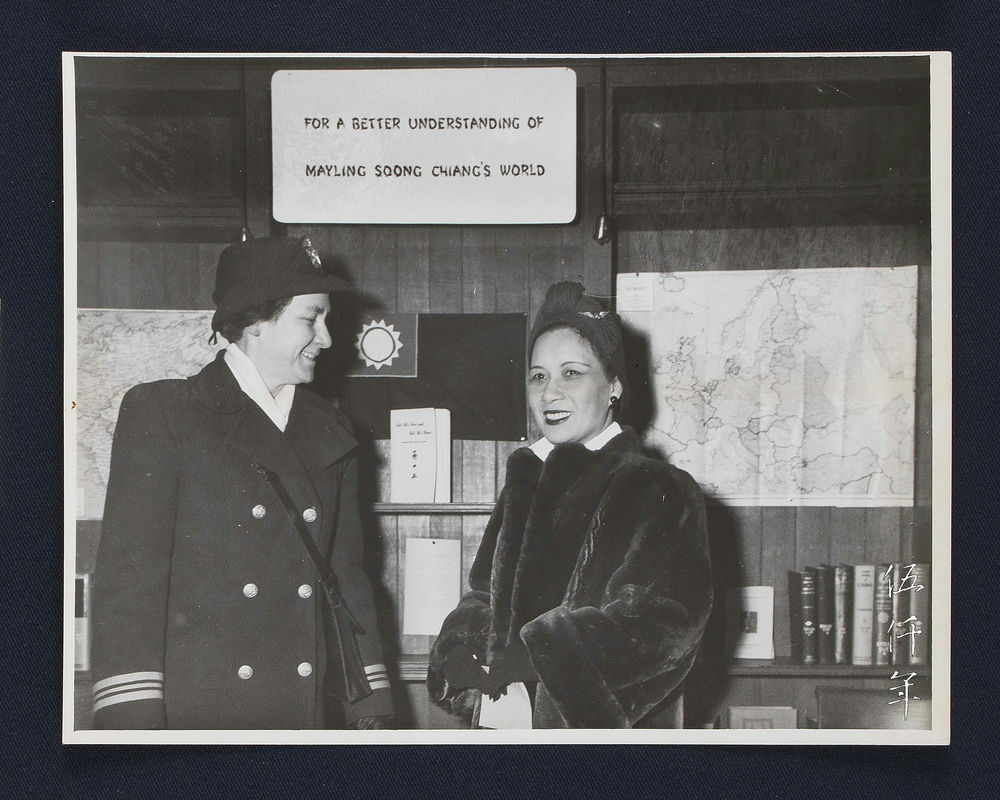

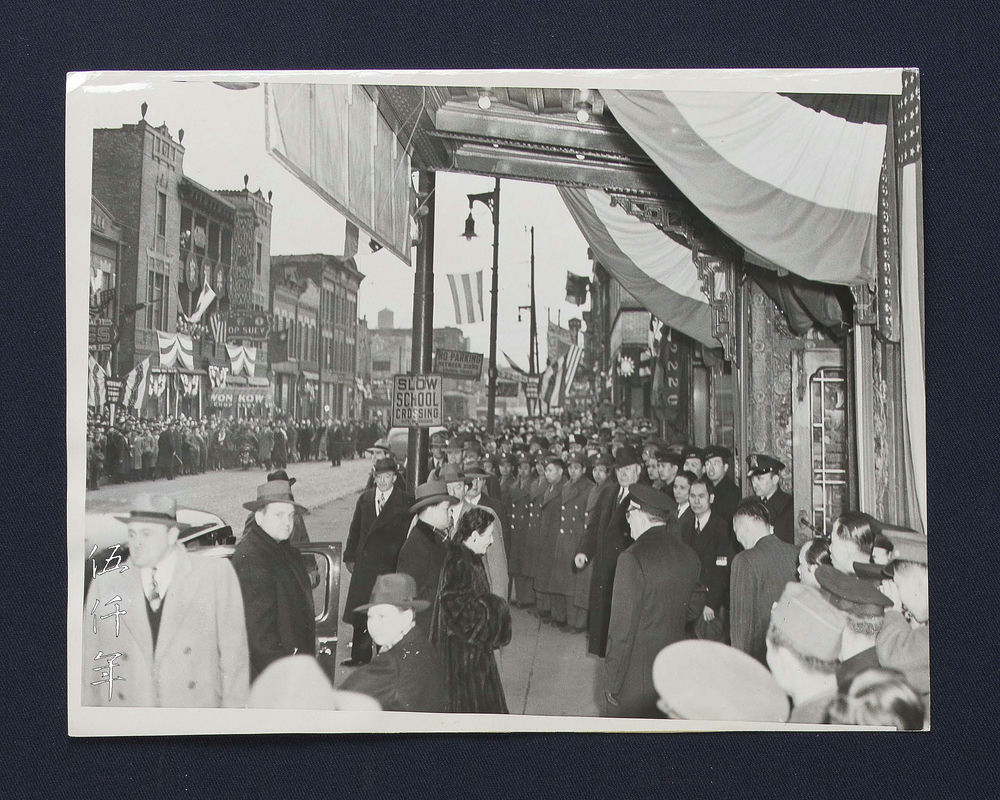

Madame Chiang Kai-shek arriving at Chinatown’s City Hall in Chicago on 21 March 1943. Photograph courtesy Mr. Roy Delbyck

On 25 March she arrived in San Francisco from Chicago

Madame Chiang Kai-shek attending a banquet hosted by the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce in the evening of 26 March 1943. Sitting to the left is Mayor Rossi of San Francisco. Photograph courtesy Mr. Roy Delbyck

On 31 March she arrived in Los Angeles from San Francisco. in the evening of 2 April Madame Chiang was honoured with a banquet at the Ambassador Hotel attended by over 1,500 guests from all vocations in Los Angeles. On Sunday, 4 April, at 3 p.m., she participated in the event titled On the Occasion of the Address of Madame Chiang Kai-Shek to the People of Los Angeles at Hollywood Bowl, attended by approximately 30,000 people. On 10 April she visited Chinatown, and on 11 April she left Los Angeles for New York.

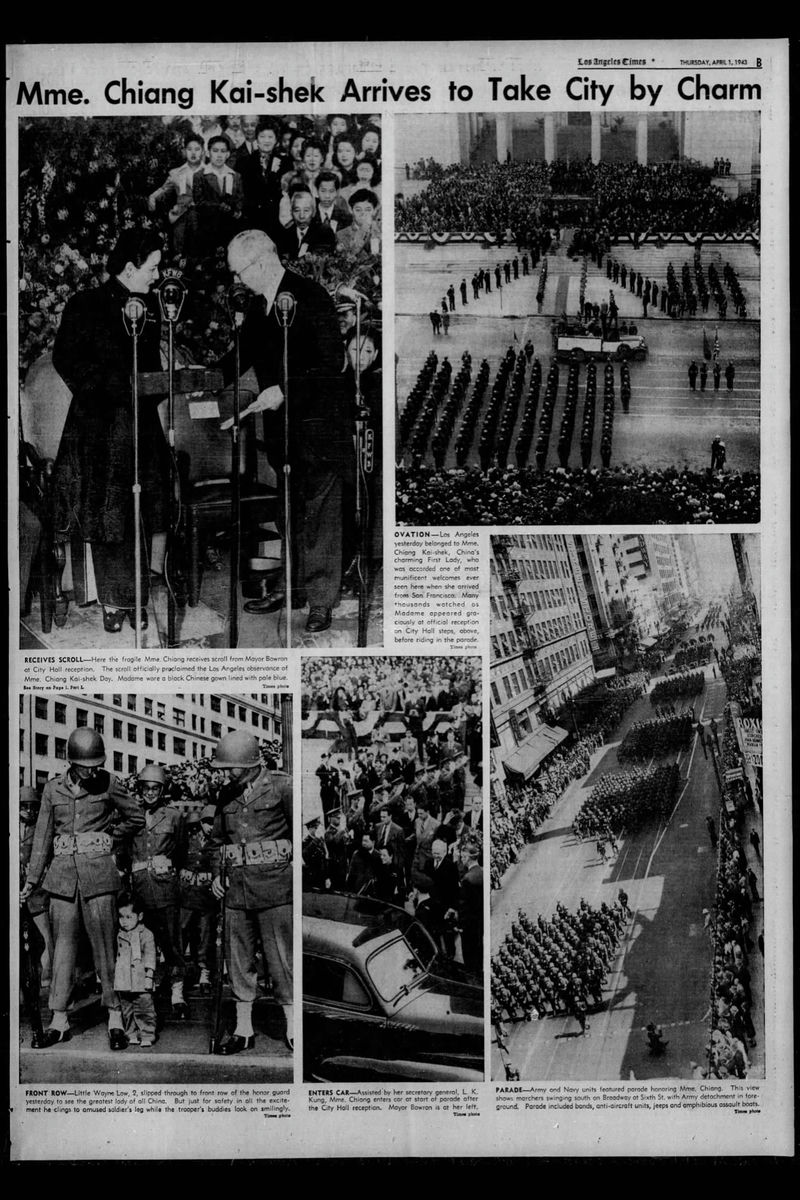

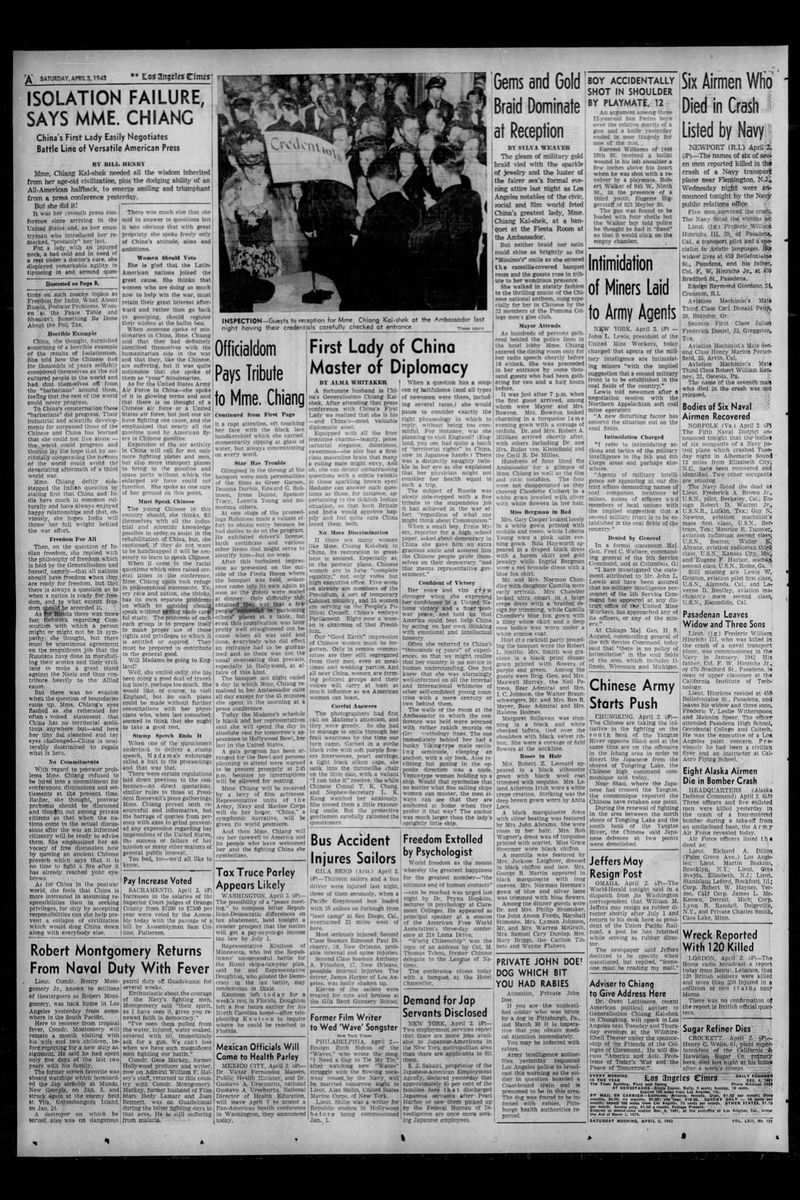

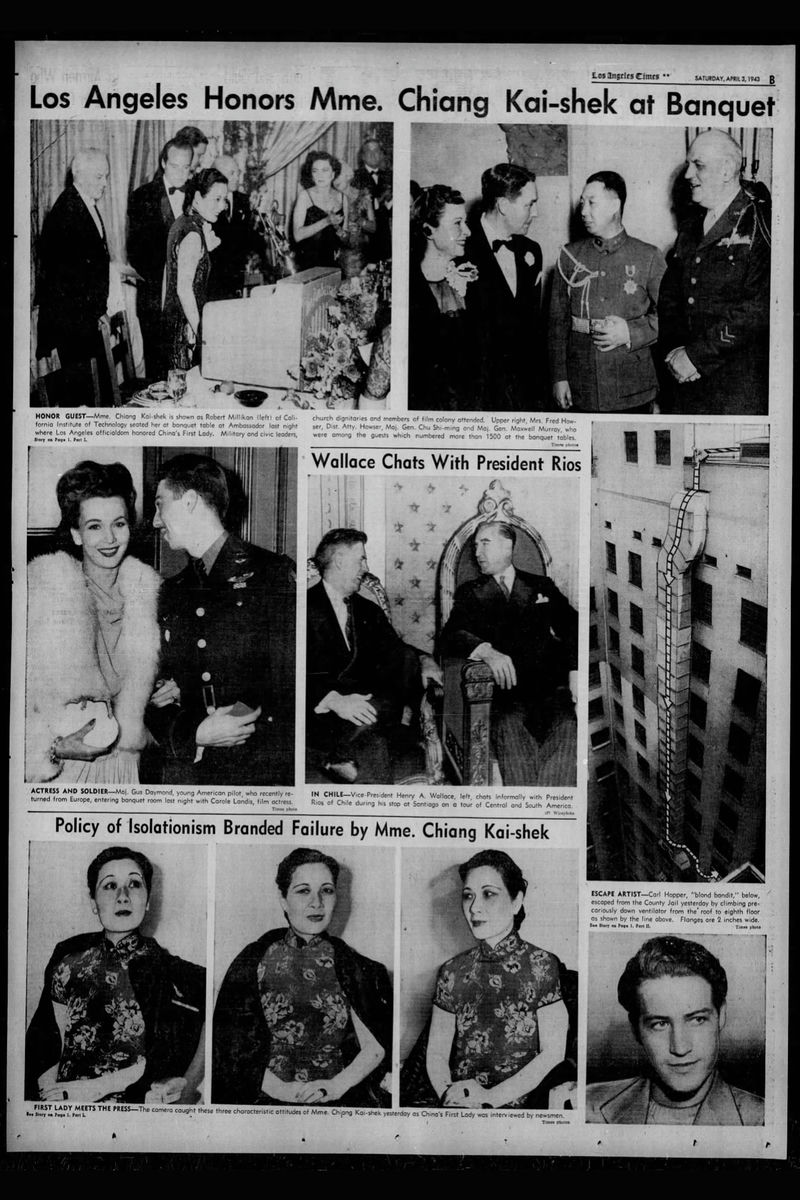

Full page coverage of Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s arrival in Los Angeles, Los Angeles Times dated 1 April 1943

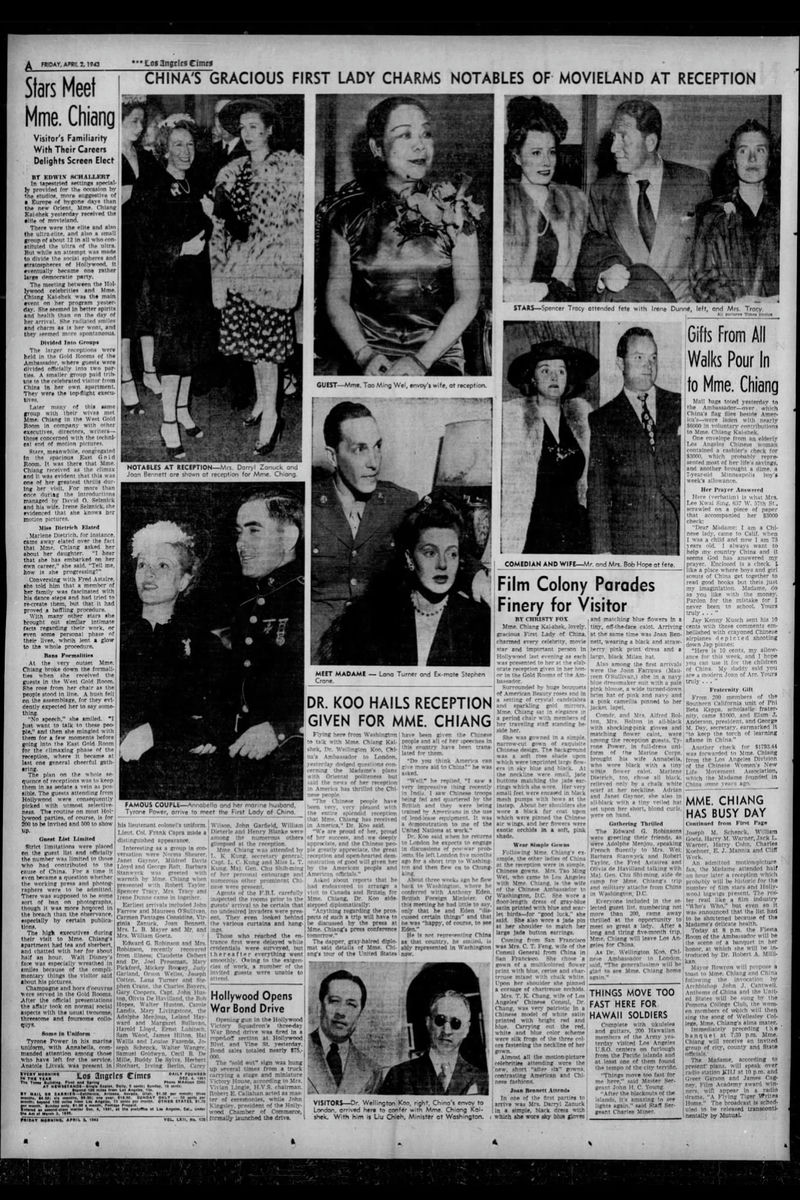

Full page coverage of Madame Chiang Kai-shek attending the evening banquet at the Ambassador Hotel on 1 April, Los Angeles Times dated 2 April 1943

News caption: First Lady of China, Master of Diplomacy, with additional page covering 1 April banquet, Los Angeles Times dated 3 April 1943

News caption: First Lady of China, Master of Diplomacy, with additional page covering 1 April banquet, Los Angeles Times dated 3 April 1943

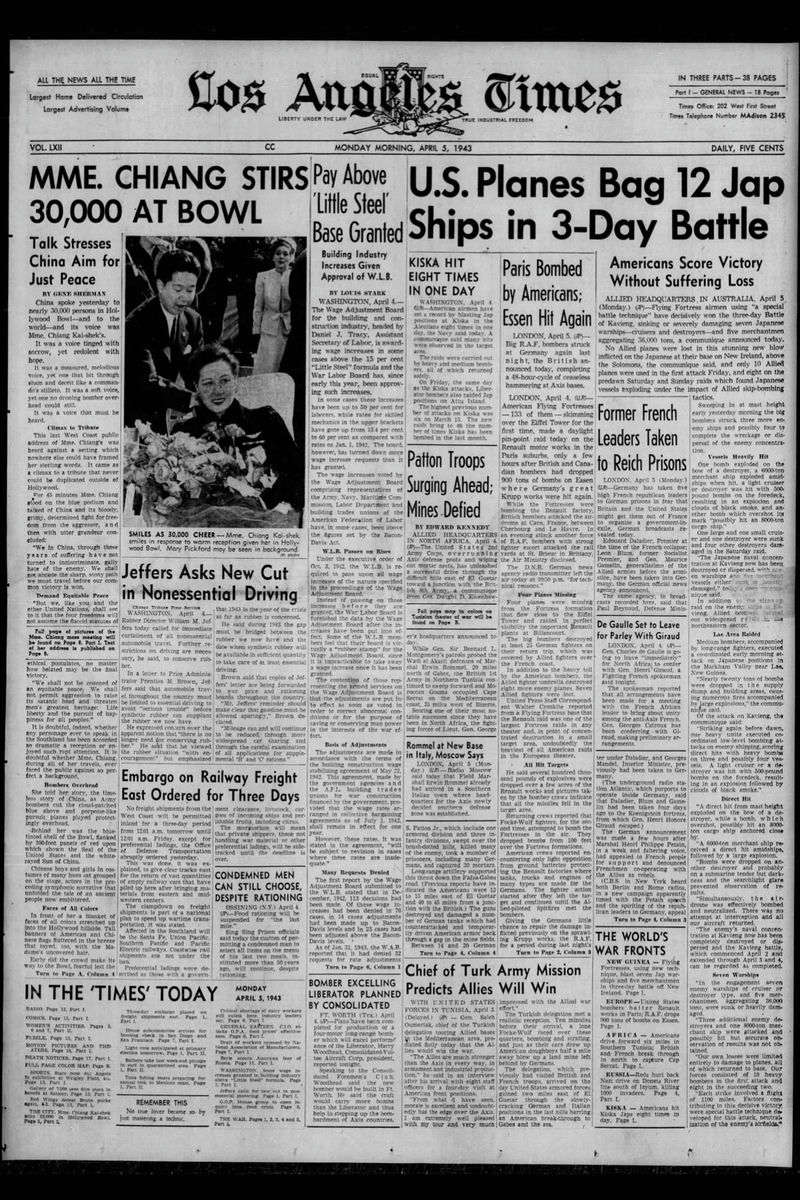

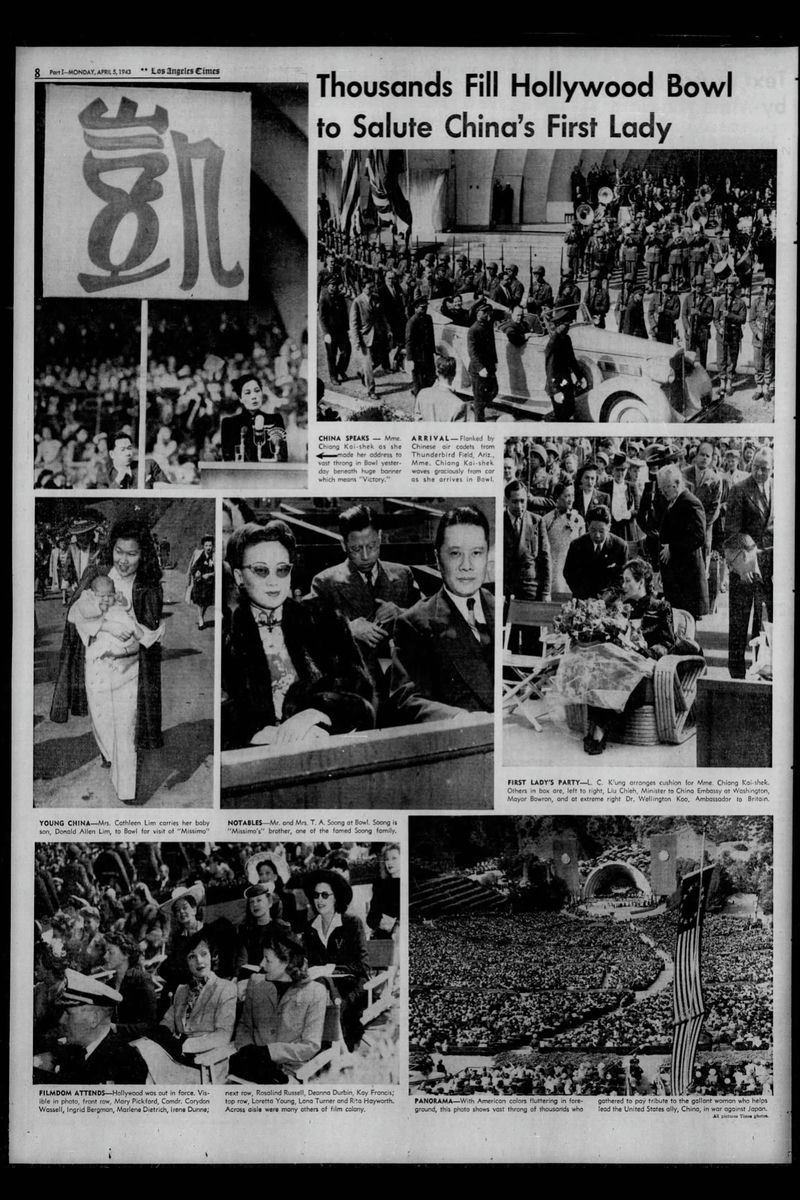

News coverage of Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s address at Hollywood Bowl attended by 30,000 on 4 April, Los Angeles Times dated 5 April 1943

Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s address at Hollywood Bowl attended by 30,000

Full page coverage of Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s address at Hollywood Bowl, Los Angeles Times dated 5 April 1943

Madame Chiang Kai-shek addressing the audience at Hollywood Bowl on 4 April 1943. Photograph courtesy Mr. Roy Delbyck

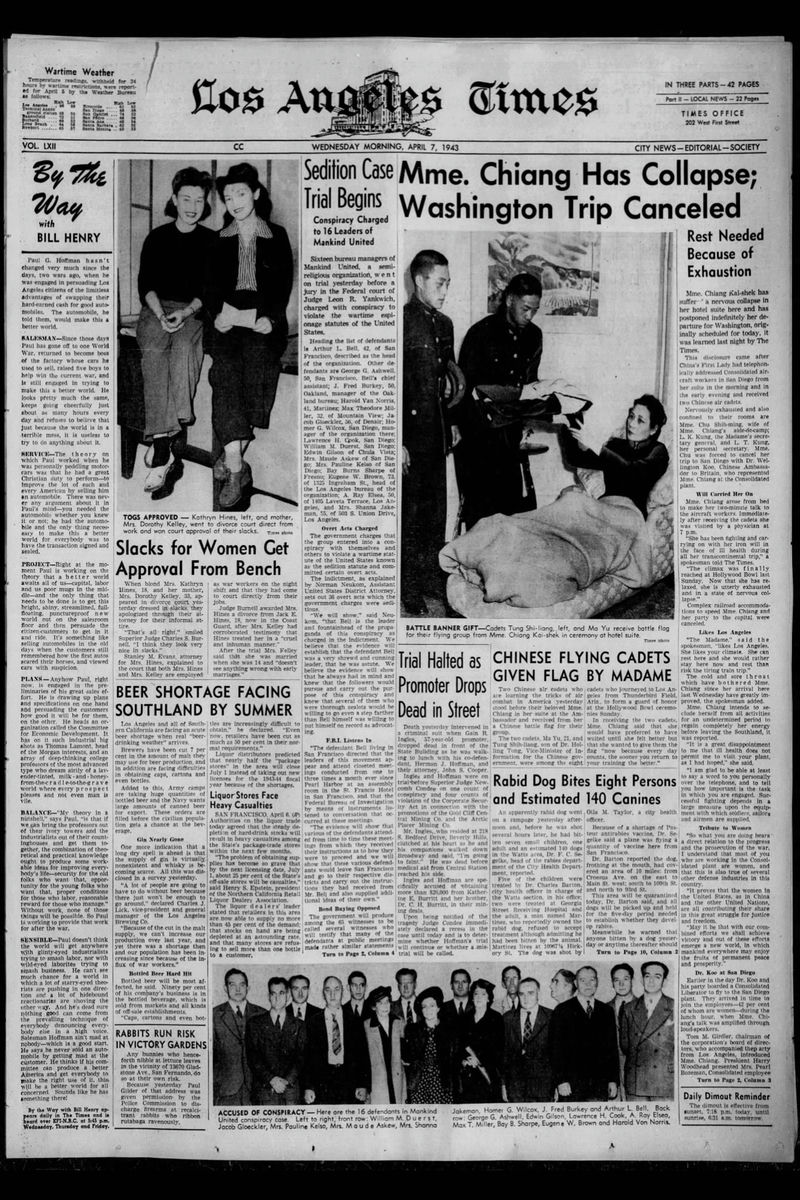

News coverage of Madame Chiang Kai-shek falling ill on 6 April, Los Angeles Times dated 7 April 1943

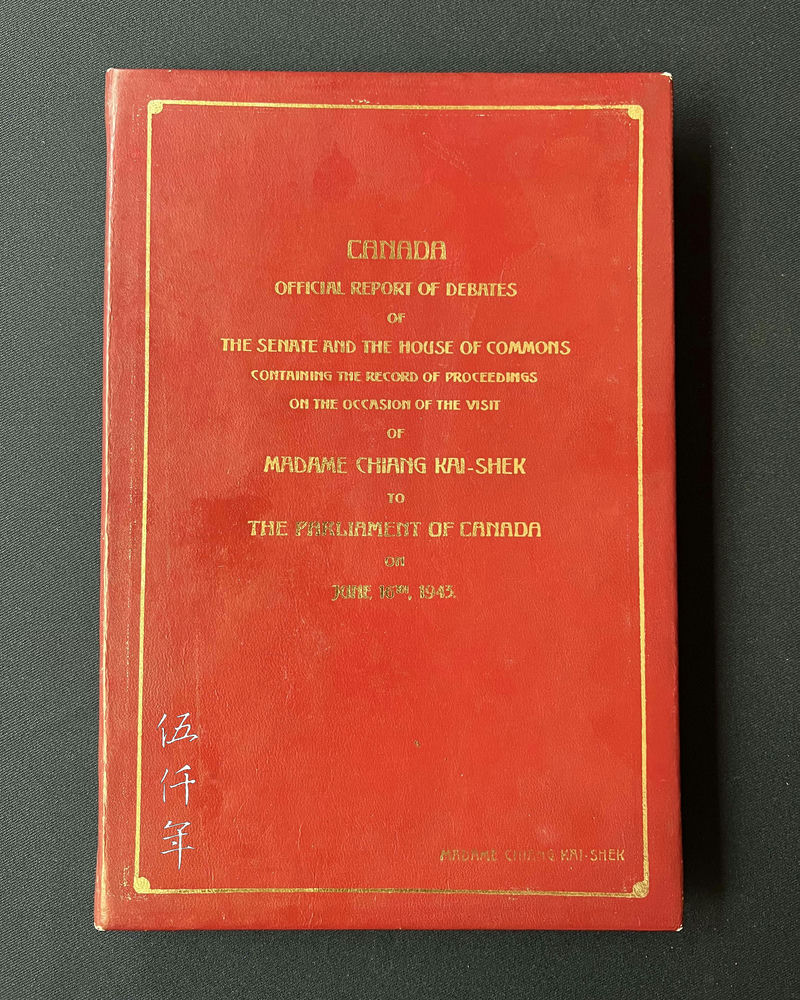

On June 16, she visited the Canadian Parliament to deliver her speech.

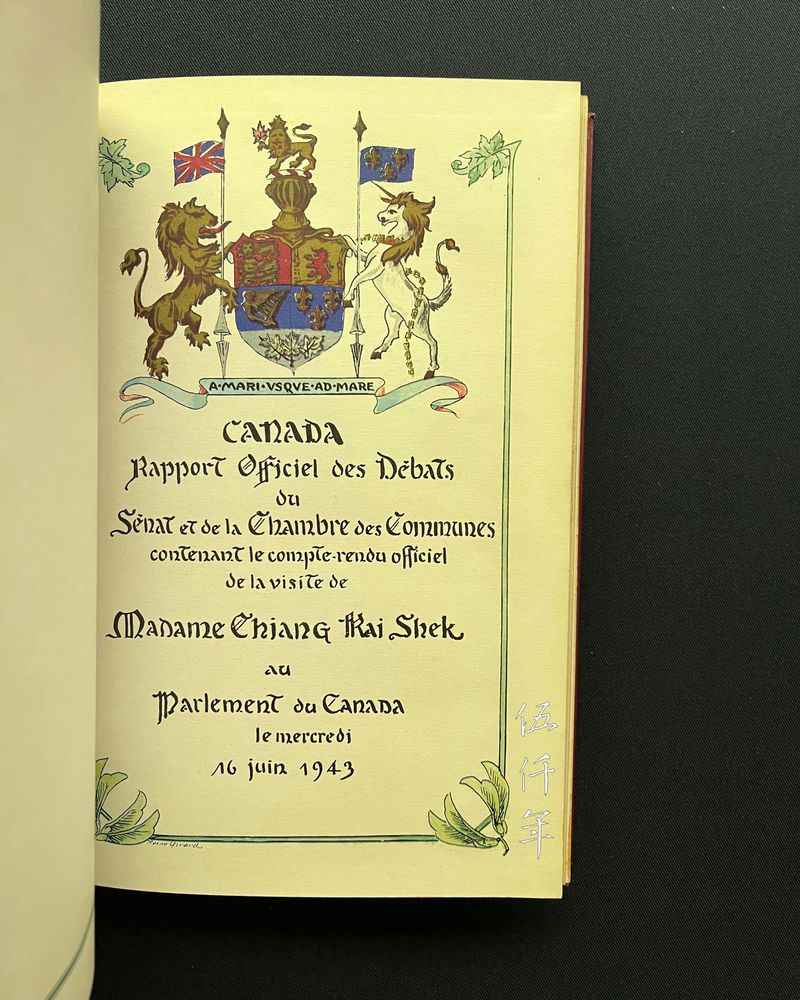

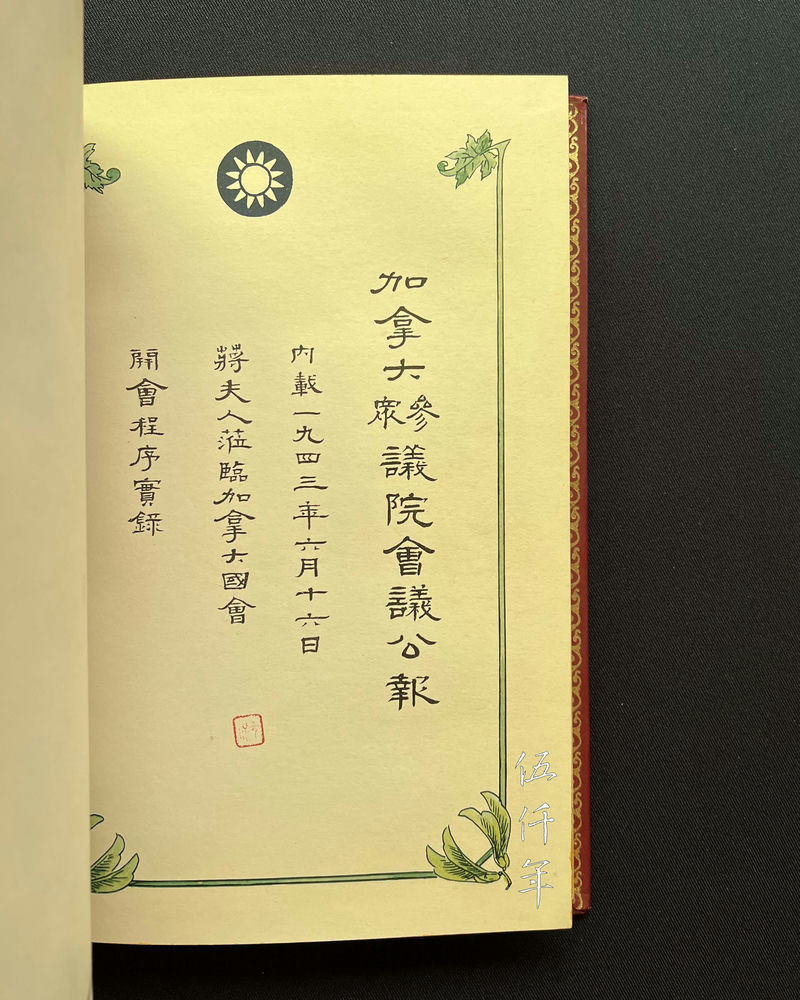

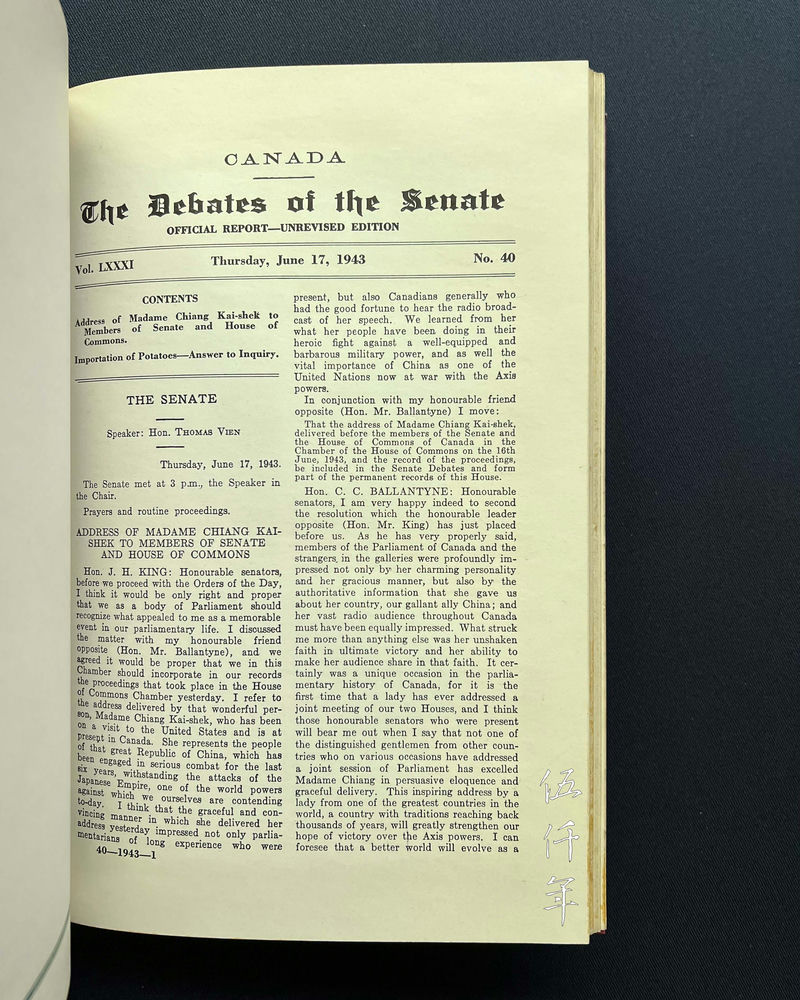

Half a year after Madame Chiang Kai-shek addressed the Canadian Parliament on 16 June 1943, the Canadian Parliament commissioned two custom made leather bound copies of Madame Chiang’s address and associated Parliamentary Proceedings. The Chinese title page was translated by the Chinese Embassy, with the Chinese National Emblem on the top of the page. Thomas Vien, Speaker of the Senate, then presented the two commissioned copies to Ambassador Liu Shih-shun (劉師舜公使), one to him and one to Madame Chiang. The copy displayed here belonged to Madame Chiang, with her name embossed in gold at the lower right on the front cover of the book. Photograph courtesy Private Collection

English title page of custom leather bound book on Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s address to the the Parliament of Canada. Former property of Madame Chiang Kai-shek

Chinese title page of custom leather bound book on Madame Chiang Kai-sheik’s address to the Parliament of Canada. Former property of Madame Chiang Kai-shek

Inside page of custom leather bound book on Madame Chiang Kai-shek’s address to the Parliament of Canada. Former property of Madame Chiang Kai-shek

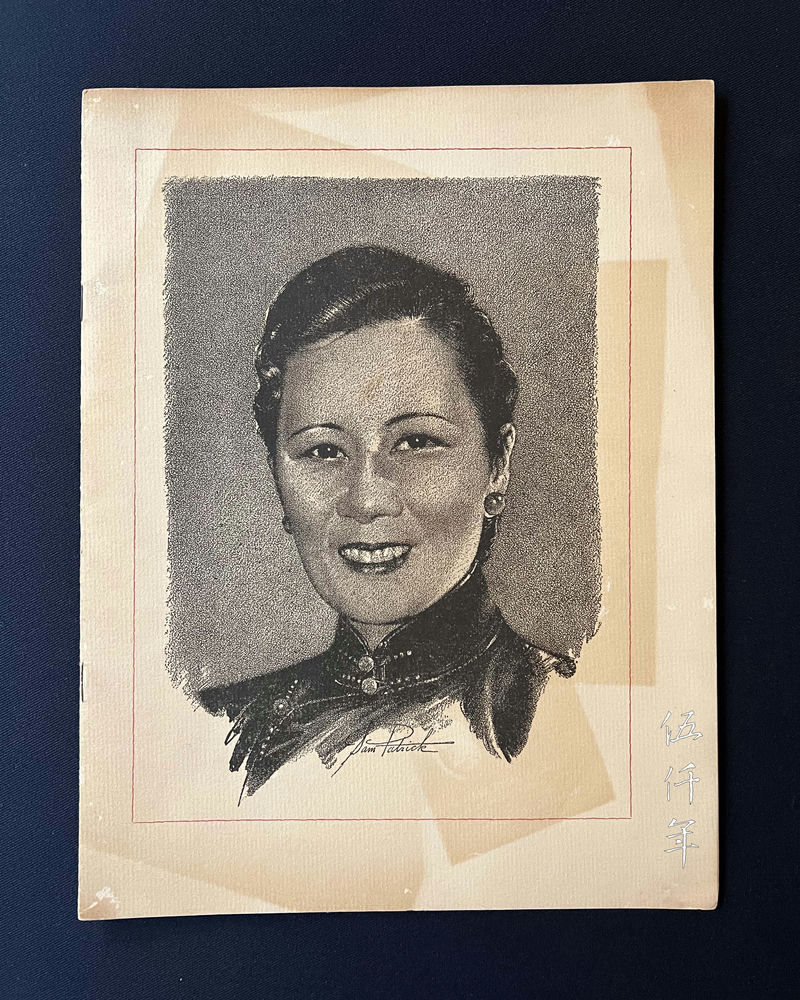

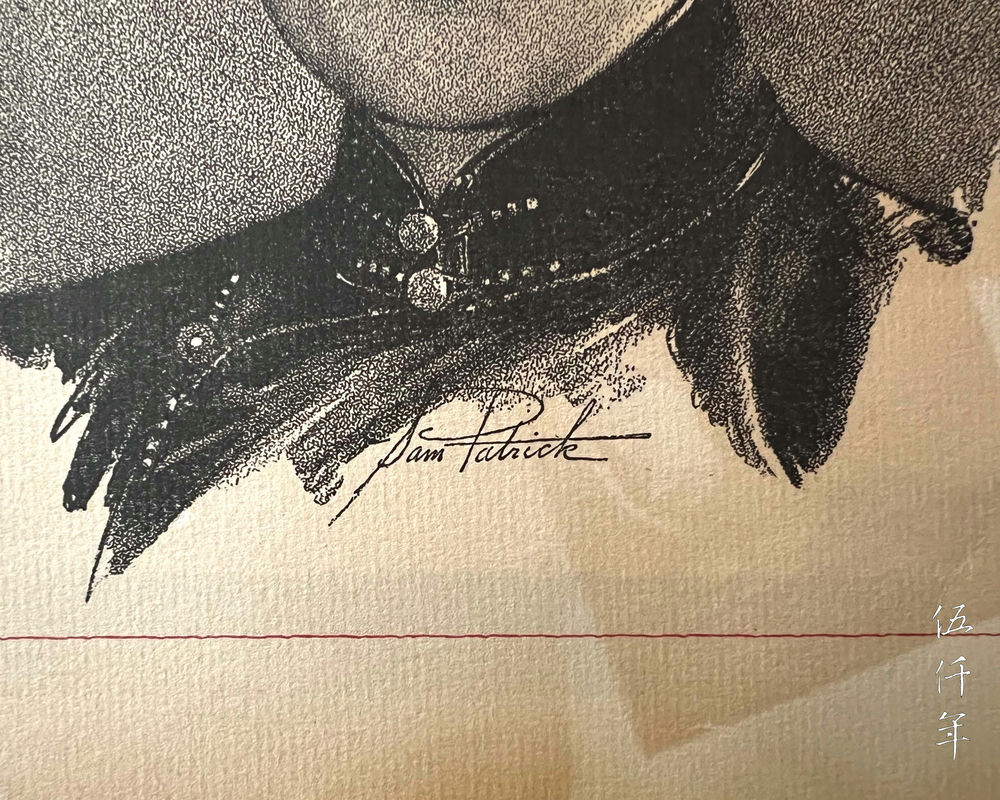

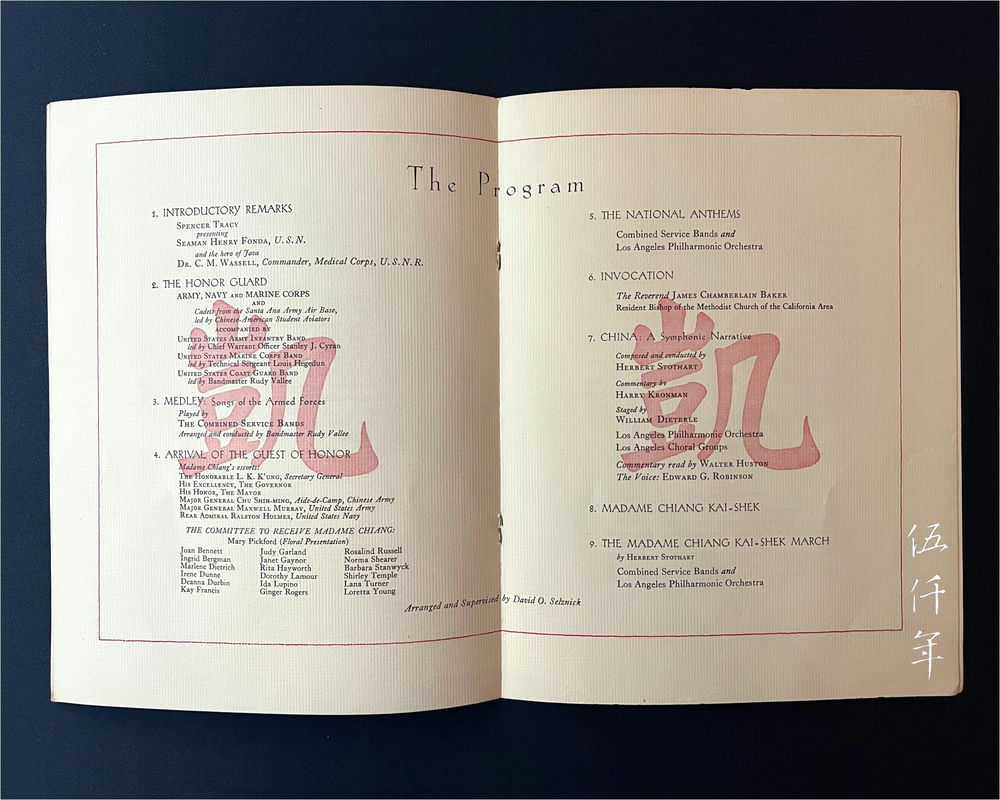

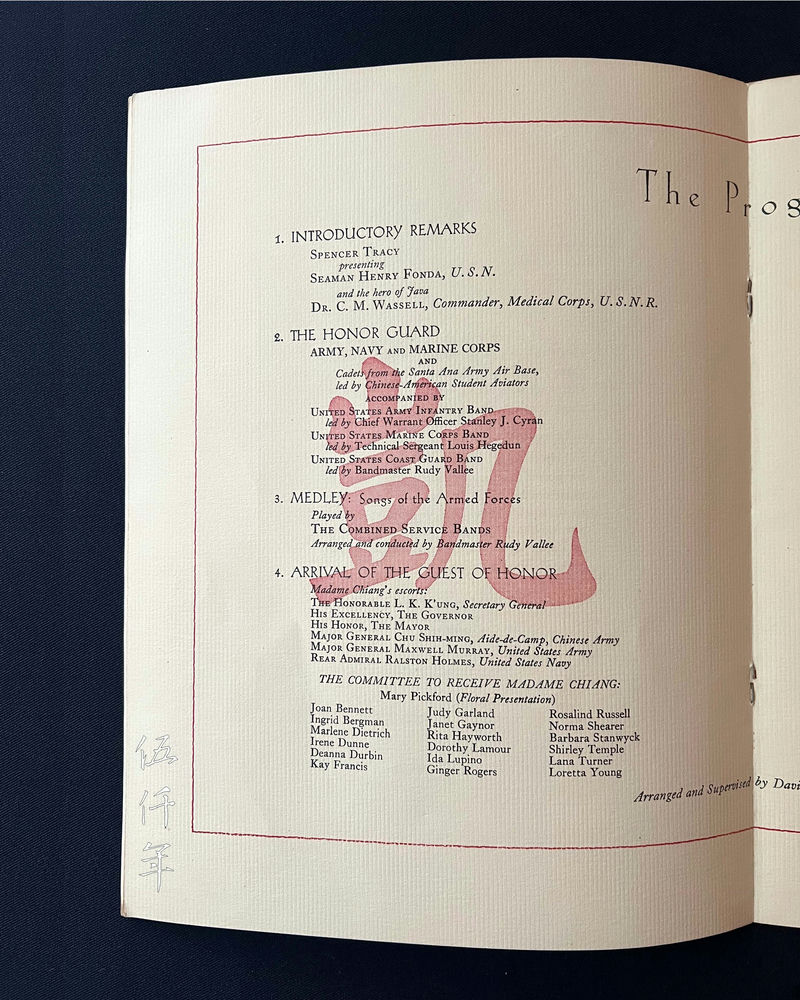

The Programme for On the Occasion of the Address of Madame Chiang Kai-Shek to the People of Los Angeles held at Hollywood Bowl can occasionally be found in antiquarian bookshops. The cover of the programme features a portrait of Madame Chiang by the American illustrator Samuel James Patrick (1901-1987), who was employed by the Los Angeles Times. His signature “Sam Patrick” is seen below the portrait.

Portrait of Madame Chiang Kai-shek on the front cover of the Programme for On the Occassion of the Address of Madame Chiang Kai-shek to the People of Los Angeles

Artist’s signature below the portrait on front cover the Programme

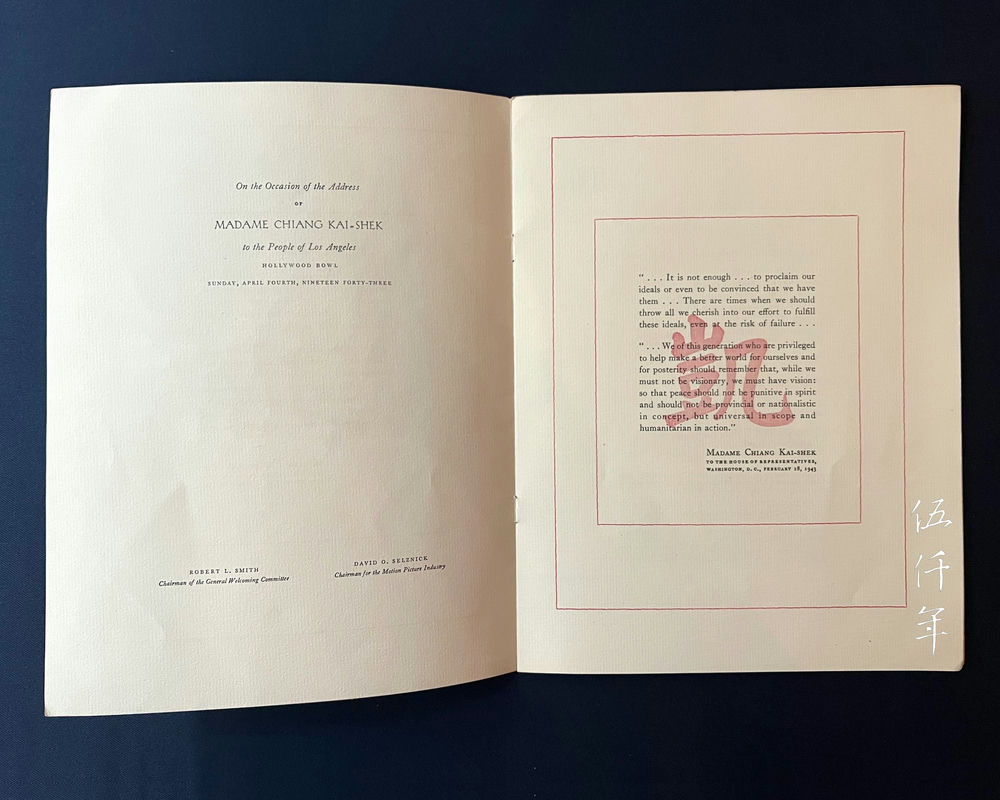

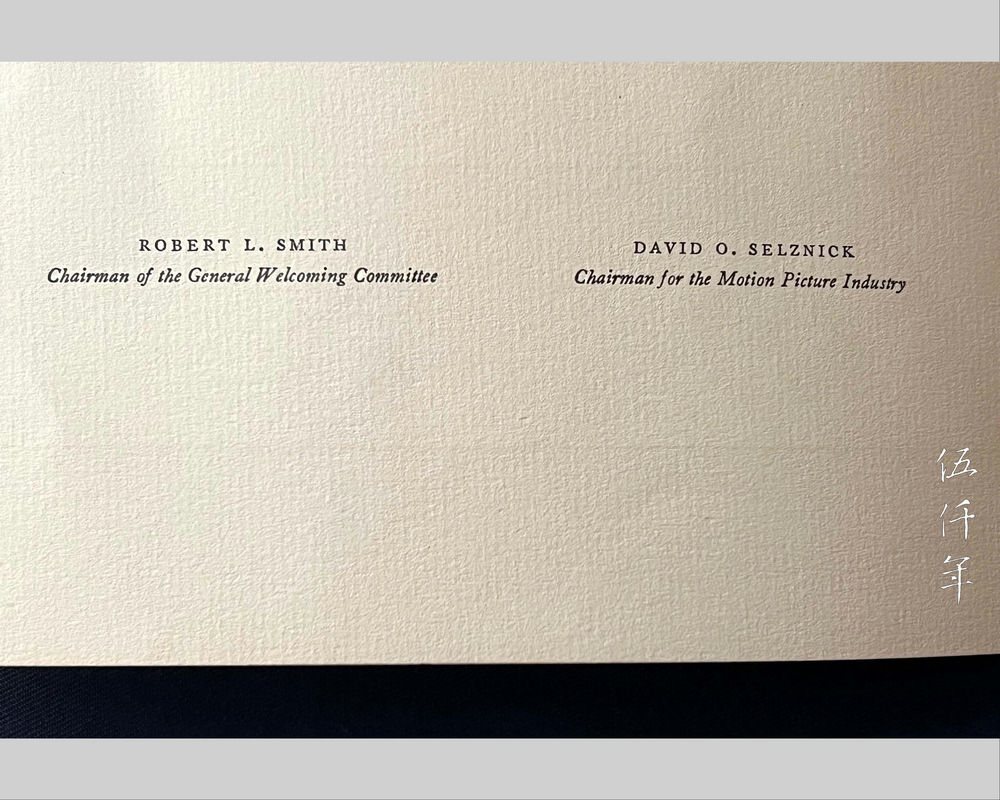

At the top of the first inside page, the text states the event’s title as On the Occasion of the Address of Madame Chiang Kai-Shek to the People of Los Angeles, along with details of the location, day of the week, date, and year. At the bottom of the first inside page, there are two names. “David O. Selznick” (1902–1965) is printed on the right with the title “Chairman for the Motion Picture Industry”. “Robert L. Smith” is printed on the left with the title “Chairman of the General Welcoming Committee”.

First page and second page inside the Programme

First page inside the Programme

Upper part of first page inside the Programme with the day, month and year of the Occassion printed

Lower part of first page inside the Programme with the names of David O. Selznick and Robert L. Smith printed

Portrait of David O. Selznick

David O. Selznick was a film producer, screenwriter, and president of a film production company. His notable productions include the 1939 film “Gone with the Wind” and the 1940 film “Rebecca”. This event On the Occasion of the Address of Madame Chiang Kai-Shek to the People of Los Angeles was also produced by him. Robert L. Smith was the president of the Los Angeles Daily News.

Second page inside the Programme

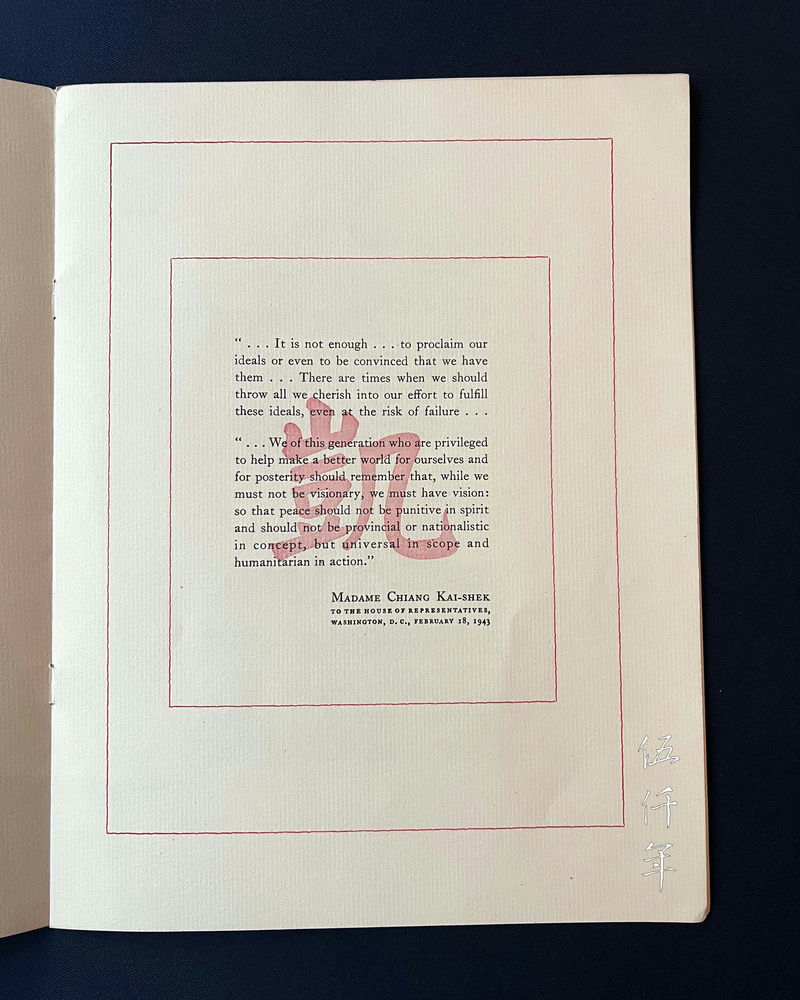

Second page inside the Programme with excerpts of Madame Chiang Kai-sheik’s address to Congress

The second inside page contains two paragraphs excerpted from Madame Chiang’s speech delivered on 18 February in the House of Representatives. They lines are:

“… It is not enough … to proclaim our ideals or even to be convinced that we have them … There are times when we should throw all we cherish into our effort to fulfill these ideals, even at the risk of failure …

“… We of this generation who are privileged to help make a better world for ourselves and for posterity should remember that, while we must not be visionary, we must have vision: so that peace should not be punitive in spirit and should not be provincial or nationalistic in concept, but universal in scope and humanitarian in action.”

This is indicative that Madame Chiang’s address in Congress made a lasting impression on members of the American government and the public at large

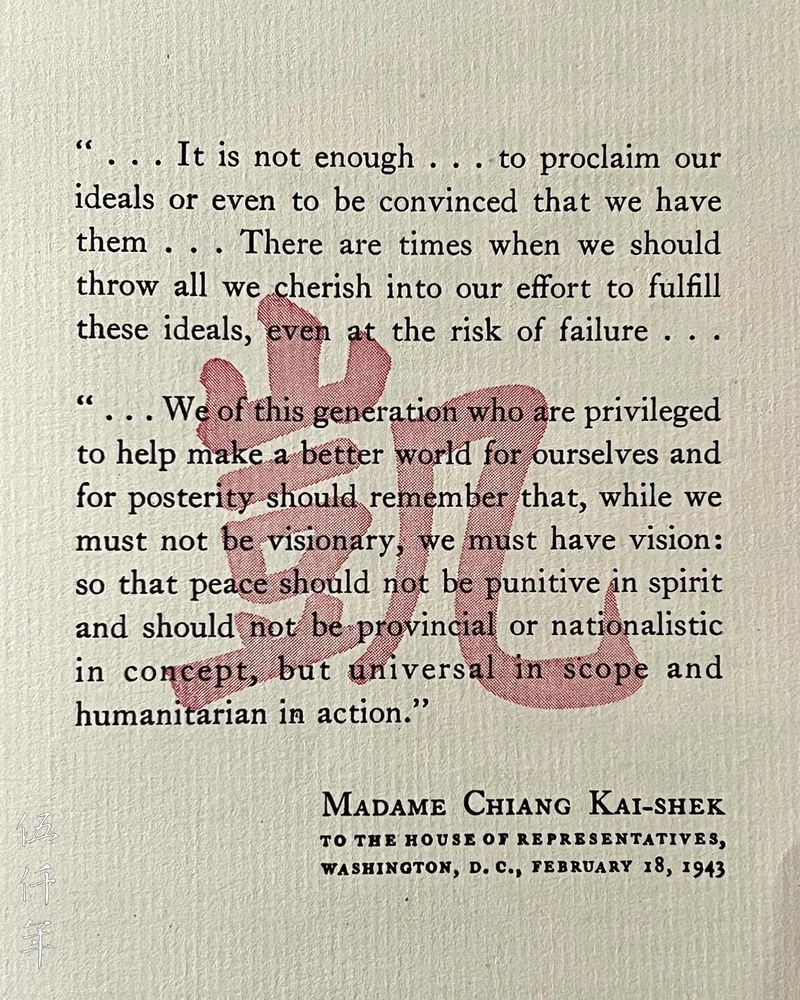

Third page and fourth page inside the Programme

Third page inside the Programme

First scene of Introductory Remarks printed on the upper part of third page inside the Programme

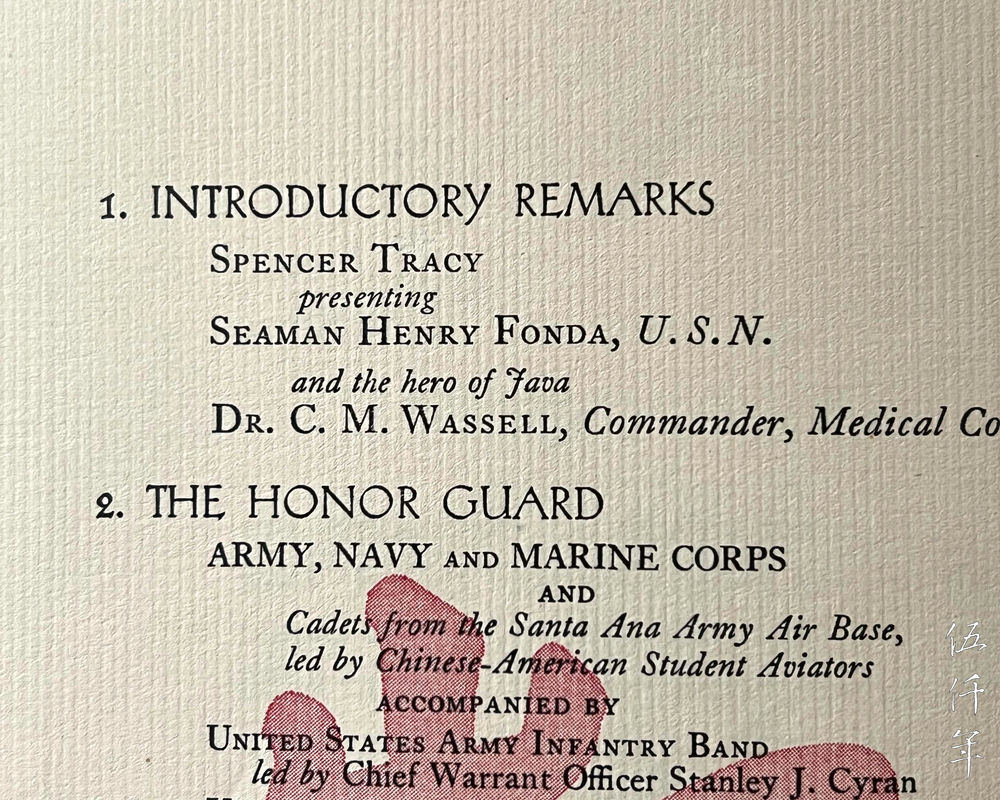

Pages three and four of the Programme describe the schedule. The first scene is Introductory Remarks, presented by the actor Spencer Tracy (1900-1967), the actor Henry Fonda (1905-1982) who had volunteered for the Navy, and the Navy hero Dr. Corydon M. Wassell (1884-1958).

Portrait of Spencer Tracy

Portrait of Henry Fonda

Portrait of Corydon M. Wassell

The second scene is The Honor Guard, consisting of the U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps, including cadets from the Santa Ana Army Air Base, led by Chinese-American student aviators. The Honor Guard also included the U.S. Army Infantry Band, the U.S. Marine Corps Band, and the U.S. Coast Guard Band.

The third scene is Medley: Songs of the Armed Forces, performed by The Combined Service Bands.

Printed on the lower part of third page inside the Programme is Mary Pickford’s assignment to present the bouquet

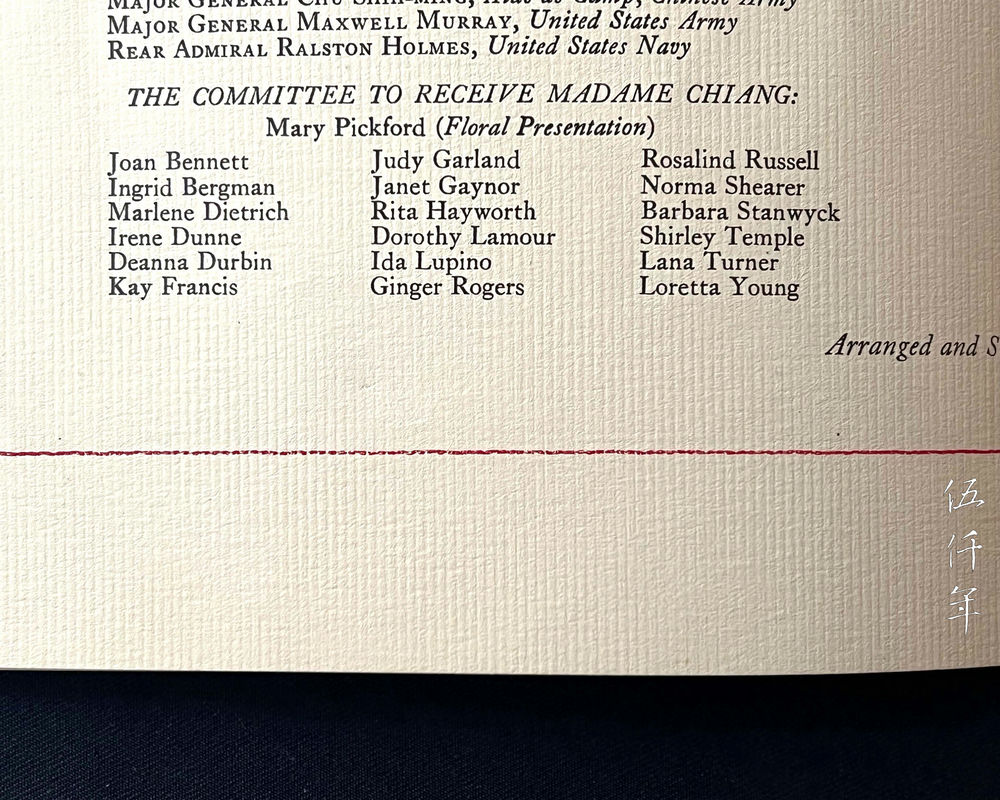

The fourth scene is Arrival of the Guest of Honor. Madame Chiang’s escorts were her nephew Secretary-General K’ung Ling-k’an (孔令侃), the Governor of California, the Mayor of Los Angeles, Major General Chu Shih-Ming of the Chinese Army, Major General Maxwell Murray of the U.S. Army, and Rear Admiral Ralston Homes of the U.S. Navy. The actress Mary Pickford (1892-1979) was assigned to present the bouquet.

Portrait of Mary Pickford (1892-1979)

The Committee to Receive Madame Chiang consisted entirely of eminent female actresses, totaling eighteen in number. They were:

Portrait of Joan Bennett (1910–1990)

Portrait of Ingrid Bergman (1915–1982)

Portrait of Marlene Dietrich (1901–1992)

Portrait of Irene Dunne (1898–1990)

Portrait of Deanna Durban (1921–2013)

Portrait of Kay Francis (1905–1968)

Portrait of Judy Garland (1922–1969)

Portrait of Janet Gaynor (1906–1984)

Portrait of Rita Hayworth (1918–1987)

Portrait of Dorothy Lamour (1914–1996)

Portrait of Ida Lupino (1918–1995)

Portrait of Ginger Rogers (1911–1995)

Portrait of Rosalind Russell (1907–1976)

Portrait Norma Shearer (1902–1983)

Portrait of Barbara Stanwyck (1907–1990)

Portrait Shirley Temple (1928–2014)

Portrait of Lana Turner (1921–1995)

Portrait of Loretta Young (1913–2000)

The impressive lineup of these eminent actresses added to the splendour of the event.

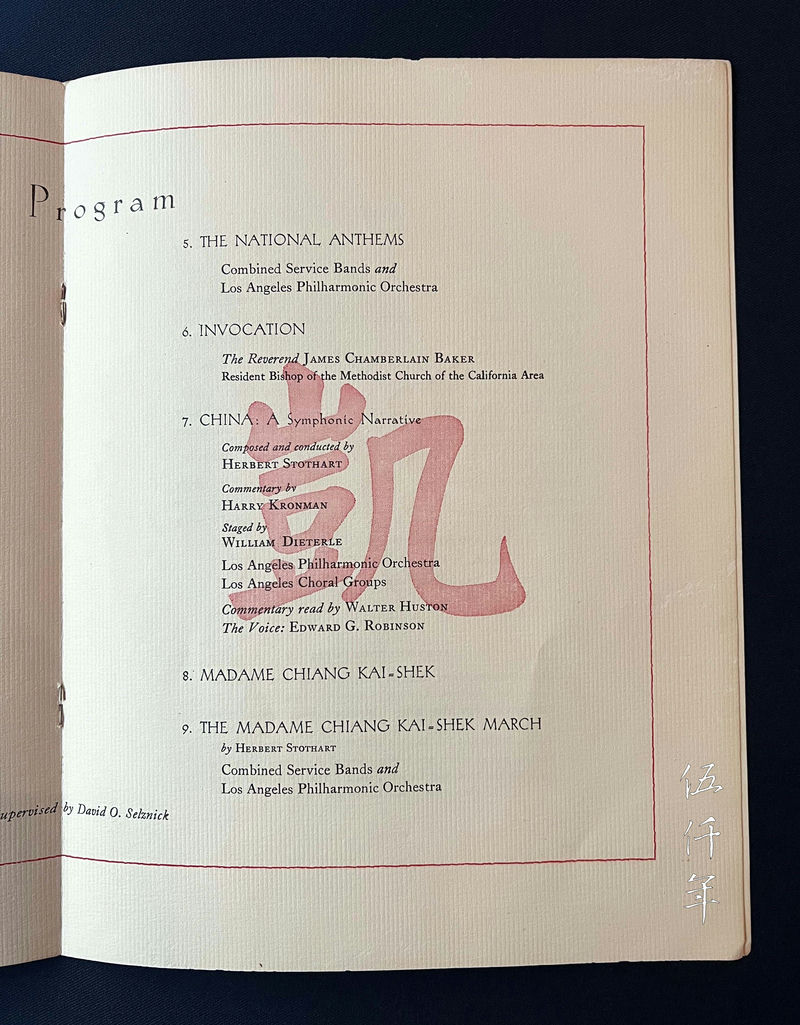

Fourth page inside the Programme

The fifth scene is The National Anthems, performed by the Combined Service Bands and the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra.

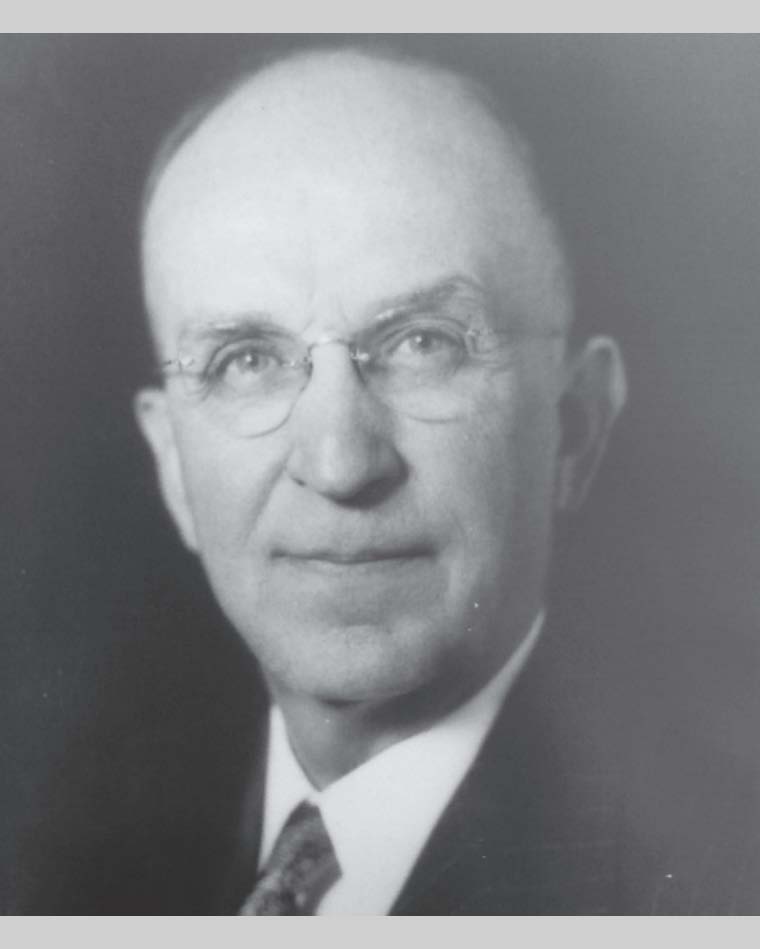

Portrait of Bishop James Chamberlain Baker

The sixth scene is Invocation, conducted by Bishop James Chamberlain Baker (1879–1969) of the Methodist Church, as Madame Chiang was a member of this denomination.

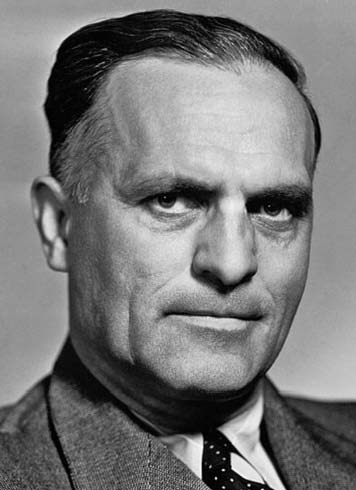

Portrait of Herbert Stothart

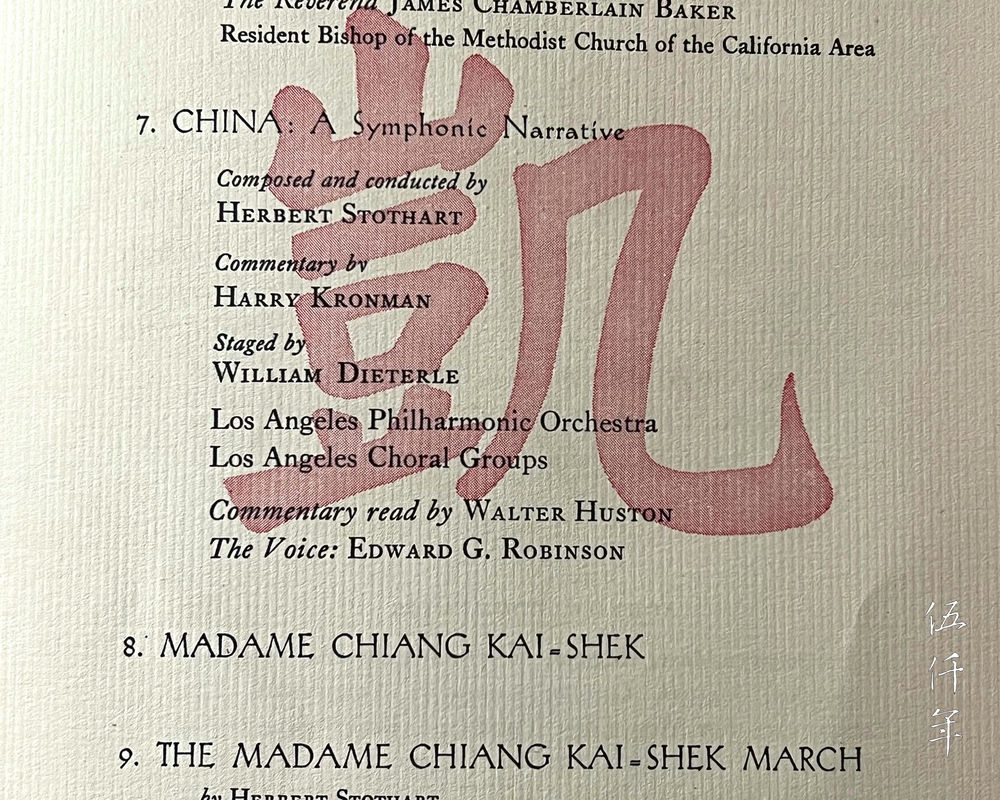

The seventh scene is China: A Symphonic Narrative, composed and conducted by Herbert Stothart (1885-1949), performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra with the participation of Los Angeles Choral Groups.

Seventh scene of China-A Symphonic Narrative printed on the middle part of fourth page inside the Programme

The eighth scene is Madame Chiang Kai-Shek. Madame Chiang delivered a forty-minute speech, making this the longest speech of her visit to the United States that year. Hollywood is a significant cultural hub in the United States, and the power of film dissemination is immense. As the event was produced with Madame Chiang’s address as highlight, she therefore delivered a particularly lengthy speech. The Los Angeles Times complimented Madame Chiang’s speech on the 4th, saying that “It was a voice that must be heard”.

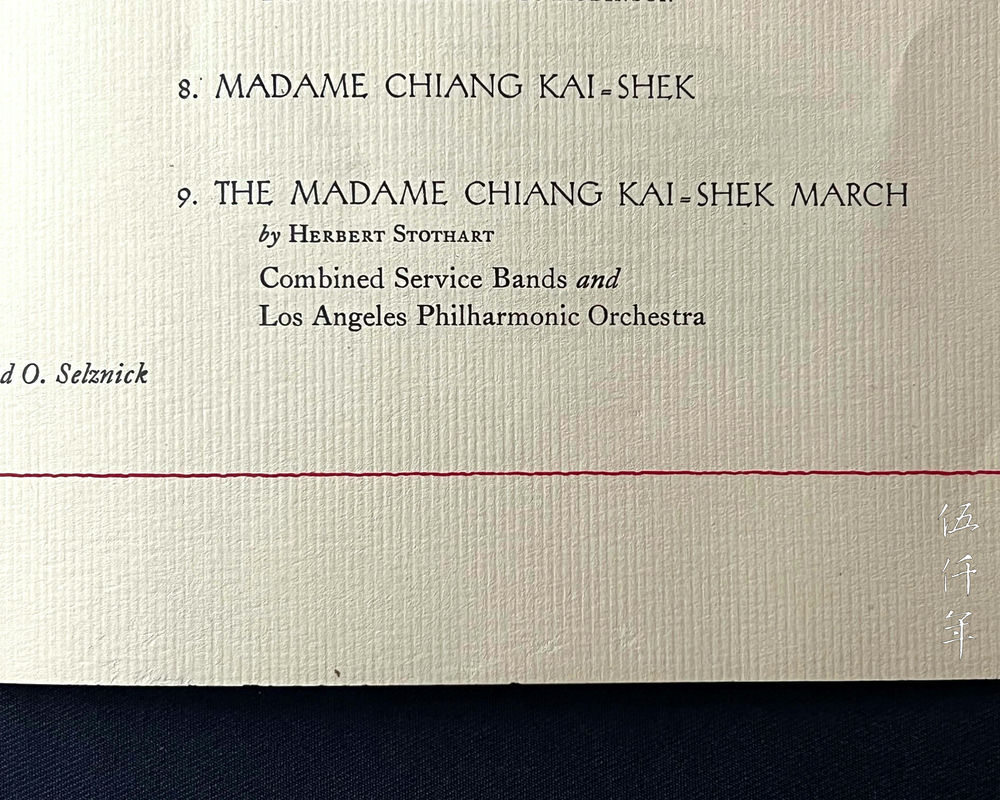

Ninth scene of The Madame Chiang Kai-shek March printed on the lower part of fourth page inside the Programme

The ninth scene is The Madame Chiang Kai-Shek March, performed by the Combined Service Bands and the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra.

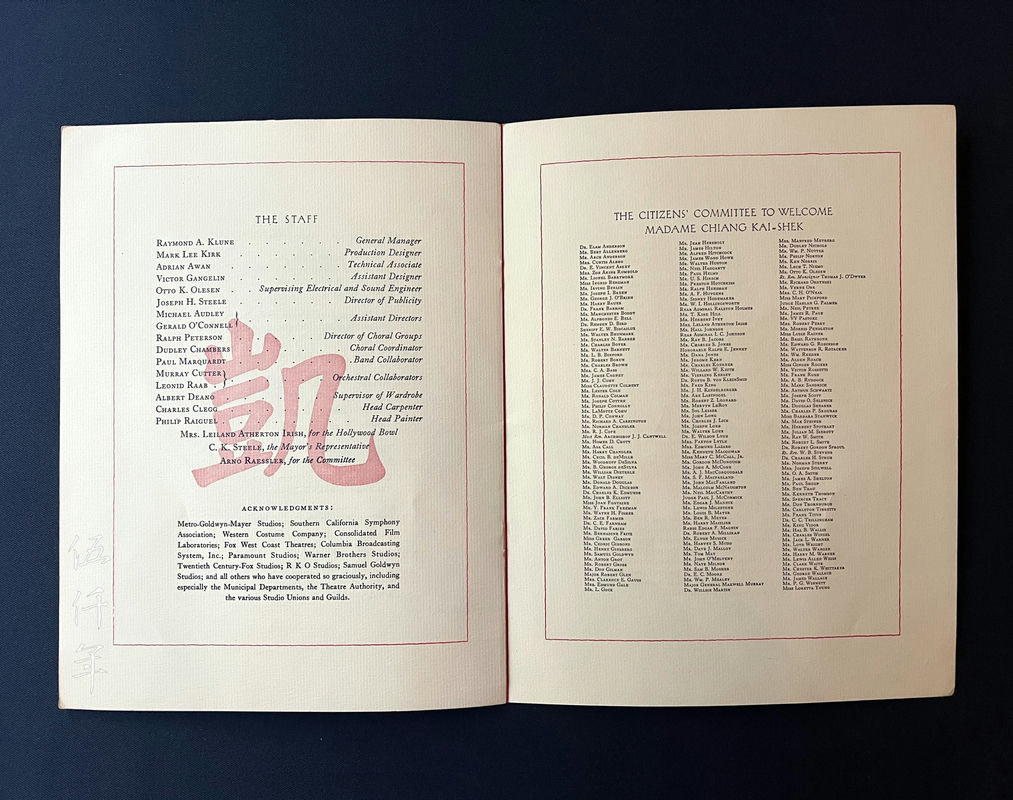

Fifth and Sixth page inside the Programme

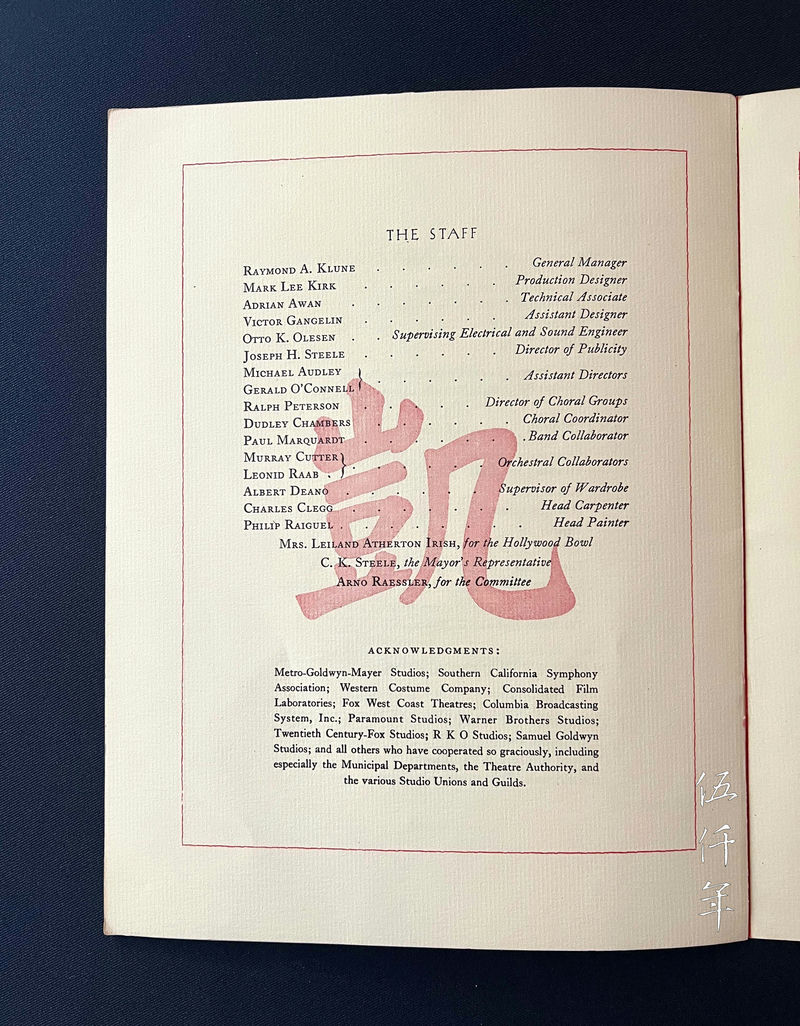

Name lists of staff and acknowledgements on fifth page inside the Programme

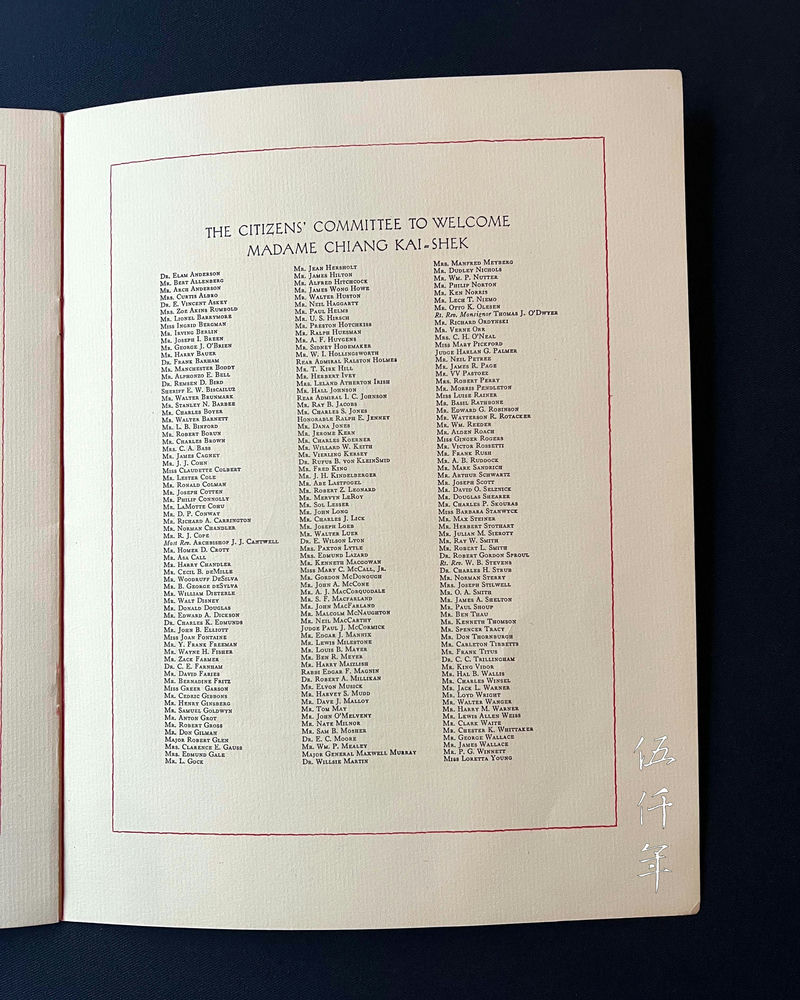

Name list of Citizen’s Committee to Welcome Madame Chiang Kai-shek

On the fifth page is a list of staff supervisors and acknowledgements. On the sixth page is a member list of The Citizens’ Committee to Welcome Madame Chiang Kai-shek, consisting of 204 prominent individuals, including Walt Disney (1910–1966), Alfred Hitchcock (1899–1980), and Harry Warner (1881–1958).

Portrait of Walt Disney

Portrait of Alfred Hitchcock

Portrait of Harry Warner

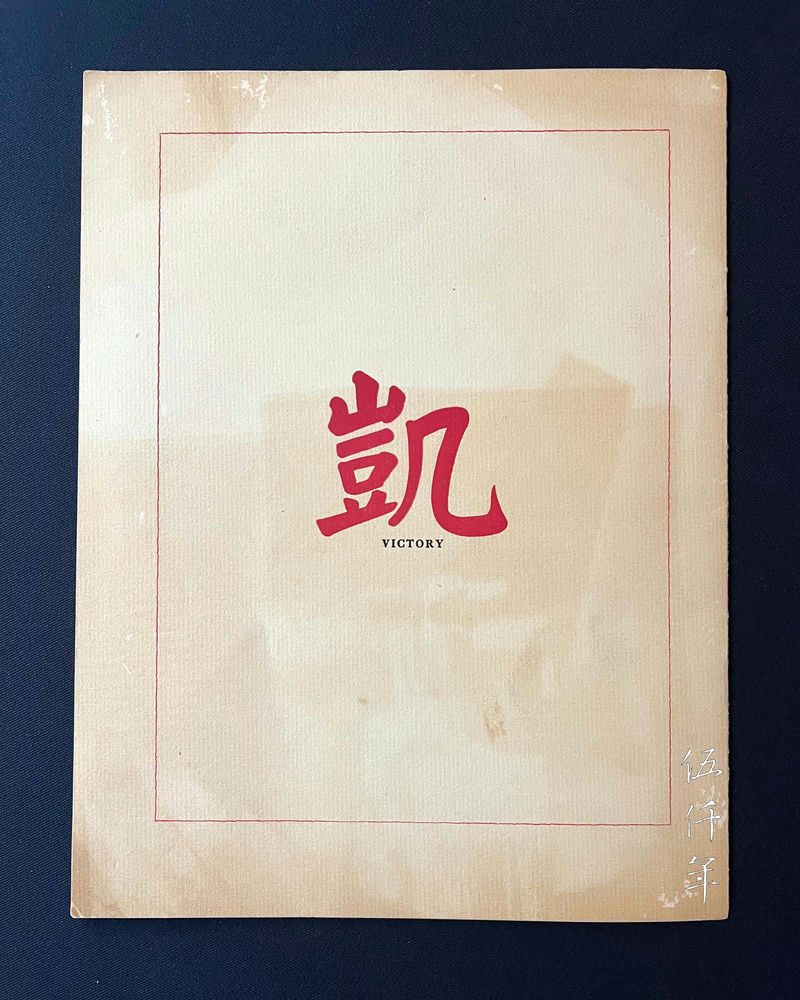

The back of the booklet features the Chinese character k’ai (凱) in red, with the English meaning “Victory” below. The character k’ai (凱) was also used as an emblem for the event, expressing hope and anticipation for the final victory in the Chinese War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression.

Back of Programme with the Chinese character k’ai (凱) meaning victory

Detail of the Chinese character k’ai (凱) on back of Programme

Madame Chiang’s visit to the United States showcased her talent and style, captivating the politicians as well as the general public. She persuaded public opinion and dispelled prejudices against the Chinese. Furthermore, various sectors contributed funds to assist China's war effort. Her visit was especially helpful to the long-term fundraising for aid by the United China Relief organization which was established in New York in 1941.

According to the articles published in the “Kuo-min Yat-po Newspaper ” (美洲國民日報) in 1943, Madame Chiang received significant donations on her visits to American cities. The amounts raised in the following four cities are:

|

|

USD |

Chinese Yuan or “Fa Bi” |

|

Boston |

88,000 |

310,000 |

|

Chicago |

66,920 |

200,000 |

|

San Francisco |

12,666 |

606,400 |

|

Los Angeles |

5,943 |

504,500 |

|

Total |

173,529 |

1,620,900 (USD 81,045) |

The currency exchange rate of Chinese Yuan to US dollar was around 1 USD to 20 Chinese Yuan in 1943. The total amount raised in US dollars and Chinese Yuan was the equivalent of USD 254,574. After adjusting for inflation, this amount would be equivalent approximately to USD 4,529,195.20 today. These figures are indicative of the larger picture.

Since the United States declared war on Japan on 8 December 1942, the United Stated signed the Treaty Between China and the United States for Relinquishment of Extraterritorial Rights in China and the Regulation of Related Matters, also known as the Sino-American New Equal Treaty on 11 January 1943. This treaty abolished the unequal treaties inherited from the Ch’ing dynasty. However, regarding domestic policy, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 which prohibited Chinese nationals from working or immigrating to the United States, remained intact and in effect. After Madame Chiang addressed the United States Congress in 1943, public opinion began to change. On 12 March of the same year, the American political figure Norman Thomas (1884-1968) wrote an article in the paper The Call with the title, Events Proving Walls of Racial Separation May Yet be Torn Down. The article said:

“Madame Chiang's success in capturing American friendship argues that walls of racial separation are not so absolute that they cannot be broken down. Now is the time to capitalize her popularity and China's by vigorous insistence on the repeal of the Asiatic exclusion laws, which are a wholly unnecessary insult to Asiatic peoples and an irritant dangerous to future peace. The simplest thing would be to put Asiatic immigration on the e same basis as Europeans. That basis is not ideal but it is immediately practical; it would remove an insult, and at the same time it would effectively prevent any mass immigration to America from Asia.”

Madame Chiang's visit to the United States accelerated the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act. On 17 December 1943, the U.S. Congress finally passed the Repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act, also known as the Magnuson Act.

The documentary film On the Occasion of the Address of Madame Chiang Kai-Shek to the People of Los Angeles was fortuitously located a few months ago in the United States. It was a thrilling discovery since it had been shelved in obscurity for eighty years. However, watching Madame Chiang’s address brings mixed emotions and bitter feelings. Although China was victorious in the war, mainland China soon fell to the communists, from which it is still unable to recover after decades of sufferings. A free and democratic China survives only in the far corner of Taiwan. One reasons that Madame Chiang’s account of the tribulations during the war and the building of the nation can serve to inspire our fellow countrymen, to overcome infinite adversities to rebuild China once more. The documentary film and the full text of her address are respectfully presented here, to examine the past, to invigorate the present, not least to undertake her counsel: Free China Shall Rise Again (我將再起).

Newspaper illustration of Madame Chiang Kai-shek as the Joan of Arc of China

Address of Madame Chiang Kai-shek at Hollywood Bowl, Hollywood, California, 4 April 1943

“All experiences, happy or tragic, leave their impress, and consciously or otherwise influence our subsequent thinking and attitude of mind.

As the seventh year of China’s resistance against Japanese aggression approaches, I shall sketch a few of the incidents most vividly incused on my mind, and, insofar as it is humanly possible, adopt a detached and objective view in examining the processes of mind which led me to certain convictions. For, from them, perhaps, you may gain an insight into the lives and motives of a people who for many long years have endured the brutalities of being invaded. Time does not permit me to give you a balanced or comprehensive account of the war. I shall leave that task to the historians.

I hesitated to talk to you about war in China lest it should appear that my intent is to over-emphasize the suffering of my people.

On further thought I believe you would understand that the purpose animating me lies in essaying in my own mind, as well as in yours, to profit by the lessons which these years should teach us.

I shall not encumber you with the history of the perfidy of the Japanese. We can well find its counterpart and parallel in the talks between the Kurusu mission and the State Department just before the attack on Pearl Harbor, for they have a flavor familiarly reminiscent of those in the days following the Lukouchiao Incident when Japan feigned negotiations with the Chinese Government while massing her troops for total invasion.

At the beginning of war in 1937, my duties as Secretary-General of the Chinese Air Force kept me chiefy engaged in air activities. We had just reorganized the air force and the total number of planes we had was pitifully and incredibly scanty-less than 300. Of these, something short of a hundred were fighters and bombers. The Japanese, on the other hand, had approximately 5000 fighting planes.

On the very first day of air combat our young cadets shot down 14 enemy bombers. We ourselves on that day sustained no irreparable loss, for although our planes were riddled with bullets, they still could fly. For three consecutive days enemy planes attacked the same objective—the Hangchow Aviation School—and each time our airmen, flying archaic Hawk II’s and a few Hawk III’s, matched and outfought the enemy, shooting down a considerable number.

The Japanese were completely bewildered and even went so far as to say that we had some secret beam which enabled our young pilots, many of whom were yet undergoing training, successfully to shoot down their bombers. At first we too, could not believe that the reports were entirely accurate. The charred remains of the enemy planes, however, bore witness to the veracity of the reports.

As time passed, fewer and fewer combat planes remained to us, for most of the planes ordered before the war were not due for many months. The lack of replacements for our lost planes was further accentuated by the paucity of spare parts, and nowhere on the horizon shone there a ray of hope to mollify and alleviate our dire difficulties. Problem after problem stalked in nightmare procession. The Nanking aerodrome did not have a runway sufficiently solid to allow the take-off of the heavy Martin bombers which eventually arrived and were then being assembled. A new runway had to be made. Where was the material to be found at such short notice, especially with the nation’s transportation geared to more pressing tasks? A solution evolved. I asked myself to what more appropriate use in such an emergency could the material on the excellent roads leading to Dr. Sun’s mausoleum be put than this? So we decided to tear up those roads and take that material for the runway. But hardly was the first problem solved before another interlinked difficulty confronted us. Where could we find the labor?

I thought of the thousands of refugees who were daily streaming into Nanking and undertook to appeal to them for help. Every able-bodied man responded. As the enemy planes bombed the city every day during daylight hours, the refugees worked by night—tens of thousands of them by the dim light of kerosene lamps. Through concerted and unflagging toil the heavy runway was completed in record time, thanks to the energy, persistence and patriotism of the refugees who gave their time and labor without stint and without murmur; asking in return no remuneration, no manifest recognition of their service.

The need for planes became ever more pressing and the devastation and destruction wrought by the enemy over the whole countryside made it imperative that we had to resort to measures which may seem ludicrous to you. Yet what else could we do? Every effort must be made, every means must be employed to equal the high morale of the army and the people.

The constant cry of the young cadets was to give them anything which could fly and so we put bomb racks on the Hawk II’s and III’s which from that time on served both as bombers and pursuits. We also equipped the primary training planes—the Fleets—with bomb racks. But, alas, the latter were found to be too fragile and too slow to be effective. To those lads, however, any machine which could go soaring into the sky meant snatching that much edge off the vast initial advantage held by the enemy.

We husbanded our small air force with the utmost care, and each mission was carefully planned so that for the least expenditure could be achieved the greatest result. It was heart-breaking to send the boys up to defend our Capital from the skies or out on bombing missions, for the odds against them were so tremendous that each time many failed to come back. For many months I had worked with the boys and had learned to know them personally. They trusted me because they knew that what I had been telling them were my honest convictions: that we must fight for principles; that every man was to be judged on his own merits; that no favoritism was to be shown to anyone, but that absolute impartiality in spirit and in treatment was to prevail throughout the whole air force.

Through my experience of that period I have come to be reaffirmed in the belief that any service can be built up when the directing policy is based on impartiality and fairness and when the ranks know that reward and punishment are meted out according to their just deserts.

Meanwhile the Japanese had concentrated their naval power at Woosung and under its protection landed an ever-increasing number of troops in the eastern part of the International Settlement of Shanghai. Thus, whilst the enemy had the advantage of the International Settlement as their base for attack, our troops had the disadvantage of the International Settlement, for we were not allowed even to use it as a thoroughfare. Our soldiers, with totally inadequate mechanized equipment and with absolutely no air protection, fought on the outskirts of Shanghai literally for every inch of land that the Japanese gained through the combined use of heavy artillery, naval guns and incessant bombing. And the Japanese average gain was less than a mile a day.

On that front for three months our troops fought with the fury of the inspired whilst the Japanese military moaned that China was not playing fair because her troops did not know when they were defeated. The spirit of our soldiers shone with steadfast splendor, and their selflessness instilled courage and determination in our sorely tried and harassed people. It was all that the High Command could do to hold back the troops in their trenches. They wanted to combat the enemy at close quarters; so clear was their realization of the principles at stake, and so great their indignation that good faith could be broken by the mere whim of those who knew only desecration.

Wherever the Generalissimo went to hold conferences with his officers at the front I accompanied him. The trips held dangers even when made in the dead of night, for rail traffic was disrupted by constant bombing and congested with troop movements and on the highways, road lights were turned off and all motorcar head-lights dimmed by black cloth lest enemy planes should spot us.

Once we arrived in Soochow just when some troop trains had pulled in. The station was a shambles from repeated bombings but the railway officials, tottering with weariness and lack of sleep, stuck doggedly to their work. Stretcher-bearers worked like wordless automatons trying to clear the station platform of the wounded while more and more wounded were unloaded. Clammy, sticky blood clung like glue to our thick walking shoes while more blood seeped through the soles; still more blood spattered over us as we stumbled through the closely packed station. The wounded were huddled in every inch of available space—young men who a few hours before were full of vitality and vigor and who now were slowly being drained of life itself.

Only an occasional gasp of pain echoed across the roofless station; most of the sufferers bore their anguish in stoic silence. One young lad, stretching out his hand, tugged at my coat as I passed him, murmuring: ‘Water, water.’ I sent an aide-de-camp to get some water. Immediately a medical officer advised me that in the case of stomach wounds no water should be given. I shall never forget the look on the young lad’s face as I sorrowfully shook my head and told him that for his own good I could do nothing for him. That face so young, almost that of a child, twitching with the excruciating pain made by the gaping wound, how can I ever forget? Why should the Almighty select those so young, so innocent, so untried, to be offered as sacrament on the communion table of national honor? Have they, perhaps, sinned against the tenets of God? Or is theirs the vicarious lot of retributive justice?

It is true that life, if it is of any worth, must have as its constant companion, Honor. Death occurs as the final culmination inevitable in the processes of life. And indeed it falls not to all men to share the privilege with the crusaders of truth to breathe their last while in line of duty, and to have the benediction of knowing during their last conscious moments that they are dying in the upholding of ideals more meaningful than life. War is cruel, terrible and revolting and should never be permitted to recur. We who have experienced it at its worst cannot extol nor glorify it, but we take comfort that the last moments of our youths in making the supreme sacrifice are illuminated by the lambent glory of righteousness and justice while the youths of the enemy are decimated without solace that they are dying in order that civilization may survive.

To return. As the enemy landed increasingly long-ranged guns and heavy artillery, the time came when the Central Government decided that all civilians should evacuate Nanking. Hundreds of thousands of people who hitherto had made the capital their home had to take what they could carry and leave the rest to be consumed by fire in adopting the strategy of what is now commonly called the ‘scorched earth policy.’ In no wise did we want the enemy to have any more advantage than we could help.

The trees which we had planted so proudly 10 years before in our high hopes to make Nanking truly the ‘capital beautiful’ had to be hewn down so that the artillery could have the necessary unobstructed view. To have watched the saplings gradually grow year by year into sturdy trees and finally to witness their tops cut off was like seeing live pets killed before our very eyes.

The Generalissimo and I were amongst the last of the officials to leave Nanking. Before we left we took steps for the removal of the irreplaceable and priceless treasures of the National Museum of Art to quarters safe from enemy looting. Later I went outside of the city wall for a final look at the now empty buildings of the schools for the children of the revolution. Here and there in the fields beyond the campus I saw thatched huts not yet devoured by flames, some outside walls still intact, and hanging on them strings of dried beans, peas, lentils and cobs of corn. They were the pick of the harvest and had been carefully saved as seeds for the next crop. But for these humble folks, who for generations had lived, loved and had their being on the soil, there was now no next crop, not for many years, anyway, not until after victory is won.

During such moments I wondered whether the mania of the bloodthirsty is ever slaked by the display constantly before their eyes of the human suffering and havoc they have wrought. Are they such diabolic Lucifers that they can only revel in human misery? Well might I have such musings, for the world now knows to what extent the Japanese military carried their calculated cruelties after they occupied Nanking and other areas, how they plundered and stripped the terrified populace of all means of livelihood, molested our women and rounded up all able-bodied men, tied them together like animals, forced them to dig their own graves, and finally kicked them in and buried them alive.

Settled temporarily in Hankow, we realized that the war would be long and hard, and that to sustain a defensive war of the magnitude and length we had in mind, Hankow was merely a stepping-off place to enable us to take stock of our weaknesses and reassess our strength in making preparations for the future. In equipment the enemy undoubtedly outstripped us in every way, for theirs was a modern army with all auxiliary services complete, including mechanized units, trained engineer corps, and fully equipped medical contingents, in addition to a powerful navy and an equally powerful air force.

And what did China have? We had no navy to speak of, only an embryo air force and an infantry equipped mainly with rifles, machine guns and outmoded artillery pieces. But we had manpower, which willingly volunteered its flesh and blood. We had fighting spirit, for we knew we were struggling for justice and righteousness, and also, we had the advantages of time and space.

It was our intention and strategy to make the enemy pay, and pay dearly, for every inch of land they wrested from us, so that in time we could wear them out, provided that the will to win could withstand the onslaught of steel and high explosives.

China’s long-continued resistance in the face of formidable difficulties proved that our envisionment of the situation, both psychological and military, was correct. To those skeptics who sneered at China’s ‘magnetic strategy’ I should like to ask: What other people in the modern world has endured the agonies of war for so long and so bravely, held so tenaciously and so staunchly to the defense of principles as the Chinese people? And in the face of such odds in fighting equipment?

Of these same skeptics, I should also like to ask: Given the same conditions, what would they have done, in our position? What could they have done?

I should like to reiterate here that we have been fighting not only for our homes and hearts; we have been fighting for the upholding of pledges and principles because the violation of one pledge means the breaking of the whole chain of international decency and honor.

During those Hankow days, the Generalissimo and I were constantly making trips to the various fronts. The ever-recurring spectacle of the hundreds of thousands of our well-to-do countrymen reduced to being refugees, fleeing on the roads over the countryside, being bombed and machine-gunned by enemy planes, and of the thousands of dead on the roadsides awaiting burial, are ghastly memories impossible to forget. When will the ghosts of our bombed cities, ruined villages, and myriads of men, women and little children murdered in cold blood be laid?

Meanwhile there was work to be done for the living. As war continued, women’s volunteer organizations sprang up all over the country. Systematic co-ordination, however, was lacking, and as a result, duplication of work and confusion prevailed. At a conference called in the hills of Kuling, 50 women leaders representing every section of the country came together. During those 10 days of the meeting we laid the foundations of the National Women's Advisory Council which all agrered should function as the supreme body in directing women's war efforts.

“

We established various departments to meet war emergencies without interfering with existing organizations, but by supplementing and co-ordinating local efforts. The training of girls and women to work amongst the wounded, the refugees, and as liaison between the people and the army, the care of the war orphans, and the increase of production, all received the consideration they deserve.

The response to this movement on the part of women throughout the country was electric. Branch associations mushroomed overnight. Differences of opinion were freely aired and hotly contested, but the final decisions of the Women's Advisory Council ruled. From this experience I am convinced that women can work together, they can, they will, and they must—women of every creed and belief, and yes, of every nationality—provided the cause is big enough, and the challenge worth accepting.

A few months later the Central Government issued hurried orders for the evacuation of Hankow. I had gone to the boat to bid good-by to several hundred of the girls whom I had helped to train for war work. How I hoped and prayed that they would reach their destination, for just the day before a boatload of refugees, including many of our war orphans, was bombed and all perished. As I was walking home I noticed that over the gutters in the streets there still remained thick slabs of iron grates. Would they not be used by the enemy to be made into bombs to kill more of our people? I mentioned this to the Generalissimo and he issued orders that the metal should be taken up and thrown into the river.

The Generalissimo and I took the last plane which left the night before Hankow was occupied by the enemy.

Chungking, wartime capital, now became the center of activity. The same difficulties which obtained at Hankow followed us there. Even the government organizations had a hard time trying to find quarters, for all of a sudden, millions of refugees poured into this district from the Hankow area. But there was one difference; we had already sustained the first impact of war, and the people had become accustomed to makeshifts in living.

Hardly had we arrived, however, before the enemy air force started their bombing and strafing again, hoping thus to break down the morale of our resistance. For several years during the clear season, whenever the city was not enveloped in opaque fog, we were constantly subject to overhead attacks. In fact, Chungking and its vicinity never had a respite until the famous Flying Tigers grappled with the air marauders and fought them off. But, alas, there were not enough Tigers to patrol the vast skies over China, nor enough to give even a little overhead protection to our valiant armies spread out in the nine war zones. Our Chinese Air Force, as time went on, dwindled, for although Russia supplied us with some planes, the need was ever greater than what was obtained. But wherever we could, we made desperate raids over the enemy's supply bases. For the rest, we had to be content with training pilots in the hopes that some day planes would be forthcoming.

Anyone who has an idea of the topography of Chungking would understand the heart-breaking hardships our people had to endure. The city itself is situated on a tongue of land at the juncture of two rivers, the Chialing and the Yangtze. Steep stone steps laced their ways up and down the hillsides and the old houses were built in such a way that there was only one entrance. Oftentimes when a bomb exploded and cut off the one entrance the householders would be trapped without any means of egress. Whole sections of the city were turned into shambles by a few bombs, as the houses were so closely packed together that one incendiary bomb could set off a whole block into flames. We knew days when it was impossible to obtain coffins as the toll of death mounted.

In time, all the business section of the city was demolished, so that it was possible to stand in the midst of the room and get an unobstructed view of the rivers on both sides. It is to the credit of the resurgent spirit of our people that they were not intimidated, for after each bombing, scarcely had the air raid siren trailed off its last echo before the surviving householders returned to their burnt shops and homes and began to salvage whatever they could. A few days later, temporary shacks and buildings would make their appearances on the old sites.

Some days the raids were so close and numerous that no one had time to prepare food. Hours were wasted in the dugout; valuable hours needed for work and rest. But moonlight nights were the worst, for the marauding planes, timed with devilish cunning, came in successive waves. Terrible tiredness permeated every nerve and bone so that it was preferable to risk being bombed to death than seek safety.

But we knew that the enemy was trying to break our morale through sheer physical exhaustion. We were therefore inflexible in our determination not to give in. No greater tribute could be paid to our sorely tried people than this—that in all their suffering never did they complain against their leaders. Never did they falter in the determination that the enemy must be driven from our shores.

They had faith, too, that, in the end, America and the other democratic powers would realize that it was not only for ourselves that we were fighting, and that by continuing to engage the enemy, we were giving time to the democracies to prepare their defenses. Here I should like to say that neither we nor posterity can deprive unerring tribute to the foresight and statesmanship of President Roosevelt when he envisaged to the full the implications and consequences of the struggle of right against might, and took decisive measures to enable America to become the Arsenal of the Democracies. History and posterity will panagerize your President’s unswerving convictions and his moral courage to implement them.

We take pride in the fact that, amid all the stern and never-ending demands of war, we are preparing for a just and permanent peace and for the strenuous world-building that lies before us. You, too, are taking similar steps and, like us, you are determined to contribute your share in the organization of a new and happier social order as you are in prosecuting the war.

We in China through these years of suffering have not turned to indiscriminate, gally hate of the enemy. We shall not abrade the sharp, stony path we must travel before our common victory is won. But we, like you and the other United Nations, shall see to it that the four freedoms will not assume the flaccid statutes of ethical postulates no matter how belated may be the final victory.

We shall not be cozened of an equitable peace. We shall not permit aggression to raise its satanic head and threaten man’s greatest heritage: life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness for all peoples."

Madame Chiang Kai-shek addressing the audience at Hollywood Bowl on 4 April 1943 with the signboard of k’ai (凱) next to her

Related Contents:

Artefacts Related to the Life and Times of Madame Chiang Kai-shek

A Selection of Flying Tigers Artefacts from the Roy Delbyck Collection