Sixty eight years ago, in the 46th year of the Republic 1957, Ch’en Han-kuang (陳含光), the poet from Chiang-tu County who fled mainland China, passed away in Taipei. His calligraphy and paintings are frequently seen in the market, but his poetry works are spotted only occasionally. This is why most art lovers recognize his artworks, and few know of his literary flair.

Mr. Ch’en Chao-k’un is a passionate collector of the literary publications and artworks of Ch’en Han-kuang. He has covered all the categories of books, hanging scrolls, handscrolls and fans. We are privileged to present a short biography he wrote and images of the pieces in his collection for the perusal of our fellow enthusiasts.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

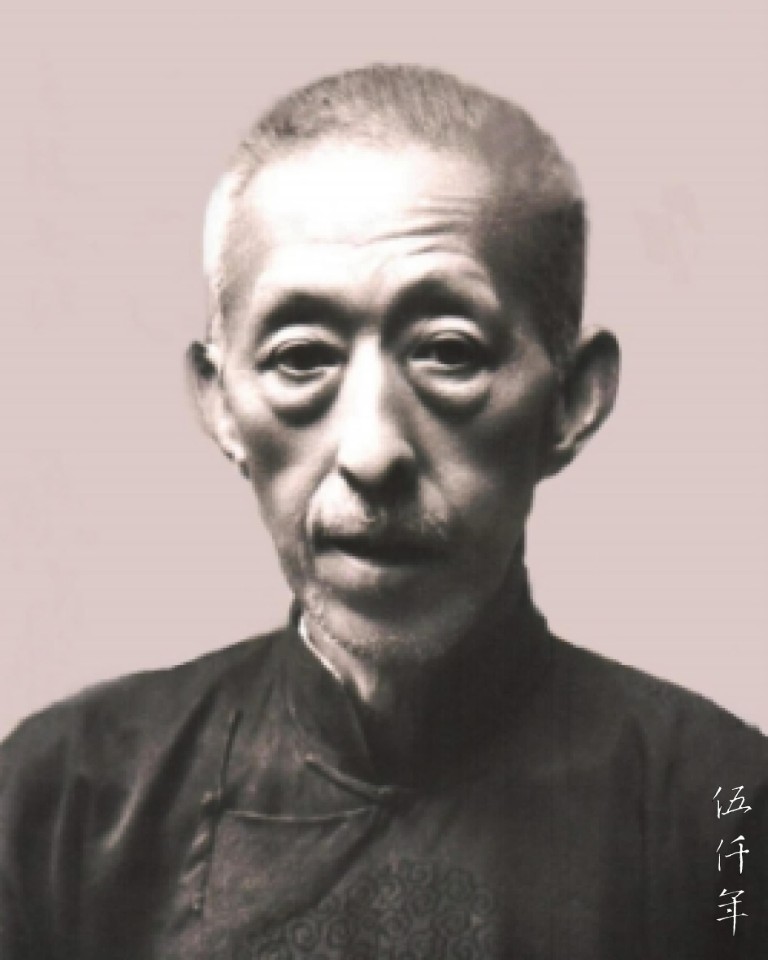

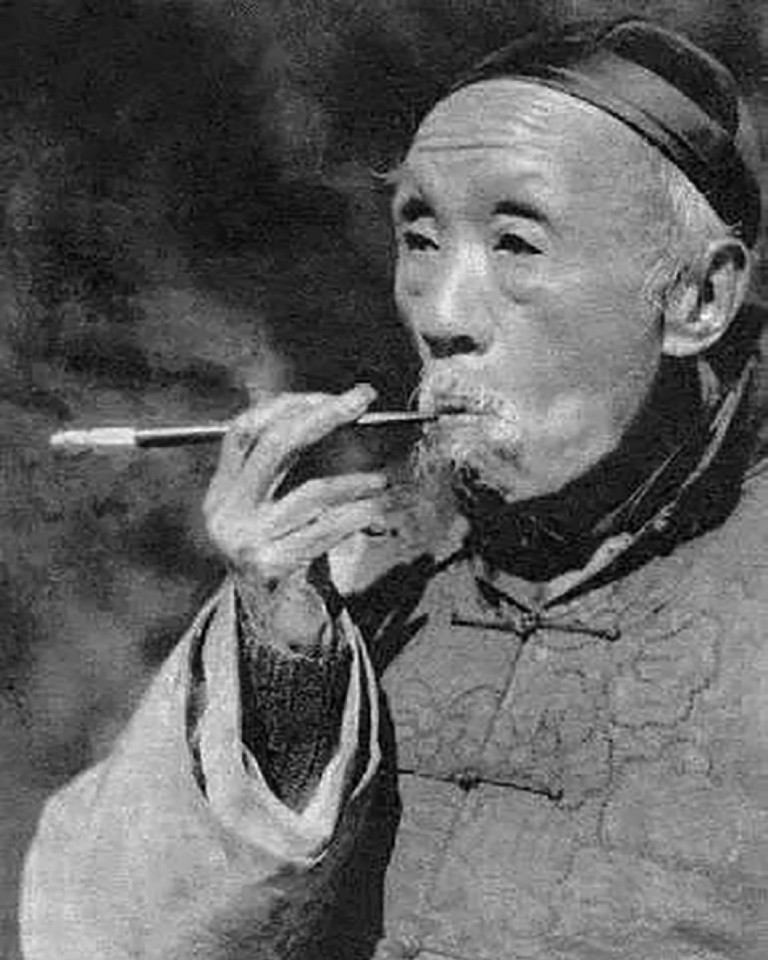

Portrait of Ch’en Han-kuang

In the years shortly before and after 1949 when China fell to the communists, many literati and artists migrated southward from mainland China to Taiwan. Foremost amongst them was Mr. Ch’en Han-kuang (陳含光 1879-1957) of Chiang-tu County (江都), who was widely admired by his contemporaries for both his exceptional integrity and outstanding achievements in prose, poetry, calligraphy and painting.

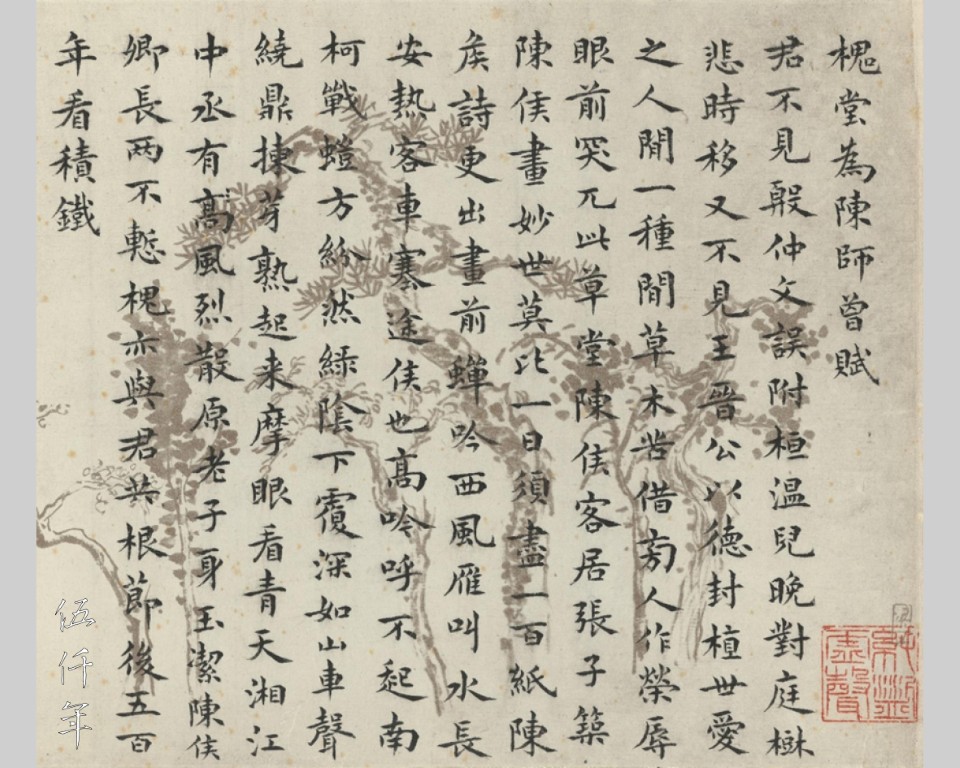

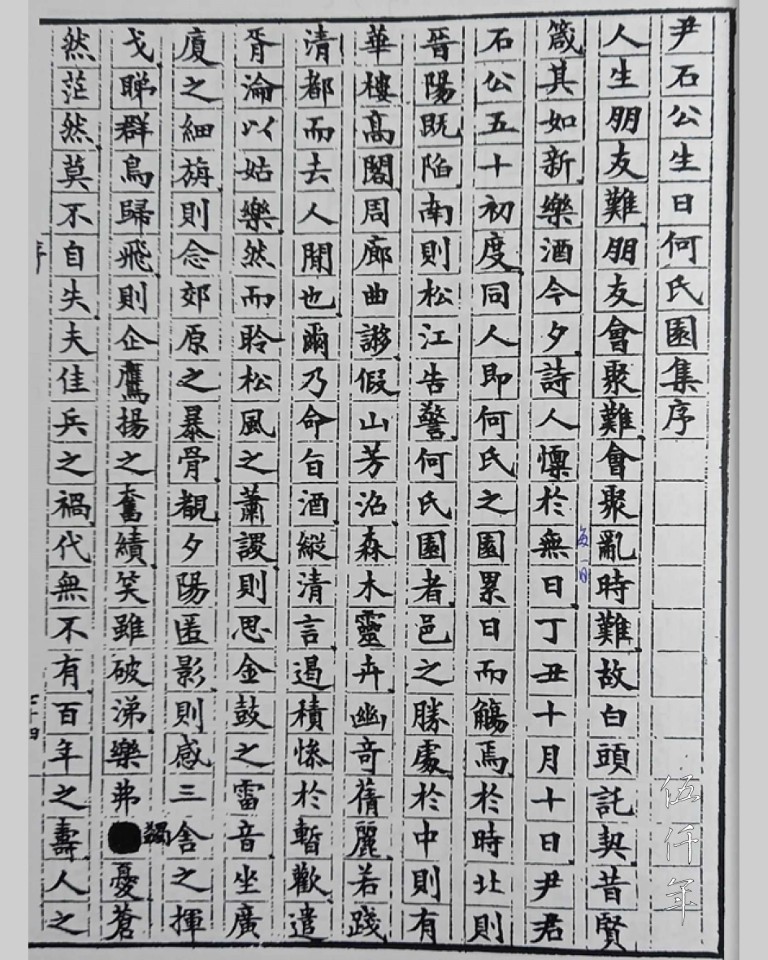

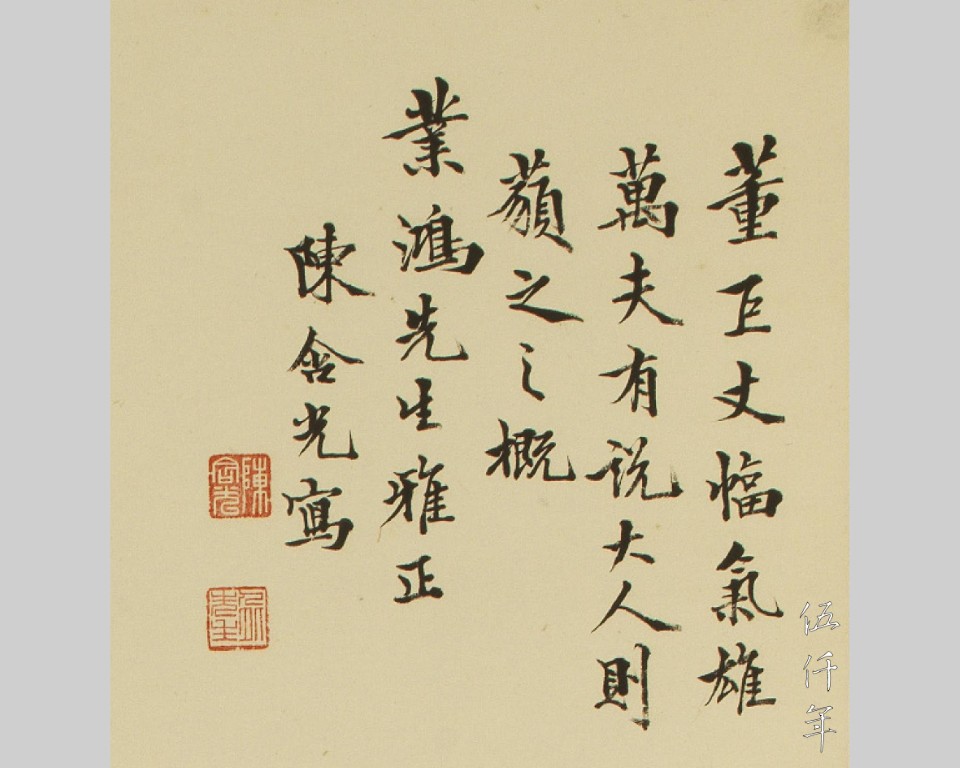

He was famous quite early on, long prominent in mainland China before the fall. After coming to Taiwan for refuge, his reputation grew ever more and became a doyen of the literary community. Unfortunately he is no longer widely recognized today. As a person from another generation, I never have the privilege of meeting him. I once acquired a calligraphy handscroll by him titled Copying the Five Poems by Huai-t’ang Dedicated to Ch’en Shih-ts’eng (書槐堂為陳師曾賦五首), with colophons at the back by various artists who also fled to Taiwan, such as T’ai Ching-nung (臺靜農 1902-1990), Liu T'ai-hsi (劉太希 1898-1989), Chiang Chao-shen (江兆申 1925-1996), Wang Chuang-wei (王壯為 1909-1998), and Wang Chung (汪中 1925-2010). Truly I regret not ever meeting him! Subsequently I became addicted to his works. I have never been timid seeking out his works, and certainly not daunted by the toil of the forage. The more I learn, the more I admire him. Thus I overlook the shortcomings of my writing to compile this modest overview of his life and works, hoping to bring attention and inspiration to the younger generation.

A segment of Copying the Five Poems by Huai-t’ang Dedicated to Ch’en Shih-ts’eng written by Ch’en Han-kuang

Ch’en Han-kuang (陳含光), original name Yen-wei (延韡), tzu I-sun (栘孫), hao Han-kuang (含光), was hailed from a prominent family in Huaiyang (淮揚) of Kiangsu Province (江蘇省). His great-grandfather Ch’en Chung-yün (陳仲雲) and his grandfather Ch’en I (陳彝) both passed the metropolitan examination and attained the degree of chin-shih (進士), earning them the reputation of “The Father and Son Graduates of the Metropolitan Examination, Both Ranked Second Class Number One”, an illustrious story at the time. His grandfather Ch’en I was particularly known for his integrity and outspokenness. As an imperial censor, he stood fearlessly against power and influence and censored the favoured minister of Emperor Mu-tsung (穆宗), earning him praise from the people. His father Ch’en Ch’ung-ch’ing (陳重慶) attained the chü-jen (舉人) degree, having passed the provincial examination in Shun-t’ien (順天), now known as Peking, in I-hai (乙亥) year of the Kuang-hsü (光緒) reign, 1875. He was appointed Salt Administrator of Hupeh Province (湖北鹽法道), and was skilled in poetry and calligraphy.

Ch’en Han-kuang was guided by his family education and studied diligently. He pursued academic work with meticulousness and rigour. He was well versed in philology, and always verified the accuracy of the texts he was going to study. In 1902, aged twenty four, he passed the provincial examination and attained the chü-jen degree. In 1909, aged thirty one, he arrived in Peking to take part in the metropolitan examination. However, upon witnessing the precarious situation of the country, he decided to give up the path of officialdom. He returned to his hometown to study, as well as to practice calligraphy and painting. With the founding of the Republic of China in 1912, he was elected member of the first session of the Kiangsu Provincial Council. In 1914, with the establishment of the Bureau of Historia Ch’ing (清史館), he was appointed assistant editor by its director Chao Erh-hsün (趙爾巽 1844-1927) to compile the Draft History of Ch’ing (清史稿). He came to know other luminaries in Peking such as Shang Yen-ying (商衍瀛 1869-1960), Ch’en Shih-ts’eng (陳師曾 1876-1923), Ho Chen-i (何震彝 1880-1916), Liu Shih-p’ei (劉師培 1884-1919), and Yüan K’o-wen (袁克文 1890-1931).

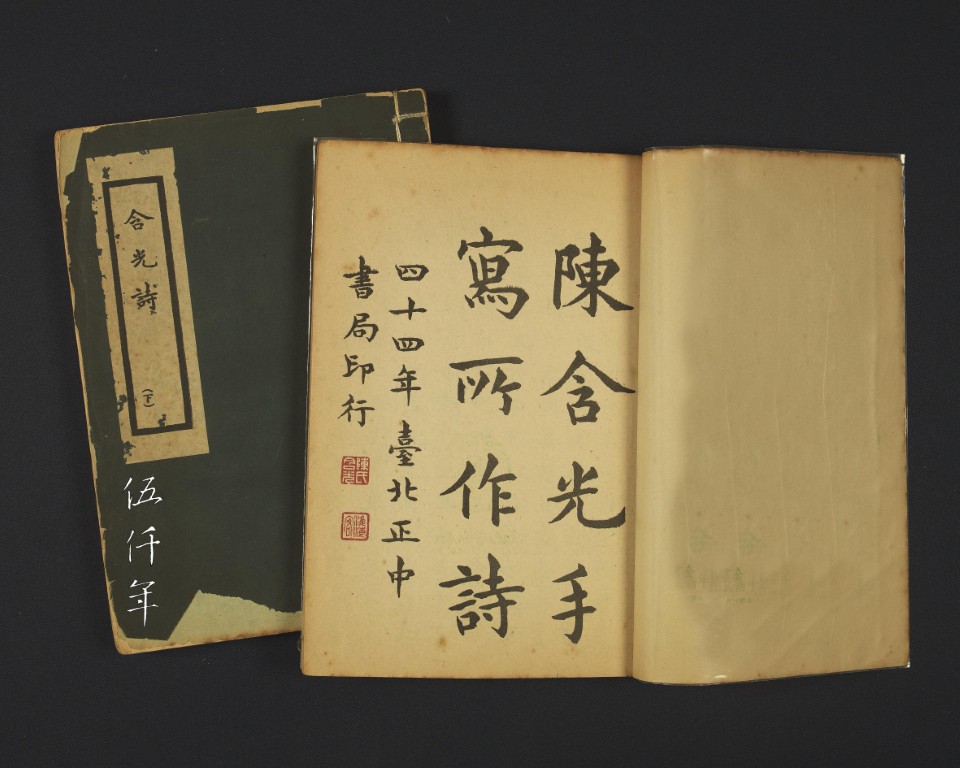

Front cover and inside page of Collected Poems of Han-kuang, Two Volumes

In the 22nd year of the Republic of China 1933, the private Yang-chou School for Classical Studies (揚州國學專修學校) was established, with Chiang T’ai-hua (蔣太華) appointed principal. Ch’en Han-kuang was appointed director and professor of Six Dynasties Literature. During his tenure, Ch’en Han-kuang generously donated many books and taught with enthusiasm and commitment. Despite the financial constraints at the time, where each lecture was only remunerated with a modest amount slightly over one dollar allocated for transportation expenses, he was enthralled in teaching, never missing a class. Those among his students included the t’zu poet Ting Ning (丁寧 1902-1980), the painter Ko Hsiang-lan (戈湘嵐 1904-1964), Minister of the Interior Hong Lan-you (洪蘭友 1900-1958), the poet Chang Pai-ch’eng (張百成), the calligrapher Chang Hua-fu (張華父 1898-1984), who all earned distinction in life.

On 14 December 1937, Japanese troops attacked and entered Yang-chou City (揚州). They burned, killed, plundered and raped. The indomitable woman Keng Ru-ch’eng (耿汝誠) committed suicide by poison to demonstrate her resoluteness. Ch’en Han-kuang’s close friend, the t’zu poet Wang Shu-han (王叔涵), had his home looted bare. Despite this, the Japanese continued to demand more. Wang Shu-han, unable to bear it anymore, vehemently rebuked them and fell under their gunfire. Ch’en Han-kuang’s elderly brother was also threatened by a drunken Japanese soldier who held a sword to his throat. He fell ill from the shock and died shortly afterwards. The Japanese army wanted to establish a self-governing organization to control Yang-chou City, and drew up a list with Ch’en Han-kuang’s name second on the list. At that time, the Japanese commander Amaya repeatedly invited Ch’en Han-kuang to join as a committee member, but he declined citing old age and illness, secluding himself at home. When pressured to provide calligraphy and paintings, he preemptively destroyed his brushes, inkstones and paper to desist. In grief and anger, he wrote articles such as Account of a Witness (再報所親書) and The Biography of the Virtuous and Brave Sixth Sister Keng (貞烈耿六姑傳). Using the pen of a historian, he faithfully recorded the atrocities of the Japanese army. He contrasted the example of Sixth Sister Keng (Keng Ru-ch’eng), who sacrificed herself to uphold her integrity, with the disgraceful behavior of the members of the self-governing organization, who under the pretext of saving the people, sought personal benefits, displaying the enemy’s flags and adopting the enemy’s reign title. Moreover, he climbed up to the Shih Gong Shrine (史公祠) on Meihua Ridge (梅花嶺), in front of the memorial tablet of the Ming dynasty loyalist Shih K’ei-fa (史可法 1601-1645) who fought against the invading Manchus, and composed these passionate words: “I would rather die on the spot than join their ranks, this is an oath in front of the ancients”. In August 1945, with the victory of the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression, he briskly wrote a pair of calligraphy couplets on red paper: “Eight years I laid low, Peace restored in a day”, and pasted them on his front door to celebrate.

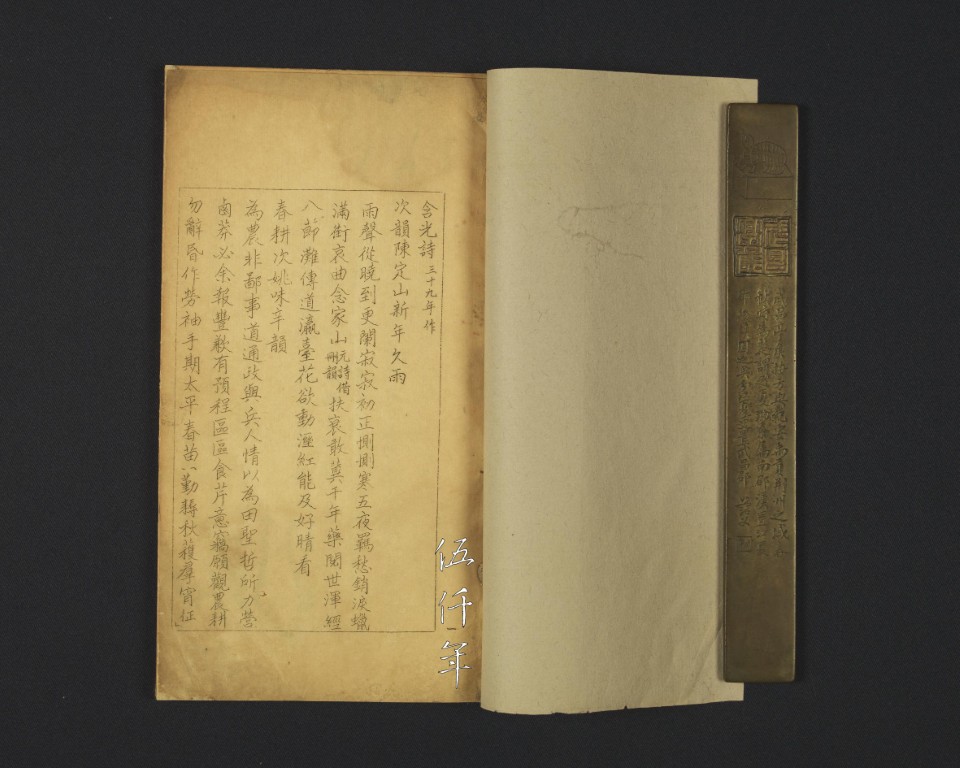

Inside page of Collected Poems of Han-kuang

In February 1948, on Ch’en Han-kuang’s 70th birthday, his friends and students organized a grand celebration in his honour. Liu Yi-cheng (柳貽徵 1880-1956) crafted a pair of calligraphy couplets: “Fine writings excel Wang Yung-fu (汪容甫) in longevity, Worthy calligraphy supplant Wu Jang-chih (吳讓之) in renown”. He compared him to the eminent literati Wang Chung (汪中 1745-1794, tz’u Yung-fu) and Wu Hsi-tsai (吳熙載 1799-1870, tzu Jang-chih) from Yangchou’s past, praising his accomplishments in p’ien-wen (駢文 parallel prose) and calligraphy. The Su-pei Daily News (蘇北日報) dedicated a special edition titled Special Issue on Mr. Ch’en Han-kuang’s 70th Birthday (陳含光先生七十華誕特刊), signifying his venerated position and reputation in Yang-chou. In summer that year, together with his son Ch’en Kang (陳康), they fled to Taiwan. He accepted a teaching position in the Department of Philosophy at the National Taiwan University. Thereafter, he obscured his name and adopted the hao “Han-kuang” (含光) and also used the noms de plume “Huai-hai Visitor” (淮海客) and “Solitary Wanderer” (孤行者).

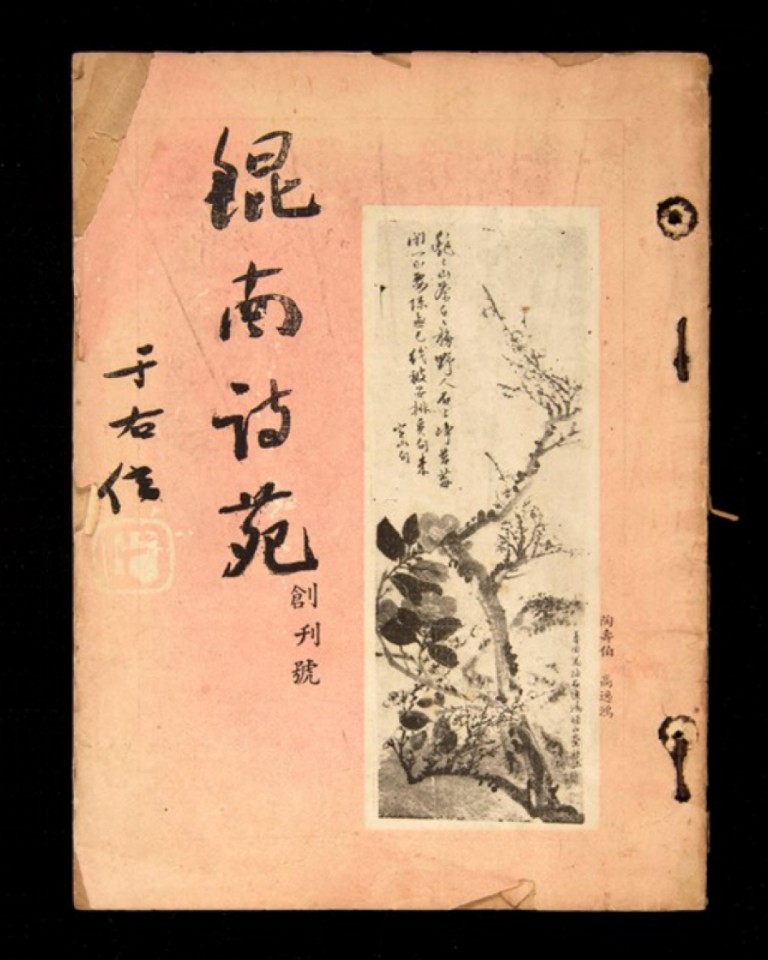

Front cover of first issue of Kung Nan Poetry World. Photograph courtesy National Museum of Taiwan Literature

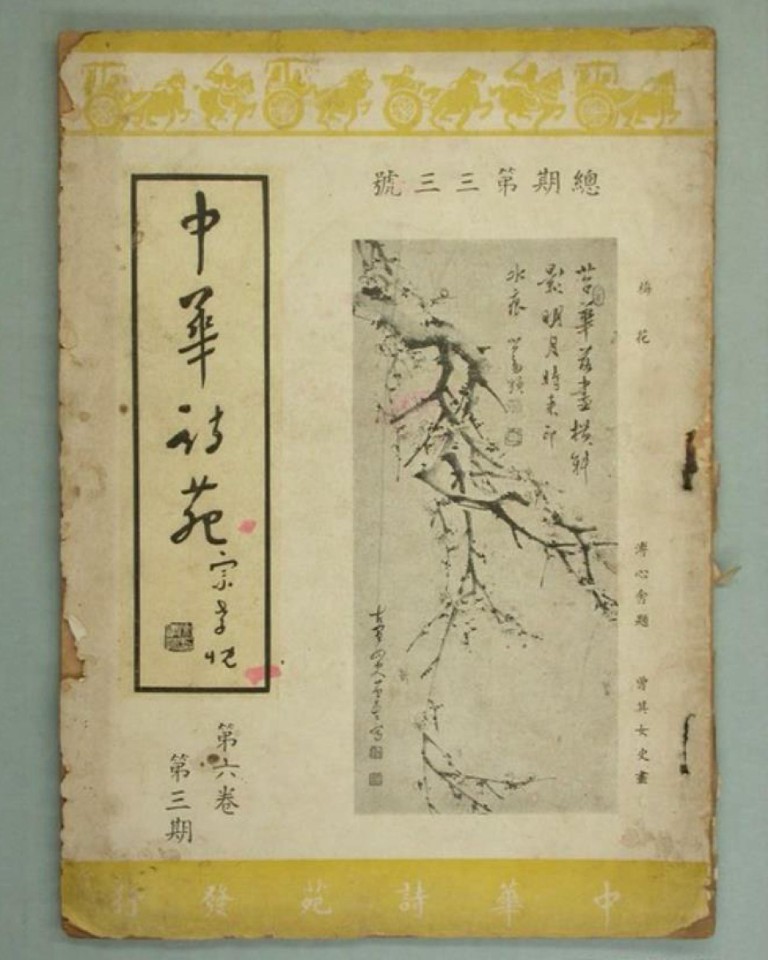

The 33rd issue of The World of Chinese Poetry. Photograph courtesy National Museum of Taiwan History

After coming to Taiwan, Ch’en Han-kuang was active in literary and artistic circles, frequenting poetry gatherings and literary salons. He socialized with other prominent poets such as Yu Yu-jen (于右任 1879-1964), Chang Chao-ch’in (張昭芹 1873-1962), Li Yu-shu (李漁叔 1905-1972), P’eng Ch’un-shih (彭醇士 1896-1976), Ch’en Feng-yüan (陳逢源 1893-1982), Chia Ching-te (賈景德 1880-1960), Hsü Shih-ying (許世英 1872-1964) and Chang Mo-chün (張默君 1884-1965), gifting each other poems back and forth. He was a consultant to journals such as Taiwan Poetry Forum (臺灣詩壇), The World of Chinese Poetry (中華詩苑), Friends of Poems and Essays (詩文之友) and Kun Nan Poetry World (鯤南詩苑). He eagerly published his writings, calligraphy and paintings in these poetry journals. On 9 May 1952, Ch’en Han-kuang held a three day exhibition of his recent landscape paintings at the Social Service Center on Section 1 of Jinan Road in Taipei City. In December 1956, his works Texual Research of New Songs from the Jade Terrace (玉臺新詠考證), Handwritten Poems by Ch’en Han-kuang (陳含光手寫所作詩), and Han-kuang’s Manuscripts of P’ien-wen (含光儷體文稿) earned him the Ministry of Education’s Academic and Literary Award in the 45th year of the Republic of China. Sadly he passed away from illness in March the following year in Taipei.

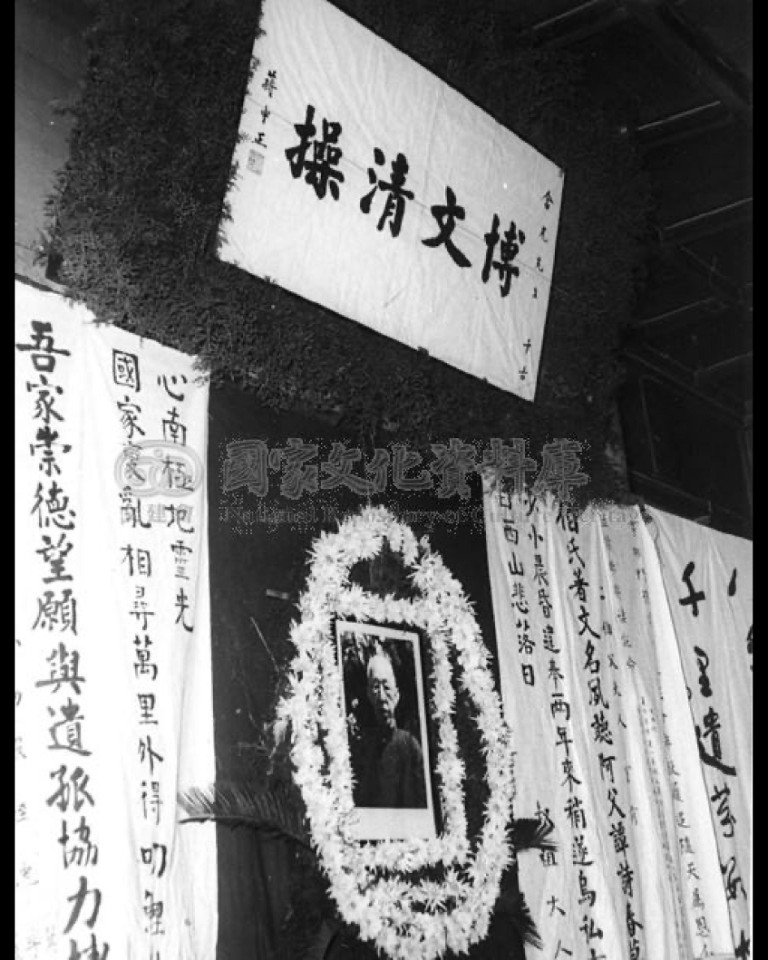

Scene of the funeral of Ch’en Han-kuang. Photograph courtesy Taiwan Cultural Memory Bank

On the day of Ch’en Han-kuang’s funeral, luminaries from all circles came to pay their respects, writing mourning couplets and poems in his honour. Amongst the attendees, only P’u Yu (溥儒 1896-1963)performed the antiquated ritual of “three kneels and nine kowtows”, evidence of the depth of their friendship. Yu Yu-jen (于右任), K’ung Te-ch’eng (孔德成 1920-2008), Tseng Chin-ko (曾今可 1901-1972), Chang Chao-ch’in (張昭芹), Liang Han-ts’ao (梁寒操 1899-1975), and Chia Ching-te (賈景德) decided to privately honour Ch’en Han-kuang with the posthumous name of “Yüan-ching Hsien-sheng” (元靖先生). President Chiang Kai-shek conferred the mourning placard “Erudite Scholarship, Moral Rectitude” (博文清操) and issued an official commendation on 13 July that year.

Ch’en Han-guang was the same age as Yu Yu-jen (于右任). Yu Yu-jen had written many birthday poems for Ch’en, including the lines, “Your poetry, calligraphy, paintings are known as The Three Wonders, So much lesser my writings in comparison to yours”. This was an expression of his deep admiration for the writings of Ch’en Han-kuang.

Portrait of Ch’en San-li

Ch’en Han-kuang was celebrated for his poetry early in life. Wang Kuo-yüan (汪國垣 1887-1966), the author of The Roster of Poets in the Kuang-hsü and Hsüan-t’ung Reigns (光宣詩壇點將錄), listed him as one of the one hundred and eight prominent poets of the time. Ch’en authored several collections of poetry, including Collected Poems of Han-kuang, First Volume (含光詩甲集), Collected Poems of Han-kuang, Second Volume (含光詩乙集) and Drafts of Poems on Taiwan Travel (臺遊詩草). His poetry is not confined to any one style but has a unique character of its own. Yu Yu-jen praised his poetry as “purer than San-yüan” (詩比散原清). This comparison places Ch’en Han-kuang alongside the poet Ch’en San-yüan (陳散原), whose original name was Ch’en San-li (陳三立1853 -1937), a titan of the Poetry Style of the T’ung-chih and Kuang-hsü Reigns (同光體). Ch’en San-yüan was known for his adherence to Sung dynasty poetry while favouring novelty, with his own “unrefined and profound” style. Ch’en Han-kuang was younger than San-yüan by a generation, yet both poets exude a scholarly air and a sense of melancholy in their works. Ch’en Han-kuang’s poetry is comparatively much purer and smoother.

Ch’en Han-kuang believed that the most important quality in poetry was its emotional component. His series of twenty quatrains written before coming to Taiwan titled On Poetry (論詩絕句) demonstrate the notion of emotion as the core of poetry, permeating throughout the piece. On Poetry best reflects his literary principle. After coming to Taiwan, he further promoted the idea of “Unity of the poet and his poetry” (詩人合一論). He opposed the views of some at the time who advocated “imitating the ancients”, or emphasized “creation”, separating the poet from his poetry. His view coincides with the famous saying of the Frenchman Buffon (1707-1788) that “The style is the man himself”. Additionally, Ch’en Han-kuang inherited the concept from the Great Preface to the Book of Songs (詩大序) that sounds are indicative of the rise and fall of a nation. He advised poets to compose with gentleness and honesty and avoid following the mournful and dejected styles of the “transformed style” (變風) and “transformed elegance” (變雅). If such styles of a chaotic era are followed, not only would they lead to personal decline but also would be harmful to the country. In this, he unreservedly expressed his patriotic sentiment.

Inside page of Han-kuang’s P’ien-wen Manuscript

Ch’en Han-kuang was especially skilled in p’ien-wen or parallel prose (駢文). His works were admired by cultural figures of late Ch’ing such as Wang K’ai-yün (王闓運 1833-1916), Liu Shih-p’ei (劉師培 1884-1919), Huang Chi-kang (黃季剛 1886-1935) as well as P’u Yu (溥儒). He published a facsimile volume titled Han-kuang’s P’ien-wen Manuscript (含光儷體文稿). Chiang Chao-shen (江兆申 1925-1996) recalled that when he studied under Mr. P’u Yu, he heard Mr. P’u talked about various contemporary literati, and singled out Mr. Ch’en as the most outstanding. Later, Ch’en met Chou Ch’i-tzu (周棄子 1912-1984) of Ta-yeh (大冶). Ch’i-tzu was most proud of his own poetry and rarely approved of others, but he showed great respect to Ch’en Han-kuang.

The calligraphy of Ch’en Han-kuang is lauded by many. Wang Chung (汪中 1925-2010) once ranked him alongside Yu Yu-jen (于右任), P’u Yu (溥儒), T’ai Ching-nung (臺靜農 1902-1990) and Liu T’ai-hsi (劉太希 1898-1989) as one of the “Five Calligraphy Masters Who Crossed the Sea”.

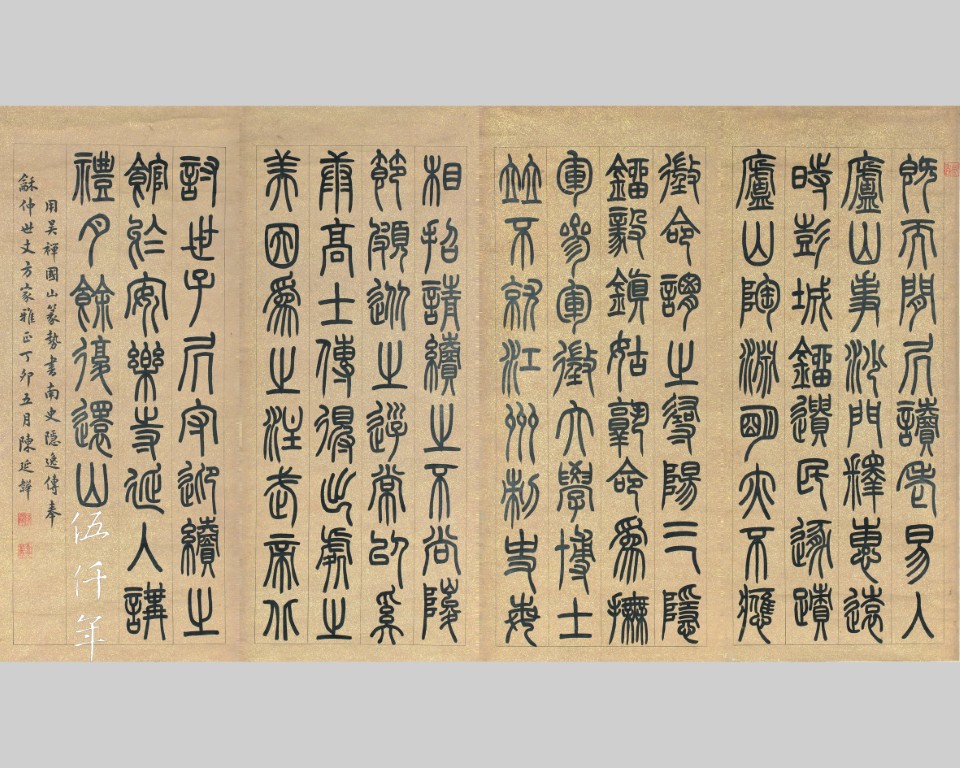

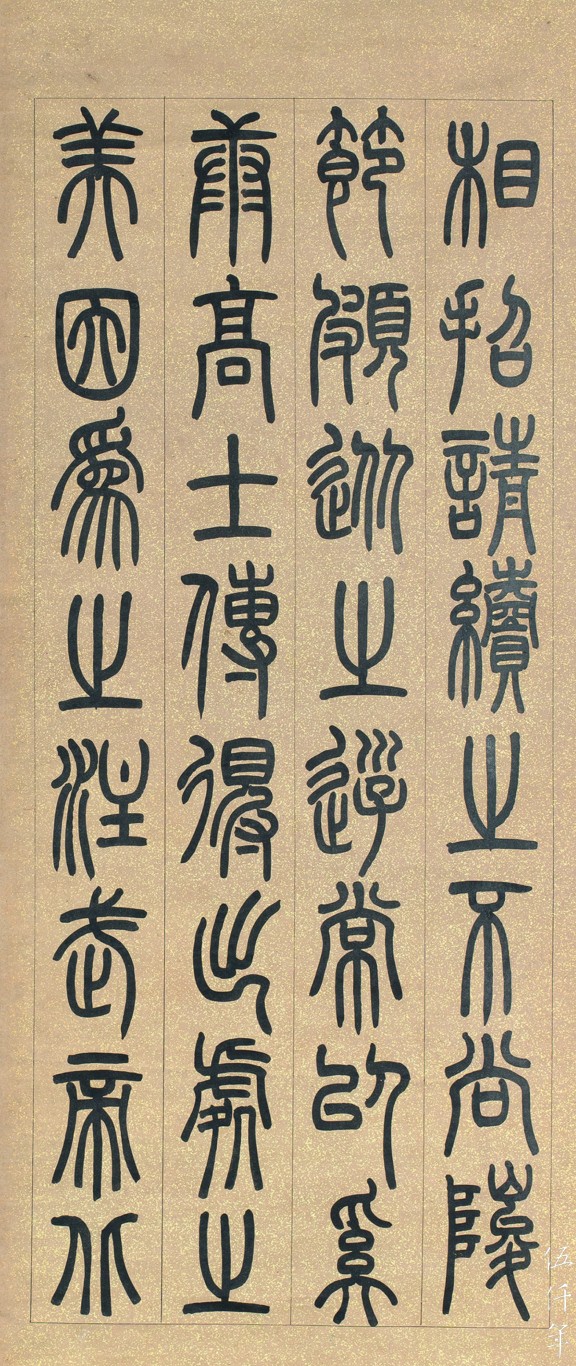

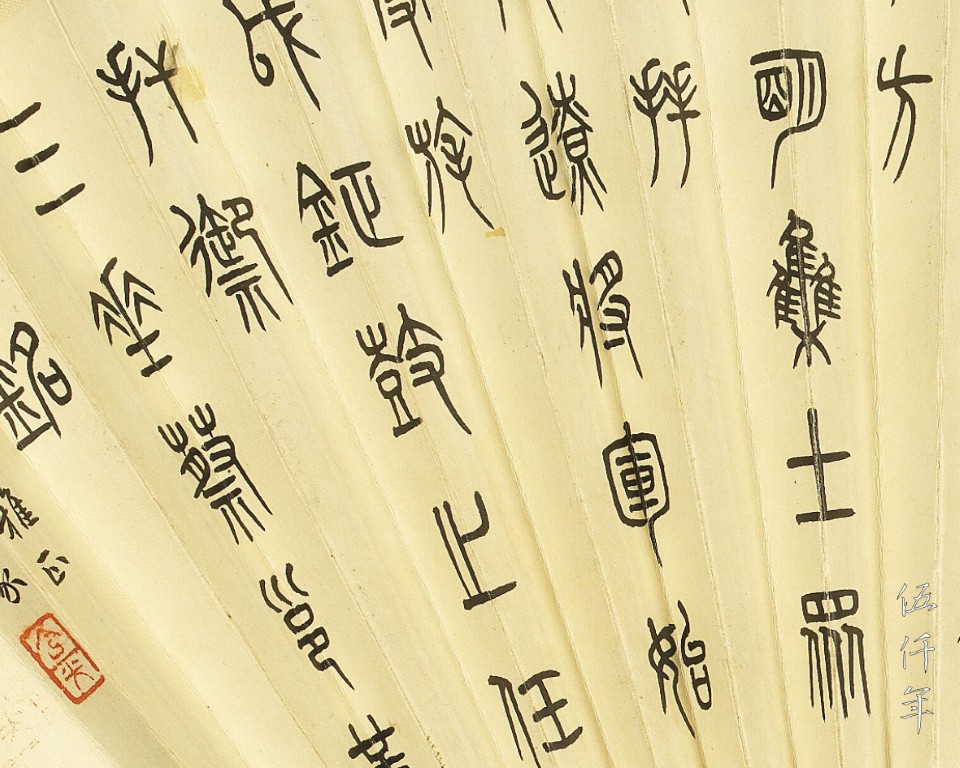

A set of four calligraphy pieces in seal script by Ch’en Han-kuang

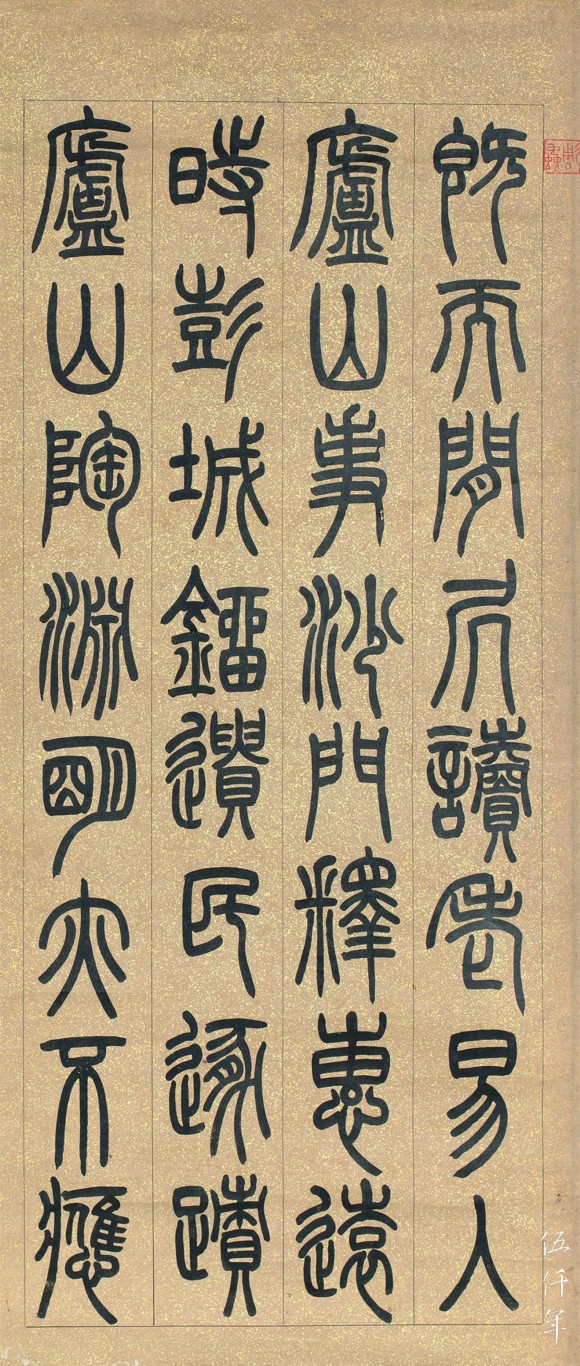

The first calligraphy scroll of the set of four in seal script by Ch’en Han-kuang

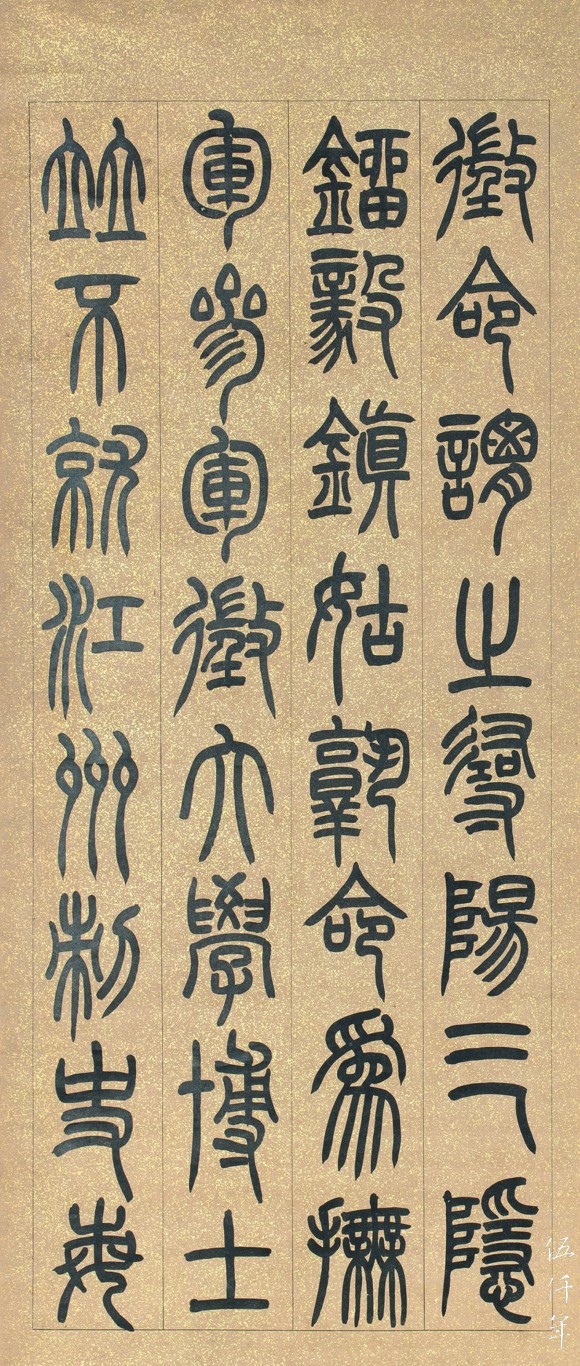

The second calligraphy scroll of the set of four in seal script by Ch’en Han-kuang

The third calligraphy scroll of the set of four in seal script by Ch’en Han-kuang

The fourth calligraphy scroll of the set of four in seal script by Ch’en Han-kuang

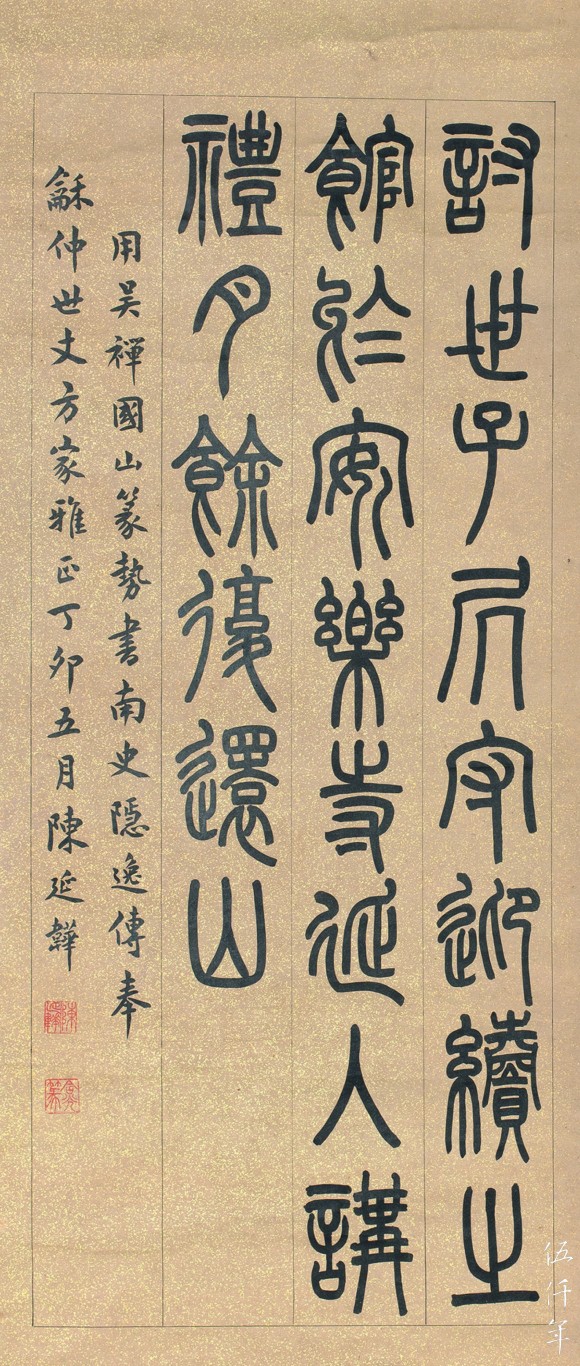

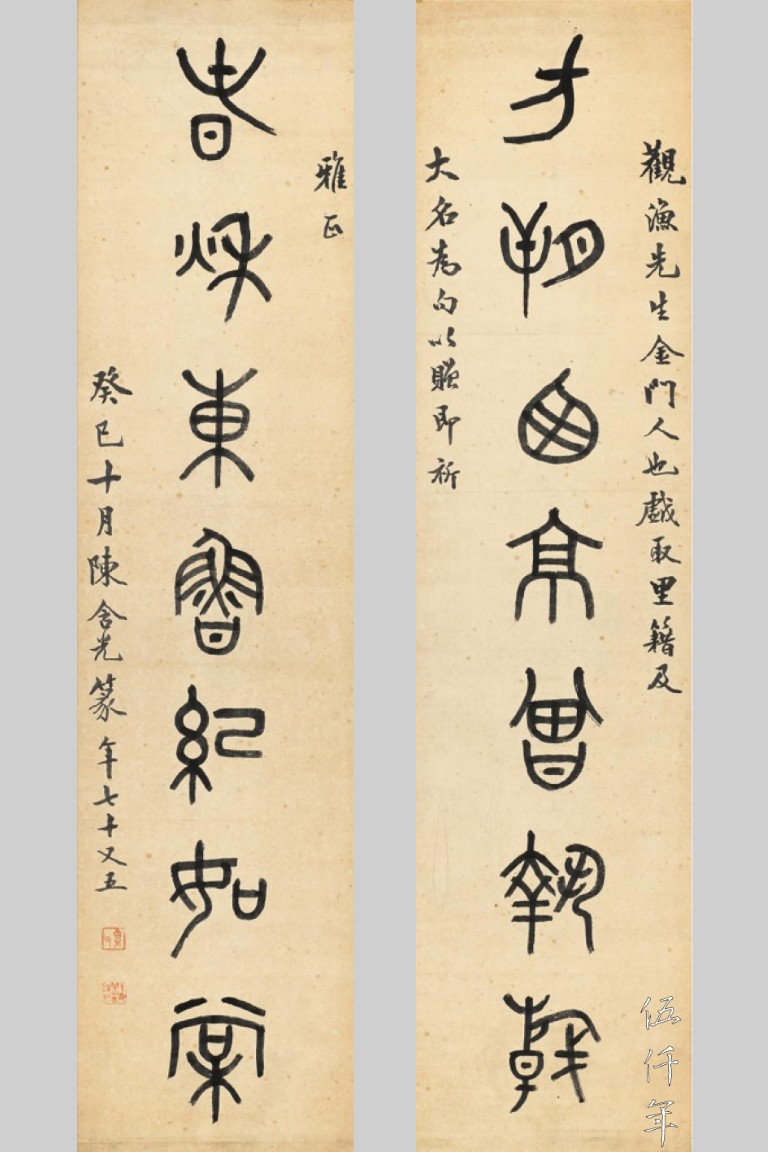

Ch’en excelled in both seal script and regular script calligraphy, his seal script being the most admired. He thoroughly studied the lexicography dictionary Shuo-wen Chieh-tzu (說文解字) and mastered a wide range of calligraphy styles beginning from the bronze inscriptions of Western Chou dynasty. His seal script calligraphy is elegant and refined. He did not limit himself to learning just from Li Yang-ping (李陽冰) of the T’ang dynasty. He also incorporated the styles of other T’ang dynasty calligraphers. Among Ch’ing dynasty calligraphers, he held Wu Ta-ch’eng (吳大澂 1835-1902) in the highest regard, praising Wu for incorporating the techniques of ancient bronze and stone inscriptions into small seal script, thereby achieving a robust and unparalleled style amongst his contemporaries. When teaching seal script calligraphy, Ch’en would start with Radicals of Shuo-wen Chieh-tzu by Yang Yi-sun (楊沂孫 1813-1881) and advanced with Preface to Shuo-wen Chieh-tzu by Yang. Li You (李猷 1915-1997) deemed that Ch’en Han-kuang “opened a new dimension for seal script calligraphy”. Mr. Chiang Chao-shen (江兆申) also held his seal script calligraphy in high esteem, believing that Chen’s fame as a poet overshadowed his name as a calligrapher.

A pair of calligraphy couplets in seal script by Ch’en Han-kuang

Regarding regular script calligraphy, Ch’en Han-kuang championed the theory of the “Two K'ai”. He said: “The period from K’ai-huang (開皇 581-600) to K’ai-yüan (開元 713-741) can be called the ‘Two K’ai’. This period is indeed the pinnacle of regular script calligraphy. Students can select a calligraphy stele from the period of the Two Kai according to their preferences and inclinations. Through diligent practice, calligraphy can certainly reach its peak”. Ch’en Han-kuang practiced regular script calligraphy in his early years for the sake of public examination. He studied Yü Shih-nan (虞世南 558 AD-638 AD) and Ou-yang Hsün (歐陽詢 557 AD-641 AD). Later he gave up his aspiration of an official career. In middle age, he applied himself to the small regular script of Chin dynasty (晉 266-420). After years of practice and refinement, he finally attained the calligraphy style of Chin. Five Poems by Huai-t’ang Dedicated to Ch’en Shih-ts’eng (書槐堂為陳師曾賦五首) written for his close friend Yin Shih-kung (尹石公 1888-1971) before he fled to Taiwan is a representative work. His regular script calligraphy had transitioned from the elongated form of the T’ang calligraphers to a broader and flatter style. Before the age of sixty, he switched again to learning the style of Ou-yang Tong (歐陽通 625 AD-691 AD). The regular script calligraphy of Ou-yang Tong also has a flat structure with a low center of gravity, similar in tone to the small regular script of the Chin dynasty, thus making it easy to adapt. I conjecture the reason he studied Ou-yang Tong was due to the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War, the occupation of Yang-chou by the Japanese army, the coercion he personally experienced, and the grief and anger from the martyrdom of his relative and friend. He adopted the vigorous calligraphy style of Ou-yang Tong to express the depth of his emotions. Ch’en Han-kuang’s regular script calligraphy underwent three phases. In the beginning he studied Yu Shih-nan (虞世南) and Ou-yang Hsün (歐陽詢). Afterwards he studied the small regular script of Wang Hsi-chih (王羲之 303 AD-361 AD) of the Chin dynasty. In his later years he studied the calligraphy of Ou-yang Tong. Each phase was closely related to his life experience and aspiration. His regular script reflects his life experience more than his seal script.

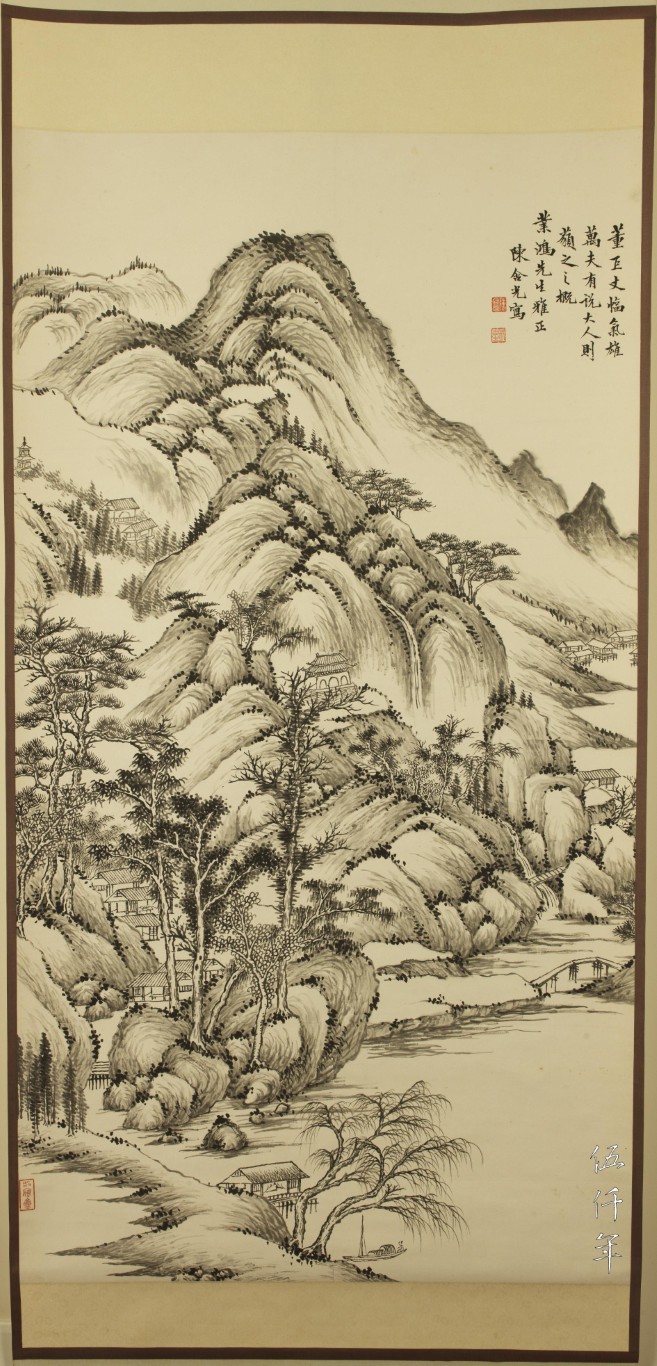

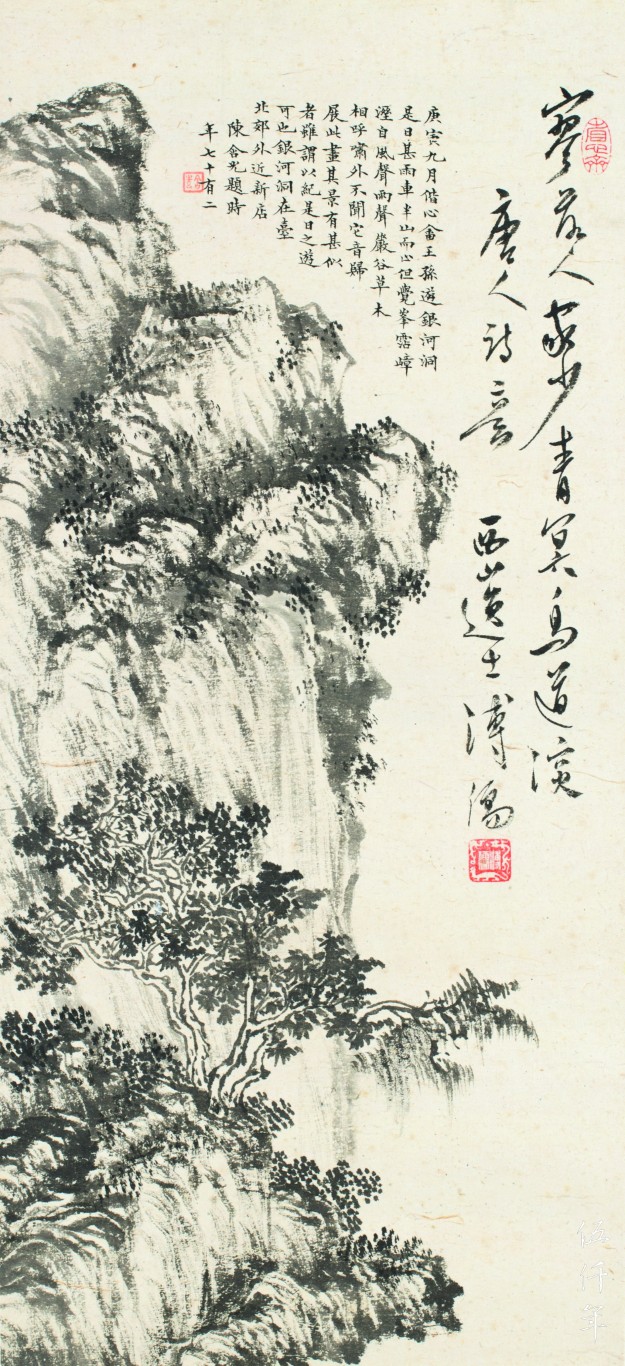

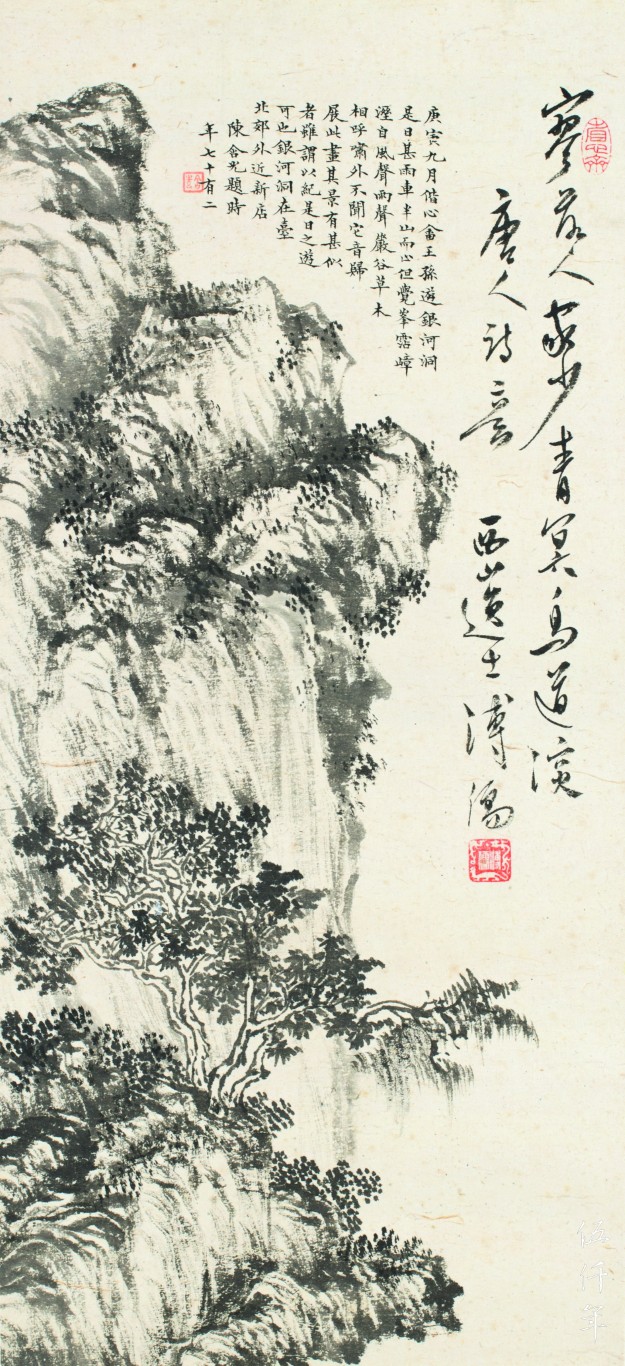

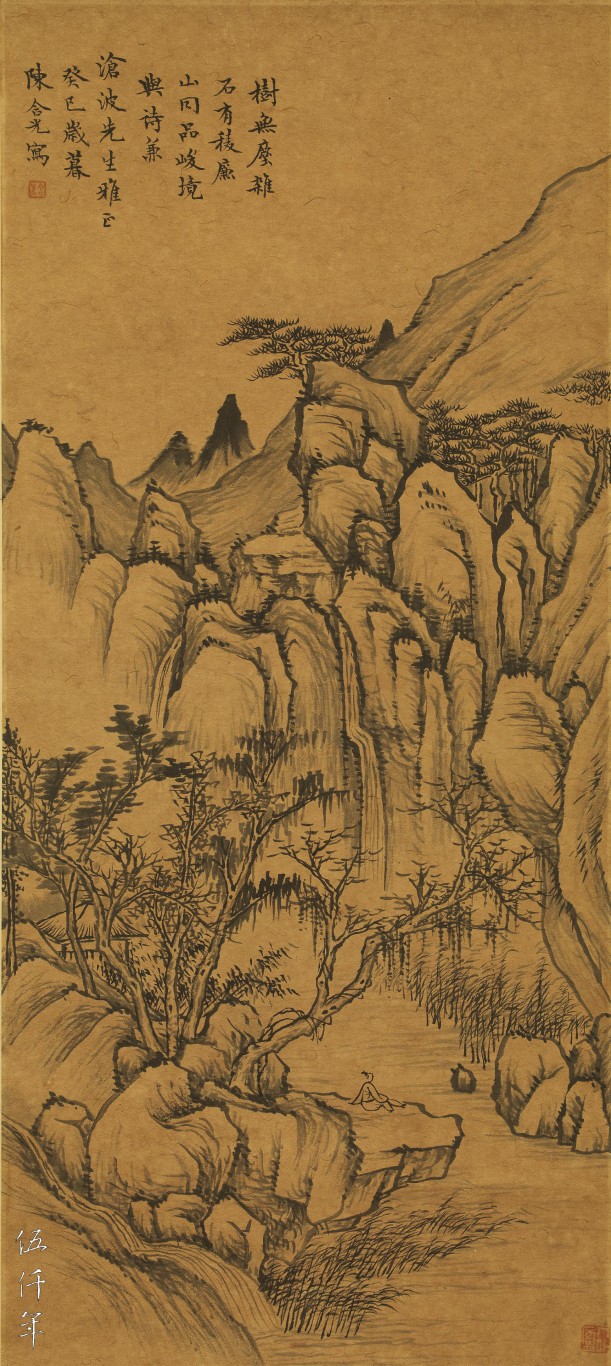

Hanging scroll of landscape painting by Ch’en Han-kuang

Detail of landscape painting by Ch’en Han-kuang

Ch’en Han-kuang was also skilled in painting, particularly landscapes. During his time in mainland China, he was already receiving commissions for his paintings in Shanghai. After coming to Taiwan, he held an art exhibition on one occasion. Looking at his extant paintings, he derived his style from a wide range of sources. His artistry can be traced to Tung Yüan (董源 934 AD-962 AD) and Chü Jan (巨然) of the Five Dynasties, the Four Masters of the Yüan dynasty and the Four Wangs of early Ch’ing dynasty. Among these, Wang Meng (王蒙 1308-1385) and Huang Kung-wang (黃公望 1269-1354) of the Yüan dynasty, and Wang Hui (王翬 1632-1717) of the early Ch’ing dynasty greatly influenced him. His brushwork was influenced by Wang Meng (王蒙), also borrowing those used in cursive and seal scripts. His strokes were executed by applying a half of the brush (中鋒), resulting in clean, vigorous and graceful brushwork. They were undertaken with meticulous care. The poetics of his painting is serene and detached, imbued with a strong literati atmosphere. However, Ch’en Han-kuang modestly commented that his landscape paintings only displayed brushwork without ink depth. He praised the work of P’u Yu instead.

Front of fan painting by Ch’en Han-kuang

Detail of front of fan painting by Ch’en Han-kuang

Back of fan painting by Ch’en Han-kuang

Back of fan painting by Ch’en Han-kuang

Ch’en Han-kuang and P’u Yu shared a deep friendship. Ch’en Han-kuang considered P’u Yu to be someone whose character and art were unrivaled in the last three hundred years. P’u Yu also greatly admired Ch’en Han-kuang’s character and art. Not only did he praise Ch’en Han-kuang’s p’ien-wen as unmatched at the time, he also told his son Hsiao-hua (孝華) to study under Ch’en Han-kuang. The two often traveled together, wrote and exchanged poems, and collaborated on painting. According to the recollection of Chang Pai-ch’eng (張百成), a disciple of Ch’en Han-kuang, when people received a painting by P’u Yu, they would hope for an inscription by Ch’en Han-kuang, naming it “Pu painting Ch’en inscription”. Both conducted their lives according to Confucian principles, they were also aloof and reclusive. In their later years both wandered far from home, finding refuge by the shore. They shared similar aspirations and scholarly pursuits, nurturing mutual respect and appreciation. They left behind a number of exchange poems and painting collaborations, enriching the artistic legend of the Republic of China.

Landscape painting by P’u Yu, calligraphy inscription by Ch’en Han-kuang

Detail of landscape painting by P’u Yu, calligraphy inscription by Ch’en Han-kuang

Surveying the life of Ch’en Han-kuang, he had indeed adhered to the principles of a Confucian scholar. He was conscientious of his conduct, and acted according to strict boundaries. He was detached from fame and fortune, and avoided contention with others. He regularly found solace in poetry and art, much like T’ao Yüan-ming (陶淵明 365 AD-427 AD) of the Eastern Chin dynasty. During the Japanese occupation of Yang-chou, he resolutely stood up for the national cause without the least concession. Later with the fall of mainland China to the communists, and the relocation of the Central Government of the Republic of China to Taiwan, he strongly advocated for cultural revival through poetry and education, with unwavering patriotic spirit and commendable integrity. Apart from his moral character, his artistic achievements were also exceptional, excelling in all the domains of poetry, prose, calligraphy and painting. Not only was he celebrated at his time, but his work is worthy to be recorded in history. In the tradition of Chinese scholars who aspire to attain the “Three Deeds to Immortality: Virtue, Achievement or Words”, does not Ch’en Han-kuang stand as embodiment of both Virtue and Words?

Hanging scroll of landscape painting by Ch’en Han-kuang

Detail of landscape painting by Ch’en Han-kuang