Tai Hsi (1801-1860), the junior vice-president of the Board of War, was skilled in poetry and excelled in painting. In the 10th year of the Hsien-feng reign (1860), the Taiping army conquered Hangchou. Tai Hsi, together with his brother, daughter-in-law and nephew, committed suicide by jumping into a well. He wrote a poem beforehand to articulate his deed. The scholar-official of the past advocated righteousness and integrity, and in time of chaos, these convictions loomed ever more pronounced. By retracing the final poem, the final letter, and a work on paper by Tai Hsi, the inner sanctum of the moral universe of an ancient martyr can perhaps be illuminated.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

Detail of A Homecoming Boat Along Autumn Hills

In the 3rd year of the Hsien-feng reign (1853), the army of Taiping Heavenly Kingdom conquered Chiang-ning (江寧) prefecture, also known as Nanking, of Chiangsu province. The Taiping rebels renamed the prefecture T’ien-ching, (天京) Heaven’s Capital. In January the 10th year of the Hsien-feng reign (1860), the army of the Manchu Ch’ing dynasty surrounded T’ien-ching. In February, Prince Loyal Li Hsiu-ch’eng (李秀成) led an elite Taiping army to attack Hangchou, to alleviate the siege. The officials and citizens of Hangchou were in fright and panic, the civil and military officials gathered together to discuss the entrenched defense of the city walls and the secured closure of the city gates. Li Hsiu-ch’eng captured a group of miners in Chiang-shan (江山) of Chekiang province, he ordered them to dig trenches and tunnels to reach the section of the city wall between Fêng-shan (鳳山) Gate and Ch’ing-po (清波) Gate. A number of coffins were filled with dynamite, and were shoved into the wall below the gun deck of the large cannons. At daybreak on 27th February of the Chinese Agricultural Calendar, a huge explosion occurred, the gun deck was completely destroyed, the city wall was breached, and the Taiping army rushed in.

Fêng-shan Gate of Hangchou City. Photograph courtesy William Edgar Geil

Ch'ing-po Gate of Hangchou City. Photograph courtesy Sidney D. Gamble

In An Eyewitness Account of the Double Occupation of Hangchou, by an anonymous author, there was a detailed description of the plunder by the armies of both sides after the fall of Hangchou in the 10th year of the Hsien-feng reign (1860):

“(The Taiping Army) was pillaging daily for gold, silver, treasures and raping women, they did not attack the barracks of the Manchu banners, nor did they cross the boundary of Chung-an (眾安) Bridge. As workers from the tin foil shops and textile mills were united, together they built mud walls for defense, hence there were less victims at Ch’ien-t’ang (錢塘) Gate, Wu-lin (武林) Gate, Liang-shan (良山) Gate and T’ai-p’ing (太平) Gate. This went on for a few days. Suddenly on the 3rd of March (Chinese Agricultural Calendar), there was news that the Taiping Army had completely withdrawn, the bold and curious in the city noticed the vacant houses of the wealthy, and made off with their valuables. When those in the barracks of the Manchu banners heard this, all the soldiers came out to loot the population, irrespective of large or small shops, houses of the rich or the poor, no matter what items, and proclaimed: If the Taiping bandits were not defeated by us, how could your life or lives of your family be preserved? Looting by soldiers and natives continued for approximately ten days.”

The Taiping Army attacked Hangchou to alleviate the seige of T’ien-ching, they did not wish for a protracted fight nor the occupation of Hangchou in the first place. Many civil and military officials died in battle and committed suicide. After the withdrawal of the Taiping Army, government buildings were deserted, and civil administration was paralyzed.

With the fall of Hangchou, some of those who died in battle were Wang Yu-tuan (王友端), provincial administration commissioner of Chekiang province; Mou Tzu (繆梓), salt distribution commissioner of Chin-hua (金華), Ch’ü-chou (衢州) and Yen-chou (嚴州) Circuits of Chekiang province; Chung Sun-mao (仲孫懋), intendant of Ning-po (寧波), Shao-hsing (紹興) and T’ai-chou (台州) Circuits of Chekiang province; expectant circuit appointee Ch’en Ping-yüan (陳炳元) ; Ch’eng Pao-an (程葆安), prefect of Chao-ch’ing (肇慶) of Kwangtung province, and others.

Some of those who committed suicide were Lo Tsun-tien (羅遵殿), governor of Chekiang province, together with his wife and daughter committed suicide by poisoning; Yeh K’un (葉堃), intendant of Hang-chou (杭州), Chia-hsing (嘉興) and Hu-chou (湖州) Circuits of Chekiang province, with his son committed suicide by jumping into well; Ma Ang-hsiao (馬昂霄), prefect of Hangchou; Li Fu-ch’ien (李福謙), district magistrate of Jen-ho (仁和), and his nephew Li Yüan-hsi (李元熙) who was captured and killed while berating the enemy. Tai Hsi, junior vice-president of the Board of War, with his brother Hsü (煦), who attained the hsiu-ts’ai (秀才) degree, his daughter-in-law Chin (金), his nephew Wang Chao-jung (王朝榮), all committed suicide by jumping into a well. When the year becomes cold, then we know how the pine and cypress are the last to lose their leaves. In troubled times we may encounter the loyal and righteous. To sacrifice life to preserve virtue in a state of composure is already not easy, for father and son, husband and wife, brothers, or members from different generations to commit suicide together is particularly challenging.. The Confucians of the past cultivated and nourished their righteousness and reason, reaching a profound state of the mind.

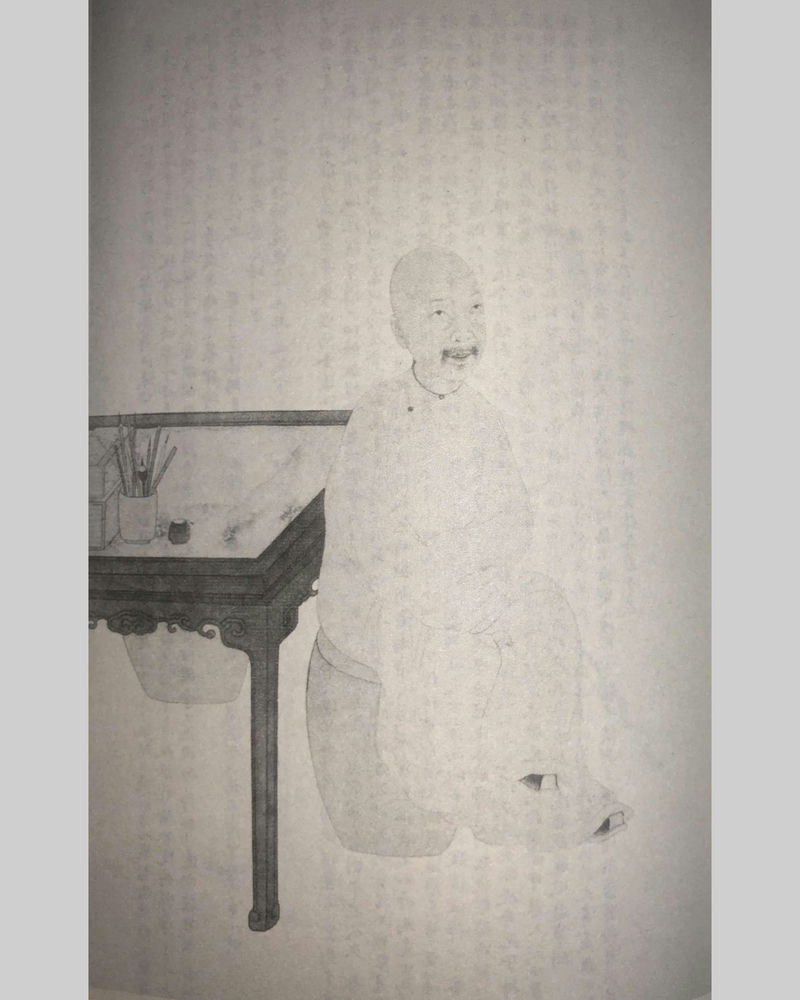

Portrait of Tai Hsi

The junior vice-president of the Board of War was Tai Hsi (戴熙 1801-1860), tzu Ch’un-shih (醇士), Ch’un-shih (蒓涘), hao Lu-ch’uang (鹿床), Lun-an (棆庵), Yü-an (榆庵), Meng-hsin (孟辛), Sung-p’ing (松屏), Ching-tung Chü-shih (井東居士). His studio names were Tz’u-yen Chai (賜硯齋), Hsi-k’u Chai (習苦齋), Ch’u-shu T’ang (竹書堂), Ch’un-meng An (春夢盦), Chiu-hua Shu-wu (韮花書屋). He was a native of Ch’ien-t’ang, Chekiang province. He attained the chü-jen degree in the 24th year of the Chia-ch’ing reign (1819), and the chin-shih degree in the 12th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1832). He was first appointed as observer to the Hanlin Academy, then compiler, and served in the Imperial Study. He was appointed educational commissioner of Kwangtung province, he occupied the position of grand secretary of the Grand Secretariat a number of times, and was also appointed junior vice-president of the Board of War. When he chose martyrdom in Hangchou, he was aged fifty nine. He was posthumously awarded the rank of minister, Commandant of Cavalry, Commandant of Fleet-as-cloud Cavalry, a posthumous name Wen-chieh (文節) was bestowed, and a special temple was ordered to be built for him in his native town. Tai Hsi was skillful in composing essays and poetry. He also excelled in painting, they were refined and enduring, celebrated throughout the whole country. His works include A Study of the History of the Book of Documents (尚書沿革考), Examinations for Official Promotions (書三考), Anthology of Poetry from Hsi-k’u Chai (習苦齋詩集), Writings from Hsi-k’u Chai (習苦齋文集), Musing on Painting from Hsi-k’u Chai (習苦齋畫絮), Random Record of Painting Colophons (題畫偶錄), A Compilation of Notes on Ancient Coins (古泉叢話).

In A Record of the Poetry Companions of Wei Yüan compiled by Li Pai-jung (李柏榮), there is a detailed account of the death of Tai Hsi:

“Li Hsiu-ch’eng (李秀成) struck at the territory of Chekiang again, unsettling a number of cities. At the time, the governor of Chekiang was Lo Tsun-tien (羅遵殿), he was dispirited and looked despondent, unclear what action to take. Tai Hsi devised and proposed a few schemes for war and defense, none was heeded. Lo erroneously trusted the plan by Mou Tzu (繆梓), the city fell, Lo died, and Tai Hsi also died. In the final desperate moment, Tai Hsi realized the situation could no longer be salvaged, he arranged his attire properly, and leisurely wrote a poem:

My ailing body of old meets the borderline of time,

Eight years of defense patrol only amount to shame;

I let go of myself into a heap of white clouds,

From now I no longer wish to return to human fold.

He then jumped into the water.”

Reading his final death poem, there was no hesitation to enact his moralistic stance, in his mind life and death were equally ephemeral as a passing cloud. Later generations are impelled in awe and reverence.

At daybreak on 27th February (Chinese Agricultural Calendar), the city of Hangchou fell, in the evening of 28th, in the midst of disintegration and decimation, Tai Hsi wrote a letter to Chang Pi-t’ien (張璧田), the chief commander-general, seeking reinforcements. It reads:

“In emergency. Dear sir: Since the morning of 27th, the city is in chaos, the soldiers faced the catastrophe bravely. The bandits set fire on all sides, and officials died in succession. The reinforcements that arrived, are nowhere to be found, those that are to arrive, there is no news. Yet the bandits are in fact slight in numbers, sometimes a few, sometimes only scores. Your excellency has a venerable reputation, lives of the whole city is solely dependent on your excellency. If you can set forth at the speed of fire, you can open up the road to life, and the state of the southeast, is still redeemable. I am imploring not just for the lives of the whole of Chekiang province. I especially deliver this urgent report. Tai Hsi kowtowed nine times. 28th February, in the hours of hsü (戌, between 7pm to 9 pm).”

It was indeed a soul stirring moment when life was hung by a thin thread. The house had now fallen, the only thing left was to offer full loyalty. It should be sometime during any of these three days: 29th February, 1st March, 2nd March, when Tai Hsi committed martyrdom. The Taiping Army withdrew to return to T’ien-ching on 3rd March.

In his lifetime, Tai Hsi enjoyed an exalted reputation for his painting. After his appointment to become educational commissioner of Kwangtung province, he took leave of Tao-kuang emperor, and the emperor said: “In order to paint well, the ancients travelled thousands of thousands of miles for inspirations, your trip will entail traveling through mountains and rivers, your painting will further advance.” We can observe the emperor’s high regard for Tai Hsi.

Preface by Yü Yüeh in Musing on Painting from Chih-k'u chai. Photograph courtesy Tu-hsing Antiquarian Bookshop

In the 19th year of the Kuang-hsü reign (1893), Hui Nien (惠年) compiled and published Musing on Painting from Chih-k’u Chai (習苦齋畫絮), he asked the distinguished scholar Yü Yüeh (俞樾) to write a prologue. It reads:

“Mr. Tai Hsi of the posthumous name Wen-chieh, was an eminent official in the Tao-kuang reign. His personal grace and literary talents are admired across the land. To investigate the reason, he was assigned to his posting at a time of danger, his rectitude was venerable, indeed a perfect man of his generation. Mr. Tai is not just remembered for his painting, those who cherish his moral character in our time, cherish his paintings more than ever. Since his death, no matter an inch or a foot of his work, is treasured over an ancient jade disc. His work on a folding fan, exceeds the cost of common gold, his work on a small scroll, is valued at thousands of taels. In modern times, those who achieved fame in calligraphy and painting, none surpasses the worth of Mr. Tai. Is it not the saying that mastery of art can advance into the realm of the Confucian Way? I cannot paint, how can I understand the theory of painting? I have been shown the printed book, and I merely wrote a few lines, for the world to know that Mr. Tai and the tu-chuan (都轉) are not just remembered for their paintings.”

Tu-chuan (都轉) is another name for the position of salt distribution commissioner. Hui Nien (惠年) was appointed to this posting for many years. His tzu was Ling-fang (菱舫), he was skilled in painting, he greatly relished Musing on Painting in Chih-k’u Chai, becoming a true literary soulmate. Hui Nien was a close friend of Yü Yüeh, when he passed away Yü Yüeh wrote a pair of memorial couplets. Reading the prologue by Yü Yüeh, we were informed that thirty three years after the death of Tai Hsi, his paintings were venerably collected. A painting is treasured because of the artist, and the artist is acclaimed because of his moral conduct. Chinese art since ancient time, is not just about the visual pleasure of brush and ink.That the name of Tai Hsi is so immortalized, is evidence of this premise.

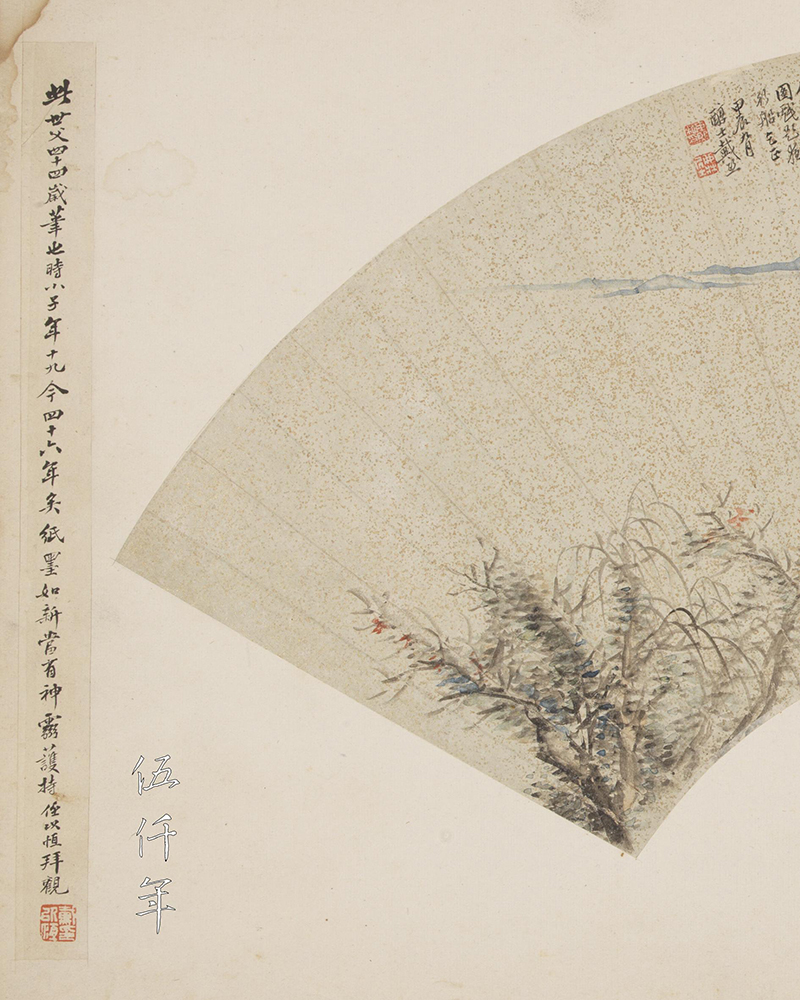

A Homecoming Boat Along Autumn Hills by Tai Hsi. Collection of Wen-miao hsiang Chai

In the collection of Wen-miao-hsiang Chai, there is a fan painting by Tai Hsi, the subject title is A Homecoming Boat Along Autumn Hills. In the painting, there are adjacent trees and distant hills, a leaf like boat, and miles of emptiness.

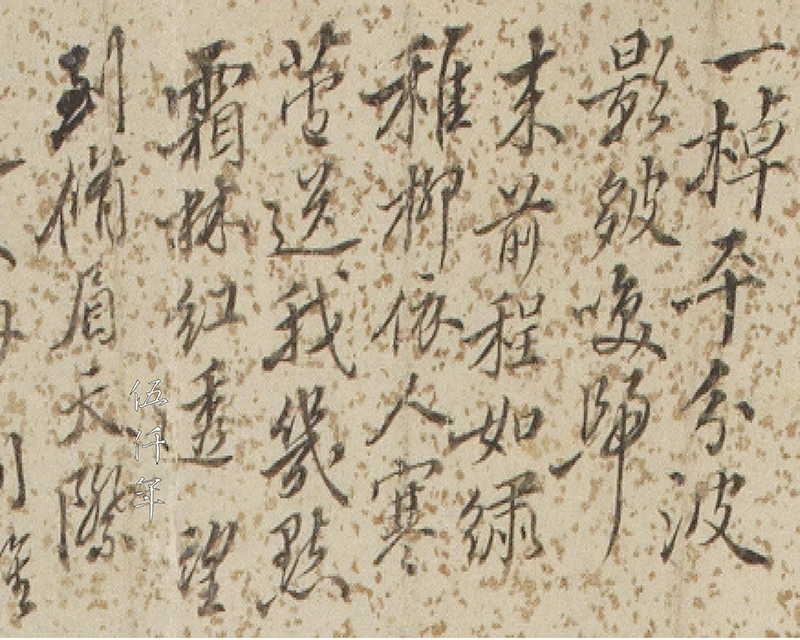

The tz’u poem on the painting reads:

A boat parting the waves

Of pleated shadow,

Calling

To go home

To voyage forward

In a silken scenery.

Young willows

Leaning,

Florets in the cold

Wave goodbye,

In the frosted woods,

Speckles of red

Seeping through.

Gazing the distant hills

Till the skyline freezes,

Once more in a hurry,

It is time to leave.

Veils of trivial melancholy,

A whiff of solitary grief,

Dreading the west wind

That scours one gaunt.

An-fu the fourth brother requested that I painted the picture A Homecoming Boat Along Autumn Hills. I playfully inscribed the tz’u poem To the tune Yeh hsing ch’uan and begged rectification. September of the year chia-ch’en (甲辰), Ch’un-shih Tai Hsi.

Seal impressions: “Private Seal of Tai Hsi (戴熙私印)” and “Lu-ch’uang Chü-shih (鹿牀居士)” .

The year chia-ch’en is the 24th year of the Tao-kuang reign (1844). At the time Tai Hsi was aged forty four. This painting was dedicated to An-fu the fourth brother, his biography unknown. The word brother here is only a courteous title used to address an elder friend. As Tai Hsi was a native of Hangchou, A Homecoming Boat Along Autumn Hills was perhaps inspired by the refined and delicate scenery of West Lake. Anthology of Poetry from Chih-k’u Chai by Tai Hsi is extant, but it is rare to come across his tz’u poem. This piece of tz’u poem To the tune Yeh hsing ch’uan should certainly be cherished.

To the tune Yeh hsing ch'uan inscribed on the painting

Beside the fan painting, there is a colophon by Tai I-heng (戴以恆). It reads:

“This is the brushwork of my uncle at the age of forty four. At that time, I was nineteen. Now I am already forty six. The paper and ink are fresh as new, it must have been blessed and protected by spirits. Nephew I-heng bowed respectfully to peruse.”

Seal impression:“Seal of Tai I-heng”

Detail of To the tune Yeh hsing ch’uan inscribed on painting

From this we learned that the painting was in the art collection of Tai I-heng (戴以恆 1826-1891). His tzu was Yung-pai (用柏), hao Ta-tsun (大樽), Tai-hsi T’ing-ch’ang (戴溪亭長), Ho-ch’u (鶴雛), his studio name was Ts’ui-su Chai (醉蘇齋), he was a native of Ch’ien-t’ang, Chekiang province. He was skilled in calligraphy and painting, and wrote Painting Methods of Ts’ui-su Chai. Some old books wrote that I-heng was the son of Tai Hsi. It is an error. I-heng was instead the nephew. In Musing on Painting from Chih-k’u Chai, it says: “Nephew Yung-pai loves painting so much as if it is submerged in his bones. In his spare time when away from his studies, he always enquires after the six principles of painting.” Now reading this colophon beside the painting, I-heng addressed Tai Hsi as his uncle, and inscribed the word nephew for himself. This is evidence to end past fallacy. Tai Hsi had two younger brothers, Tai Hsü (煦) and Tai Tao (燾), Tai Hsü committed martyrdom with him together in Hangchou. Tai Hsi had three sons, Yu-heng (有恆), K’ei-heng (可恆), Sui-sun (穗孫). One might speculate that when the earlier authors saw the names of the two sons, Yu-heng and K’ei-heng, both with the character heng, they mistakenly assumed that I-heng was also the son.

This year is the 161st death anniversary of Tai Hsi, I have attempted a crude account in his memory.

Colophon by Tai I-heng mounted next to the fan painting