The downfall of Peking Opera has been drastic indeed. In the early years of the Republic, it was prolific in the north and in the south. Even after the relocation of the Central Government to Taiwan, Peking Opera continued to shine for decades. However, its presence can now be only infrequently spotted. As a Virtual Museum dedicated to Chinese Classical Culture, despite the limited number of Opera aficionados, we should certainly dispense even greater efforts to its promotion. We hereby present the only live recording of the great opera soprano Ms. Chang O-yün performing in Wen-chi Returning to Han in Hong Kong in the 54th year of the Republic (1965). It is no less than the resurrection of the long lost Kuang-ling-san (廣陵散) zither lyric.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

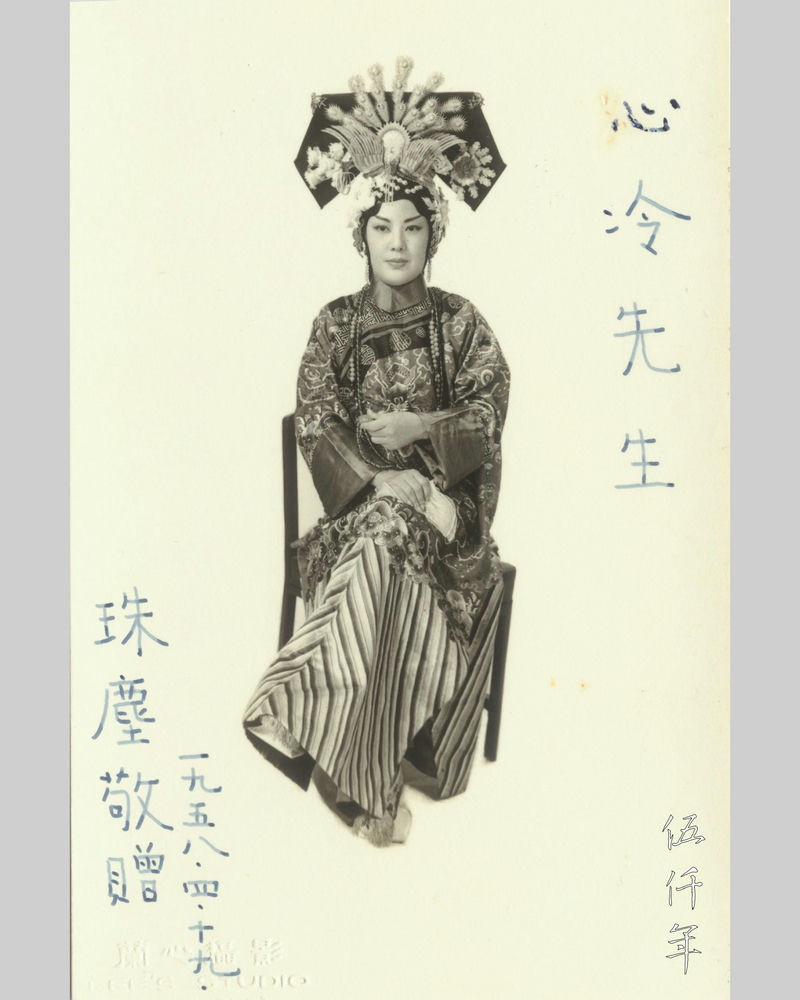

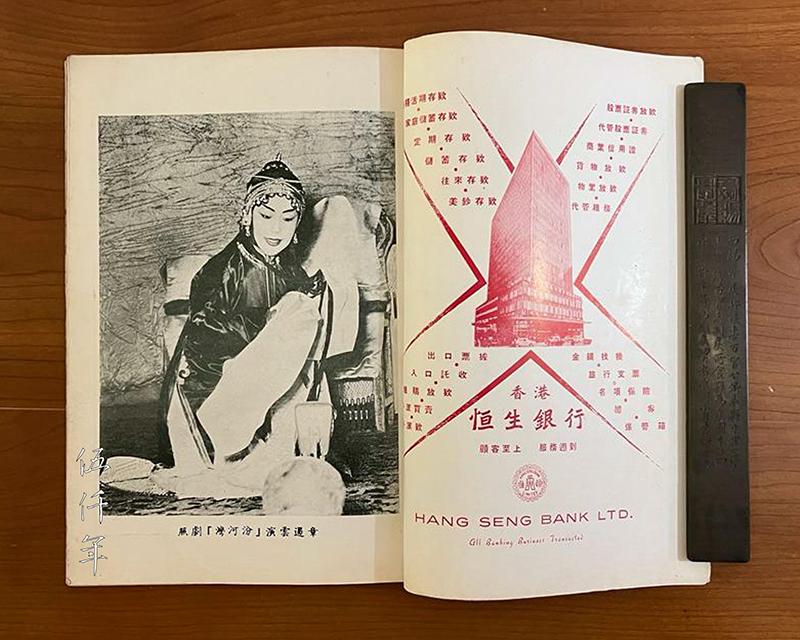

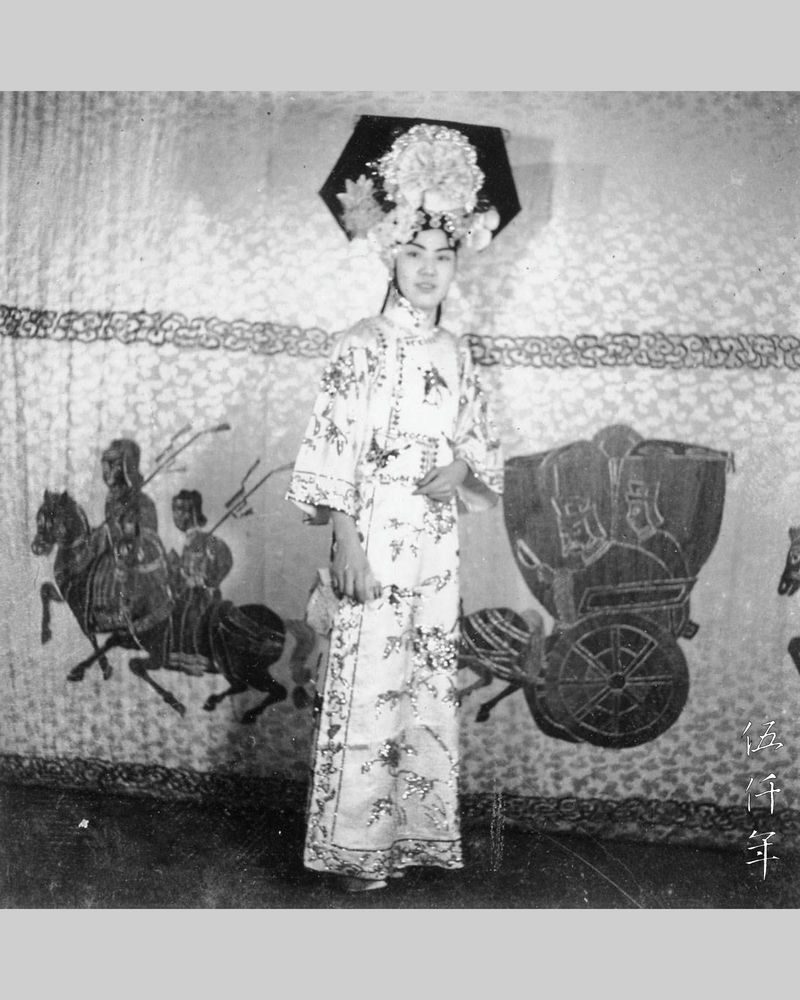

Picture of Aunt Chang O-yün performing in the opera Fen-ho Wan

T’ang dynasty is known for poetry (詩), Sung dynasty for tz’u lyric (詞), Yüan dynasty for ch’ü aria (曲), Ming and Ch’ing dynasties for novel (小說), and the early Republican era for P’ing-chü (or Peking Opera 平劇). Between the founding of the Republic of China in 1912, to the fall of mainland China to the communists in 1949, in this period of thirty eight years, even though the country suffered many calamities, P’ing-chü (or Peking Opera 平劇) was the rage from north to south. Swarms of celebrated performers and opera aficionados emerged. Such proliferation did not occur in the past.

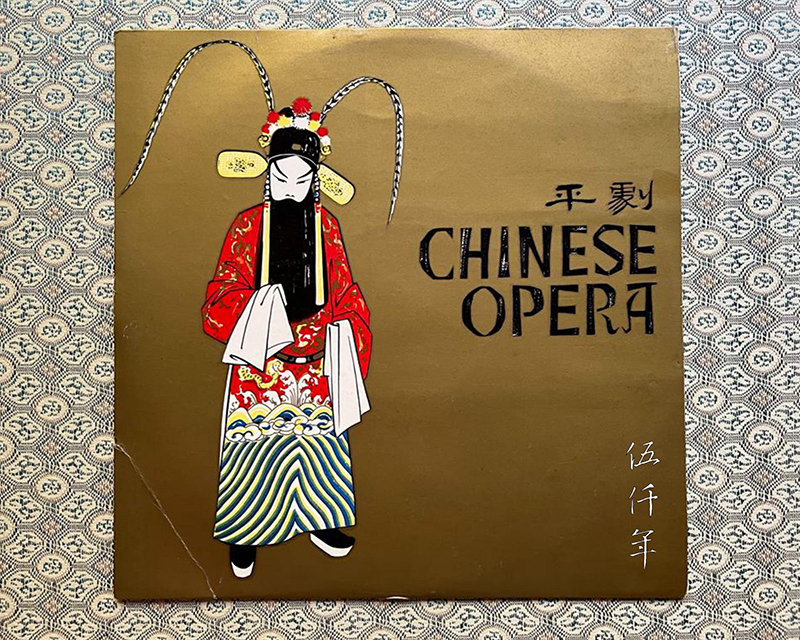

Front cover of gramophone record of P’ing-chü performed by Foo Hsing School of Dramatic Arts. The record was presented as visitor gift in the China Pavilion representing the Republic of China at New York World’s Fair in 1964

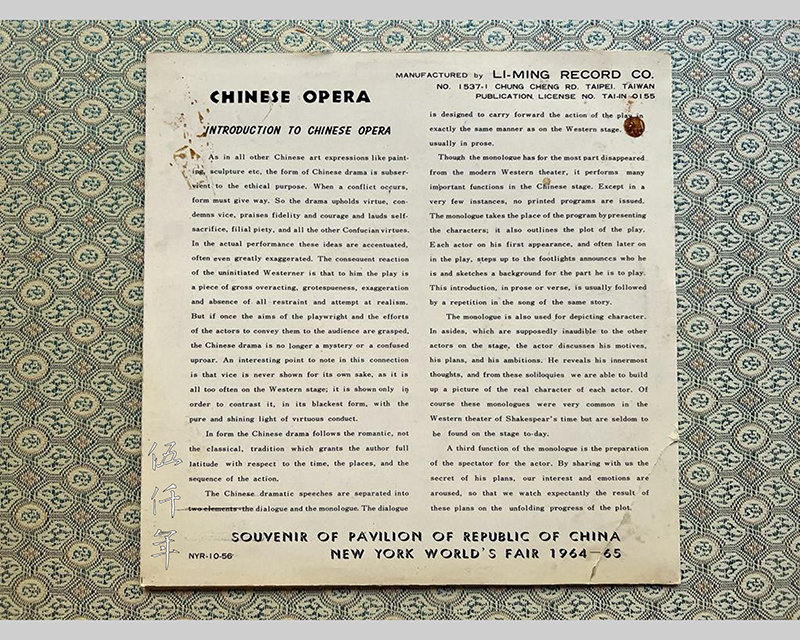

Back cover of gramophone record of P’ing-chü performed by Foo Hsing School of Dramatic Arts. The record was presented as visitor gift in the China Pavilion representing the Republic of China at New York World’s Fair in 1964

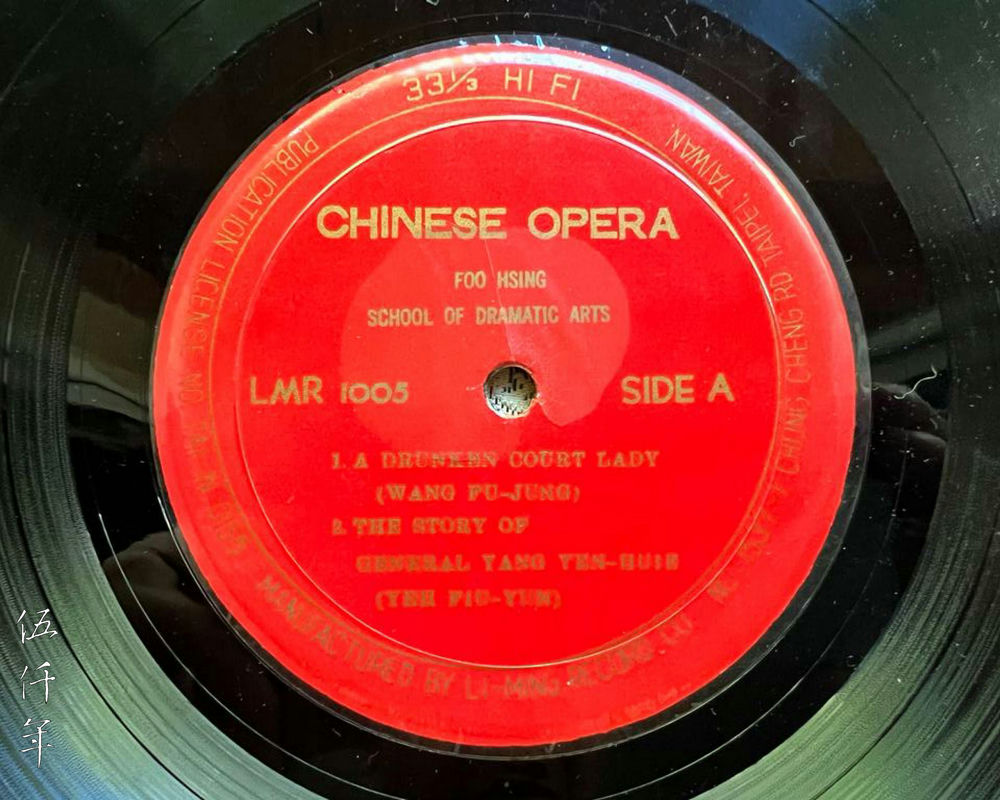

Gramophone record of Ping-chü performed by Foo Hsing School of Dramatic Arts. The record was presented as visitor gift in the China Pavilion representing the Republic of China at New York World’s Fair in 1964

Label of gramophone record of Ping-chü performed by Foo Hsing School of Dramatic Arts. The record was presented as visitor gift in the China Pavilion representing the Republic of China at New York World’s Fair in 1964

P’ing-chü (or Peking Opera) originated from Pei-p’ing (北平 Peking), hence it was named after the city. P’ing (平) means Peking and chü (劇) means opera. The name Pei-p’ing only came into being after the victory of the Northern Expedition and the unification of China in 1928. The Nationalist government renamed the city from Pei-ching (北京) to Pei-p’ing, thus P’ing-chü (平劇) can also be called by the former city name as Ching-chü (京劇). Additionally, it is also known as Kuo-chü (國劇), National Opera. P’ing-chü is ranked foremost among the many different endemic operas all over China, for none can match the allure of P’ing-chü.

As late as the 53rd year of the Republic (1964), when the government of the Republic of China took part in the New York World’s Fair, gramophone records of P’ing-chü performed by Foo Hsing School of Dramatic Arts (私立復興戲劇學校), were presented as gifts to visitors of the China Pavilion. The Republican hallmark of P’ing-chü is discernible. There is an album of this gramophone record in my house, a memento of former times.

A celebrated soprano of the P’ing-chü School of Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu (程硯秋), who was adulated in both the Republican period in mainland China and the Republican period in Taiwan, who continually performed on stage during the latter period in Taiwan and Hong Kong, whose virtuosity emerged to be ever more sublime, was none other than Aunt Chang O-yün (章遏雲).

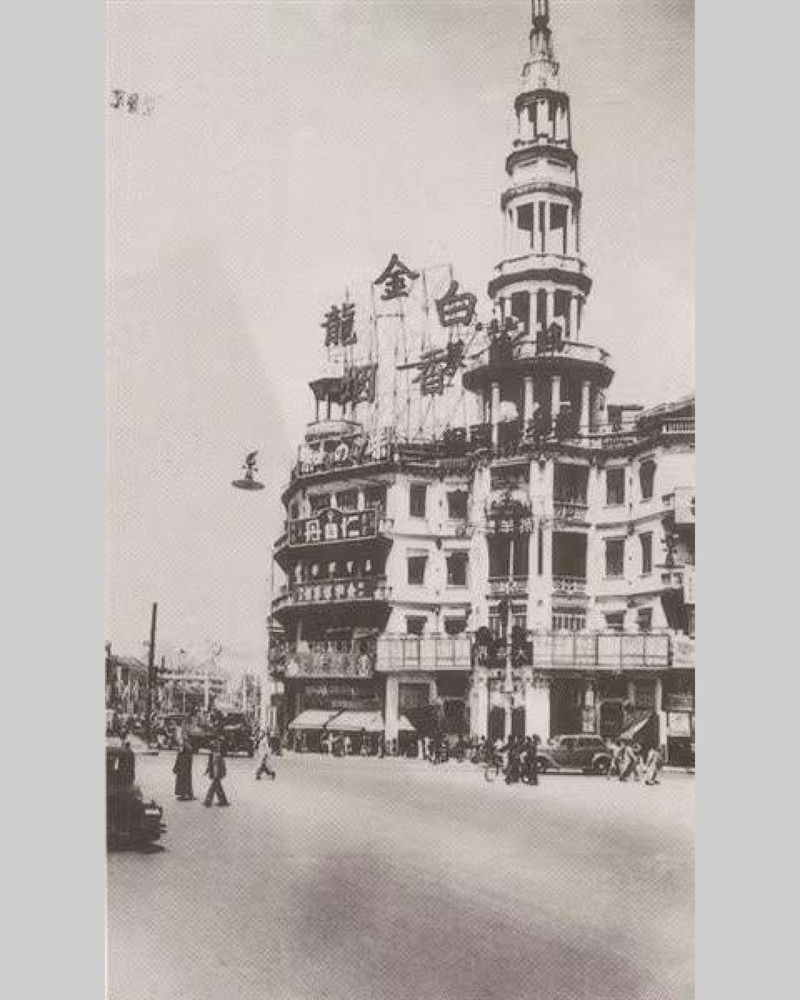

Aunt Chang O-yün first performed at the Great World Amusement Arcade in Shanghai

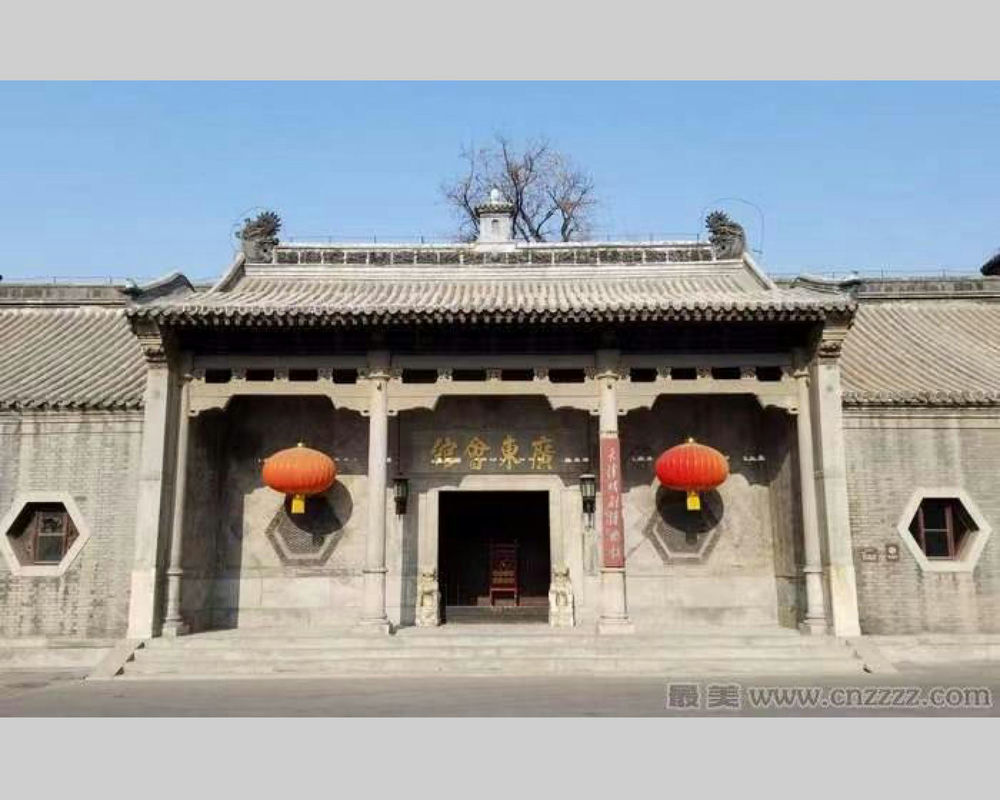

At the age of eleven or twelve, Aunt Chang O-yün performed at the Kwangtung Guild Hall in Tientsin

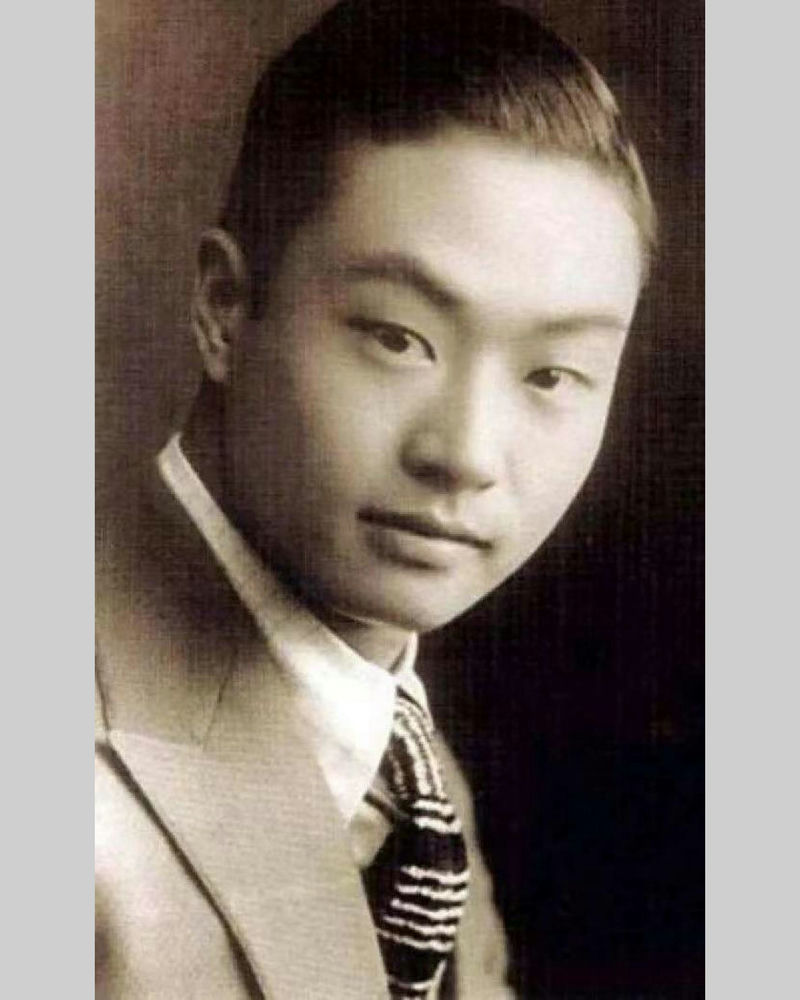

Aunt Chang O-yün (1912-2003), original name Feng-p’ing (鳳屏), hao O-yün (遏雲), Chu-ch’en (珠塵). The hao O-yün was christened by She Tzu-li (佘子立), the hao Chu-ch’en was christened by Yeh Kung-ch’o (葉恭綽). In time, the hao O-yün was mostly used. She was a native of Kwangtung Province, but spent her childhood in Shanghai. She learned to sing in the role of lao-sheng (older gentleman 老生) at a young age. Her first performance was in a cameo appearance in the opera Wu-chia P’o (武家坡) at the Ch’ien-k’un Theatre inside the Great World Amusement Arcade in Shanghai.

Soon after, Aunt Chang left Shanghai to study at a school in Tientsin. In her after class hours, her school teacher Wang Yü-sheng (王庾生) taught her to sing in the role of ch’ing-i (middle-aged woman 青衣). A few years later, at the age of eleven or twelve, she performed the role of ch’ing-i in the opera Fen-ho Wan (汾河灣) at the Kwangtung Guild Hall in Tientsin. The performance was well received by the audience, and ushered her decision to join the world of opera.

Many renowned opera teachers were then living in Peking. Aunt Chang’s mother Teng Hsiu-chih (鄧秀芝), who at one time used the name Chang Sou-chih (章瘦芝), accompanied her daughter to Peking. Enquiries were made all over the place to find suitable opera teachers, and in due course Aunt Chang studied under a number of prestigious singers: Li Pao-ch’in (李寶琴), Jung Tieh-hsien (榮蝶仙), Li Shou-shan (李壽山), Chang Ts’ai-lin (張彩林), Chiang Shun-hsien (江順仙), Lü Hsüeh-fang (律學芳) and T’ao Yü-chih (陶玉芝). Aunt Chang was able to make significant progress with her opera singing.

Portrait of Wang Yao-ch’ing (王瑤卿)

In the 19th year of the Republic (1930), she became a student of Wang Yao-ch’ing (王瑤卿 1881-1954). She received tuitions for the operas Ch’i-p’an Shan (棋盤山), Tiao-ch’an (貂蟬), K’ung-ch’üeh tung-nan fei (孔雀東南飛), Fu-shou ching (福壽鏡) and others, reaching ever higher level of virtuosity.

Portrait of Mei Lan-fang (梅蘭芳)

In the same year, The P’ei-yang Pictorial News in Tientsin launched a referendum for opera aficionados to vote on the four greatest contemporary k’un-tan (female performer 坤旦). Aunt Chang was elected as one of the four greatest k’un-tan. During this time, in order to thoroughly study the opera Pa-wang pieh-chi (霸王別姬), she became a student of Mei Lan-fang (梅蘭芳 1894-1961).

Portrait of Mu T’ieh-fen (穆鐵芬)

In the 21st year of the Republic (1932), Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu (程硯秋 1904-1958) went on a grand tour of Europe and disbanded his opera troupe. The hu-ch’in (胡琴) instrumentalist of the troupe, Mu T’ieh-fen (穆鐵芬), subsequently found employment with Aunt Chang. Mu T’ieh-fen was not only a hu-ch’in instrumentalist, he was also a librettist and a composer. With this collaboration, Aunt Chang switched her style of opera singing to follow the School of Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu.

Aunt Chang O-yün leased the Grand Theatre of Hankow in Hupeh Province for half a year

In the 23rd year of the Republic (1934), Aunt Chang leased the Grand Theatre of Hankow in Hupeh Province for half a year. Apart from arranging a session of her own performance, she also invited a session with Mei Lan-fang and his opera troupe, a session with Ma Lien-liang (馬連良 1901-1966), Huang Kuei-ch’iu (黃桂秋 1906-1978) and their opera troupe. Seating tickets and standing tickets were completely sold out. It was a sensation in Wuhan City and the earnings were substantial.

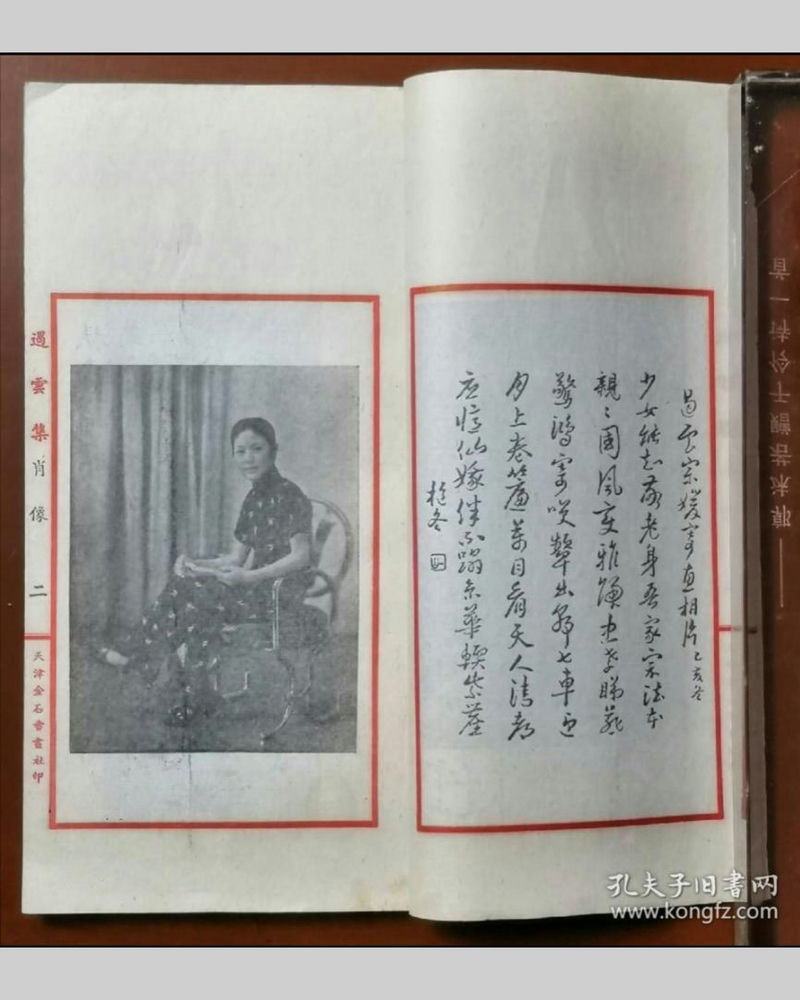

In Peking and Tientsin, there were many literati and Ch’ing loyalists who were enthralled by the opera performances of Aunt Chang. In the 24th year of the Republic (1935), Chang Ch’in (章梫 1861-1949), a member of the former Hanlin Academy of Ch’ing dynasty, presented a poem to Ms. Chang. Nearly a hundred other literati responded with poems, including Liu Ch’un-lin (劉春霖 1872-1942), Fan Tseng-hsiang (樊增祥 1846-1931), Fang Erh-ch’ien (方爾謙 1873-1936), Yüan K’ei-wen (袁克文 1889-1931) and others. These were compiled into O-yün chi (遏雲集), published by Tientsin Chin-shih Shu-Hua She (天津金石書畫社) in the 27th year of the Republic (1938).

Inside page of O-yün chi (遏雲集)

Aunt Chang was also accomplished in Yüeh-chü (or Cantonese Opera 粵劇), though little known. At one time she performed the Cantonese Opera Chi-t’a (祭塔) in Tientsin. Between the 19th year of the Republic (1930) to the 26th year of the Republic (1937), Aunt Chang was invited to produce a number of gramophone records, and her opera singings from these early years were thus preserved. In the 19th year of the Republic (1930), RCA Victor produced three gramophone records by Aunt Chang. The first record features the opera Hung-ni Kuan (虹霓關). The A-side and B-side of the second record feature the operas Hsing-hua ho-fan (杏花和番) and Te-i yüan (得意緣) respectively. The A-side and B-side of the third record feature the operas Huo-zhuo Wang-k’uei (活捉王魁) and Wu-hua Tung (五花洞) respectively. In the 20th year of the Republic (1931), The Great Wall Record Co. Ltd. produced two gramophone records by Aunt Chang. The first record features the opera Su-san ch’i-chieh (蘇三起解). The A-side and B-side of the second record feature the operas Fen-ho Wan (汾河灣) and Mei-lung Chen (梅龍鎮) respectively. In the 26th year of the Republic (1937), Pathe Records produced three gramophone records by Aunt Chang. The first record features the opera Lei-feng T’a (雷峰塔). The A-side and B-side of the second record feature the operas San-niang chiao-tzu (三娘教子) and Ch’i-p’an Shan (棋盤山) respectively. The A-side and B-side of the third record feature the operas Shih-yü-zhuo (拾玉鐲) and Hui-lung Ko (迴龍閣) respectively. I have kept a gramophone record of the operas Shih-yü-zhuo (拾玉鐲) and Hui-lung Ko (迴龍閣) by Pathe Records, as to dwell now and again on the residual sound of the past.

Front cover of gramophone record of the operas Shih-yü-zhou (拾玉鐲) and Hui-lung Ko (迴龍閣) by Pathe Records

Gramophone record of the operas Shih-yü-zhou (拾玉鐲) and Hui-lung Ko (迴龍閣) by Pathe Records

Label of gramophone record of the operas Shih-yü-zhou (拾玉鐲) and Hui-lung Ko (迴龍閣) by Pathe Records

The Marco Polo Bridge Incident broke out in the 26th year of the Republic (1937). Peking, Tientsin, Shanghai, Nanking fell to the invading Japanese army one after the other. Thereupon Aunt Chang declined all performances in the Japanese occupied territories. We can recognize the moral rectitude embraced by the celebrated soprano. In the 38th year of the Republic (1949), shortly before the fall of mainland China to the communists, she left for Hong Kong by herself, repudiating the rule of the communists. In the 42nd year of the Republic (1953), when Free China was still in a precarious position in Taiwan, she paid her first visit there as a member of the delegation from the film and opera sectors in Hong Kong, headed by the actor Wang Yüan-lung (王元龍). Aunt Chang made a special effort to visit the military base in Kinmen to sing for the troops.

In the same year, on 25th December Christmas Day, the infamous Shek Kip Mei Fire broke out in Kowloon, destroying streets of shanty houses. In spring the following year, Aunt Chang raised funds for the victims through the charity performance of the opera Liu-yüeh hsüeh (六月雪). It was also her first stage performance in Hong Kong. Although she was living in Hong Kong, she was politically supportive of the Republic of China, and paid regular visits. One of her visits was to attend the 10th October National Day Celebration in the 46th year of the Republic (1957), as a member of the Double Ten Delegation from the film and opera sectors in Hong Kong. Again she toured numerous military bases to sing for the troops.

Portrait of Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu (程硯秋)

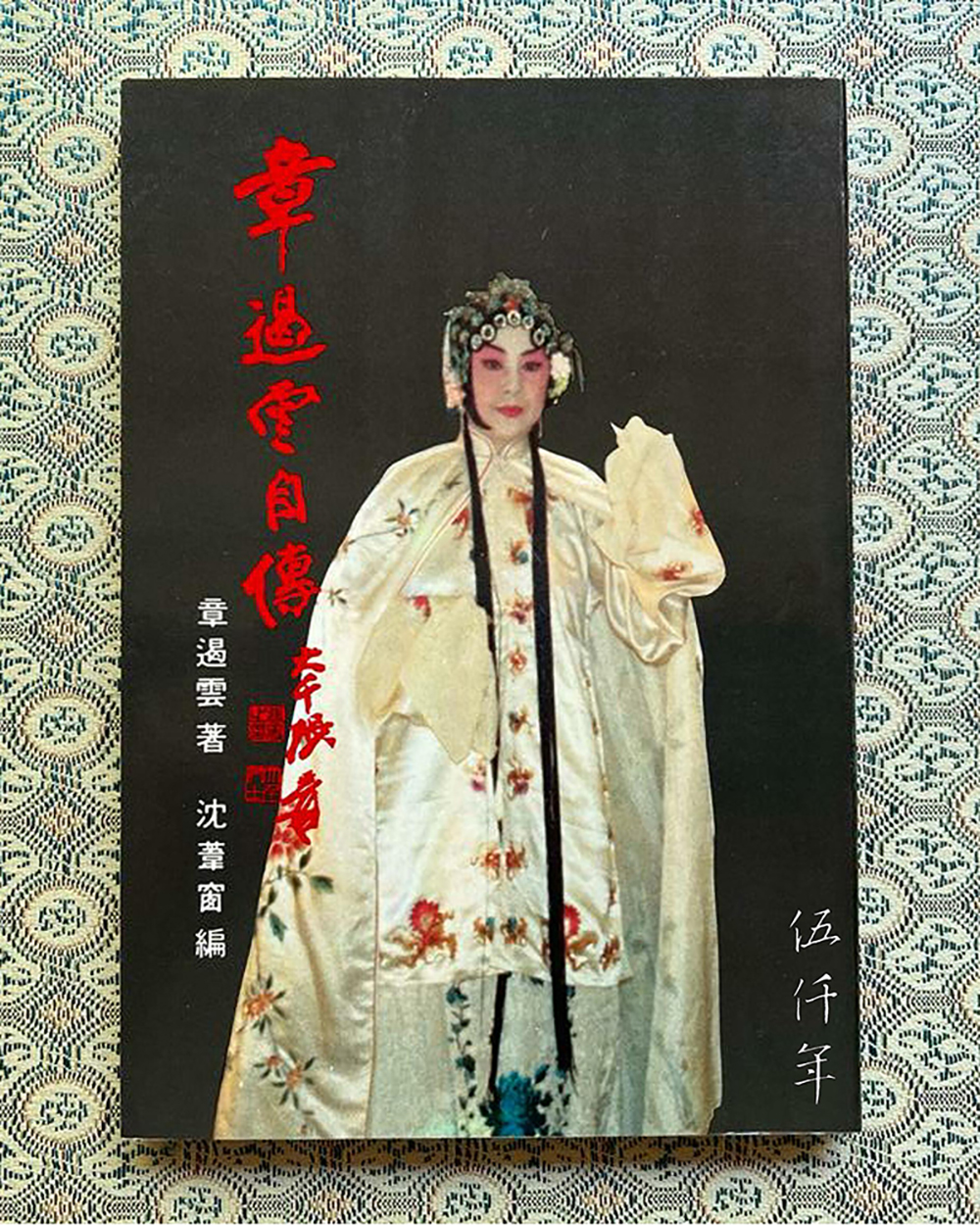

Front cover of Autobiography of Chang O-yün

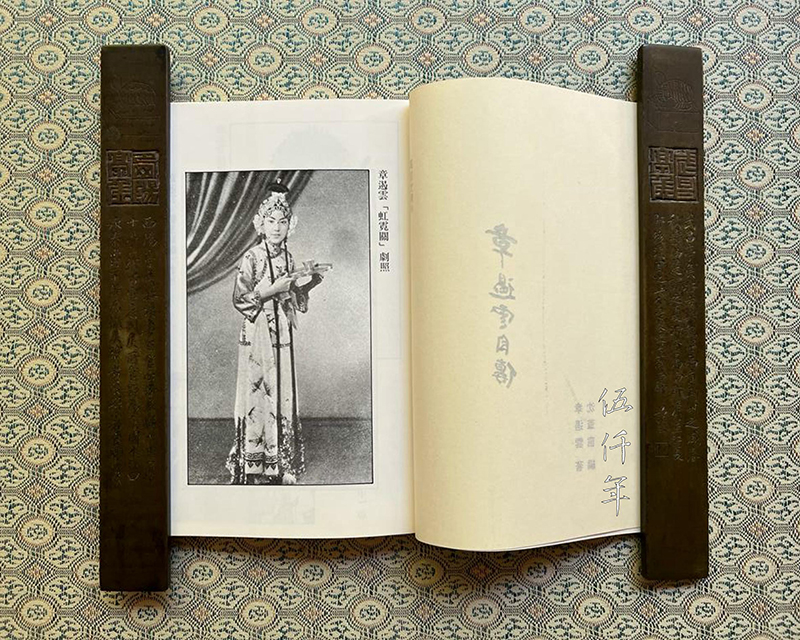

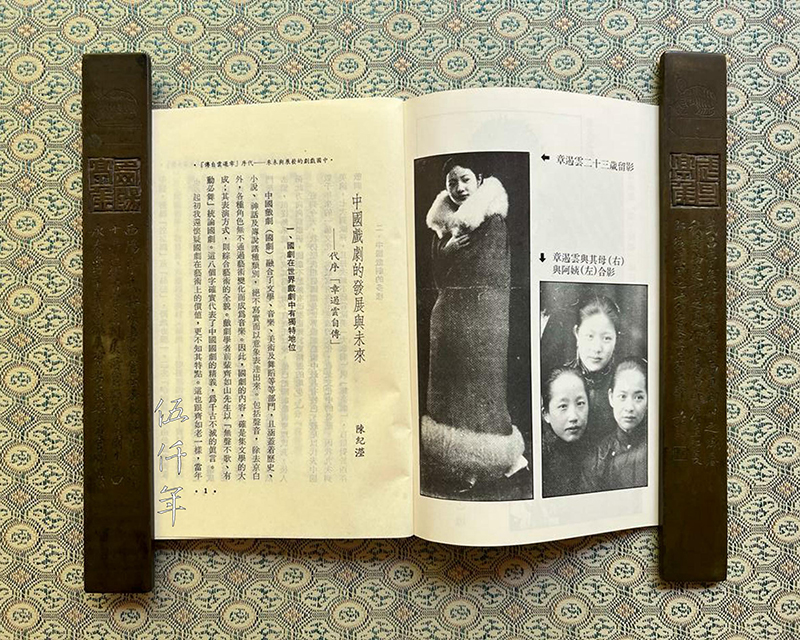

Inside page of Autobiography of Chang O-yün

Inside page of Autobiography of Chang O-yün

In March the 47th year of the Republic (1958), Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu (程硯秋) passed away in mainland China. A few months later, the communists appointed an intermediary in Hong Kong to invite Aunt Chang to return to the mainland, to take over the opera troupe of Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu. They offered a salary of 1,500 Yuan and a government allocated house. Aunt Chang promptly declined the offer. She recalled in the Autobiography of Chang O-yün:

“I knew if I just go, I would no longer have my personal freedom. Luckily I made the right choice by not going in rashly to be an ‘expropriate officer’. Because after this, the Cultural Revolution began. A little bourgeoisie like myself from Hong Kong, would for sure be purged to near death many times over. It is unlikely for me to be still alive to write this Autobiography ”.

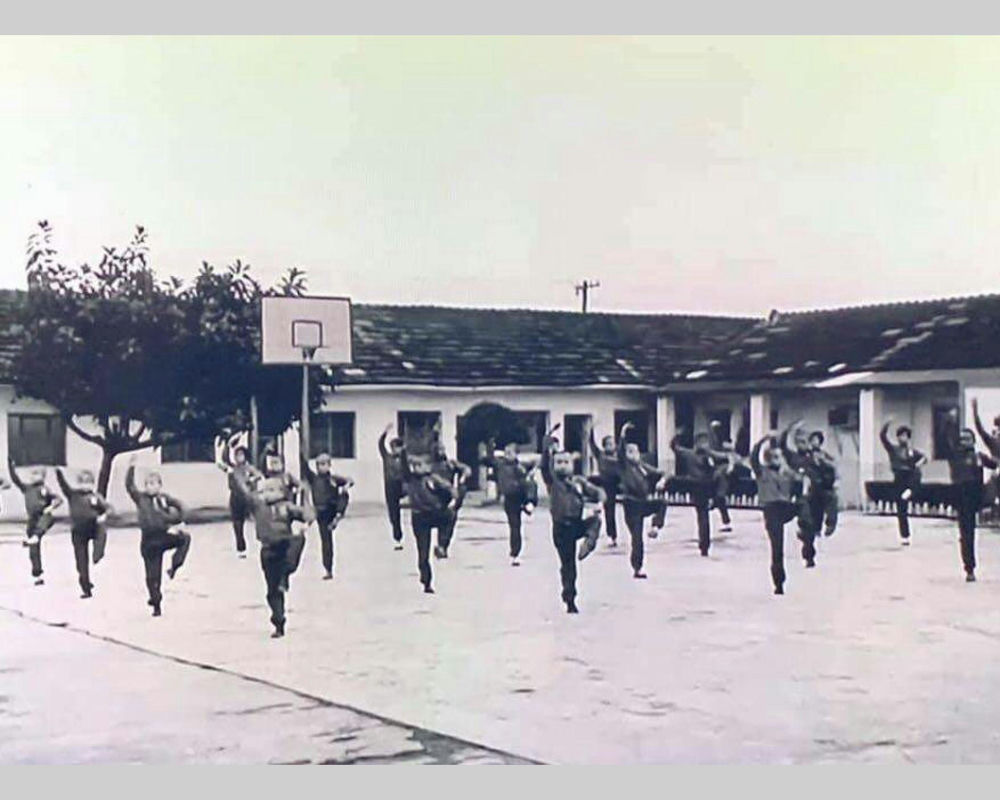

Ta-p’eng Opera School (大鵬劇校) under the administration of the Republic of China Air Force

In the 47th year of the Republic (1958), General Wang Shu-ming (王叔銘) made arrangements for Aunt Chang to settle in Taiwan. A government residence was allocated. Teaching positions were offered at the Ta-p’eng Opera School (大鵬劇校) under the administration of the Republic of China Air Force, and at the Lu-kuang Opera School (陸光戲校) under the administration of the Republic of China Army.

On 23rd August in the same year, the communists intensively shelled the islands of Kinmen and Matsu to prepare for an invasion, and the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis broke out. On 25th January the following year, Aunt Chang raised funds for the frontline troops in Kinmen and Matsu through a charity opera performance at the Chieh-shou Hall on Chung-hua Road in Taipei. Aunt Chang enjoyed a leisurely and carefree life in Taiwan. Comparing it with the Tophet life in mainland China at that time, she could only be gratified by her good fortune of escaping across the sea. Yet she was left in despair over the fate of her colleagues in the mainland who could not escape their imminent demises. She reminisced in the Autobiography of Chang O-yün:

“With the title of a teacher, I receive a monthly remuneration. For those students who follow the P’ing-chü School of Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu, they will all courteously visit me to receive instructions. Whenever I wish to perform, I can select the cast, and the opera troupe will oblige. Sometimes I stay in Taiwan a bit too long, every year or half, I will go to Hong Kong for pleasurable diversion. I have watched helplessly my many old colleagues on stage who stay in the mainland, one by one, they are purged to death. Clearly my choice for freedom at that time is absolutely right.”

Aunt Chang frequently travelled between Taiwan and Hong Kong. There were plenty of opera salons, opera dilettantes, opera aficionados in Hong Kong. They venerated Aunt Chang like the Tai Mountain and the Northern Star. Aside from taking part in the singing sessions of the opera salons, she also performed periodically on stage.

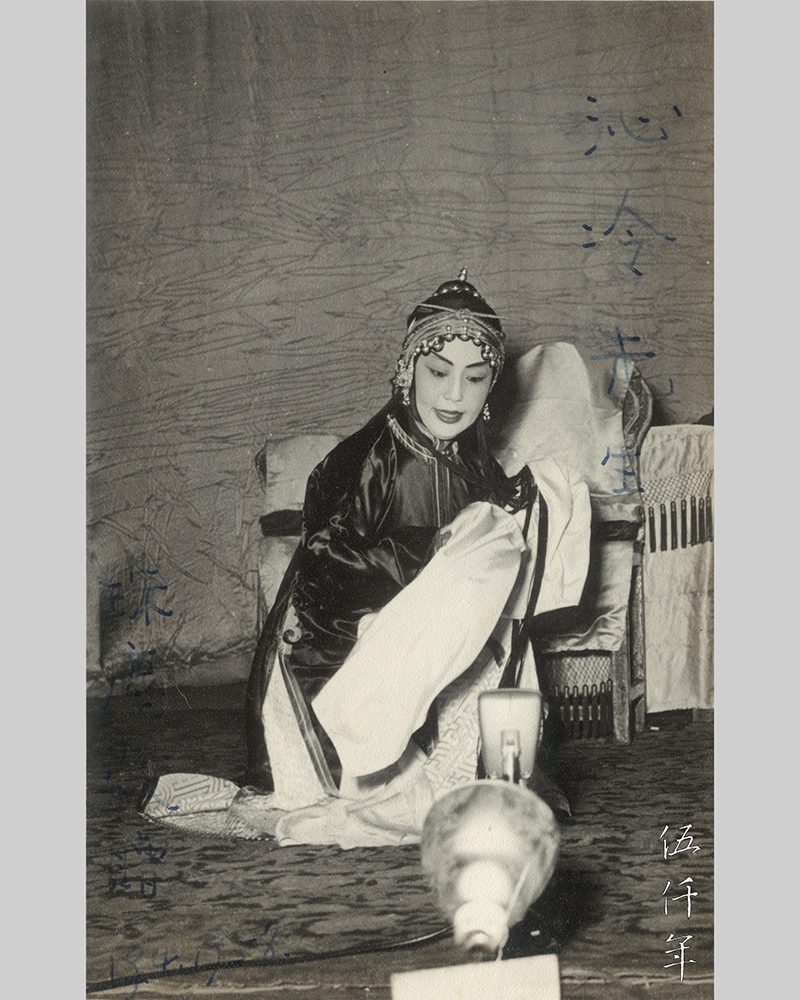

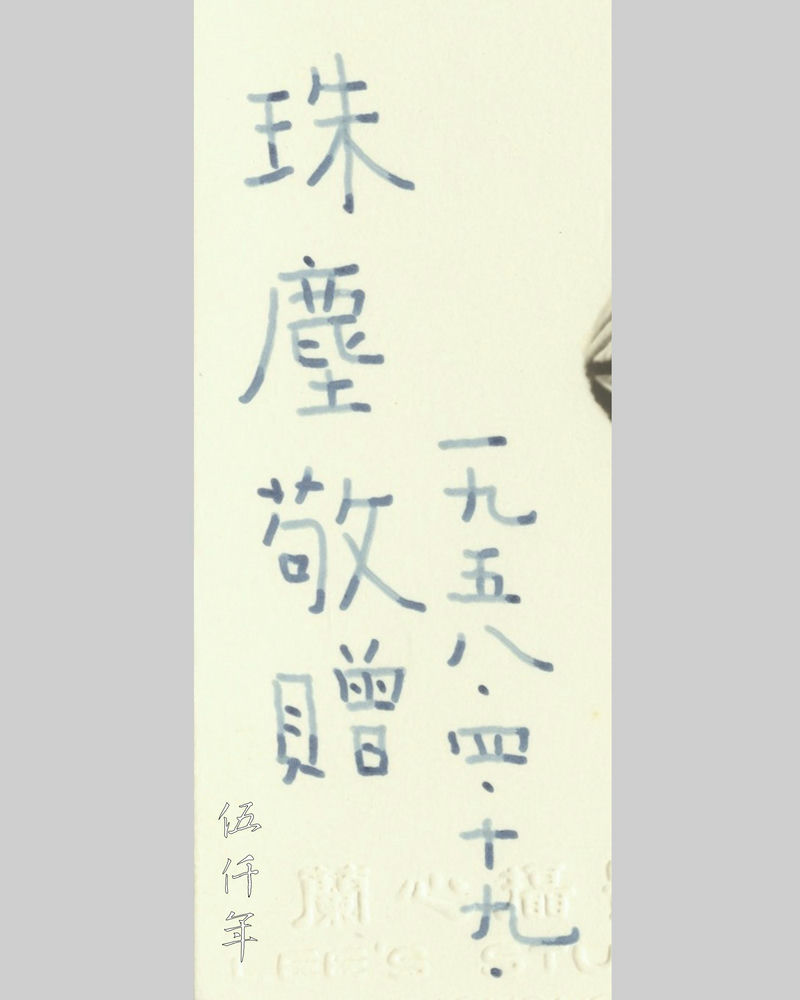

Aunt Chang O-yün presented an inscribed photograph to Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

Aunt Chang O-yün presented another inscribed photograph to Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

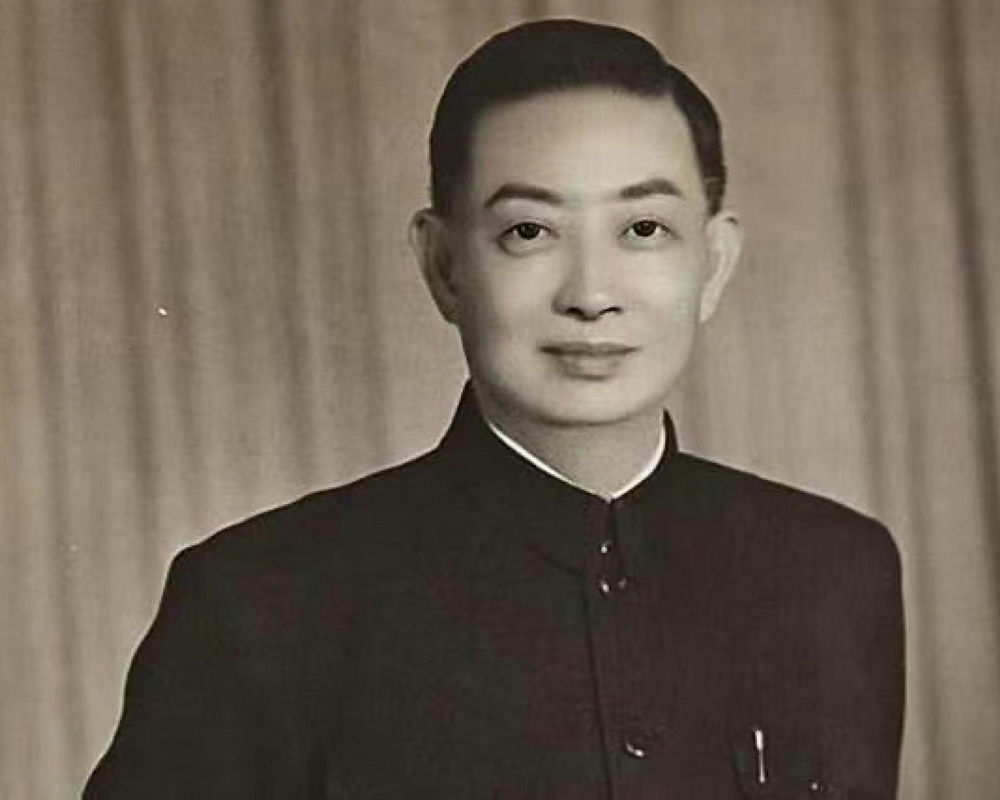

My late father, Mr. Soong Hsün-leng, was an opera dilettante of the P’ing-chü School of Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu. His sojourn in Hong Kong at that time enabled him to know Aunt Chang well. At one time she presented him with two inscribed photographs. The inscription on one photograph reads: “To Mr. Hsin-leng (心冷), respectfully presented by Chu-ch’en (珠塵). 19th April 1958.” The inscription on another photograph reads: “To Mr. Hsin-leng (心冷), respectfully presented by Chu-ch’en (珠塵).” Hsin-leng was the hao of Mr. Soong Hsün-leng, and Chu-ch’en was the hao of Aunt Chang. These inscriptions by an illustrious soprano of an earlier era are to be treasured.

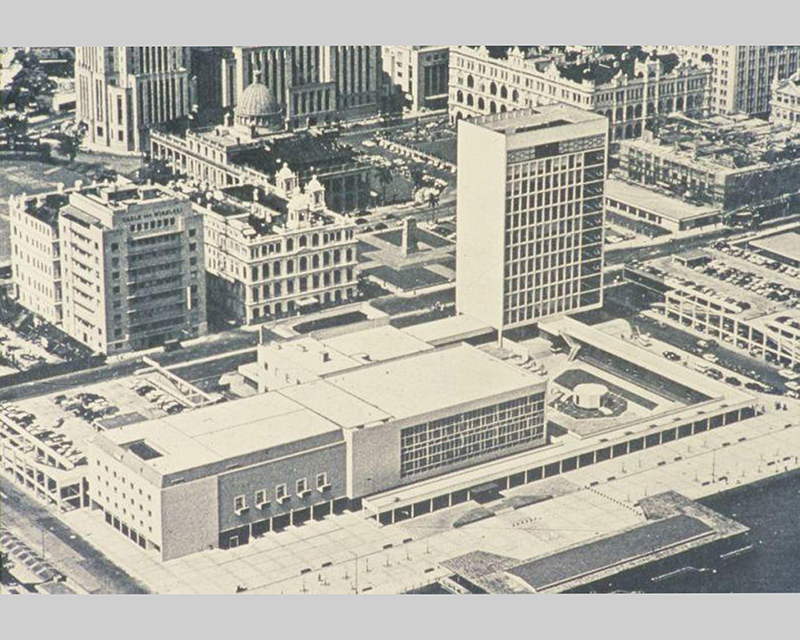

Hong Kong City Hall in the 1960’s

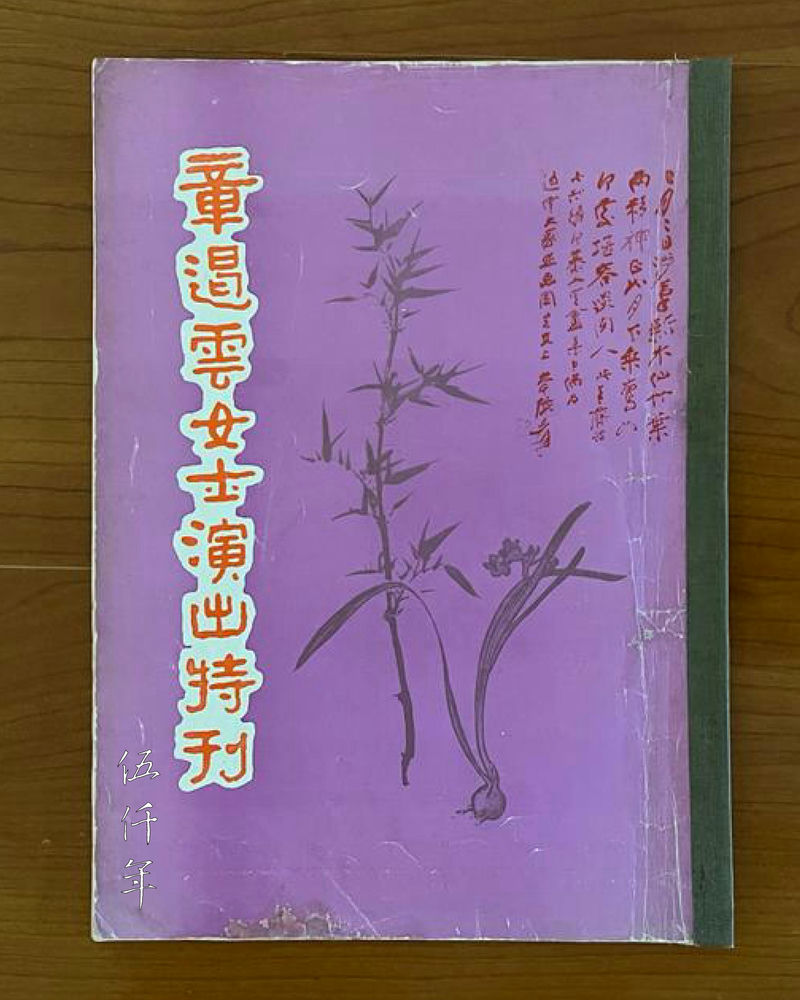

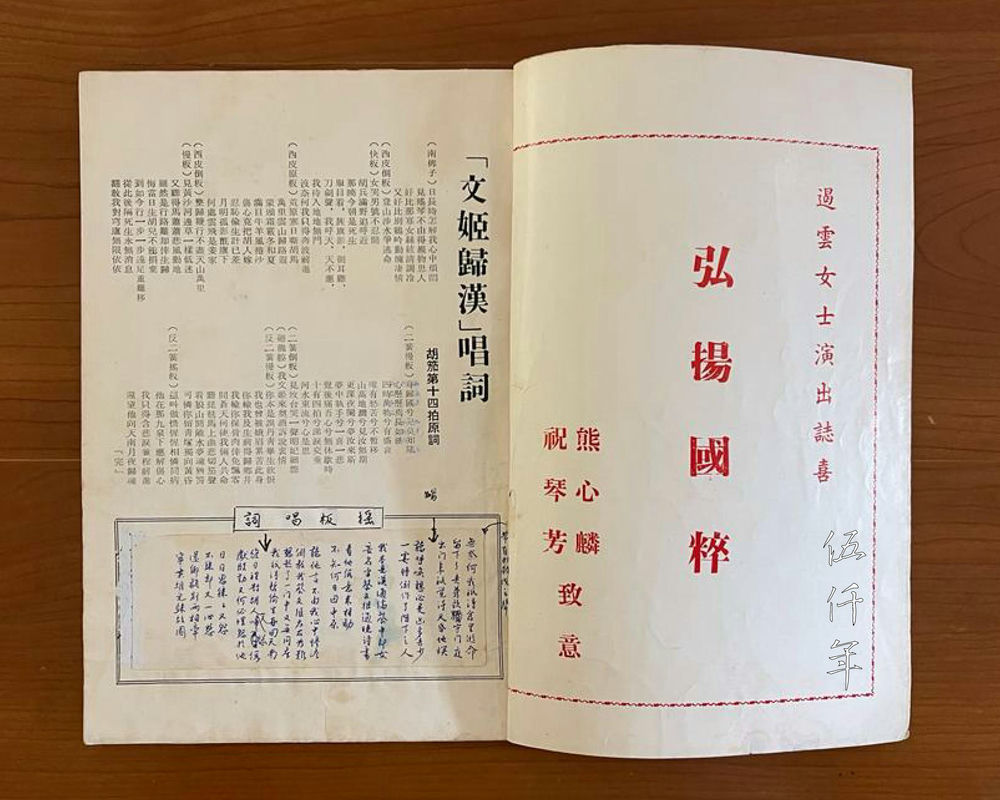

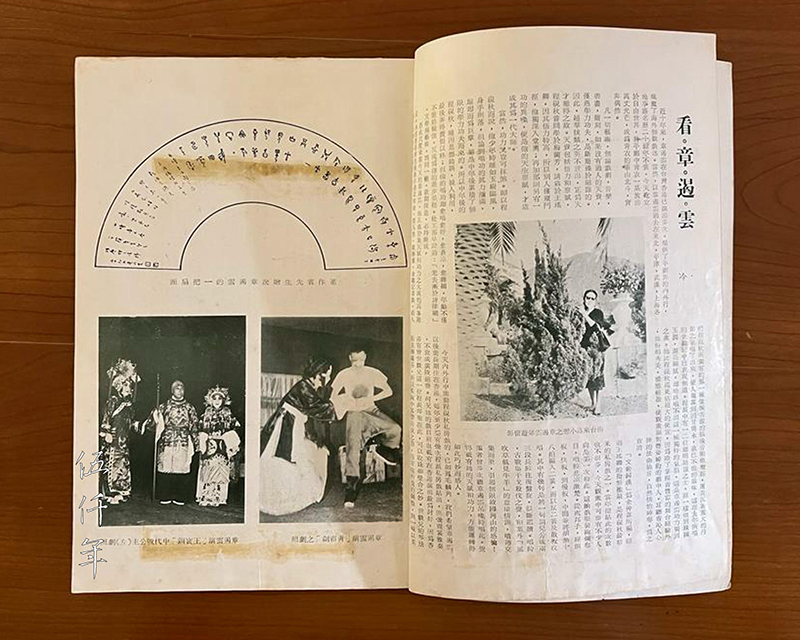

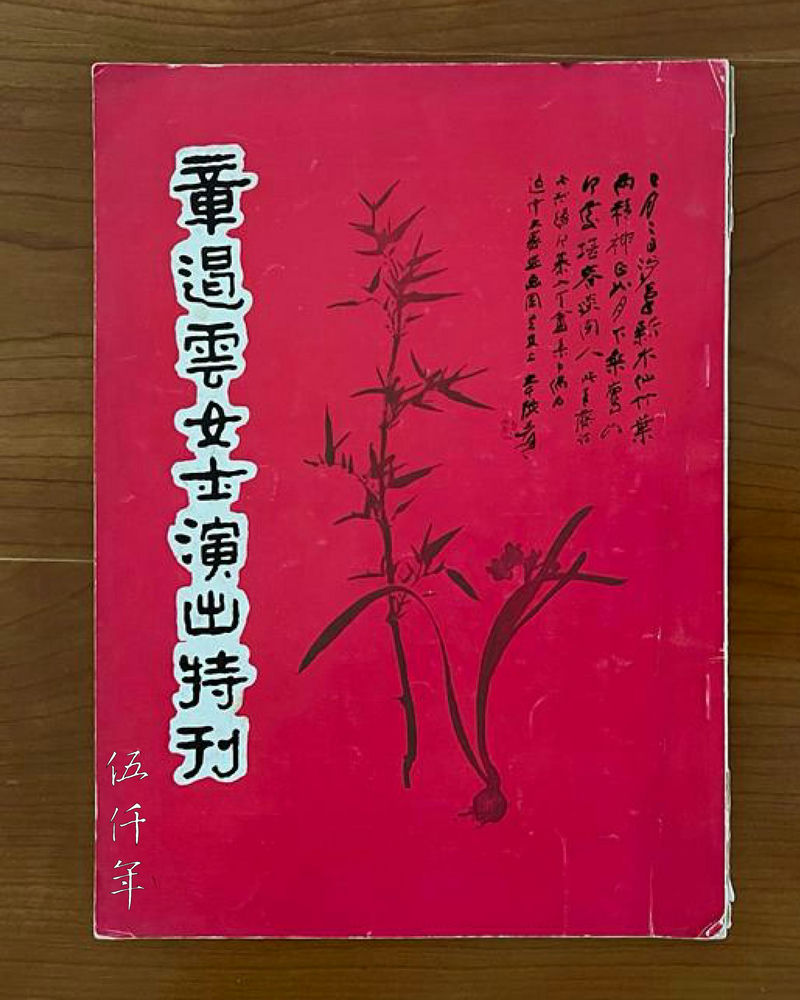

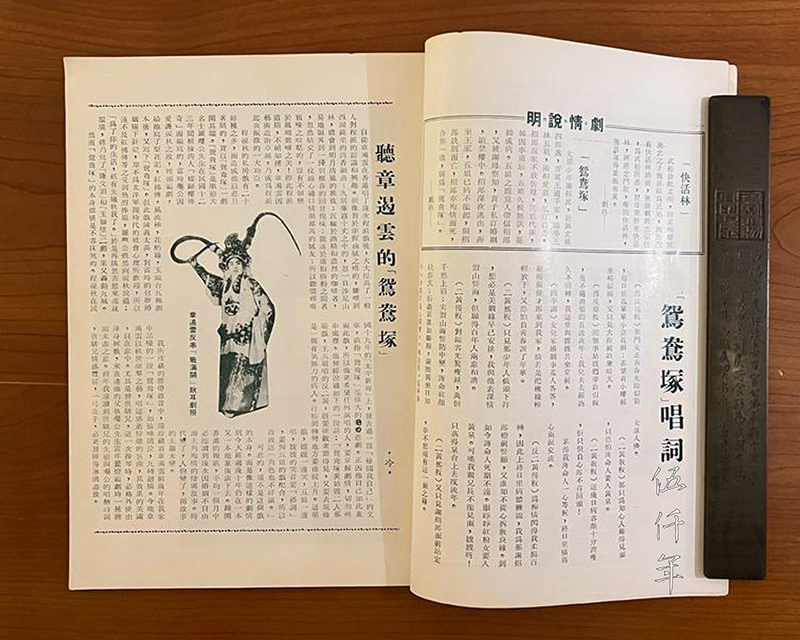

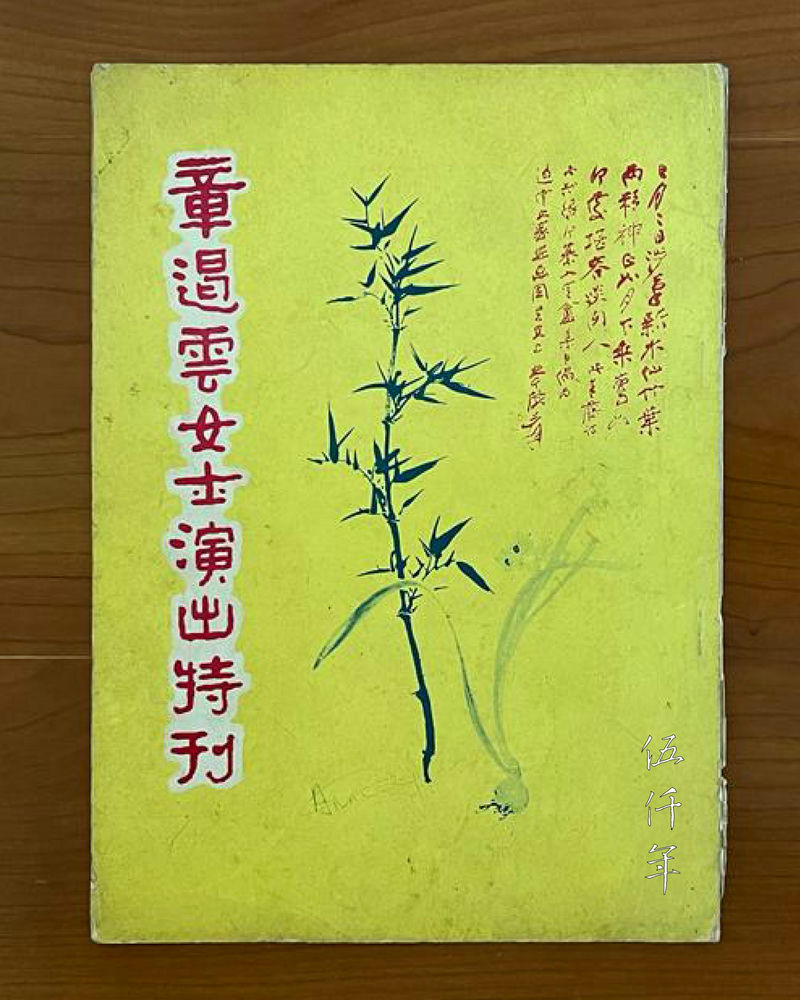

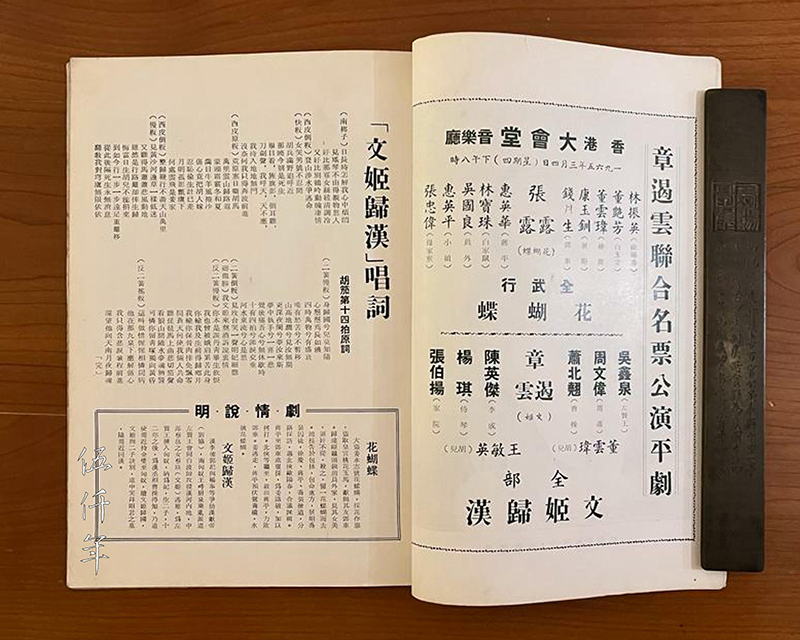

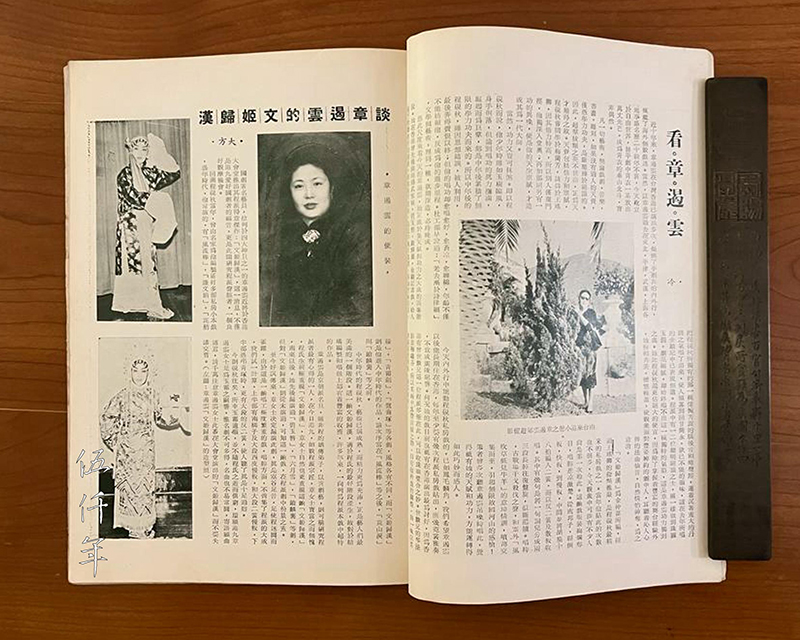

Opera programmes were always produced for Aunt Chang’s numerous performances in Hong Kong, and my father often wrote articles behind the librettos to expound her artistry. Three different opera programmes are to be found in my house. They use the same cover title Special Issue of Ms. Chang O-yün’s Performance, only their colours are different. The first opera programme is for the performance of Wen-chi Returning to Han (文姬歸漢) which took place at 8pm on Thursday 4th March 1965, at the concert hall inside the Hong Kong City Hall. The article Observing Chang O-yün by Mr. Soong was published in the programme. The second opera programme is for the performance of Yüan-yang chung (鴛鴦塚) which took place at 8pm on Wednesday 4th August 1965, at the concert hall in the Hong Kong City Hall. The article Listening to Yüan-yang chung by Chang O-yün, written by Mr. Soong was published in the programme. The third opera programme is for the performance of Mu-yang chüan (牧羊卷), also known as Chu-hen chi (硃痕記), which took place at 8pm on Monday 24th April 1967, at the concert hall in the Hong Kong City Hall. The article Observing Chang O-yün by Mr. Soong was reprinted in the programme.

Front cover of the opera programme for the performance of Wen-chi Returning to Han (文姬歸漢) on 4th March 1965 in Hong Kong

Inside page of the opera programme for the performance of Wen-chi Returning to Han (文姬歸漢) on 4th March 1965 in Hong Kong. Mr. Soong Hsün-leng copied the Yao-pan (搖板) libretto on the lower section of the page

Inside page of the opera programme for the performance of Wen-chi Returning to Han (文姬歸漢) on 4th March 1965 in Hong Kong. The article Observing Chang O-yün written by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng was printed on the recto

Front cover of the opera programme for the performance of Yüan-yang chung (鴛鴦塚) on 4th August 1965 in Hong Kong

Inside page of the opera programme for the performance of Yüan-yang chung (鴛鴦塚) on 4th August 1965 in Hong Kong. The article Listening to Yüan-yang chung by Chang O-yün written by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng was printed on the verso

Front cover of the opera programme for the performance of Mu-yang chüan (牧羊卷) on 24th April 1967 in Hong Kong

Inside page of the opera programme for the performance of Mu-yang chüan on 24th April 1967 in Hong Kong. Picture of on Chang O-yün performing in the opera Fen-ho Wan is on the verso

Inside page of the opera programme for the performance of Mu-yang chüan on 24th April 1967 in Hong Kong. Libretto of Wen-chi Returning to Han was printed on the verso

Inside page of the opera programme for the performance of Mu-yang chüan on 24th April 1967 in Hong kong. The article Observing Chang O-yün written by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng was reprinted on the recto

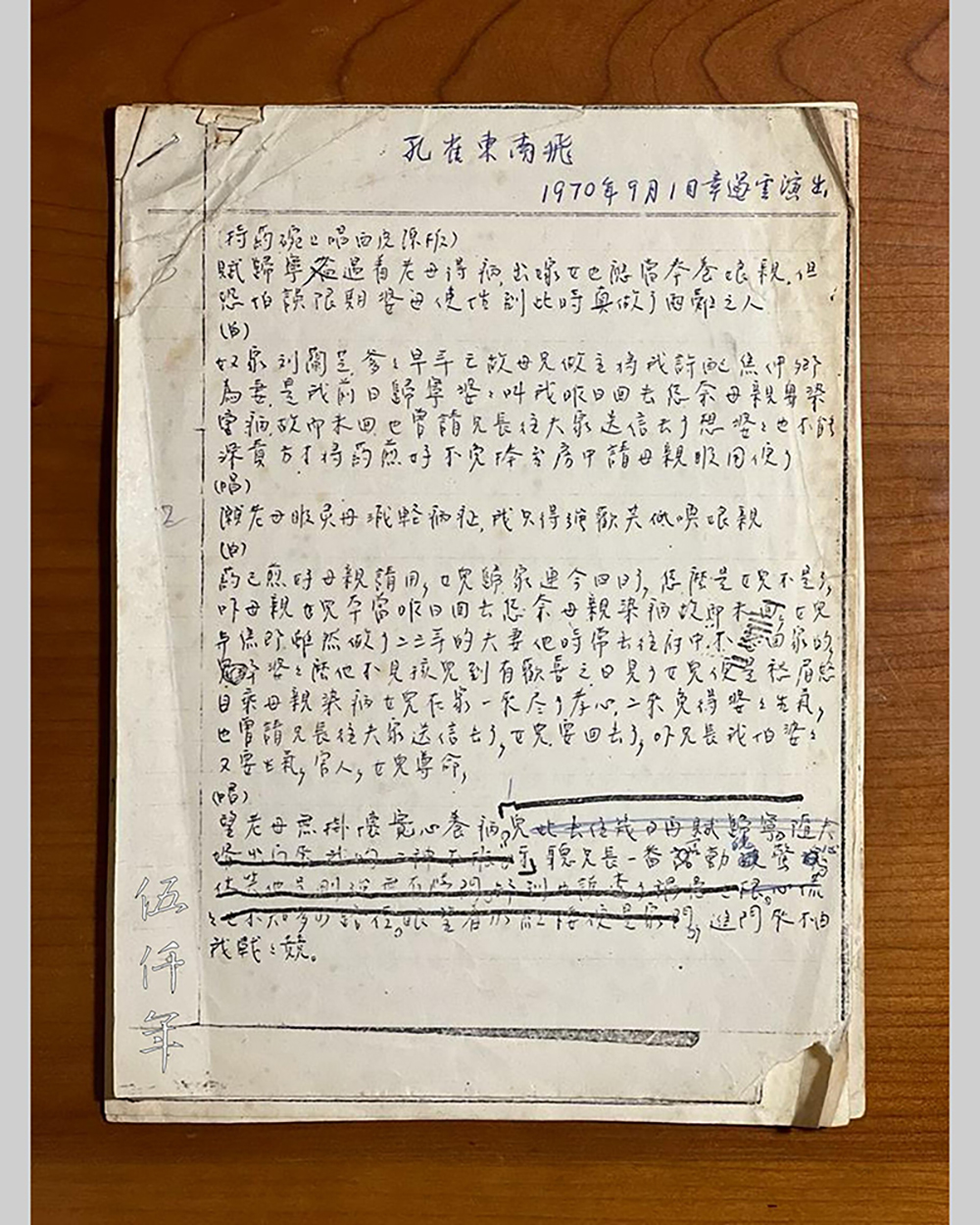

I also have a six page xerox set of handwritten libretto. At the top of the first page, my father inscribed: “K’ung-ch’üerh tung-nan fei (孔雀東南飛). Performed by Chang O-yün on 1st September 1970.” Thus we knew that this opera was performed by Aunt Chang in Hong Kong too. There is no indication of the authorship of these handwritings. There are many scribbles and deletions. One may conjecture they are the handwritings of Aunt Chang.

Mr. Soong Hsün-leng inscribed the libretto of K’ung-ch’üerh tung-nan fei (孔雀東南飛). The opera was performed on 1st September 1970 in Hong Kong

My father treasured his many private live recordings of Aunt Chang’s singings, some taken during the singing sessions of the opera salons and some taken during the stage performances in Hong Kong. They are now likely to be the only extant recordings of those sessions and performances. I hereby present the live recording of her singing in Wen-chi Returning to Han (文姬歸漢), performed on 4th March 1965 in Hong Kong nearly sixty years ago. This recording is offered not just to earn timely applause, more so it is wished that it can be preserved forever, to avail the revival of P’ing-chü. For the world to better appreciate the virtuosity of Aunt Chang, it will certainly be rewarding to read Observing Chang O-yün by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng.

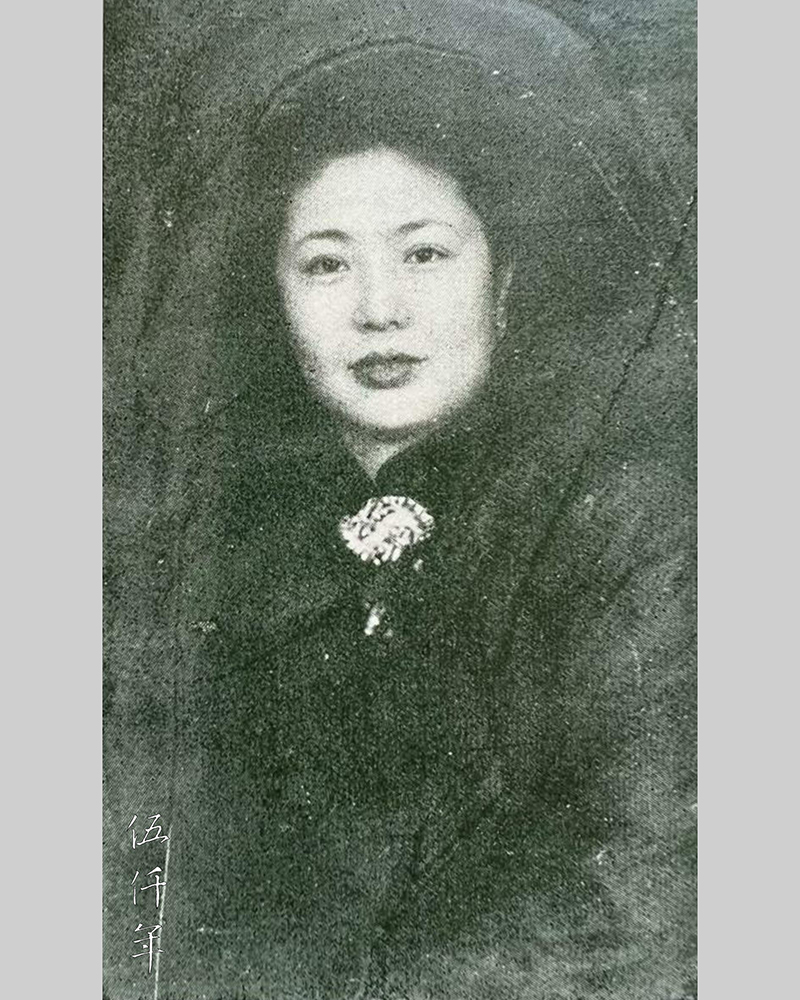

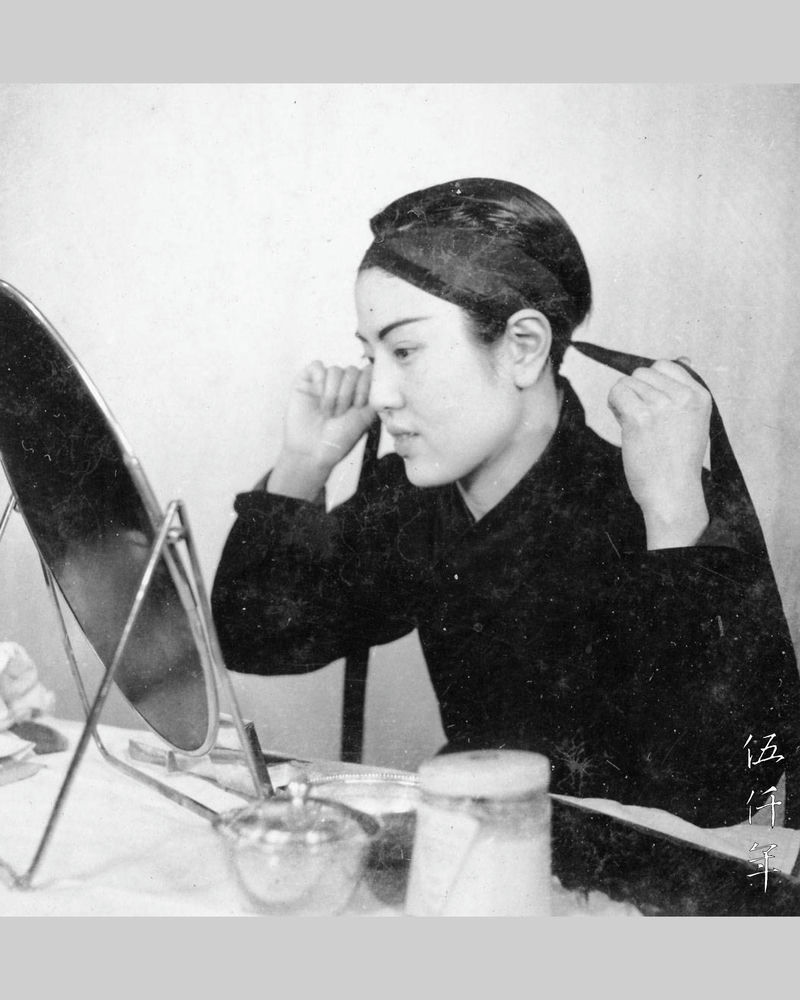

Portrait of Aunt Chang O-yün

Observing Chang O-yün (章遏雲), by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng, 1965

In the last ten years, Chang O-yün (章遏雲) has given many performances in Taiwan and Hong Kong. She is adored by the professionals and dilettantes of Peking opera, and lionized by countless overseas enthusiasts. Of course in the past, Chang O-yün enjoyed a stellar reputation uninterrupted for over twenty years in north-east China, Peking, Tientsin, Wuhan, Shanghai and other places. Now she stands tall in the Free World, radiating splendour on behalf of the dan (旦) role in Peking opera. Her eminence in the dan role, is analogous to the grandeur of the T’ai Mountain and the brilliance of the Northern Stars. This is not attained by chance.

For all arts, be it opera, music, calligraphy, painting, sculpture, if one does not possess exceptional talent, by relying on studiousness and travail alone, it is impossible to reach artistic zenith. For this reason, whenever peerless talent fails to appear at opportune moment, it is because genius is rare to come by. Talent includes apprehension and natural endowments. At one time, Ch’eng Yen- ch’iu (程硯秋 1904-1958) studied under Mei Lan-fang (梅蘭芳 1894-1961), and sought teachings from Wang Yao-ch’ing (王瑤卿 1881-1954). As he was especially adept at apprehension, when others only glimpsed the entrance path, he alone entered deep into the inner chamber. Additionally he was gifted with a different voice that could realize a particular effect. This was his natural endowment. These made him a master of an era.

Of course, his travail should certainly not be denied. In the case of Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu, when he was young, his virtuosity and appearance were distinguished, like a jade tree in the breeze, his body movements were precise. Yet regarding the genuine brimful clout of his vocal prowess, from which he rose to become a maestro, it came into being at middle age, after he had accumulated immeasurable sum of studiousness and travail. After middle age, Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu made mistake with his political judgement, and was exploited by others, eventually dying of remorse. However as for his voice, the more he sang the better it became, ever more desolate, ever more lingering. Not only was age not an impediment for him, instead it was a milestone of his advancement. Tu Fu (杜甫 712-770) had earlier said: “At my old age, the prosody of my poetry gradually becomes more refined.” For literature and art, the principles are identical, to aspire to reach its pinnacle, one must wait to mature through age.

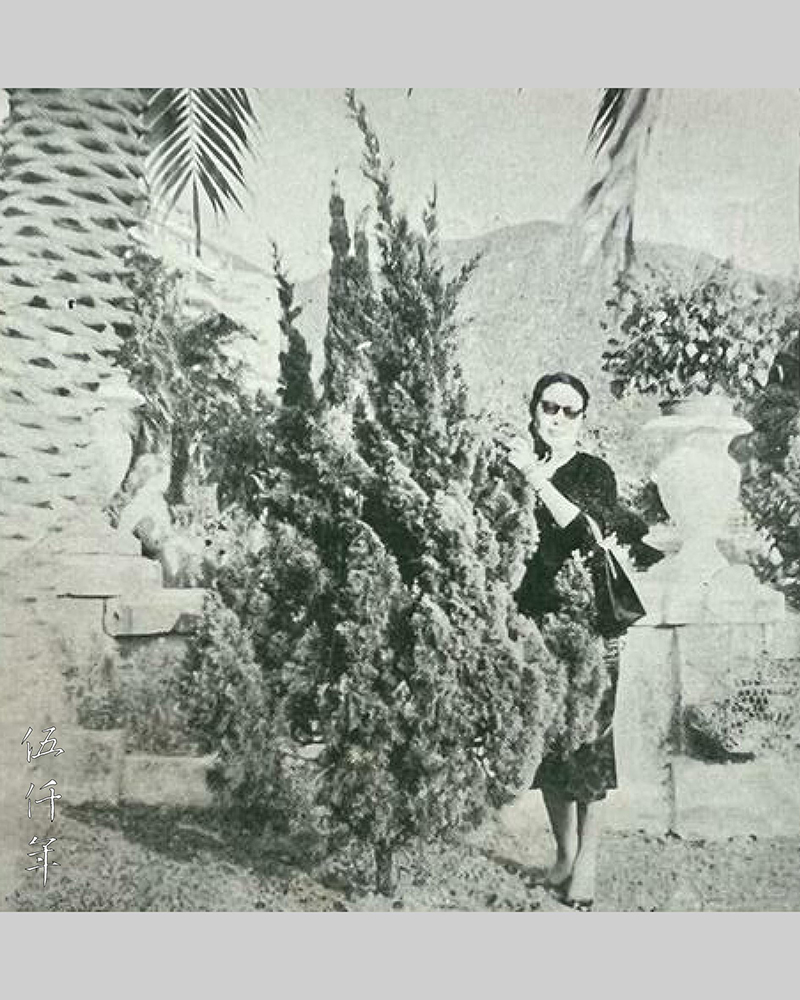

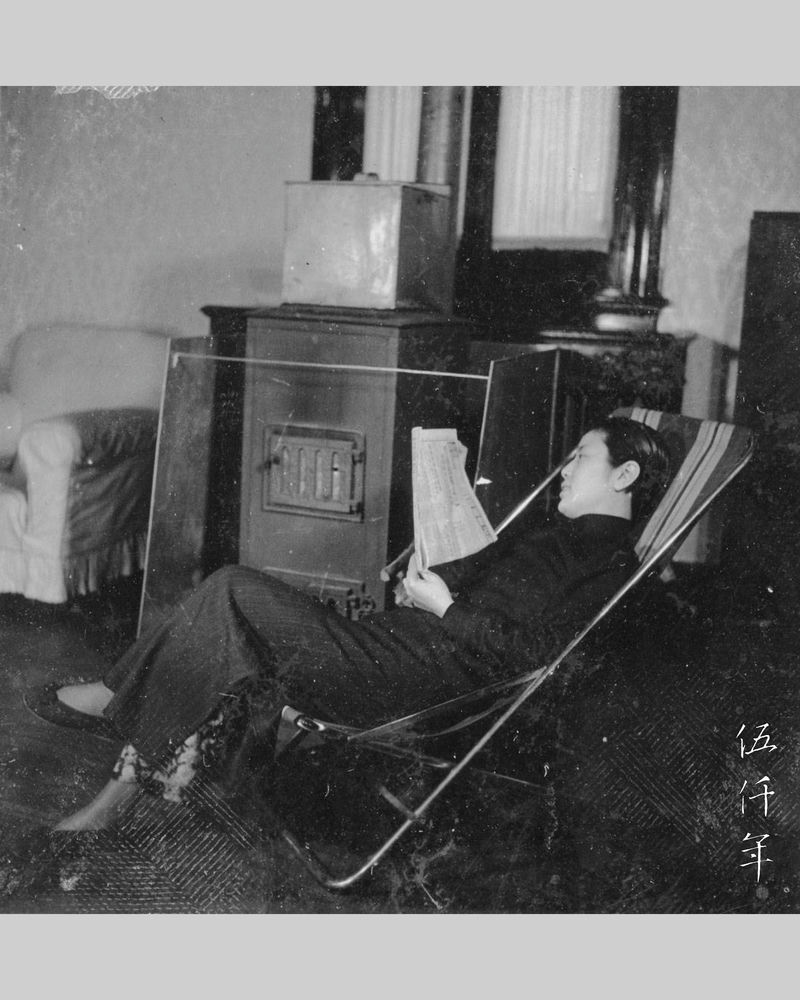

Aunt Chang O-yün on a visit to Hong Kong

Using this yardstick to observe Chang O-yün of today, she is at her peak, having synthesized natural endowment and proficiency. In Hong Kong, she has consecutively performed the operas Wu-chia P’o (武家坡), Pi-yü-tsan (碧玉簪), So-lin-nang (鎖麟囊), Chin-so-chi (金鎖記) and others. The audience has been left with one impression, the more they listen, the more alluring it becomes. The hardest and most precious, is that in recent years, with her broader vocal range, built upon by persistent training and fluid adaptation, she has attained the unique voice of Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu, a kind of sorrowful, bitter, raspy, behind the brain, olive pitch (low-high-low pitch). This she sings through the full energy of the cinnabar field. The audience acquires the flavour of a lingering after taste, a timelessness, an irresistible implicit charm, perfectly demonstrated in her performance of the opera Chin-so-chi last year. There are one or two of the brightest in the Ch’eng school, though likewise achieve polish, clarity, sonority and exquisiteness, yet they cannot express this unique spirit and appeal in their singings. This is the distinctive skill of Chang O-yün. She is in a far more advantageous position than Ch’eng Yen- ch’iu, besides the wealth of stage experience at her disposal, her face is elegant and beautiful, her posture is agile. The audience meets a character in the opera whose comportment is feminine and graceful, listens to a musical classic with angelic voice that touches the heart. It is natural to succumb in such a joyful and moving moment.

Wen-chi Returning to Han (文姬歸漢) was composed by Chin Chung-sun (金仲蓀 1879-1945). After tutorship and scrutinization by Wang Yao-ch’ing, it became one of the finest pieces in the private opera repertoire of Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu. In those years, he only performed this piece a few times. Many of today’s audience are now probably listening to this for the first time. The costume of this opera is magnificent and dazzling, the vocal is sorrowful and impassioned. The melodies start from nan-pang-tzu (南邦子), to tao-pan (倒板), k’uai-pan (快板), man-pan (慢板), in midway, Wu-chia shih-pa- p’ai (胡笳十八拍) was compiled into erh-huang (二簧), ending with fan-erh-huang (反二簧) and san-pan (散板). A few sentences are segmented into two or three long vocals that circulate repeatedly, purportedly halting then resuming. In the vocal, the clatters and crashes of shields and spears on an ancient battlefield, the imagery and mood of wind swept grass exposing cows and sheep in the northern frontier, all infuse into a splattering mist, arousing endless lamentations over the mountains and rivers of our occupied country! This author has heard Chang O-yün singing this piece in rehearsals many times, and feels that only her natural endowment and proficiency, can produce such ingenuity, subtlety, and passion.

Today, among the professionals and dilettantes of Peking opera, to find someone who is qualified to handle the private opera repertoire of Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu, is as rare as feather from a phoenix or horn from a unicorn. We hope Chang O-yün can permanently live in Hong Kong in the future, so that every year there can be at least a few performances of the private opera repertoire of the Ch’eng school. Perhaps such unworldly costume and music will not meet the same fate as the ancient zither music Kuang-ling-san (廣陵散), to be lost forever. Moreover at this moment, her most appealing performances can only be undertaken in Hong Kong, because here is my friend Tseng Shih-chün (曾世駿), the sage of the stringed musical instrument hu-ch’in (胡琴). It is a perfect artistic union like matching pearls or adjoining jade discs. The way Shih-chün plays the hu-ch’in originates from the artistry of Mu T’ieh-fen (穆鐵芬), it is gentle and graceful, with a touch of light, sharp vigour. This comes from the noble quality of his character. Comparing this with the common hu-chin music that is amiable and eager to please, it is from a different world.

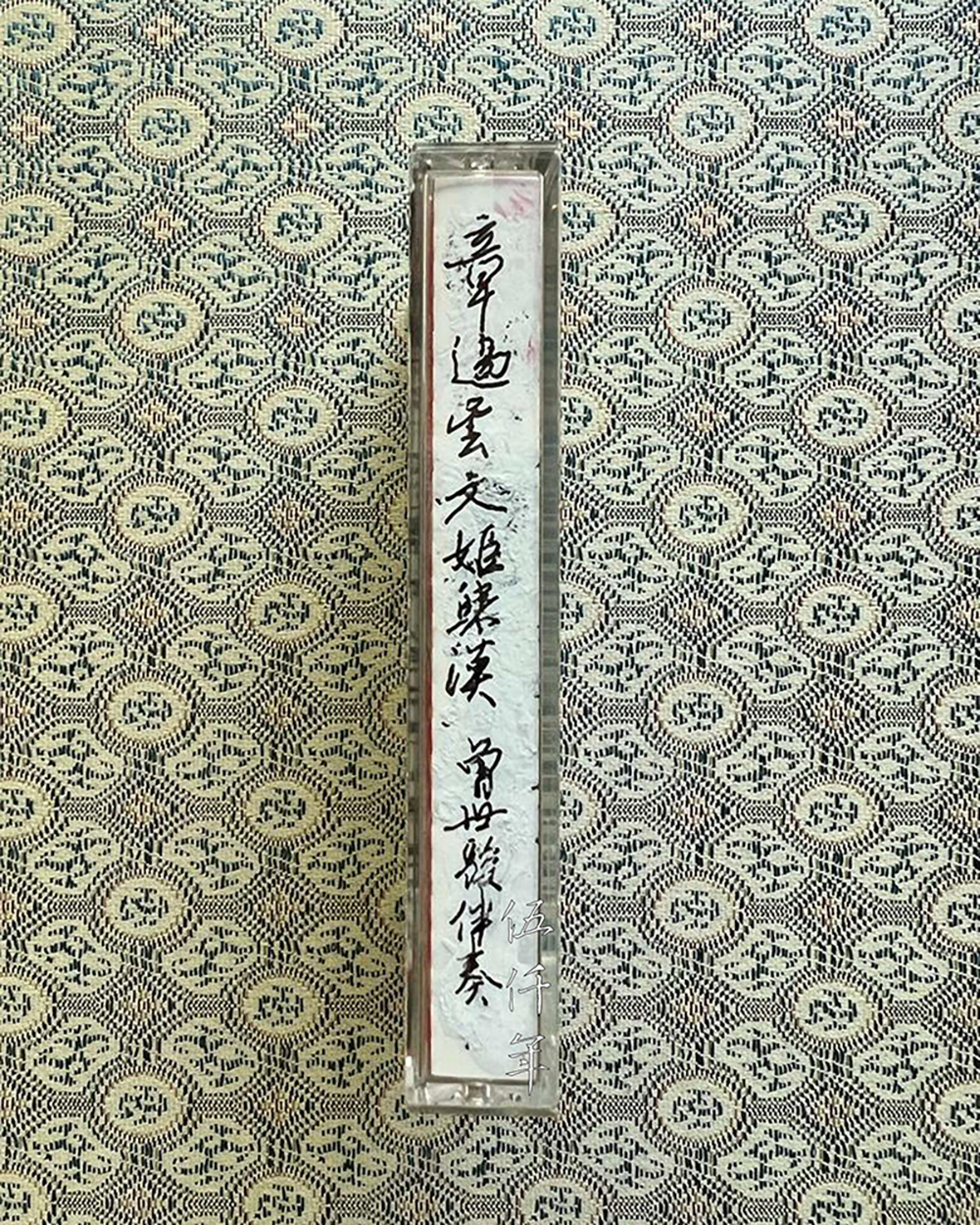

Front view of cassette case containing tape recording of Wen-chi Returning to Han (文姬歸漢), with inscription inside by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

Side view of cassette case containing tape recording of Wen-chi Returning to Han (文姬歸漢), with opera title inscribed by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

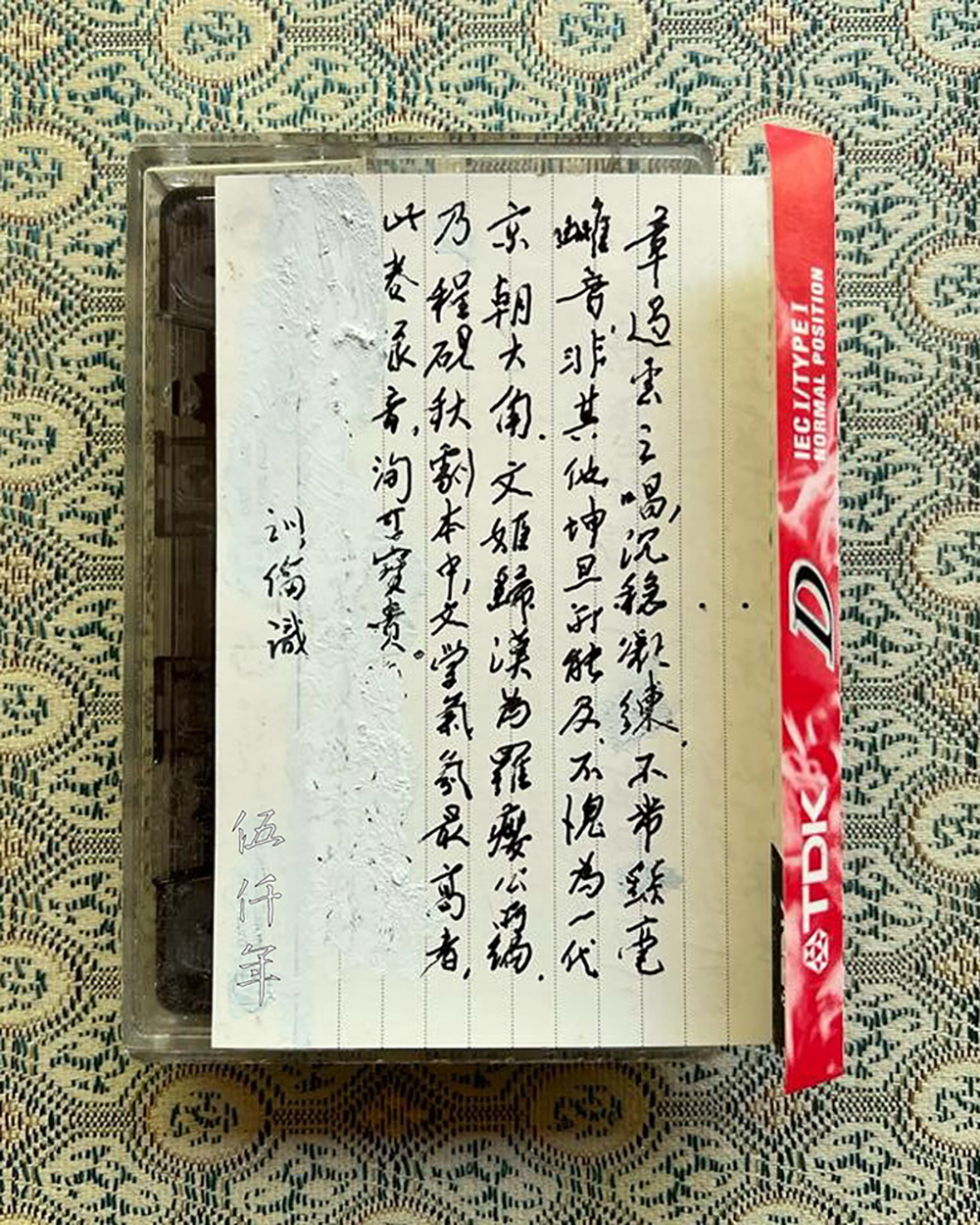

Back view of inscription sheet inside cassette case containing tape recording of Wen-chi Returning to Han

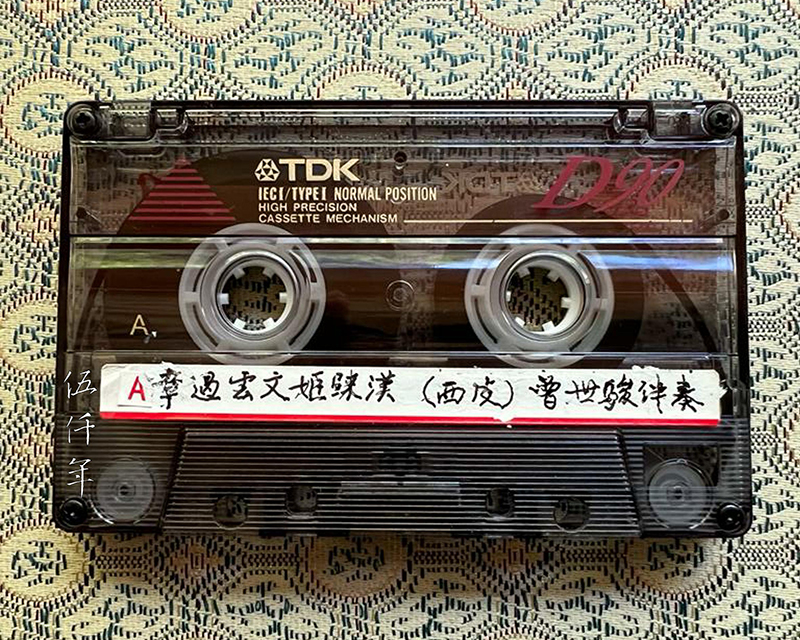

Side A of cassette tape recording of Wen-chi Returning to Han

Side B of cassette tape recording of Wen-chi Returning to Han

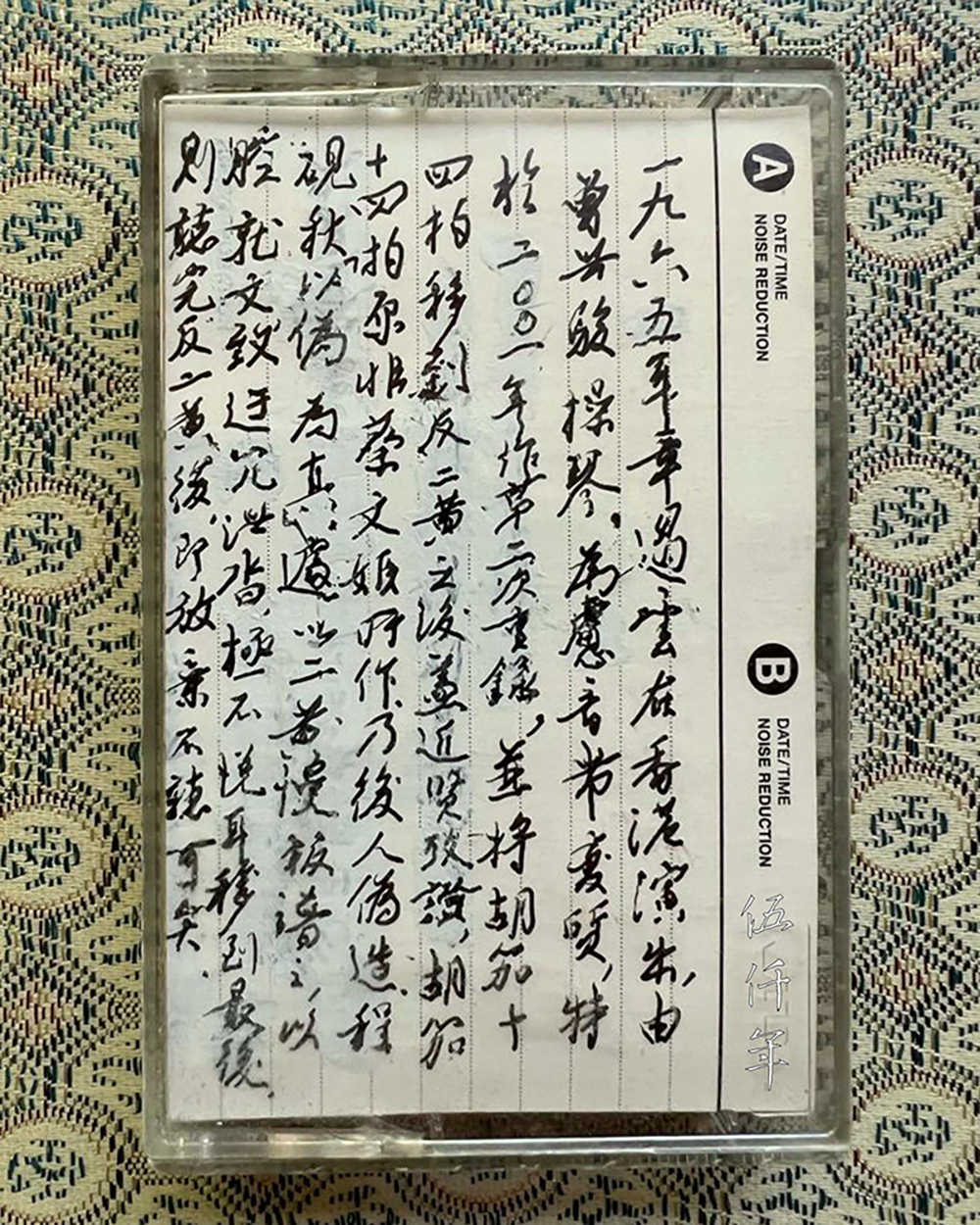

Cassette Recording of Wen-chi Returning to Han (文姬歸漢) with Inscription on J-Card by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng.

Inscription reads:

“In 1965 Chang O-yün (章遏雲 1912-2003) gave a performance in Hong Kong. Tseng Shih-chün (曾世駿 1915-1993) played the musical string instrument hu-ch’in (胡琴). I was anxious that the original reel tape might deteriorate, so I specially made a cassette tape copy in 2001. I transfered the section of Hu-chia shih-ssu-p’ai (The Fourteenth Stanza of a Nomad Flute 胡笳十四拍) to follow behind the section of fan-erh-huang (反二簧), because recent men of eminence had researched and concluded that the fourteenth stanza of the poem Hu-chia shih-pa-p’ai (The fourteenth Stanza of a Nomad Flute 胡笳十四拍) was not written by Ts’ai Wen-chi (蔡文姬) from the Eastern Han dynasty in the first place. It was ghostwritten by someone from a later period. Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu (程硯秋 1904-1958) assumed that the forged was genuine, and applied the tune erh-huang-man-pan (二簧慢板) to the lyrics. Since the tune has to accommodate the lyrics, this section of the opera becomes unrealistic and disorderly, estremely unpleasant to the ears. By transfering this section to the end, one can perhaps give up this final part after listening to the section of fan-erh-huang.

Wen-chi Returning to Han (文姬歸漢), performance by Chang O-yün, hu-ch’in by Tseng Shih-chün.

The vocal by Chang O-yün is steadfast and precise, there is not a hint of feminine voice, other female opera singers are incomparable. She is certainly worthy of a great opera singer from the old capital. The opera Wen-chi Returning to Han was composed by Lo Ying-kung (羅癭公 1872-1924). Of all the opera scripts of Ch’eng Yen-ch’iu, this is foremost in literary ambience. It is a recording to be dearly cherished.

Recounted by Hsün-leng.”

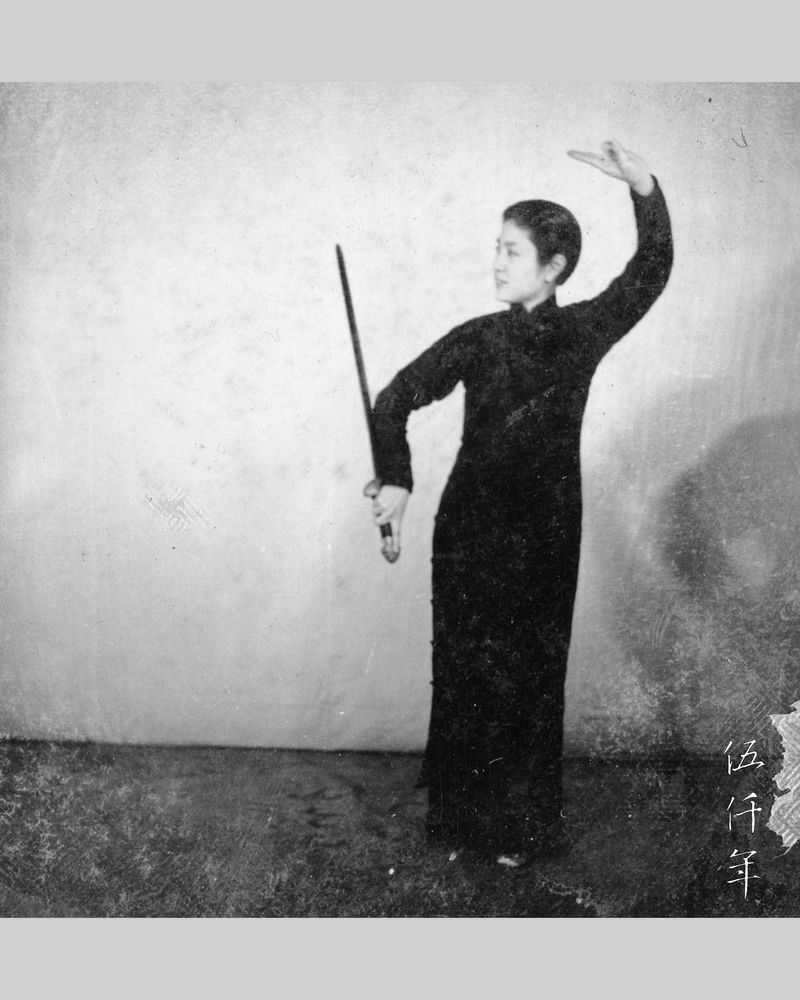

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Libretto of Wen-chi Returning to Han

Nan-pang-tzu (南梆子)

While the day is long,

Who knows my heart’s torment?

Gazing at the zither

Reminds me of no one but him.

Like a widow plucking the strings,

Lonely tune and desolate sound.

Like the call of a parting crane,

Harrowing and forlorn.

Hsi-p’i-tao-pan (西皮倒板)

To scale the mountains,

To cross the rivers,

To flee to vie for life.

K’uai-pan (快板)

How unbearable

The cries and shrieks

Of men and women.

Barbarian soldiers

Throng the field,

Shouting in hot pursuit.

Who can tell how we end today?

Will it be life or will it be death?

Raise the eyes,

See the silhouette of an army,

Flex the ears,

Hear the clanging of the swords.

I rail at Heaven

and gets no reply,

I wait on Earth

and gains no entry,

I can but resign

to keep running onward.

Hsi-p’i-yüan-pan (西皮原板)

On a cold ravaged plain

The barbarian horses neigh.

Endless mountains capped in clouds,

Return journey is far beyond.

In my sleep,

Frosts and sleets,

Winters then to summers.

In my eyes,

Cows and sheep,

Wind sweep up the sand.

I grieve my marriage to a Hun,

A misconceived plan

Of shame of wasted life.

A bright moon,

A fur covered tent,

A solitary shadow underneath.

Which one of these windborne clouds,

Can I truly call it home?

Hsi-p’i-tao-pan (西皮倒板)

Ready the horse for homeward trek,

Endless miles of T’ien-shan range.

Man-pan (慢板)

Look at the yellow sand,

The riverside grass,

Downcast alike.

Hear again lonesome horse,

Dismal wind thump the earth.

Even this trial of a journey,

Just lucky to return alive.

I repent the births of Hun children,

So unbearable to abandon.

Today every step with every step,

Too laden too heavy to carry.

From now a parting from life to death,

Never ever any more news.

In turn I long for this humble tent,

So reluctant to say goodbye.

Original lyrics of Hu-chia shih-ssu-p’ai (The Fourteenth Stanza of a Nomad Flute 胡笳十四拍)

Erh-huang-man-pan (二簧慢板)

I have returned to my country,

Alas! The children know not the trail.

My heart is in suspense,

Empty as in lengthy hunger.

All life in the four seasons,

Alas! Brim and wane.

Only woe and gloom,

Alas! Cannot be a fraction moved.

Mountains are tall and plains are broad,

Alas! We may never ever meet again.

In the depth of night,

Alas! I dreamt you came at last.

In my dream I held your hands,

Alas! There was joy and there was sorrow.

When I woke my heart was wrenched,

Alas! There is no rest from this pain.

By the fourteenth stanza,

Alas! Tears and mucus souce my face.

The eastbound river clears it all,

Alas! Except the yearning in my heart.

Erh-huang-tao-pan (二簧倒板)

In front of the ritual table at the tomb,

I cried and uttered your name Empress Ming.

Hui-lung-ch’iang (迴龍腔)

I, Wen-chi, is here to offer ritual wine

To vent my inner feelings.

Fan-erh-huang-man-pan (反二簧慢板)

You were from the start

Framed by a painter’s portrait

And paid the price for life.

I have been likewise

Afflicted by my own beauty

And haggard to this day.

You lose out to me,

For in this lifetime

I have come back home.

I lose out to you,

For you shielded

Your children from adrift.

I question Heaven

Why make our fates entwine?

Hear the Chinese lute on horseback

And the mournful music from heathen flute.

Look at Lang-shan mountain,

Listen to Lung-shui river,

A startled soul even in a dream.

So pitiful it has been

Leaving a grass covered tomb,

Facing sunset all by yourself.

Fan-erh-huang-yao-pan (反二簧搖板)

Hear this fitting sentence

To empathize with each other

Over one shared karma.

Now in the underworld

She is bound to discern sorrow.

What else but to hold

My heart-rending tears

Hastening my journey onwards.

May her soul travel home

Towards the southern sky

In a full moon night.

Yao-pan (搖板)

At home I failed to see

The early ominous sign

Of cicada captured by mantis bug.

Wondering over the noises

Of killings and of fightings.

With no choice

I flee in panic,

Handing the house

To an old retainer,

A lonely guardian.

In my flight,

Only sightings

Of dismal sky

Of bleak earth.

Listen to the bawls,

Likely malice lies ahead.

Spur of a moment,

A prisoner I became.

Before all this,

I am daughter of Ts’ai Yung,

The learned scholar.

My name is

Ts’ai Wen-chi,

Erudite in the Classics.

Look at his hypocrisy to comfort me!

When will I return to central China?

Listen to his words,

My heart is just dismal.

Ts’ai Wen-chi is myself in a bind,

Recalling none of my family is by me.

Try I will to survive awhile,

To return again to the southern sky.

Laughs and tears through the day,

Altogether insincere with a Hun.

Eager offerings of solicitude,

Why then blame him instead?

Everyday I think of homecoming,

Yet homecoming makes me resent.

If I relinquish homecoming now,

My heart will then be in suspense.

Homecoming and separation are both entwined,

I rather forfeit the children of Hun

To return to my country once more.

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

Photograph from the personal collection of Aunt Chang O-yün

The nom de plume Chu-ch’en (珠塵) signed by Aunt Chang O-yün