The contemporaries and intimate friends of Mr. P’u Ju (溥儒先生) have long passed away. Today, if one wishes to discover a few unknown tales about Mr. P’u, the only way is to look to the writings of his close friends in the past. Mr. Soong Hsün-leng, the tz’u poet, at one time published an article titled The Former Prince P’u Ju in Ta-jen Magazine from Hong Kong, in June of the 59th year of the Republic (1970), seven years after the death of Mr. P’u. It described in detail some of their artistic and refined pastimes during their meetings in Tokyo and their gatherings in Hong Kong. This year is exactly the sixtieth year of the Chinese sexagenarian cycle since Mr. P’u passed away, the Chinese-Heritage Virtual Museum now reissues the article to commemorate one of the finest scholars in Chinese history.

Curatorial and Editorial Department

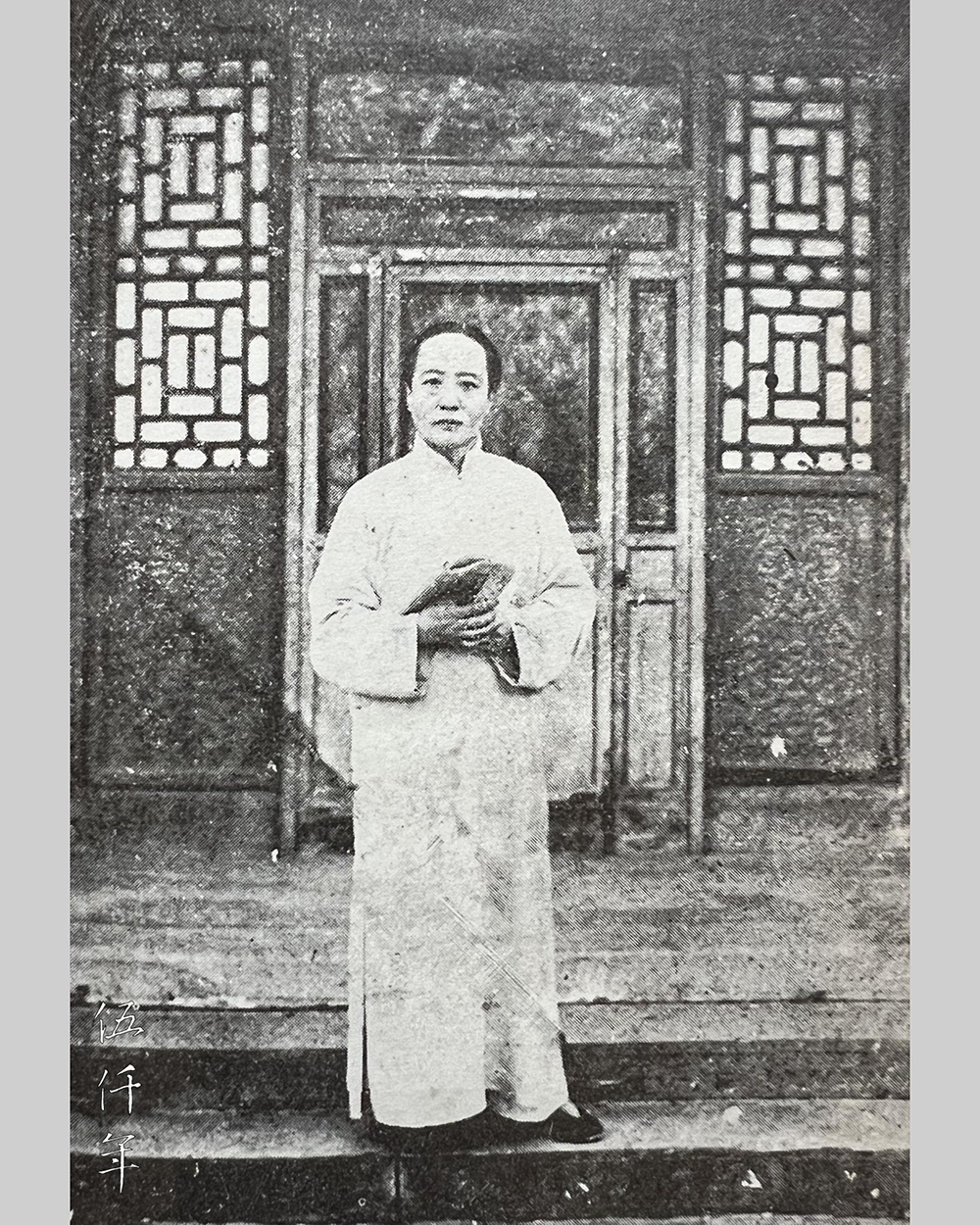

Portrait of Prince P’u Ju. Photograph courtesy National Taiwan Normal University

The ancestry and painting virtuosity of Mr. P’u Ju (溥儒先生 1896-1963) have been discussed by many and are known to even more. This account here is merely my personal impressions of Mr. P’u. He had friends everywhere, and if a good number of them compile their personal impressions into a book, chronicling the outstanding thoughts and exceptional deeds of this master painter of our time, it will certainly add to our exalted memory of him.

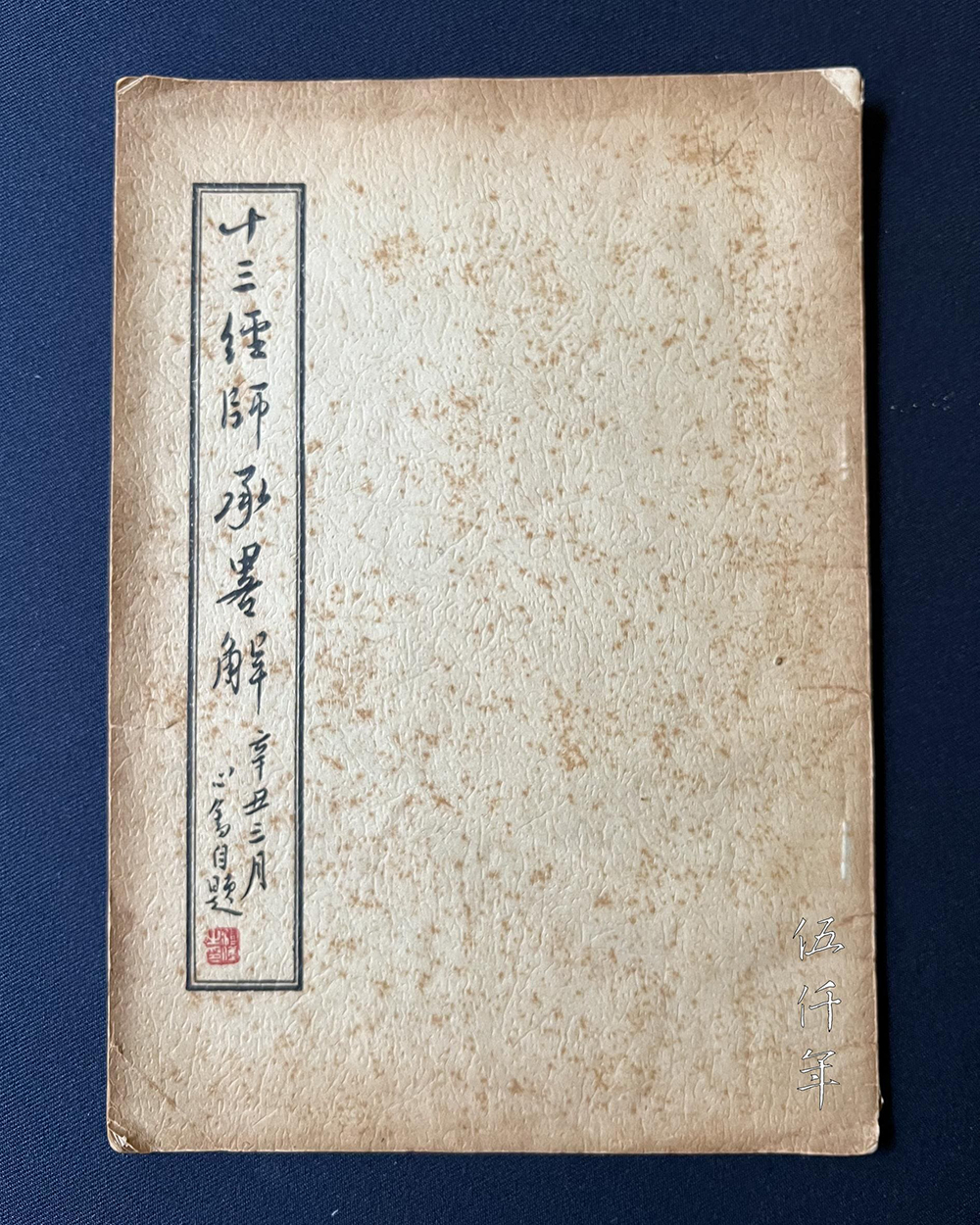

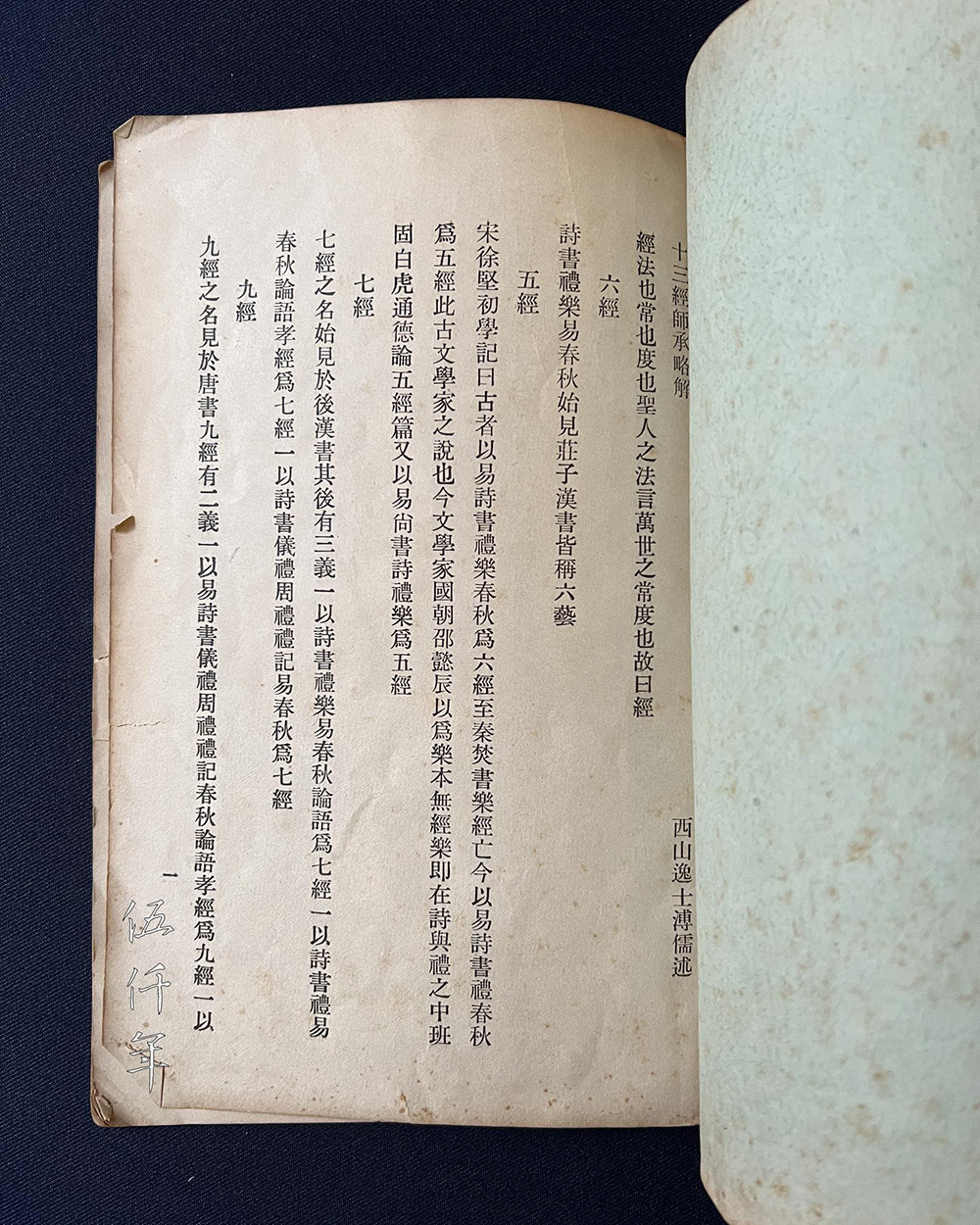

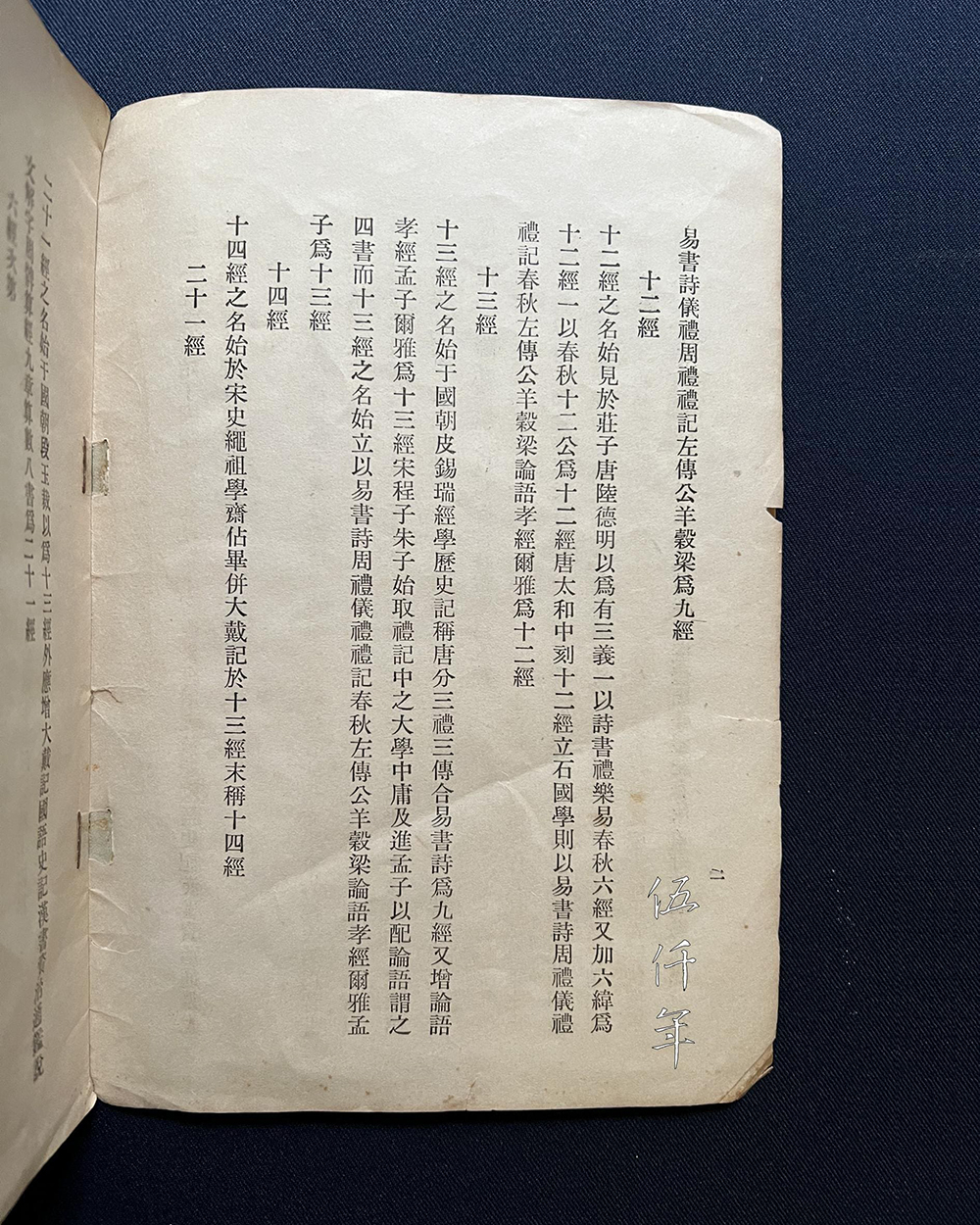

I call him the master painter of our time. Should Mr. P’u knew from the netherworld, he would surely be displeased. In fact, he considered himself a scholar of the Chinese Classics. He conducted himself in compliance with the principles of morality and diligently implemented them through actions. This was his basic approach to life as well as to teaching. Painting, in his mind, was merely the least of some frivolous skills. His writings include A Collection of Verifications on the Essences of the Four Books (四書經義集證) and A Brief Exposition of the Transmissions of the Thirteen Classics (十三經師承略解). The former is a monumental work which I have not had the opportunity to read, the latter he kindly gifted me. It is a slim volume that provides a concise overview of the origins and developments of the Thirteen Classics, much like a foundation book with questions and answers outlining the general knowledge of classical studies used in universities or specialized institutions.

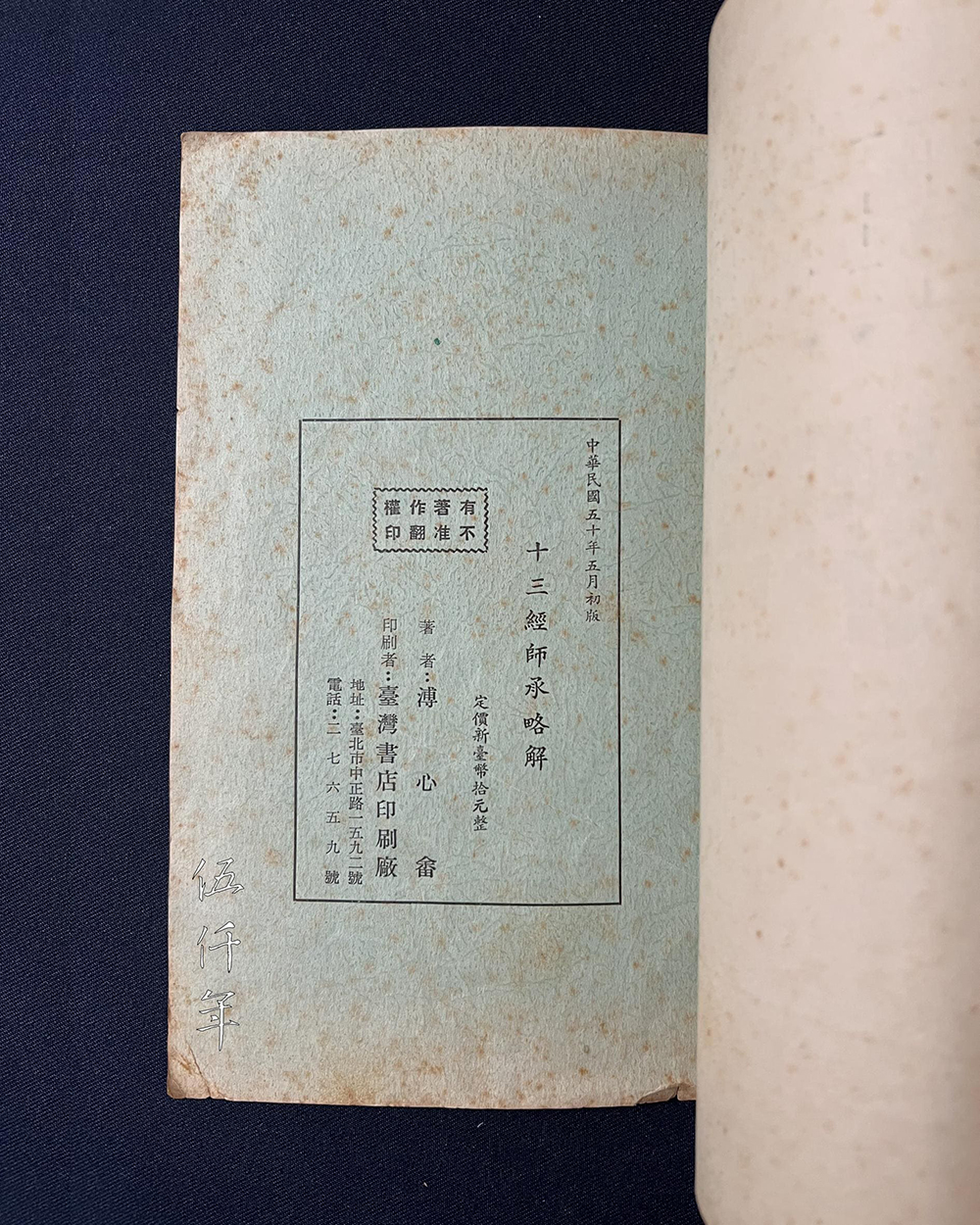

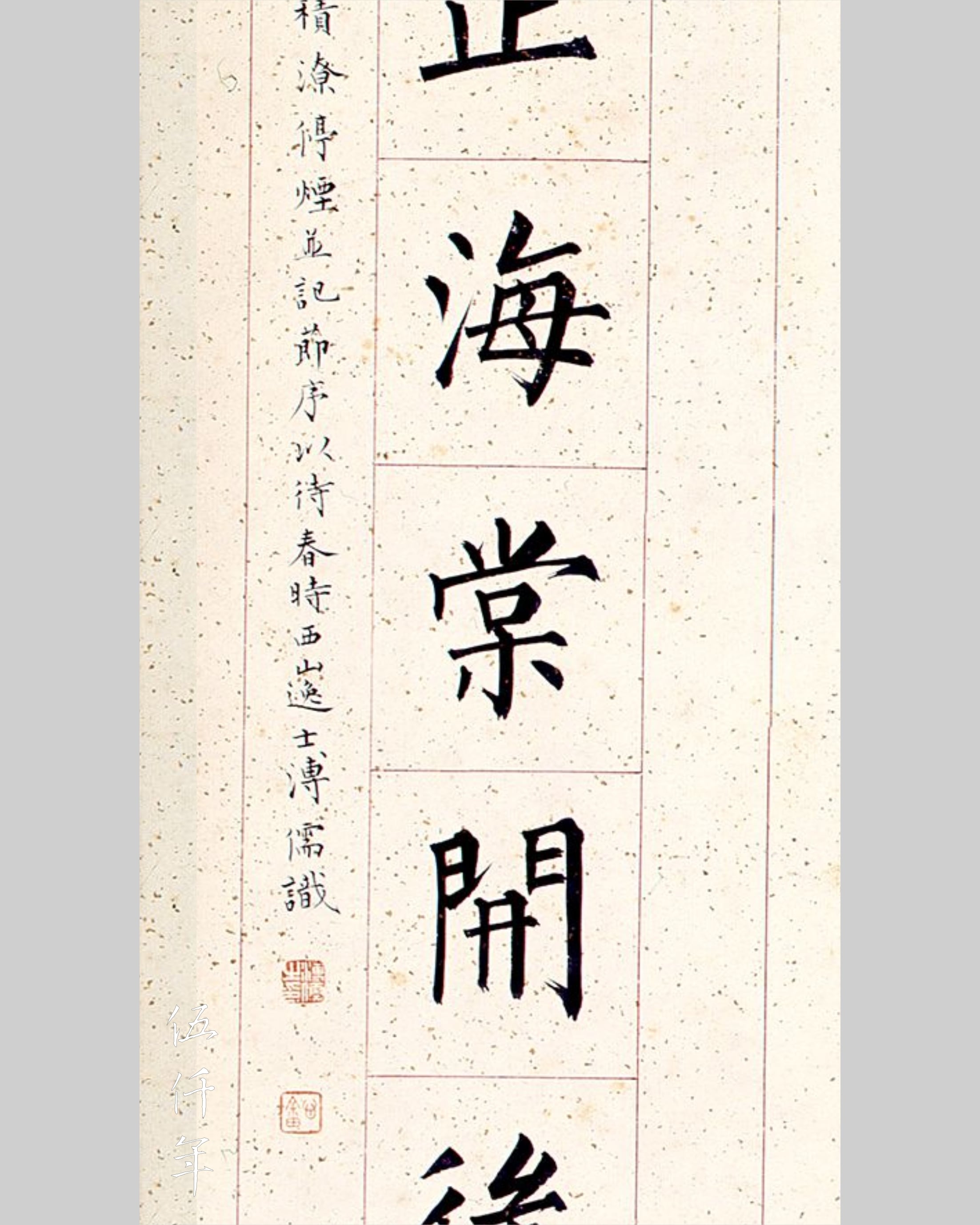

Front cover of A Brief Exposition of the Transmissions of the Thirteen Classics (十三經師承略解)

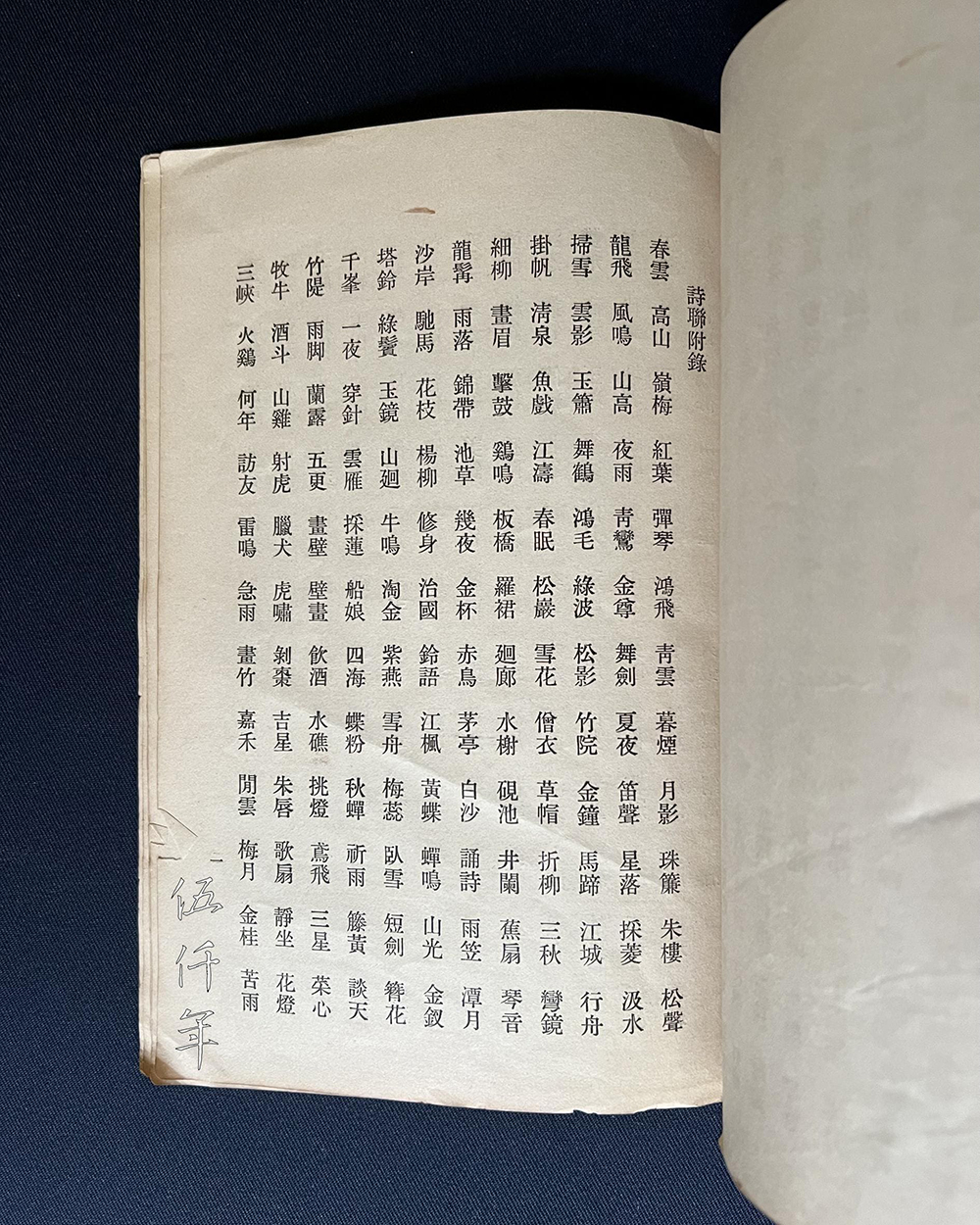

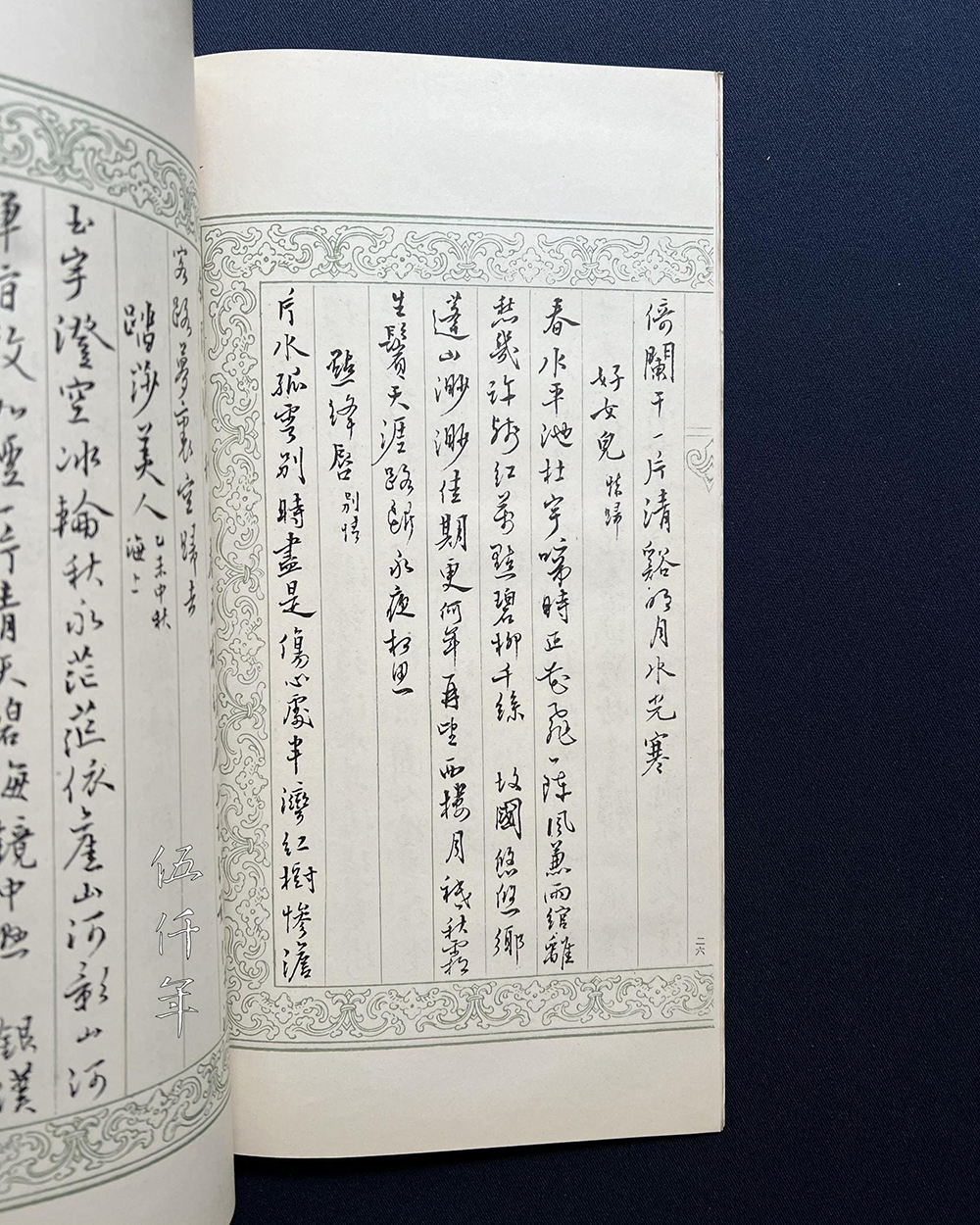

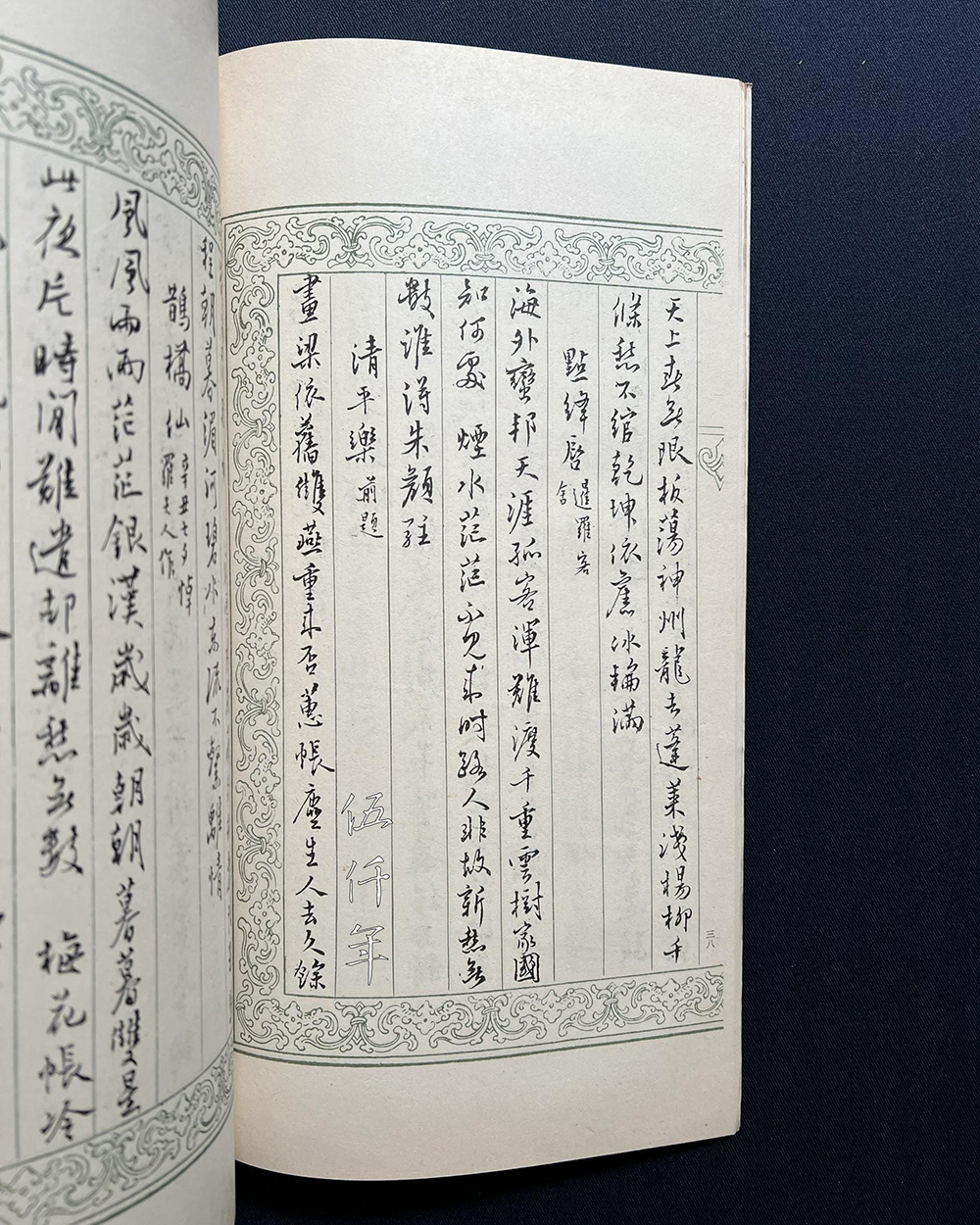

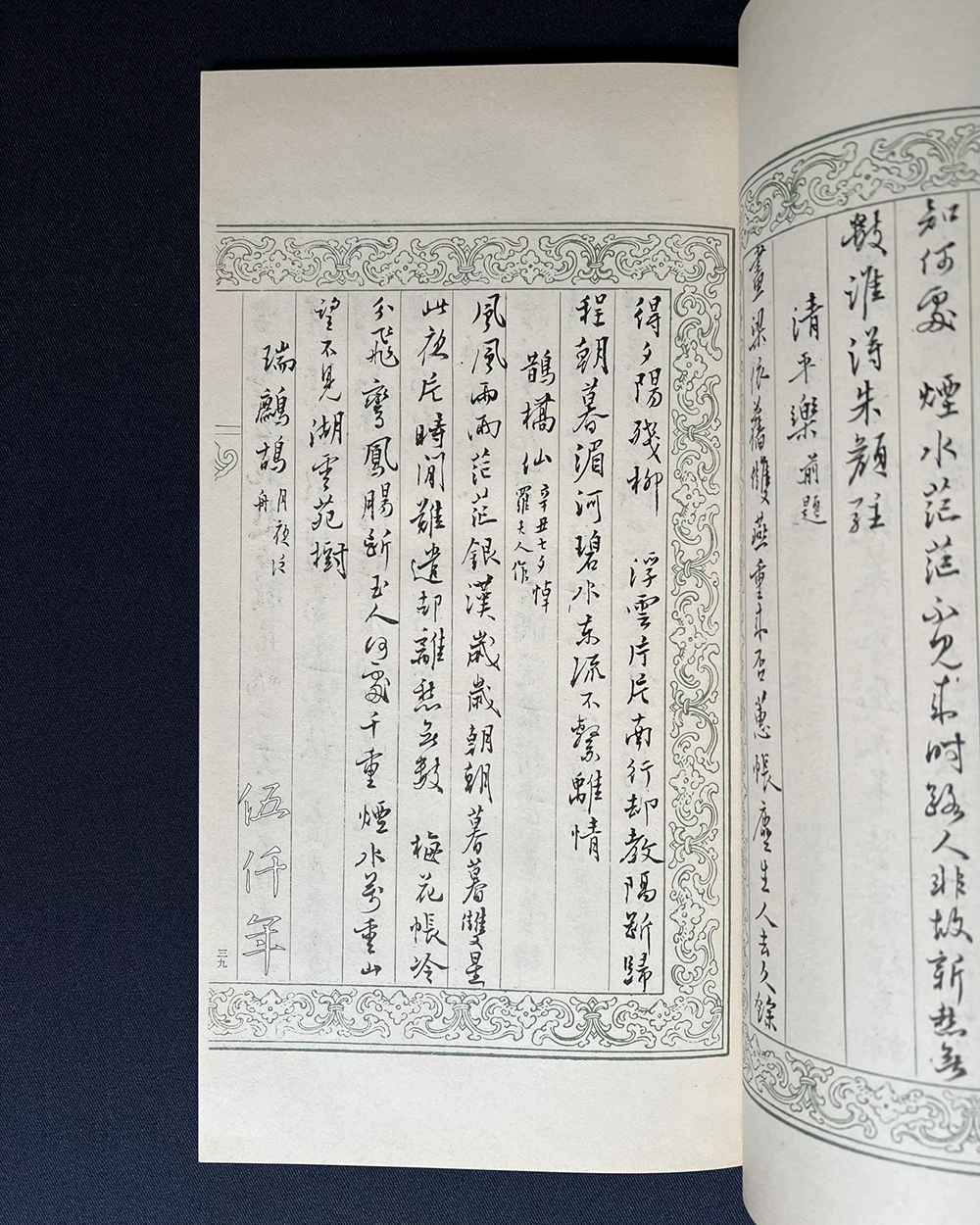

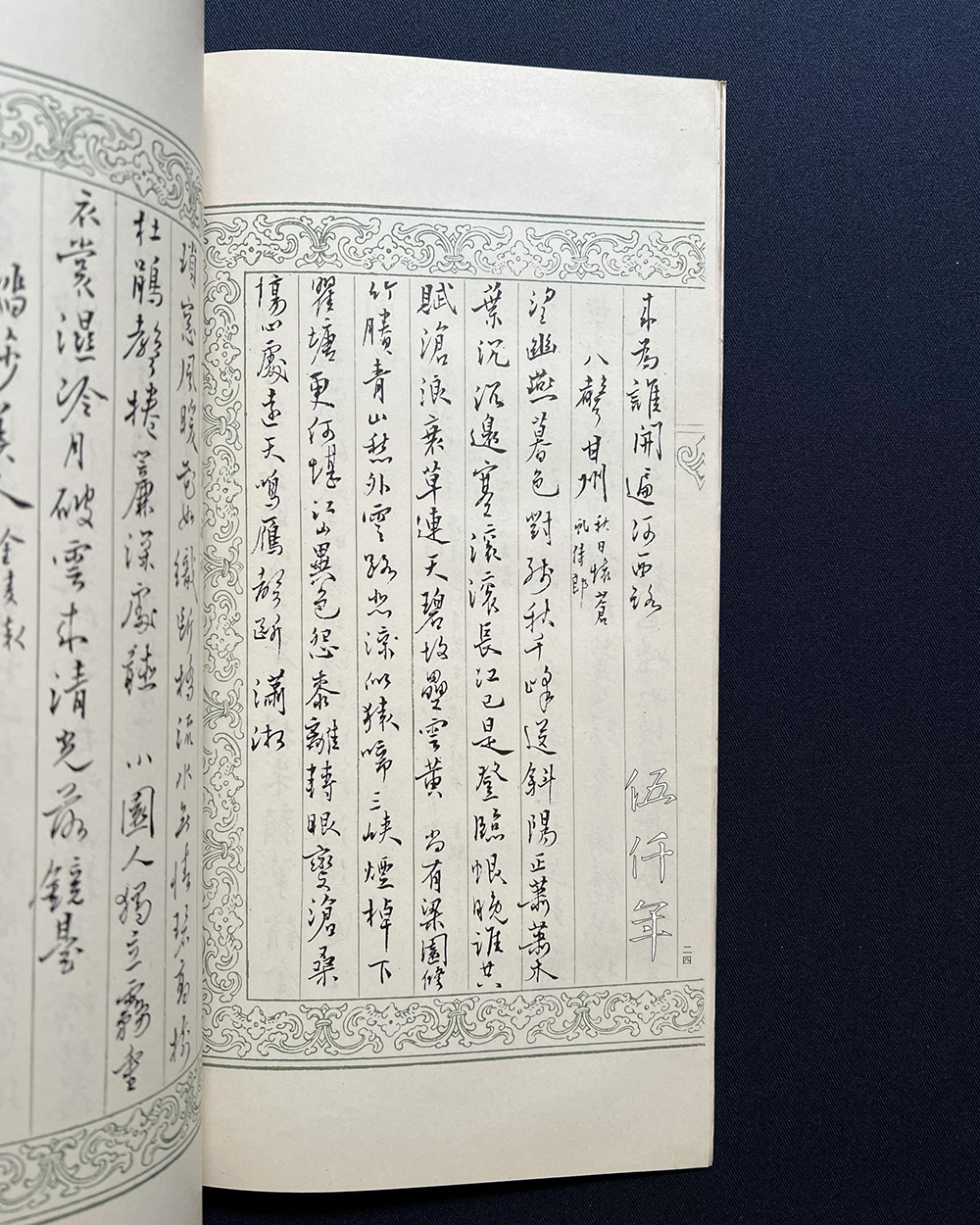

Inside page of A Brief Exposition of the Transmissions of the Thirteen Classics (十三經師承略解)

Inside page of A Brief Exposition of the Transmissions of the Thirteen Classics (十三經師承略解)

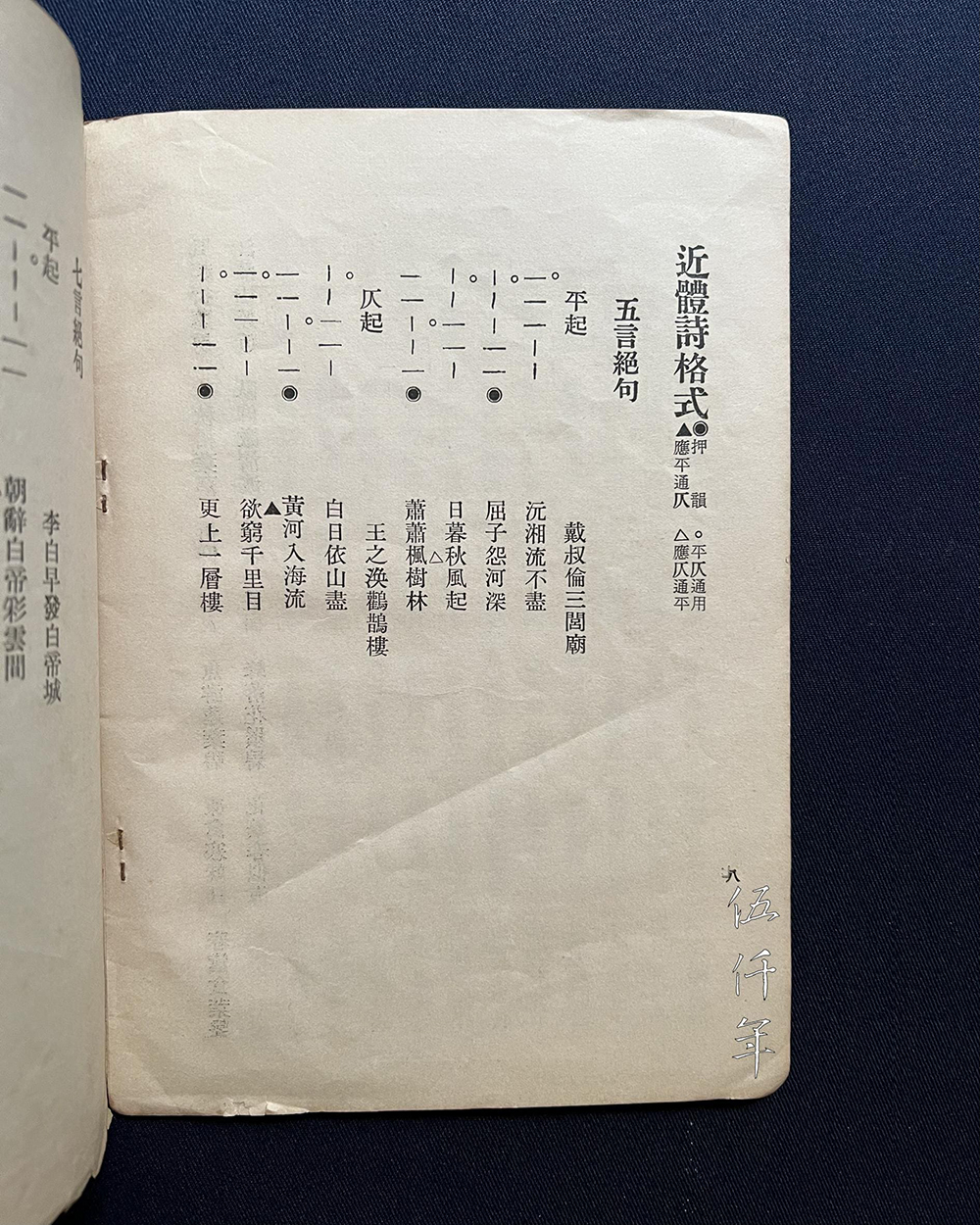

Inside page of A Brief Exposition of the Transmissions of the Thirteen Classics (十三經師承略解)

Inside page of A Brief Exposition of the Transmissions of the Thirteen Classics (十三經師承略解)

Back page of A Brief Exposition of the Transmissions of the Thirteen Classics (十三經師承略解)

Hence, according to his learning progression, one must first cultivate a righteous heart and a sincere mind, then one should acquire comprehensive knowledge of history and the Classics, along with the command of historical anecdotes, poetry and tz’u lyrics. Only in the final stage, will one venture into calligraphy and painting, with calligraphy clearly preceding painting. It is essential to build a foundation in calligraphy first, only then can there be success in painting. In modern times, there are many artists who can paint but cannot write calligraphy, let alone compose poetry or inscriptions. In Mr. P’u’s view, it would be difficult to reach a high level of excellence. Without studying and writing, how can it be possible to develop an expansive heart and mind, to reach refined sensibility? How can it be possible to avoid being common and vulgar when applying brush to paper? Chinese painting and calligraphy share the same principles; the better the calligraphy, the easier it is to advance in painting. When a painting is imbued with the spirit of calligraphy, only then can it be lofty and elegant.

In reality, although Mr. P’u taught tenaciously and patiently, from what I know, even among his disciples, I am afraid few if any adhere to his teachings. Some even went so far as to violate the rules of laying the groundwork for calligraphy, beginning not by copying ancient calligraphy carved on steles or written on scrolls, instead attempted rashly to directly emulate Mr. P’u’s branch-like distribution and breeze-like motion of brush strokes of his calligraphic style. This truly becomes a case of attempting to draw tigers but ending up with dogs!

It is easy to assume that deep respect for the teacher and assimilation of his teachings go hand in hand, but to be able to receive and reap various instructions still depend upon the karma of each student. As far as Mr. P’u was concerned, he never turned down a student because of age, gender, nor level of artistic skill. He treated all his students equally and taught each one with unflagging care. So whenever he visited Hong Kong, we would see his lodging fully packed with students. This spirit of teaching without disparity is truly admirable!

Portrait of Prince P’u Ju

People awed by his great fame in calligraphy and painting have regrettably overlooked his unyielding integrity, which was the most fundamental aspect of his life. His loyal affection, though notably directed towards the Manchu people, was also marked by his keen distinction of right and wrong, his apprehension of the intrinsic nature of propriety, these were the complete opposite to some people. When P’u I (溥儀) assumed the title of “Emperor of Manchukuo”, Mr. P’u tried his best to remonstrate against it, penning his counsel in the form of an article titled Ch’en-p’ien (臣篇 A Courtier’s Essay) to enunciate his view. Some lines in the article are:

“Never can an Emperor accede to the throne when the Nine Ancestral Temples are not properly erected, the country discontinues, ritual offerings not made to the proper spirits, and allegiance not sworn to the rightful reign .…. To seek the throne will be unwise, regret will be too late!”

He turned down requests and money for his artwork from the head of the Japanese Army. As a direct descendent of the Aisin Gioro clan, his ability to navigate his direction with such a precise compass in a time of consternation, uncertainty and confusion was testament to his extraordinary wisdom. Endowed with such outstanding acumen, it is certainly hard for an ordinary person to accomplish!

When the red tide of communism flooded and swept through China, remarkably Mr. P’u boarded a small boat from Chou-shan Islands (舟山群島), braved the tumultuous waves and sailed all the way to Taiwan. Mr. P’u was like an ascetic high above a mountain keeping his distance from the dusty world, a lonesome hermit acting to the dictates of moral rectitude. If he did not hold steadfast principles and a true understanding of the affairs in the world, how could he preserve his integrity and transcend the material universe?

Mr. P’u was an erudite scholar, yet sometimes his prejudices ran deep. The Republic of China had overthrown the three-hundred-year-old heritage of his ancestors, thus the words Republic of China often gave him an awkward feeling. During the time when he was traveling in Japan, he stayed at the residence of Mr. C. Y. Tung (董浩雲先生) in Tokyo. One day, he wrote a letter to his friend in the Chinese Embassy in Seoul, South Korea. On the envelope, he wrote the names of his friend and Seoul, Korea, leaving out “Embassy of the Republic of China in Korea”. He made special effort to ask one of the senior cooks in the kitchen to write these words for him, explaining: “This way, it will spare me from being melancholic”. Actions like this are naturally quite comical.

Portrait of Prince P’u Ju

It was in Tokyo when I first met him. I remember that day as I entered his room, he put down his paintbrush, rose from the tatami mat, clasped his hands over his chest, and greeted me with the words P’u Ju (溥儒) in utter earnestness and courtesy, introducing himself by name. The two words sounded so solemn and dignified, with a manner of such respect and sincerity that they left a deep impression on me. However, after conversing for half an hour, he began to use the phrase of pen-chao (本朝 meaning This Dynasty) over and over. I could not refrain from chuckling inside me at the phrase of pen-chao (本朝). By then, it was already forty something years into the Republic of China, he seemed to wish that I could join his reminisces of the four Ch’ing dynasty reigns of Tao-kuang, Hsien-feng, T’ung-chih and Kuang-hsü.

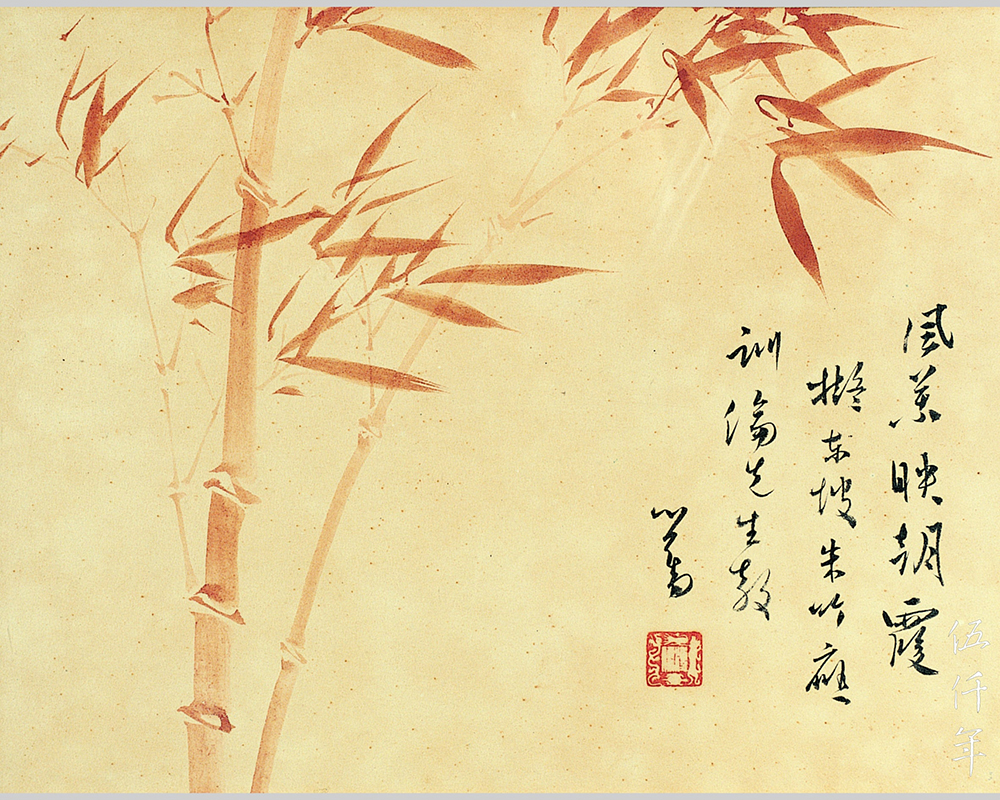

Vermilion Bamboo by Mr. P’u Ju gifted to Mr. Soong Hsün-leng for solving a Lantern Riddle

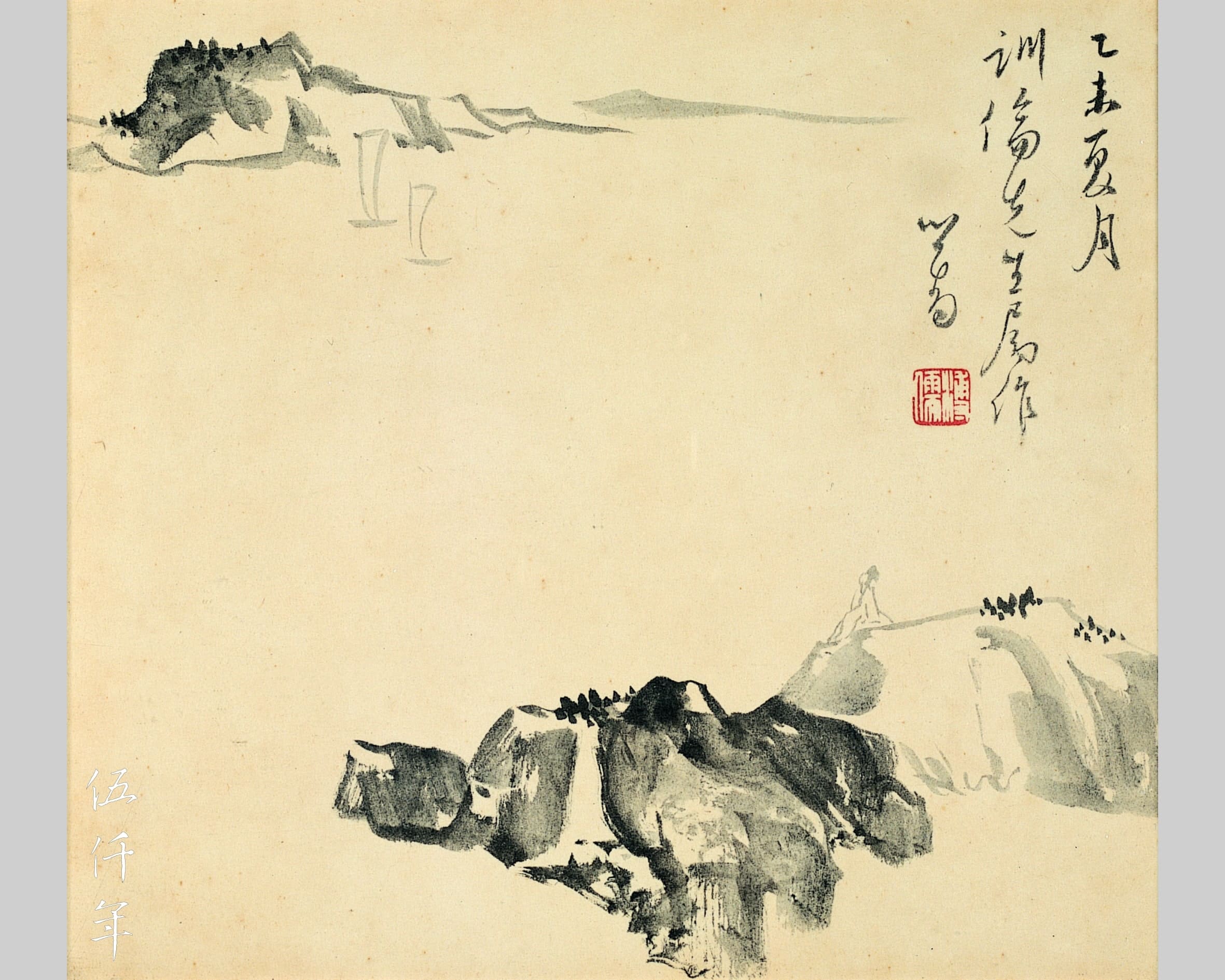

Lanscape by Mr. P’u Ju gifted to Mr. Soong Hsün-leng for solving a Lantern Riddle

In Tokyo, he spent his days composing poetry and writing calligraphy, he also made many lantern riddles for people to solve. Using the residual pieces of silk and paper from writing calligraphy, he painted impromptu pictures as prizes. One day, I solved a riddle from a line in The Works of Mencius Book 1, King Hwuy of Leang Part 1: “and on the south we have sustained disgrace at the hands of Ts’oo (南辱於楚)”. As a reward, he gave me a small painting of vermilion bamboo with the inscription “Imitating the brushwork of Su Tung-p’o (擬東坡筆意)”. In addition he also gifted me a simple landscape painting that was tranquil, expansive and carefree, a true masterpiece.

Mr. P’u Ju wrote the horizontal calligraphy plaque for Island Club, Hong Kong, property of Mr. C. Y. Tung

Vista of Island Cub, Hong Kong

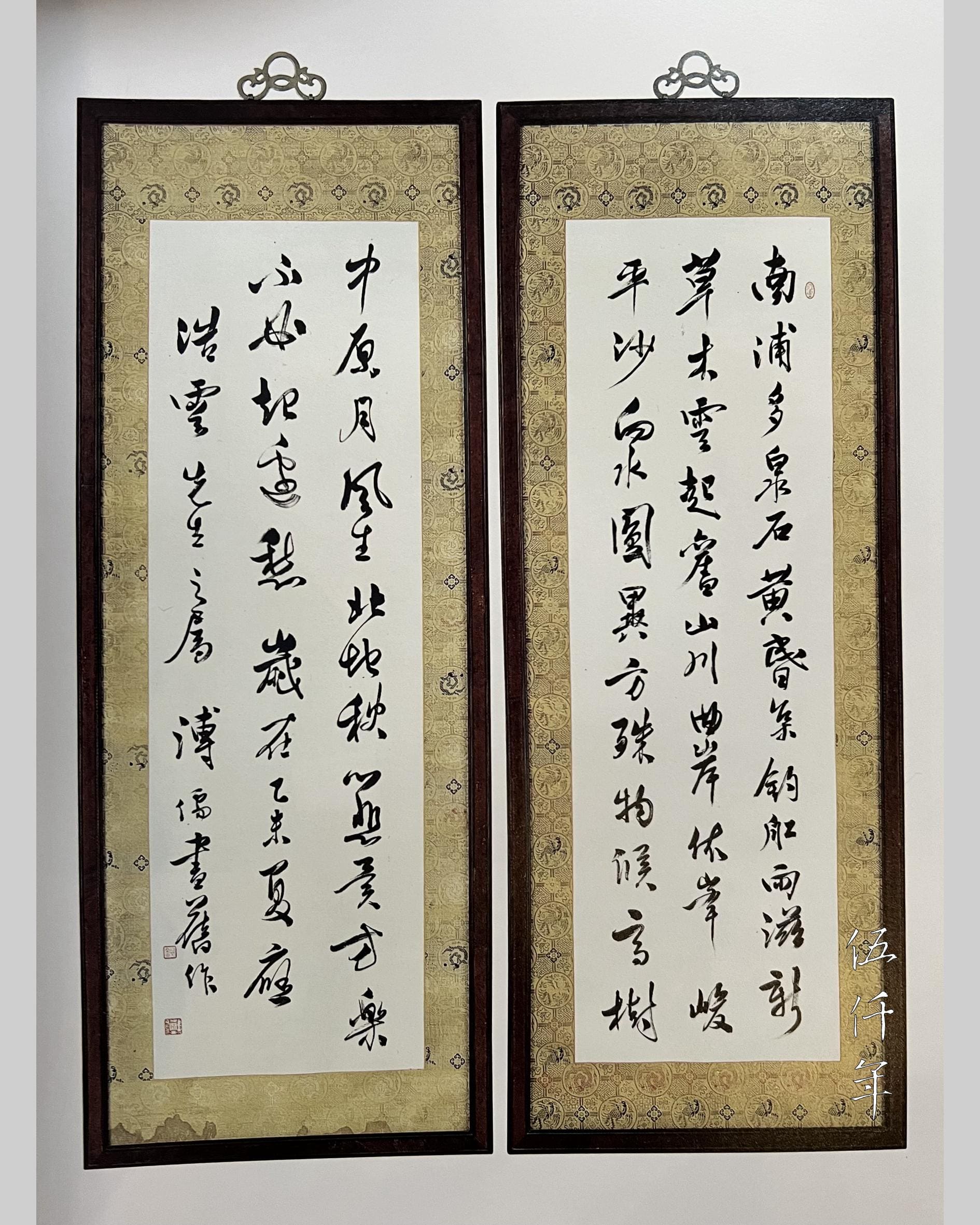

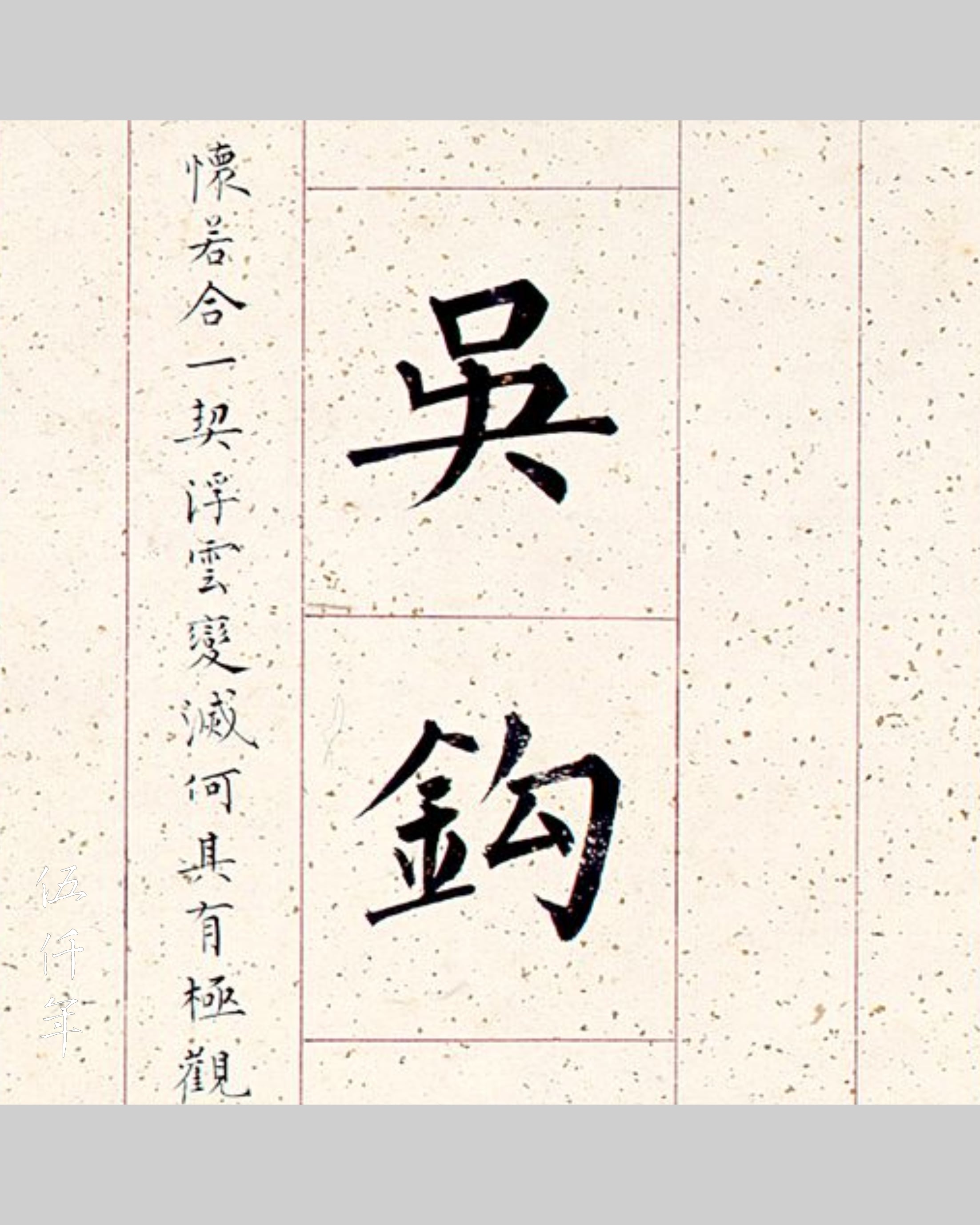

Two scrolls out of a set of six calligraphy scrolls by Mr. P’u Ju dedicated to Mr. C. Y. Tung

Amongst his calligraphic works, the piece I admire most is a set of six vertical hanging scrolls presented as a gift to Mr. C. Y. Tung. The poems on the scrolls consist of sentences with five characters each, written in cursive script (草書) and executed with full concentration and attentiveness. The poems were composed by him earlier on. The calligraphic movement is like dancing phoenix that frightens snakes, like fluttering wild goose that startles animals. Although his brush strokes are soft and smooth, they are nevertheless overpowering, subtle and natural. He had truly reached a state of fluidity for both heart and hand, and his brush never moved in vain. For all the cursive scripts by Mr. P’u I have seen in my life, this set of six vertical hanging scrolls rank as the finest. They now hang at the Island Club (香島小築) in Deep Water Bay. I once told Mr. P’u in person that this set of calligraphy scrolls were the most skillful work I had seen from him. He smiled casually and replied: “After disturbing the host for so long, how can I not express a bit of gratitude?”. It is discernible that he was very satisfied with this work too.

Indeed the words “full concentration (聚精會神)” in my opinion, are the basic requirement of calligraphy for any artist, whether a master or a novice. At Mr. P’u’s level of artistic proficiency, when full concentration was applied, manifested from absolute genuineness, exerted for sure with his full capability, and emanated from heart to hand, how could it not become a masterpiece of almost supernatural artistry?

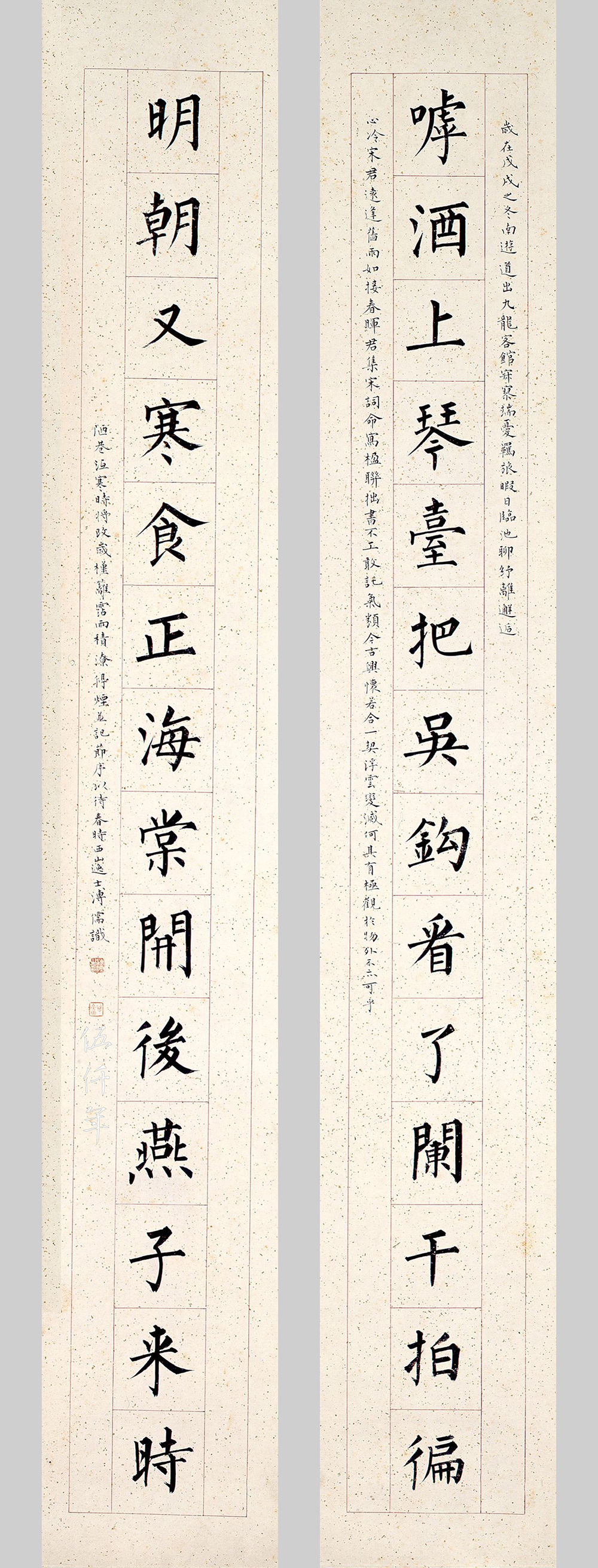

A pair of calligraphy couplets in regular script by Mr. P’u Ju dedicated to Mr. Soong Hsün- leng

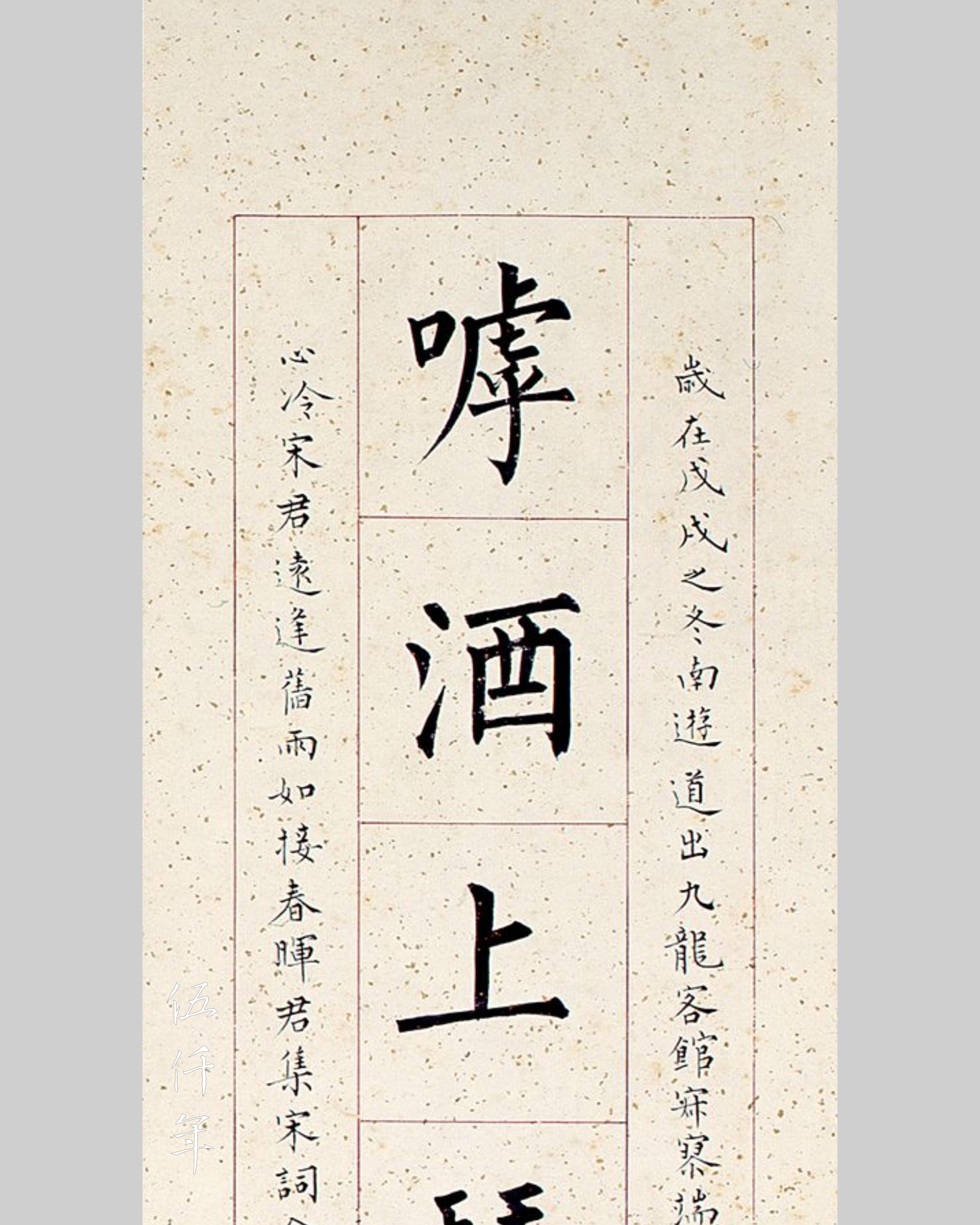

Detail of the first calligraphy couplet in regular script by Mr. P’u Ju dedicated to Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

Detail of the second calligraphy couplet in regular script by Mr. P’u Ju dedicated to Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

Detail of the second calligraphy couplet in regular script by Mr. P’u Ju dedicated to Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

His calligraphic style of regular script (楷書) closely resembles that of Yung-hsing (永瑆 1752-1823), also known as Prince Ch’eng (成親王) , but is even more elegant. In truth he benefitted from the works of Chu Sui-liang (褚遂良 596-658). At one time I asked him to write a pair of calligraphy couplets that consisted of selected lines from Sung dynasty tz’u lyrics put together by Liang Ch’i-ch’ao (梁啟超 1873-1929). The regular script characters were to be written in two-inch vermillion-lined square spaces drawn on gold-flecked paper. It turned out to be exceptionally exquisite and elegant. The words of the pair of calligraphy couplets read:

Come wine for the zither table, after gazing at the scimitar sword, thump hard the railing in rage.

Han-shih Festival here tomorrow again, begonias have just bloomed, and swallows now to come.

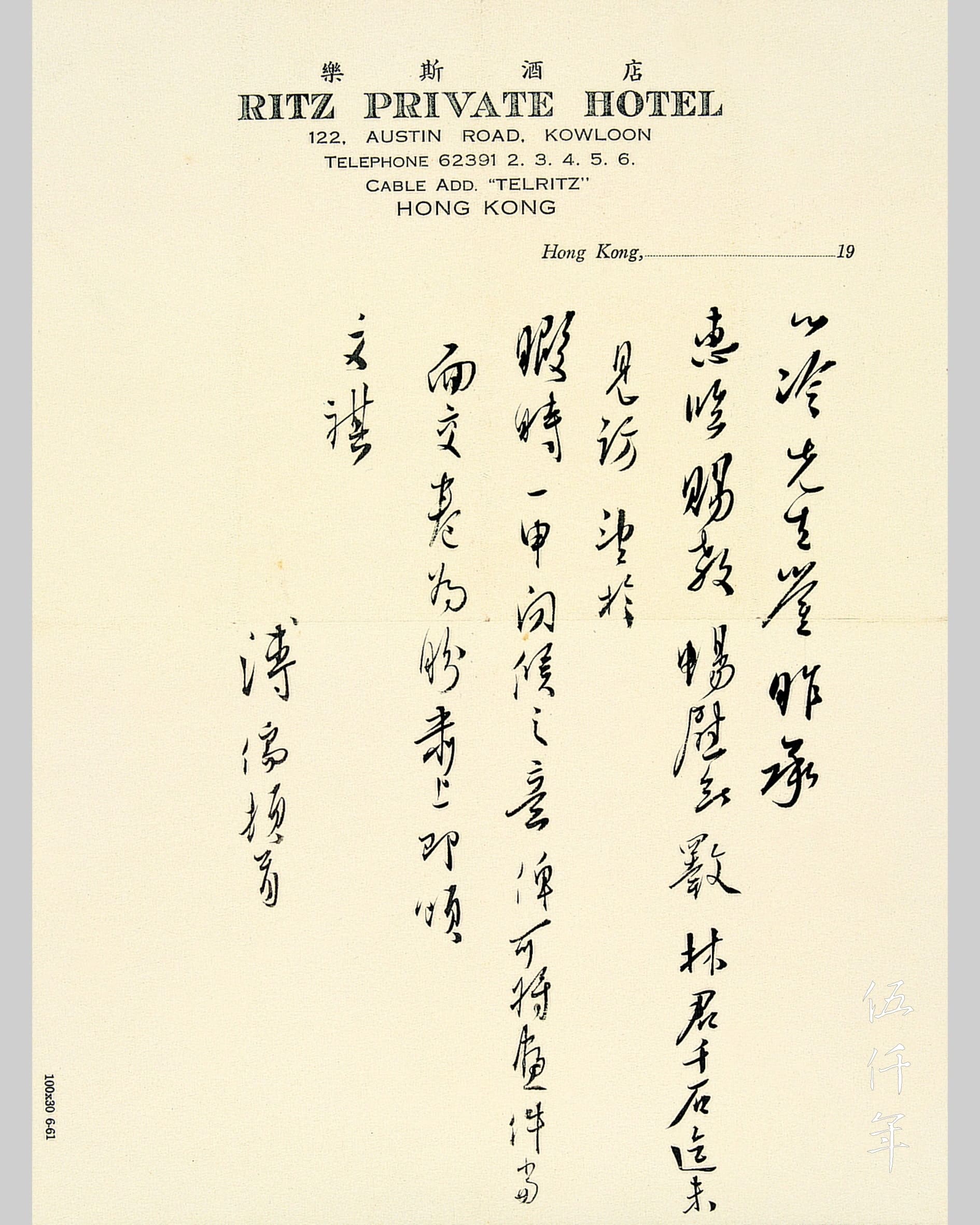

Mr. P’u specially added a lengthy colophon in small regular script. It reads:

“In the winter of wu-hsü year (1958), I travelled south, arriving in Kowloon. My lodging is quiet and lonesome. I am a traveller full of worries, and in my spare time, I write calligraphy to relieve my solitude. I ran into Mr. Soong Hsün-leng (hao Hsin-leng) unexpectedly. Encountering an old friend in a distant place is like receiving sunshine in spring. He requested me to write a pair of calligraphy couplets with lines he put together from Sung dynasty tz’u lyrics. I am not proficient in calligraphy, so I am not brave enough to profess that I am his kindred spirit. The lamentations of the ancients and that of ourselves are indeed identical. The mutations and destructions seen in floating clouds, when will they come to an end? Is it possible to contemplate existence with detachment? This shabby lane, this frosty cold, this year that will end shortly. Rain soaks the hibiscus hedge, water gathered dissipates the smoke. I mark the season and await the arrival of spring.

Composed by the Recluse of the Western Hills, P’u Ju (西山逸士溥儒)”

A short composition of such outstanding structure, concise and elegant as it is, completely embodies the spirit of the prose of the Six Dynasties. The purport entrusted in this piece is profound, the meaning extends far beyond the actual words, making it ever more tantalizing! His calligraphy in regular script has been critiqued in the past as “the foremost in five hundred years”. Looking at this pair of calligraphy couplets, one can discern the scope of elegance and orderliness in its manner and spirit, and realizes that such commentary is surely not empty words.

He had many insights that were deeper than ordinary people. On one occasion, I asked his opinion regarding the calligraphy of a certain prominent figure. He responded with great seriousness:

“When the ancients wrote calligraphy, the words had flesh and bone. If there is flesh without bone, it is almost vulgar; if there is bone without flesh, it is almost withered. Therefore, the calligraphy and writings during an era of peace and prosperity are graceful and refined. However, in times of decline and turmoil, marked by extremes of hunger and barbarism, there emerges a style of calligraphy and painting that is barren and ferocious. This too is the result of fate!”

He also told me that someone once asked him, “How does your painting compare to those of your contemporaries?” He replied with sixteen Chinese words: "In the presence of the ancients, I dare not relinquish self-motivation, in the presence of my contemporaries, I dare not be immodest. (吾於古人,不敢不勉,吾於今人,不敢不讓)"

He hurried to Hong Kong several times just to feast on Chinese hairy crabs. He stayed once at the Kowloon Shamrock Hotel (九龍新樂酒店) and twice at the Kowloon Ritz Hotel (九龍樂斯酒店). As a matter of fact, his way of eating Chinese hairy crabs was really messy, it could be said that he was only devouring and not savouring. I noticed every time he could eat more than ten crabs, in fact if the shell fragments he spat out were to be examined, the crab meat of at least six to eight crabs could be retrieved.

Letter from Mr. P’u Ju to Mr. Soong Hsün-leng with the letter heading of Kowloon Ritz Hotel

Rather every time he visited Hong Kong, it was an opportunity for many of his friends in the city to be drawn closer to him and sought his counsel. He delivered academic lectures at both the University of Hong Kong and the New Asia College one after the other, injecting a burst of vitality into the academic and artistic communities in Hong Kong. As far as I know, there are two learned and all-rounded scholars in Hong Kong whom he admired and felt a deep connection. One is Professor Jao Tsung-I (饒宗頤) at the University of Hong Kong, and the other is Mr. Lin Ch’ien-shih (林千石) who excels in all three branches of poetry, calligraphy, and painting. Tsung-I immerses himself in thousands of volumes of rare books and is well read on many topics. He is an internationally acclaimed Sinologist. As for calligraphy, painting and writing, they are just his leisurely activities. The calligraphy of Ch’ien-shih follows the lineage of Wang Hsi-chih (王羲之 303-361) and Wang Hsien-chih (王獻之 344-386), his painting is inspired by Tung Yüan (董源 934-962). He once dedicated to me a small hand scroll measuring over ten feet long in running cursive script of classical poems he himself composed, which bore a striking resemblance to the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Lan-ting Gathering by Wang Hsi-chih, and the calligraphy is as dazzling and graceful as the vista of ascending a jade mountain. In addition, he is an expert seal engraver, truly a multi-talented and versatile artist. Both Jao and Lin have a lofty and serene temperament, it is only because of their resistance to be part of the worldly currents that they reciprocate well with the habit of Mr. P’u.

Mr. P’u knew that I enjoyed reading tz’u lyrics. He often casually picked up some scraps of paper from the table and wrote down those tz’u lyrics that he was particularly proud of for me to read. Although they were spontaneously copied, and their calligraphic merit did not quite matter, yet he would still place his signature, impress his seal, and add a salutation. From this we can discern the prudence and attentiveness exercised by an elder.

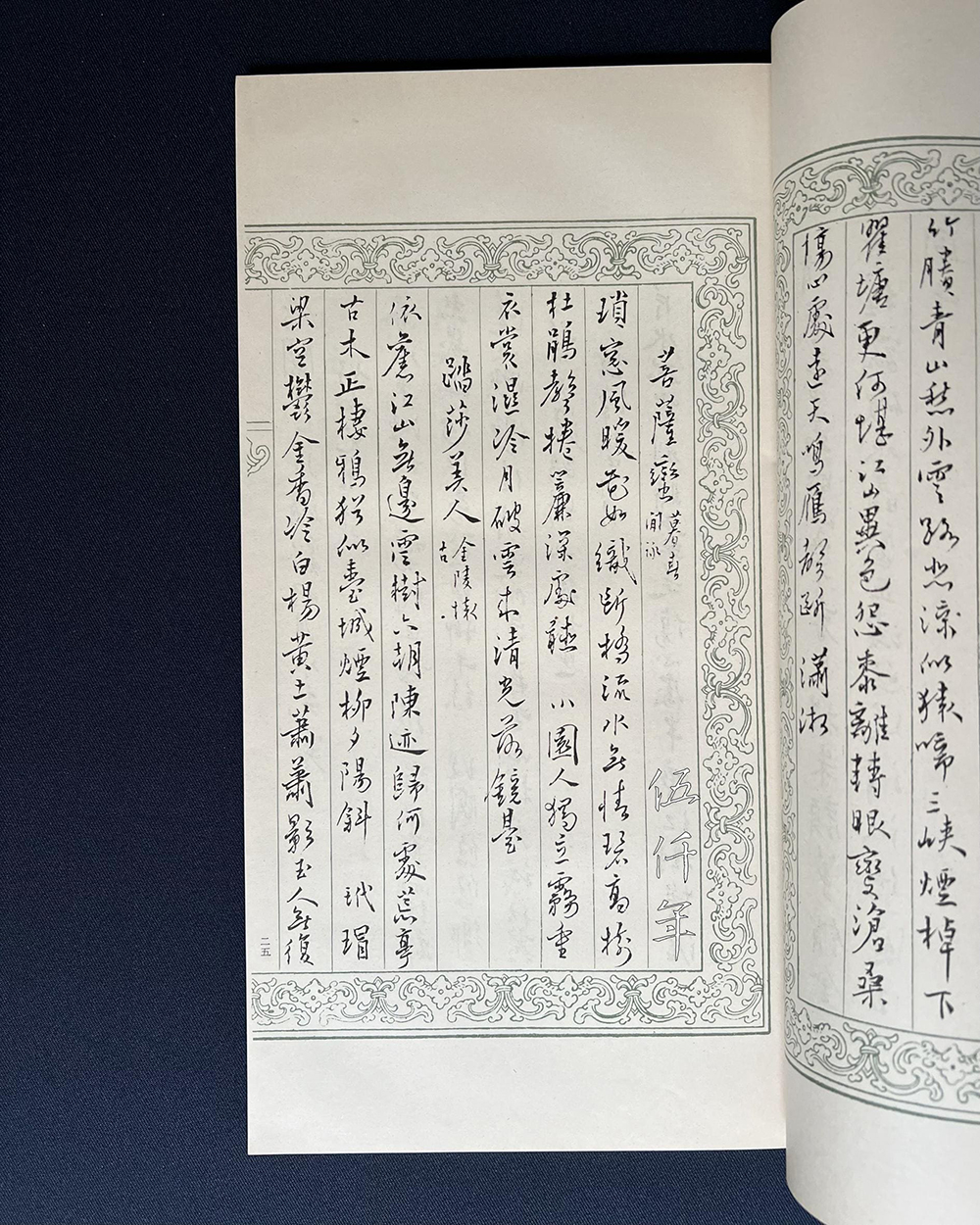

First page of handwritten tz’u lyric To the tune T’a sha mei-jen (踏莎美人) by Mr. P’u Ju published in The Poems, Tz’u and Couplets of Han-yü T’ang

Second page of handwritten tz’u lyric To the tune T’a sha mei-jen (踏莎美人) by Mr. P’u Ju published in The Poems, Tz’u and Couplets of Han-yü T’ang

His tz’u lyrics are as intricate and seductive as those of Chang Hsien (張先 990-1078), with an exceptional level of artistic conception. An example is Nostalgia for Chin-ling (Nanking), To the tune T’a sha mei-jen (踏莎美人). It reads:

Rivers and mountains

Just the same.

Trees and clouds

No edge in sight.

The ruins of Six Dynasties

Who knows where it is?

A desolate pavilion,

Crows nesting

On ancient trunk.

Like a city in spring,

Willow in mist,

Sun setting south.

Swallows have left

The painted beams,

Tulips feel the cold.

Aspen trees and yellow soil,

Lone lone shadow.

Once upon a time,

A figure reclined

Against the balustrade.

Surface of clear stream,

Luminous moon,

Cold vivid reflection.

First page of handwritten tz’u lyric To the tune Ch’ing p’ing le (清平樂) by Mr. P’u Ju published in The Poems, Tz’u and Couplets of Han-yü T’ang

Second page of handwritten tz’u lyric To the tune Ch’ing p’ing le (清平樂) by Mr. P’u Ju published in The Poems, Tz’u and Couplets of Han-yü T’ang

Another example is Remembering the Old Abode, To the tune Ch’ing p’ing le (清平樂). It reads:

Painted beams

Of olden days,

Have the two swallows

Made it back?

Behind the curtain,

A vanished world

Forsaken long ago.

What is left,

Dusk and wilted willow.

Puffs of cloud,

Each traveling south.

Yet homeward journey,

Stopped and blocked.

Day and night,

Clear water of River Mae

Keeps flowing east,

Carrying not even

The grief of separation.

Handwritten tz’u lyric To the tune Pa sheng Kan-chou (八聲甘州) by Mr. P’u Ju published in The Poems, Tz’u and Couplets of Han-yü T’ang

An example of a long tz’u lyric is To the tune Pa sheng Kan-chou (八聲甘州). It reads:

Gazing towards the north,

Colours of dusk,

Accost the waning Autumn.

Endless peaks,

Farewell sunset.

This season of

Desolate trees

Fallen leaves,

Heavy and gloomy border,

Rolling waves from Yangtze River.

Regret it is too late,

To climb to the summit.

Who will join me writing

An unworldly song?

Fields of shrivelled grass

Touch the distant blue sky.

The former hill dwelling

Capped by imperial clouds.

Still there is Liang Garden

A refuge for the soul.

This sorrow beyond

The last green hills,

Cloud covered treks,

Sad and cold.

Like listening to gibbons

Of Three Gorges,

Wading an oar

Across the misty river

To Chü-t’ang.

How can one bear

The change of flag

For our country.

I resent the ancient tale in Shu-li,

In a blink of an eye,

Our story too.

Heartache moment,

Wild geese shrieking from afar,

Parting the Hsiao-hsiang River.

These poems are mournful and arousing, interrupted by lamentations, expressing deep melancholy and frustrations. He wrote:

“How can one bear

The change of flag

For our country.

I resent the ancient tale in Shu-li,

In a blink of an eye,

Our story too.”

The anguish and pain experienced by this “former imperial prince” in those days suddenly fell on ourselves today too. However, at that time, he could still live in the land he used to live, breathe the air of freedom as before, while for us today, we are deprived of even the most basic right to return to our native land.

Themes of “sorrowful life” often appear in his writings, such as when he first came to Hong Kong, one autumn night he boarded a boat for pleasure and composed a tz’u lyric To the tune Che-ku t’ien (鷓鴣天). It reads:

Snowdrops falling on rushes have startled the white gulls,

And the clear waters mirror a dappled sail.

The perfumed grass is blue, limitless, immense;

A wanderer is stranded south of the river

And autumn prevails everywhere.

There are only

The moon in the sky

The house on the bank,

A light cloud, some cool dews,

And curtain hooks.

In the misty void no sign of my country dear—-

But should it appear, how much sadder indeed!

(Translated by Mr. T. C. Lai, a friend of Mr. Soong Hsün-leng)

The last two lines indeed speak of something directly comprehensible, but also suggest a more profound interpretation. They contain so much lamentable reflections. Moreover, this tz’u lyric is faraway in spirit and ethereally beautiful as if a painting is incorporated within the tz’u lyric. I had a sudden idea and at once begged Mr. P’u to paint this tz’u lyric into a picture, turning it into a true masterpiece under heaven. Mr. P’u agreed and said that he would slowly complete it after his arrival in Taiwan. For this kind of dedicated and meticulous work, it had to be crafted in the manner earlier described in this essay “full concentration”. It was not something that could be hastily executed under the window of a hotel room or amidst the hustle and bustle of a crowd of guests.

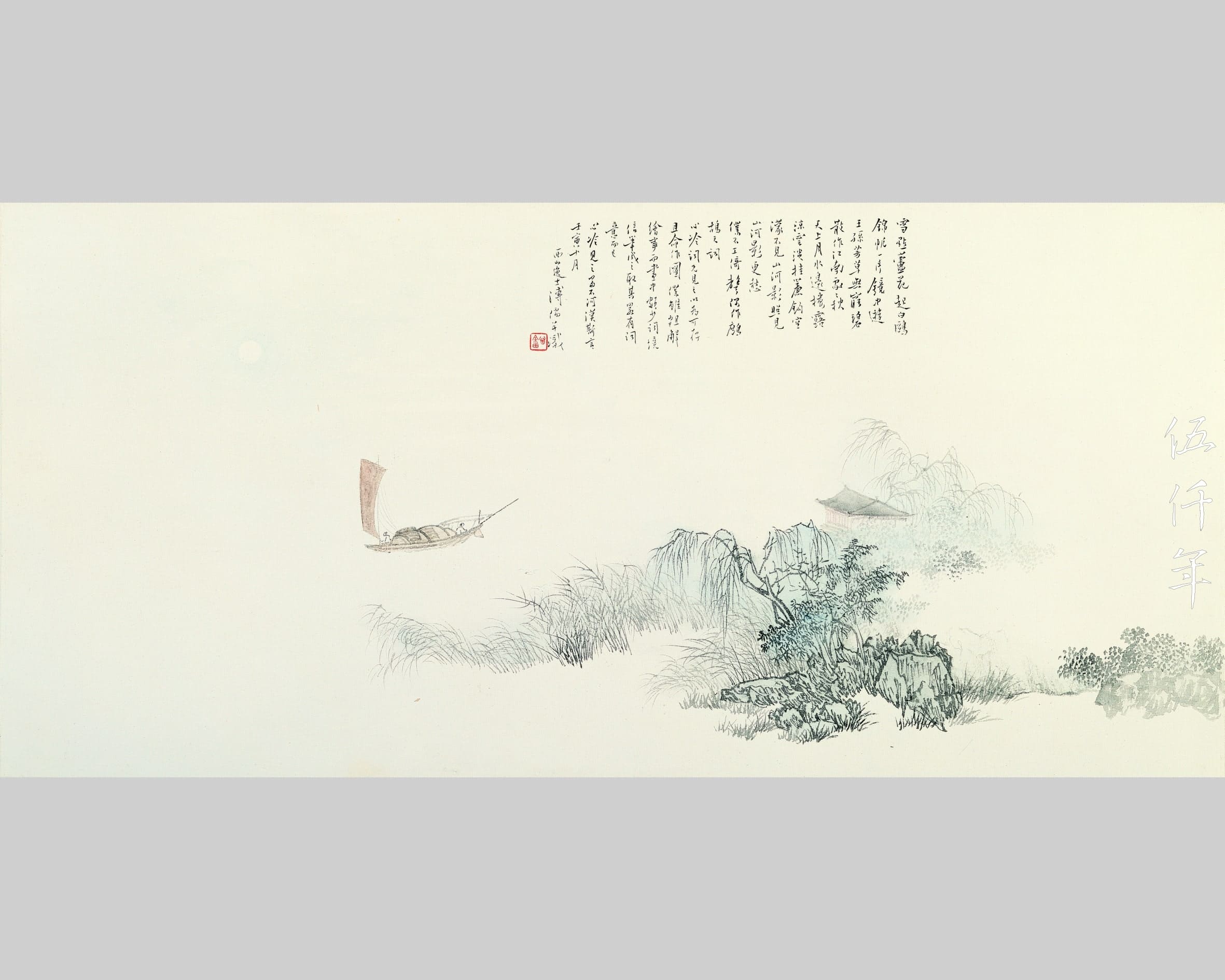

Painting of the tz’u lyric To the tune Che-ku t’ien (鷓鴣天) by Mr. P’u Ju dedicated to Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

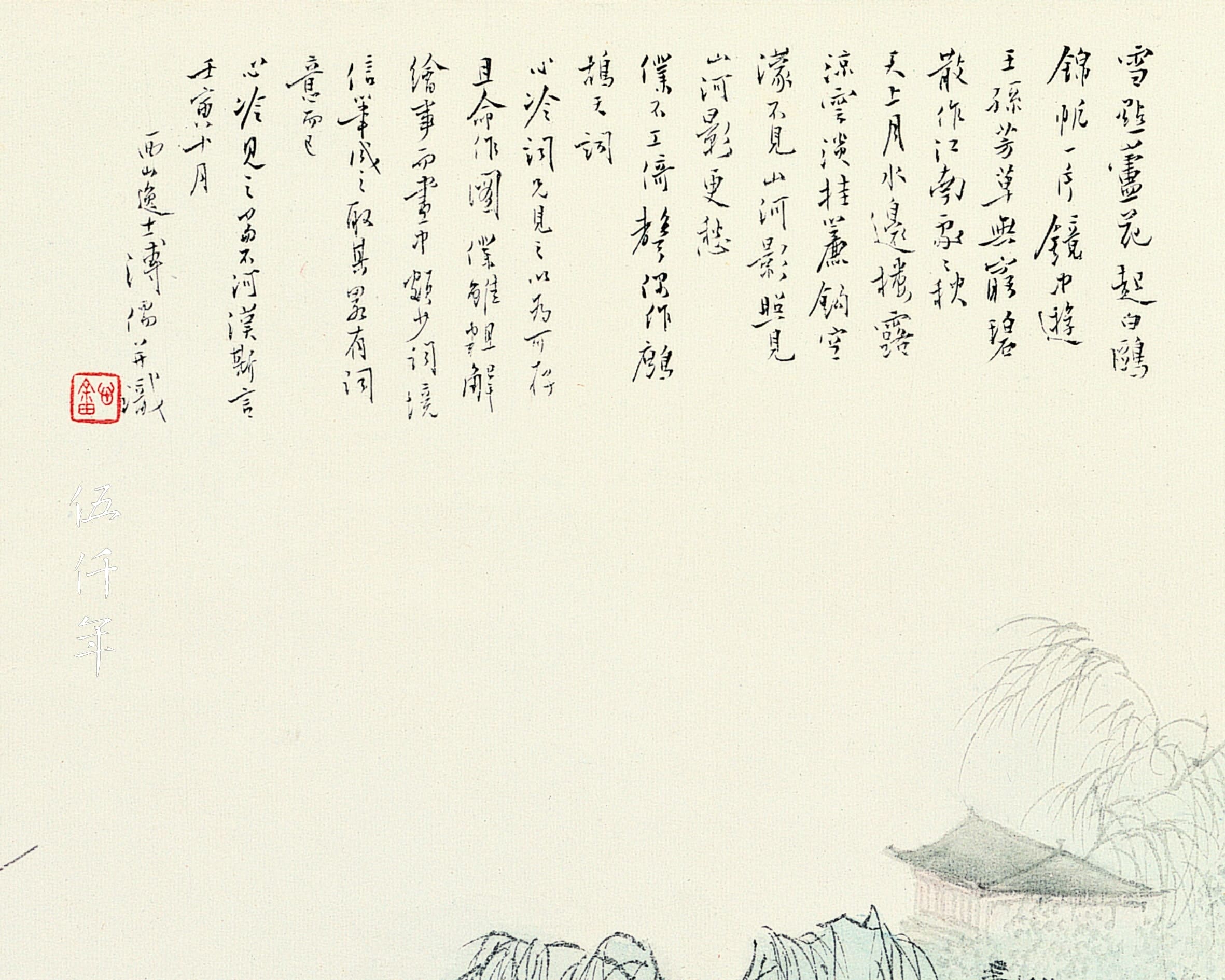

Inscription on the painting To the tune Che-ku t’ien (鷓鴣天) by Mr. P’u Ju dedicated to Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

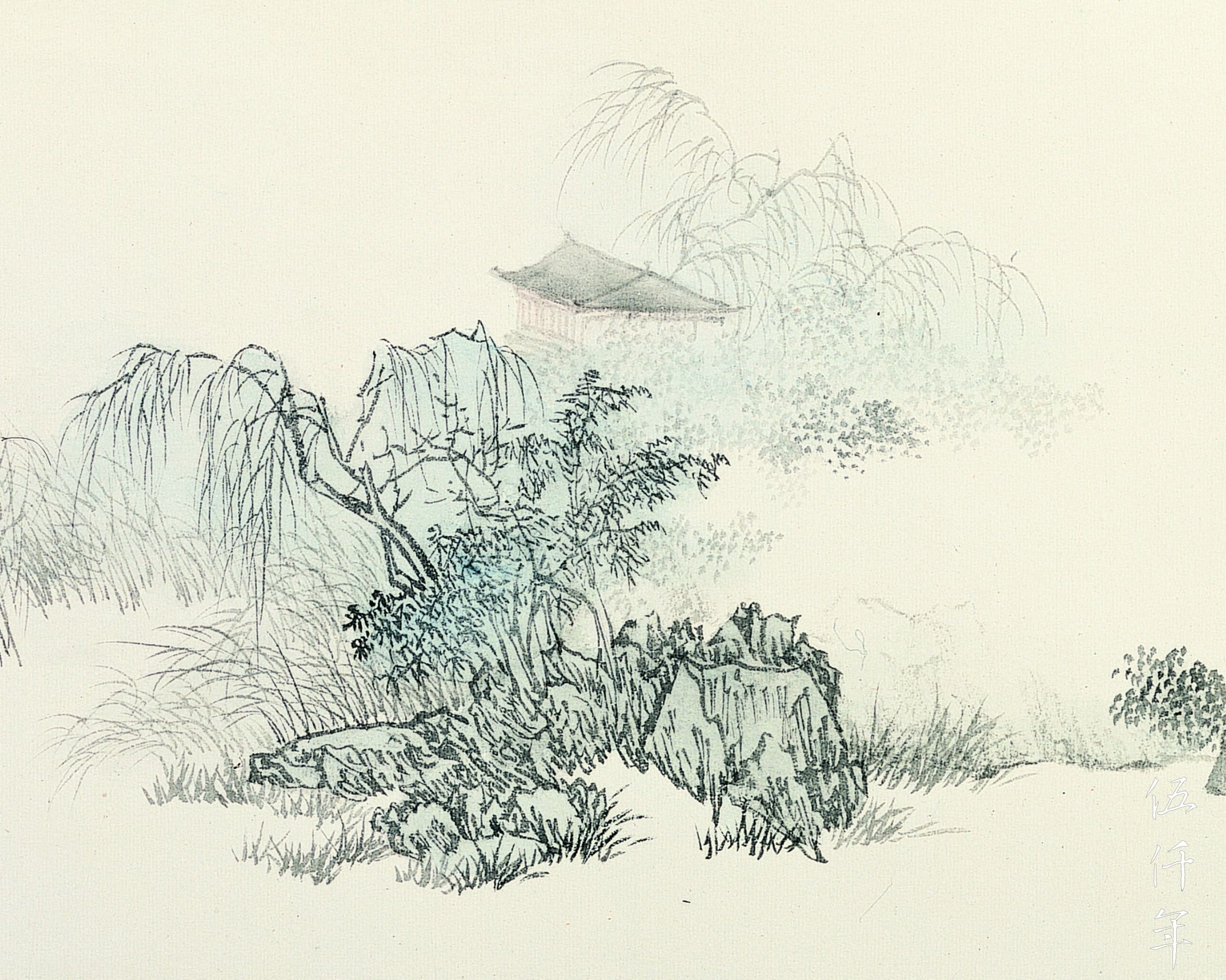

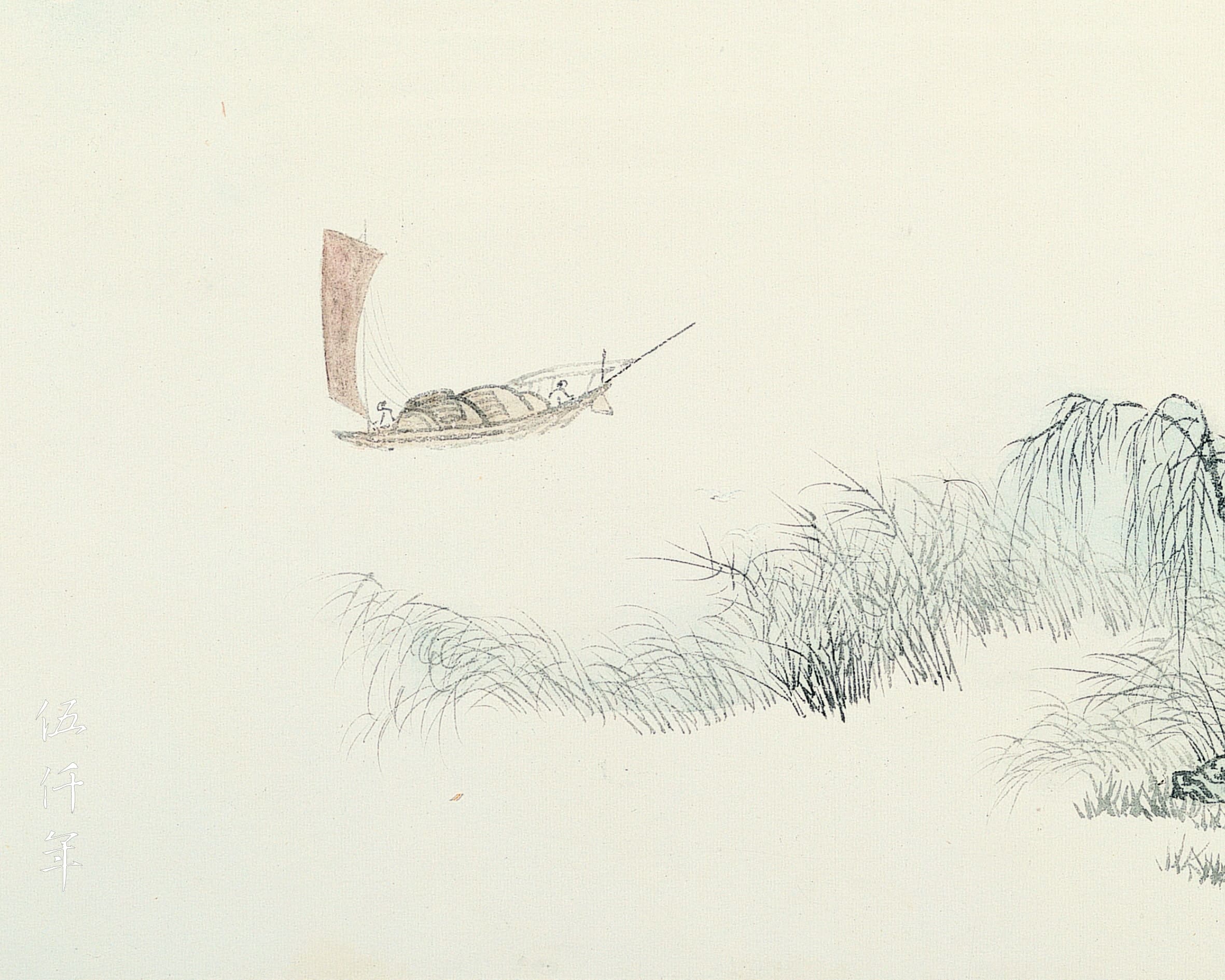

Detail of the painting To the tune Che-ku t’ien (鷓鴣天) by Mr. P’u Ju dedicated to Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

Detail of the painting To the tune Che-ku t’ien (鷓鴣天) by Mr. P’u Ju dedicated to Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

Sure enough, when he returned to Hong Kong the following year in autumn, he gave me the painting in person. Such was my astonishment and delight as I held and looked at it! A sense of spaciousness and subdued charm filled the entire scene, overwhelming the viewer. The pale reds and light greens were serene and elegant to their utmost, while the artistic conception and composition were transcendentally pure and unworldly. With this kind of brushwork, even Wen Cheng-ming (文徵明 1470-1559) and T’ang Yin (唐寅 1470-1524) would be humbled if they were resurrected, let alone all the other contemporary artists. In addition to inscribing the tz’u lyric To the tune Che-ku t’ien as aforementioned, he also added a colophon, the words are as follow:

“I am not skilled in tz’u lyric. By chance I composed To the tune Che-ku t’ien. When my tz’u brother Hsin-leng (心冷) saw it, he deemed it worthy of preservation and bid me to create a painting. Although I understand the rudiments of painting, it has very little aura of tz’u lyric. It is done impetuously, and only manages to convey a fraction of the aura of tz’u lyric. When Hsin-leng sees this, I hope he will not think this superficial and hollow. Written in the tenth month of jen-yin year (1962) by the Recluse of the Western Hills, P’u Ju.”

That evening, at a dinner gathering of Hong Kong’s literati and artists in honour of Mr. P’u at the North China Restaurant (豐澤園), I clutched this painting. Many friends at the banquet admired the painting endlessly, and unanimously agreed that it was indeed an exquisite masterpiece by Mr. P’u in recent years.

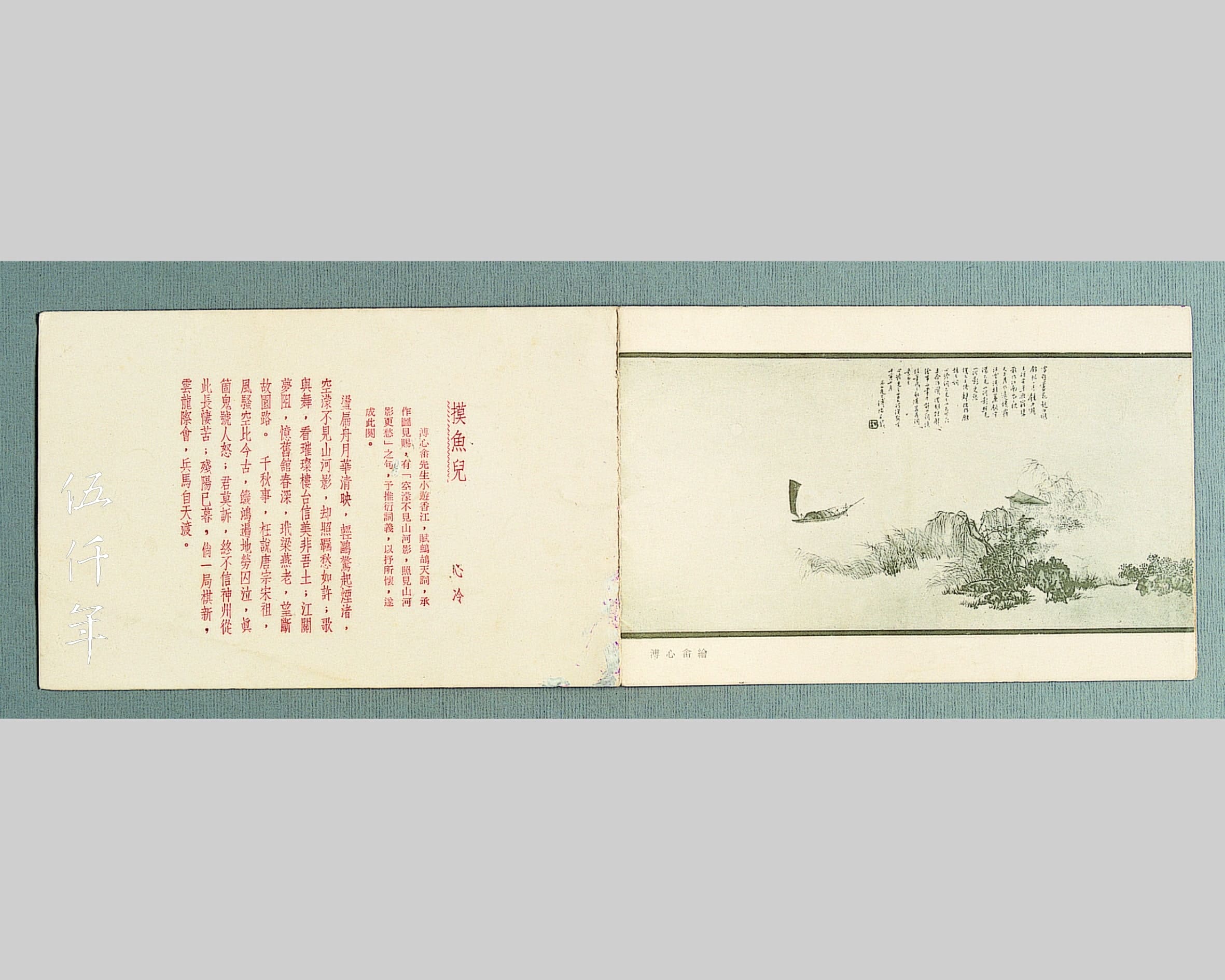

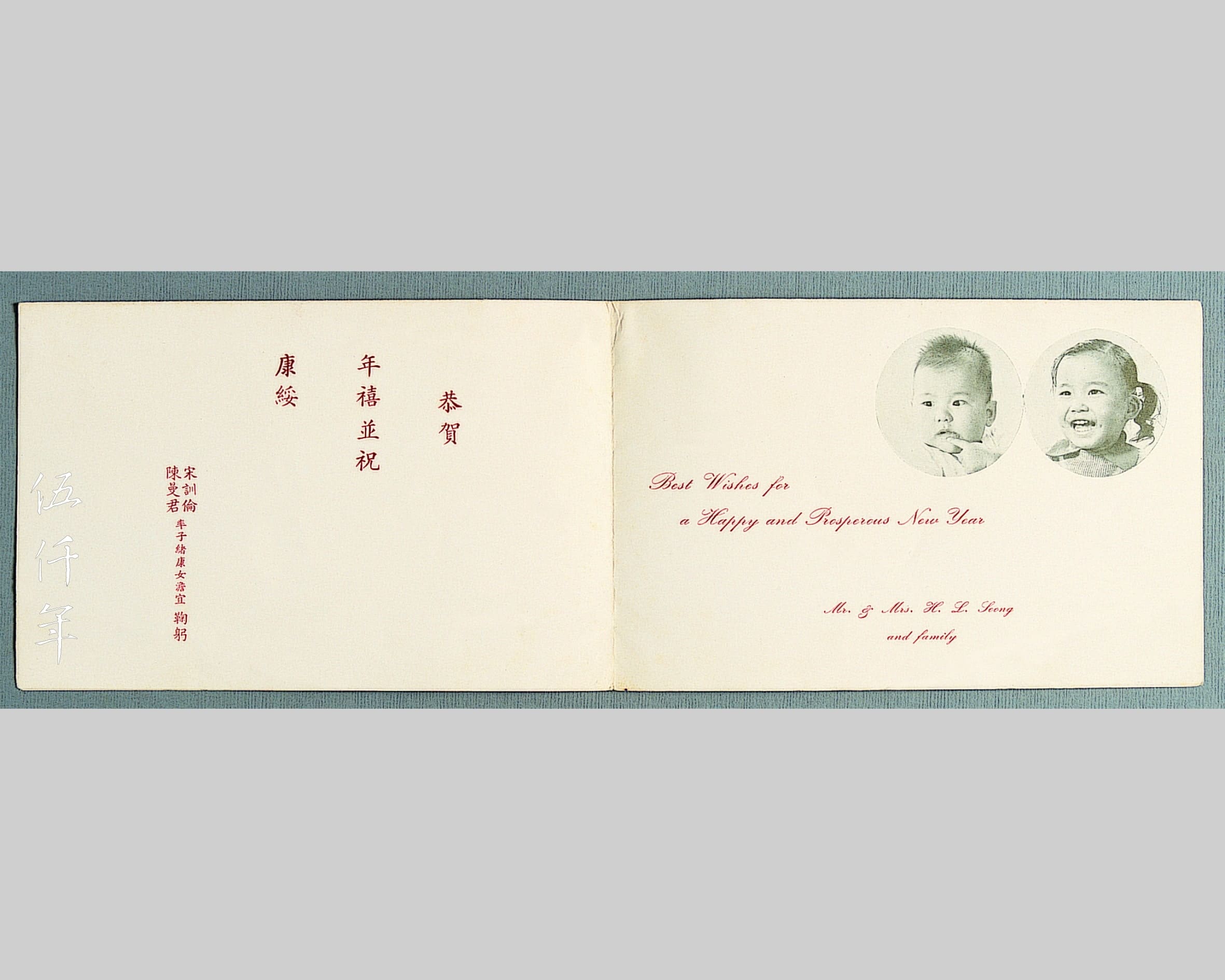

New Year greeting card custom printed by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng with the painting To the tune Che-ku t’ien (鷓鴣天) by Mr. P’u Ju on the cover, and his own tz’u composition To the tune Mo yü erh (摸魚兒) on the back

Inside of the New Year greeting card custom printed by Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

I was so pleased that I made New Year greeting cards with the image of this painting and sent them to friends, as I was moved by the lines in his tz’u lyric To the tune Che-ku t’ien:

In the misty void no sign of my country dear,

But should it appear, how much sadder indeed!

I was reminded of someone who claimed to surpass Li Shih-min (李世民), T’ai-tsung Emperor of T’ang dynasty, and Chao K’uang-yin (趙匡胤), T’ai-tsu Emperor of Sung dynasty, but resulting in such a scale of sufferings and deaths across the country even ghosts wail and deities cry. Mr. P’u was a cultivated gentleman, he expressed his sentiments with sighs and laments. For me, on the other hand, I am an impassioned man, drawing my sword and bow, and smashing the spittoon. I also composed a tz’u lyric To the tune Mo yü erh (摸魚兒), it was printed on the back of the greeting card. It reads:

How bright the moon shines

On the little rowing-skiff;

A light gull rises startled

From the misty islet.

In the vague void,

No trace

Of mountain of river,

But a deep sorrow

Etched in the mist.

The singing and the dancing,

The dazzling spectacles

On the towers and terraces –

They are fair,

But they are not those

Of our homeland.

The river is dammed,

The dream interrupted.

Memories of the taverns of olden days,

Deep in spring;

Painted beams

Where swallows age.

Gazing till the eyes break

Down the road that leads

To the old garden.

Affairs

Of a thousand years;

Vain to speak

Of the Great Emperors

Of the T’ang and Sung dynasties;

Grandiloquent poesy is

Empty

When set beside events

Past and present.

Starving swans

Circle the land,

Weeping for those

Who toil and suffer confinement;

Ghosts cry out,

Men rage.

You need not bemoan;

I will never believe,

That our sacred land

Will remain for ever

In this wretched plight.

Even now, at the

Waning hour of twilight,

There may still be a new move

On the board;

We may still see

Cloud-dragons assemble;

Soldiers and horses

Cross from Heaven.

(Translated by Prof. John Minford)

After printing the greeting cards, Mr. P’u happened to be still in Hong Kong. He was thrilled to see them and took more than a dozen cards. Now a number of years have gone by since Mr. P’u passed away, the rivers and mountains have remained unchanged, but there is no sign of our soldiers and horses. The will of Heaven, the affairs of men, what can one do but sigh!

Mr. P’u was truly unabashedly the master painter of our time. He also represented the classic Chinese scholar. He believed Chinese painting should remain authentically Chinese, it should not incorporate any foreign colours nor ambience. In his opinion, even the paintings of Giuseppe Castiglione (郎世寧 1688-1766) did not qualify to be of the highest standard. This type of unwavering, resolute spirit extended from his art to his daily life, was it not so? His landscapes, flowers and birds, human figures all possess a lofty rhythmic vitality that is unparalleled in this world. At one time, I acquired a meticulously executed portrait of the Goddess of Lo River (洛神) by him. No matter the facial expression, dress fold or overall demeanor, all were purged of ordinariness. He inscribed a poem. It reads:

Gaze across the vast blue water,

Dream to quell waves in the sea.

Recall the Goddess of Lo River Eulogy,

Written in Huang Ch’u (黃初 220-226) reign.

The Goddess rides a fairy bird,

Lost in a flight and never be found.

A thousand year by Lo River shore,

The full moon shines to no avail.

Goddess of Lo River (洛神) by Mr. P’u Ju

Inscription on the painting Goddess of Lo River (洛神) by Mr. P’u Ju

Detail of the painting Goddess of Lo River (洛神) by Mr. P’u Ju

Detail of the painting Goddess of Lo River (洛神) by Mr. P’u Ju

Composing poems and inscribing colophons were his specialties. For most painters, composing poems to accompany their paintings often require some laborious thinking and reciting to perfect the rhythm and rhyme. It will then be copied on draft paper before being inscribed on the artwork. However, after witnessing with my own eyes Mr. P’u’s inscriptions on paintings over a period of two to three months, I was so awed that words cannot fully describe my admiration. It turned out that he did not use any draft paper at all, if there was any draft, it was all in his head. I saw that he painted with full concentration, and on completing the final brushstroke of the painting, he effortlessly lifted his brush and inscribed the poem on top. As his hand painted, his mind was already composing the poem. When the painting was done, the poem was likewise finished. This was at another level of swiftness compared to even those ancient poets who were alleged to be able to compose a poem within seven steps of walking or making eight hand crosses. Not only were the outward forms of “cross” and “step” eliminated, but the literary composition and the pictorial expression were created simultaneously. Even more challenging was that the poem also had to be good. After all, what is the value of an inscription if the poem is not excellent? This was something that I frequently observed, and it was something that impressed me the most, earning my genuine admiration.

That year happened to be the 70th birthday of Mr. Ku Tsung-jui (顧宗瑞先生) which also coincided with his 50th wedding anniversary. Friends asked Mr. P’u to paint a scroll featuring crane and pine for this special occasion. This kind of subject for social purpose would be banal if executed by an ordinary artist. That evening I visited Mr. P’u and saw him prepare the paper and mix the colours. He used the brush with such speed and painted an exquisite and detailed scene of pine and crane. The painting was completed in about half an hour. Lush and elegant, it transported the viewer to a distant place. Before the paint had even dried, he already inscribed a poem:

Canopy of magic mushrooms,

Tribute inside the splendid hall.

Spring orange, filial robe and Han tile,

Signs of happiness unending.

A painting of pine and crane

To honour ahead of time

Your duo centenarian mark

And our country set free at last.

Envy not the mandarin ducks,

A pair carefree in flight.

Fragrance of longevity grass

Pervades the hermit’s robe.

Loving couples are all so blessed,

But to grow old together

Till hair and brows turn white

Is truly rare through time.

The line “Your duo centenarian mark” conveys good wishes and blessings. Mr. Ku and his wife are still healthy and well today so a “duo centenarian mark” is clearly not a problem, but when can “our country set free at last” be realized?

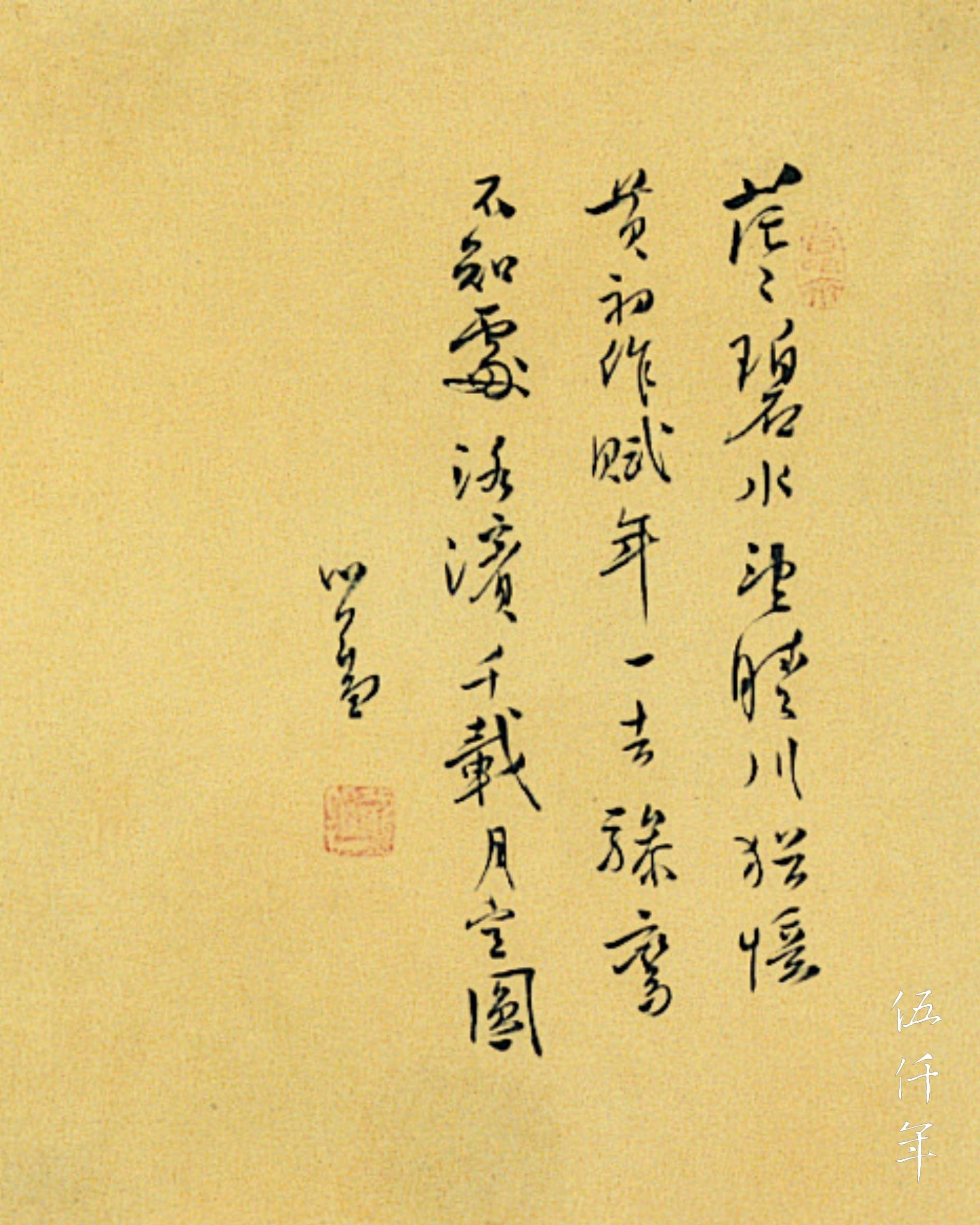

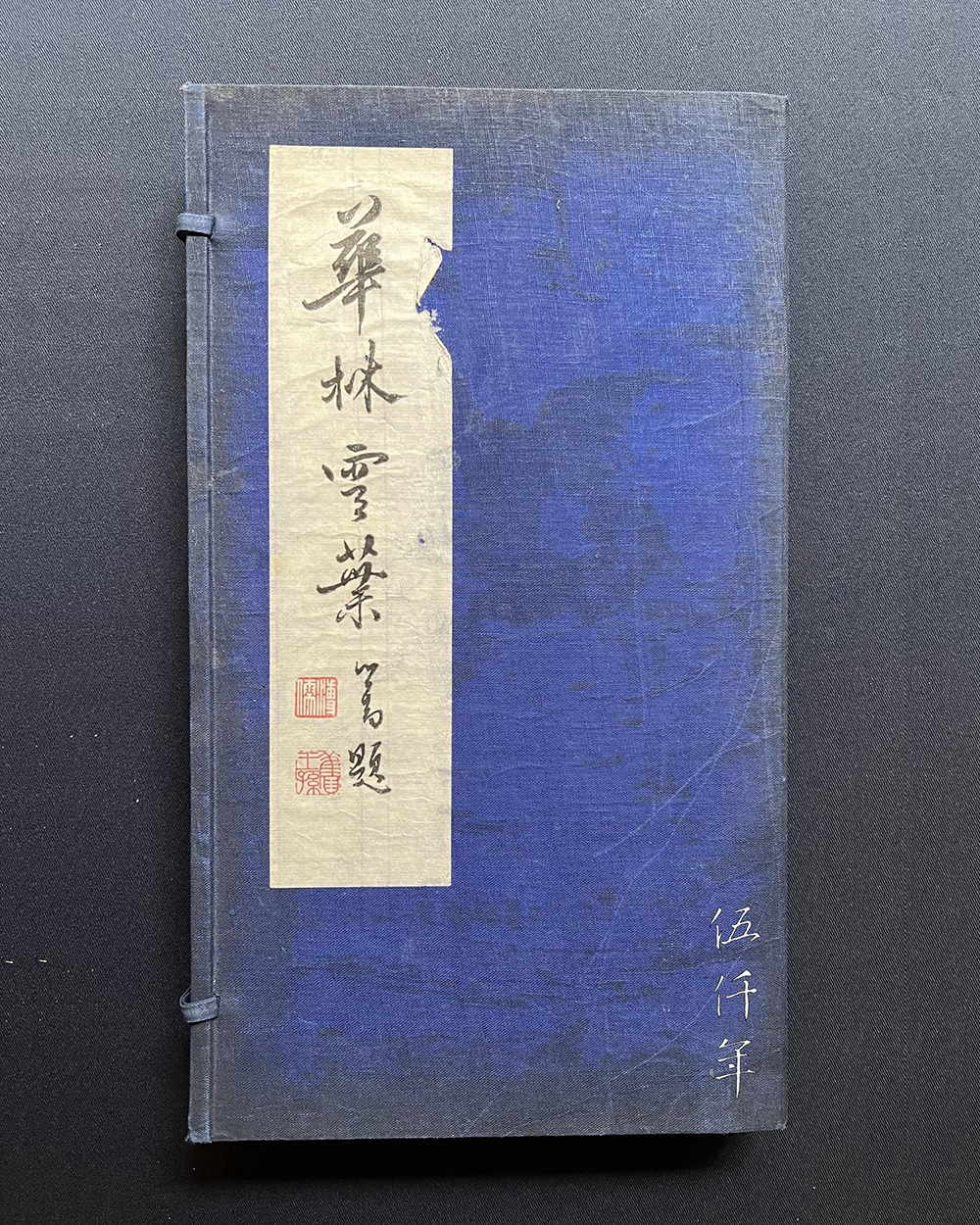

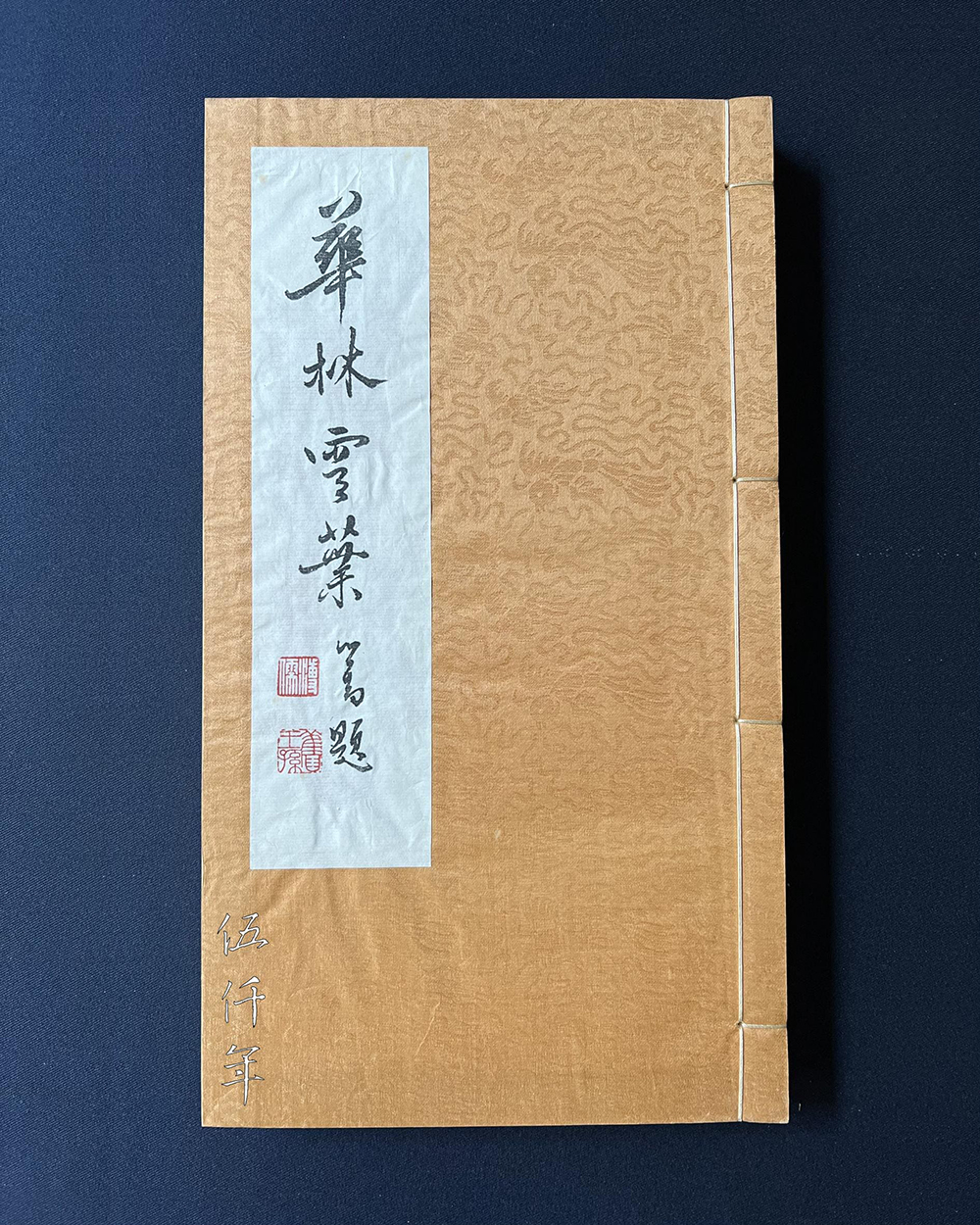

Covering case of Hua-lin-yün-yeh (華林雲葉) by Mr. P’u Ju first published in October of the 52nd year of the Republic (1963) shortly before his death in November

Front cover of Hua-lin-yün-yeh (華林雲葉) by Mr. P’u Ju

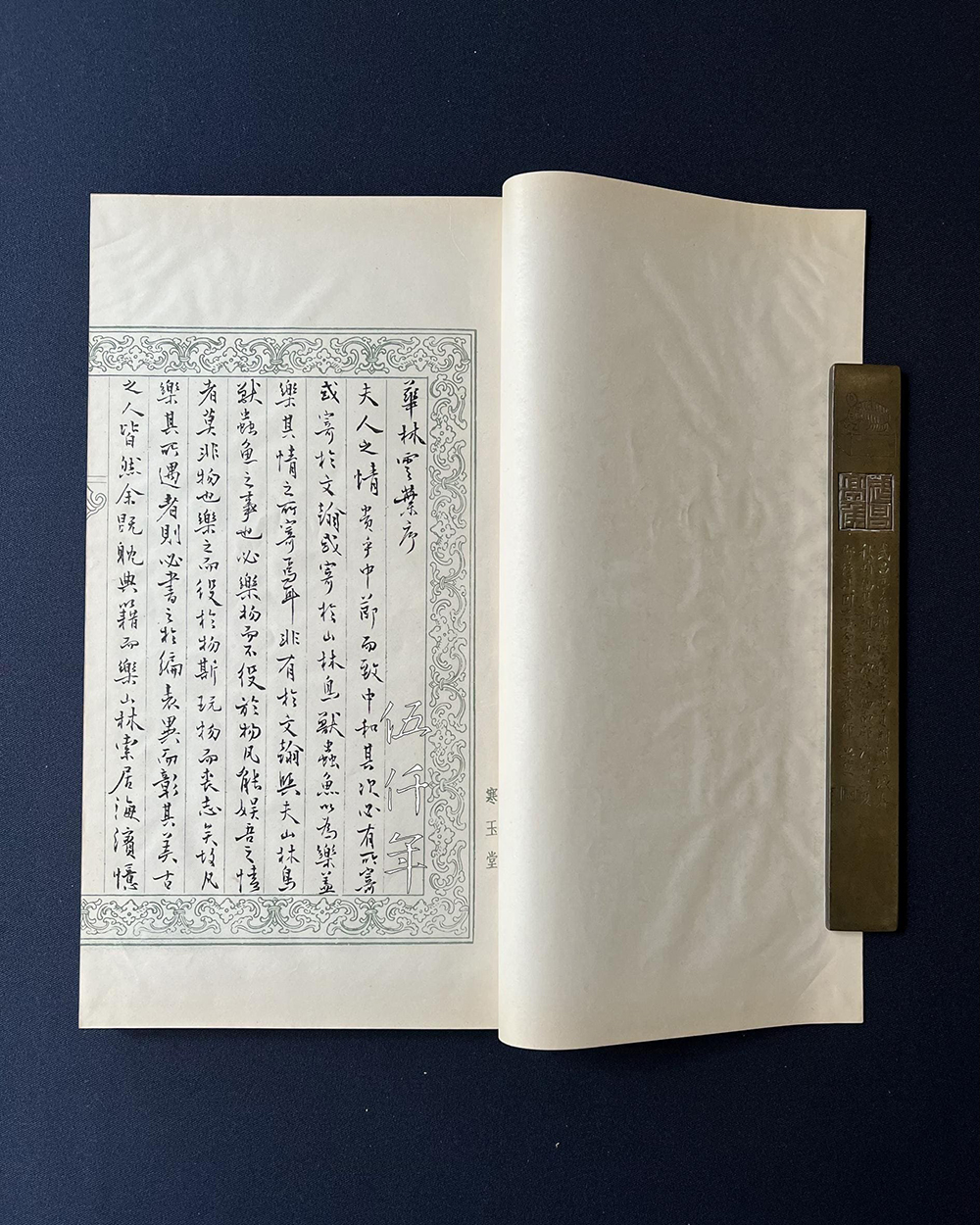

Preface of Hua-lin-yün-yeh (華林雲葉) by Mr. P’u Ju

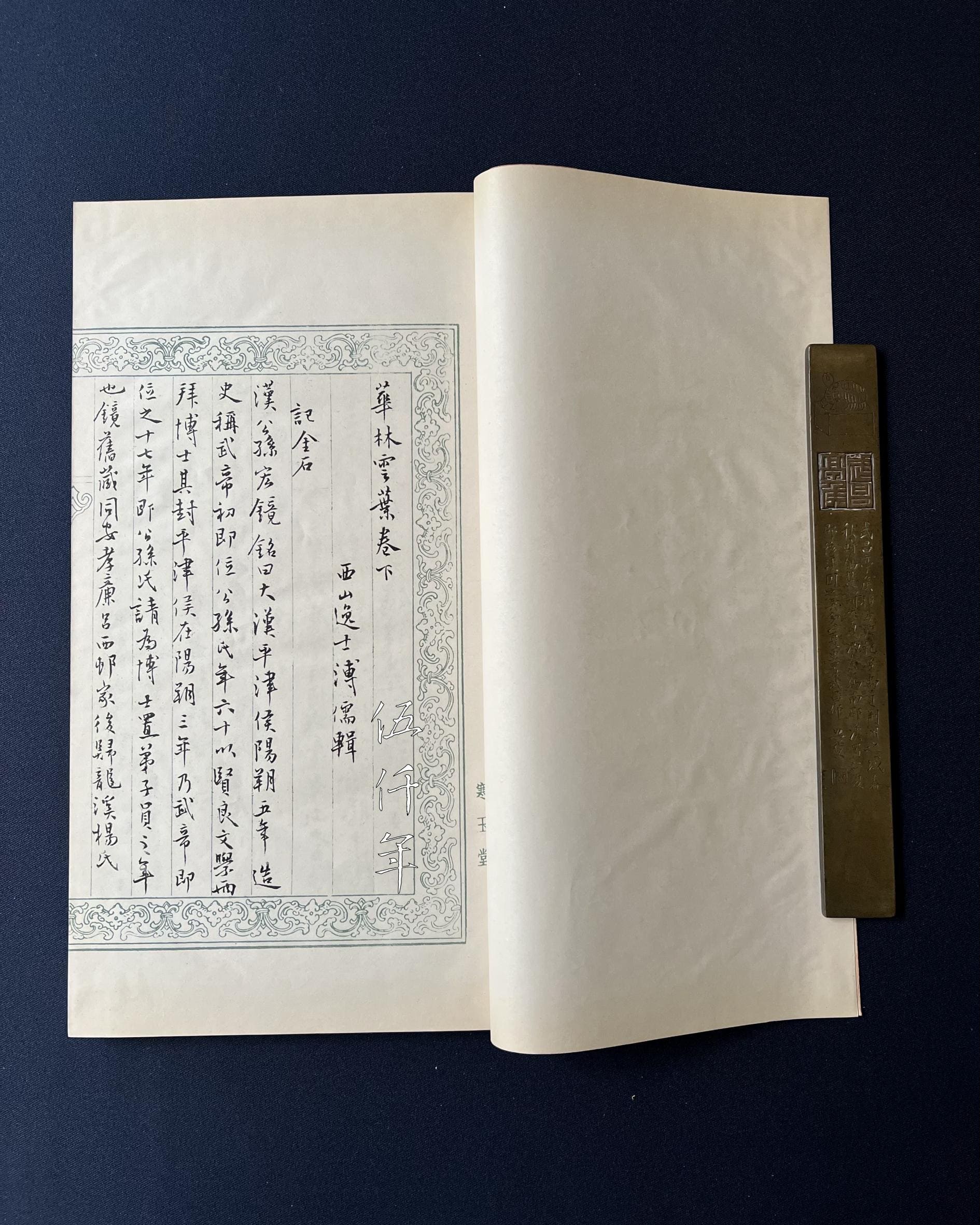

First page of second volume of Hua-lin-yün-yeh (華林雲葉) by Mr. P’u Ju

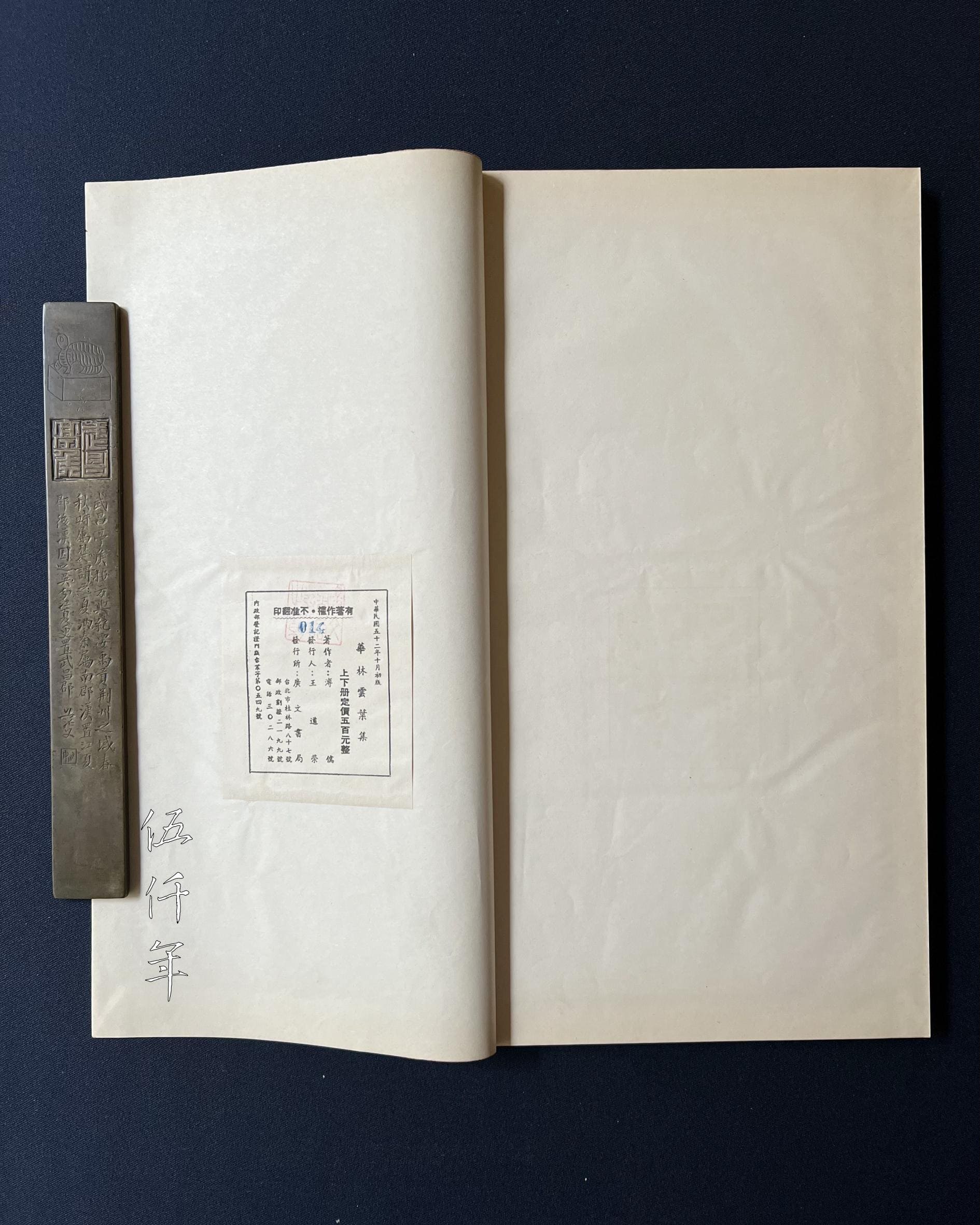

Back page of Hua-lin-yün-yeh (華林雲葉) by Mr. P’u Ju

While I have a copy of Mr. P’u’s work Hua-lin-yün-yeh (華林雲葉), I have not read his Han-yü T’ang Poetry Collection (寒玉堂詩集). Those poems and tz’u lyrics I came across are just a small fraction of his works. However, as demonstrated by the above poem written for the purpose of social intercourse, its style is so tasteful and refined, one can only imagine his other literary works written for personal expressions. It is worth pondering who else in the Chinese art world over the last century had such a combination of scholarship and talent?

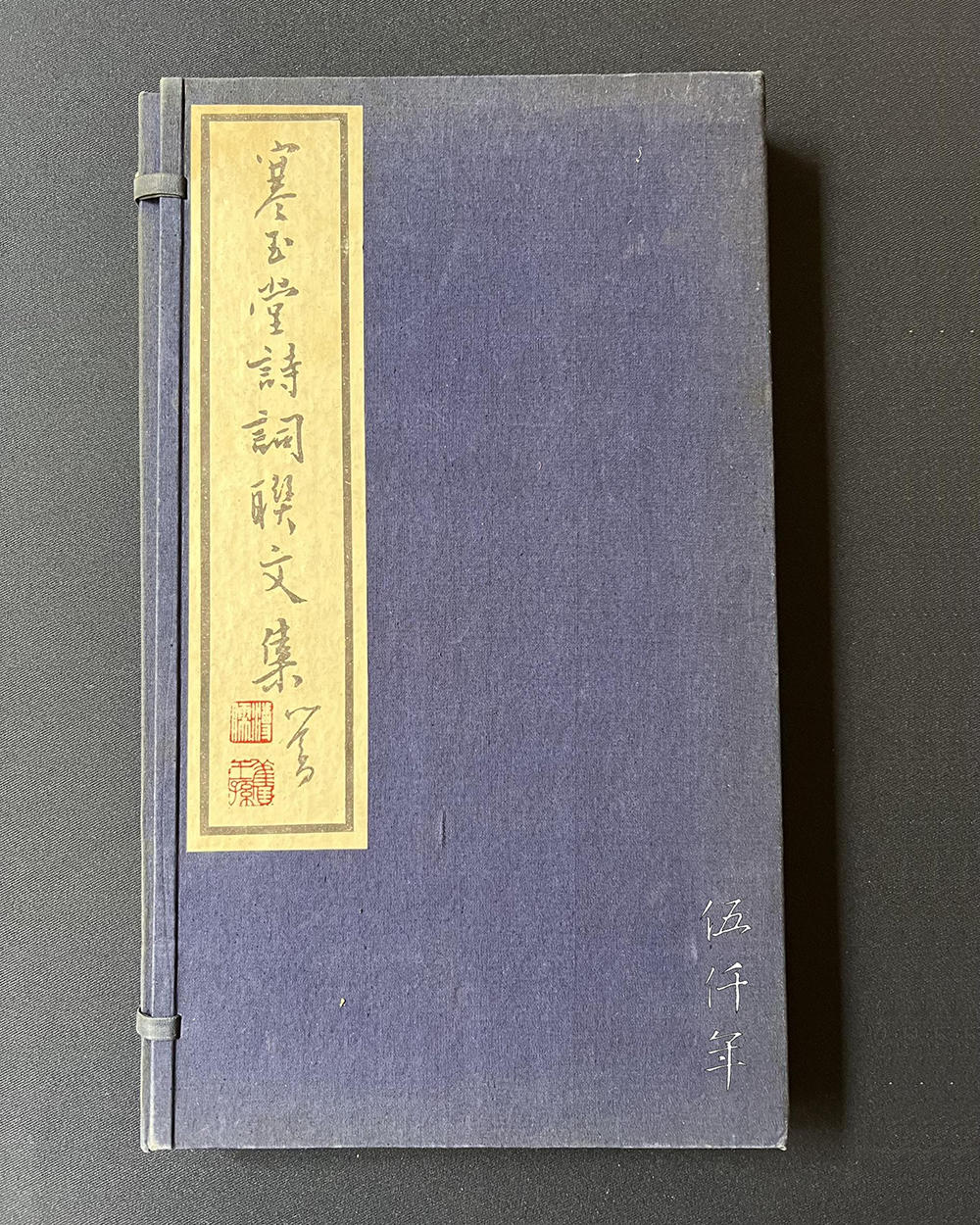

Covering case of The Poems, Tz’u and Couplets of Han-yü T’ang (寒玉堂詩詞聯文集) by Mr. P’u Ju published in December of the 62nd year of the Republic (1973)

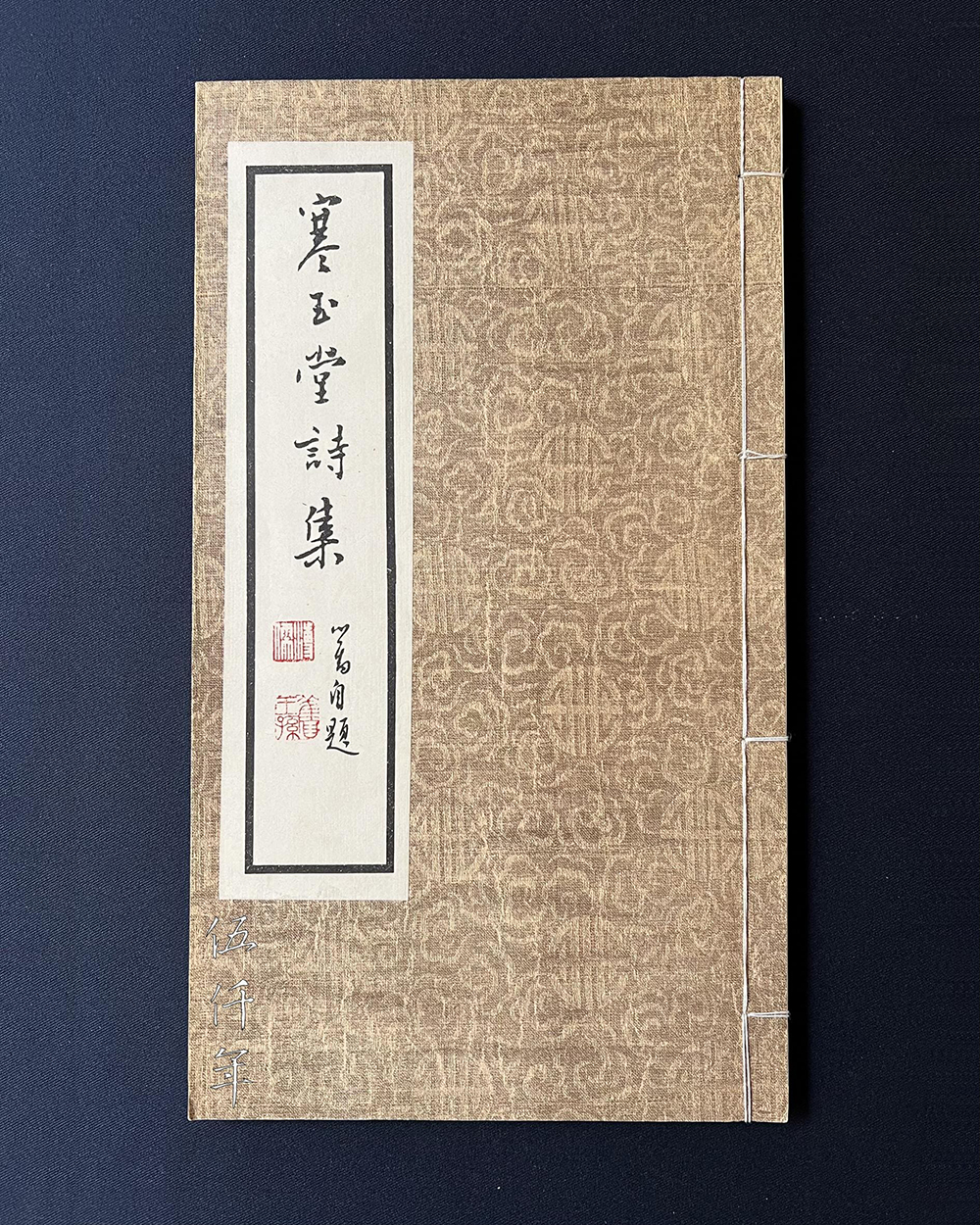

Front cover of The Poems of Han-yü T’ang (寒玉堂詩集), title of the first volume of The Poems, Tz’u and Couplets of Han-yü T’ang (寒玉堂詩詞聯文集) by Mr. P’u Ju

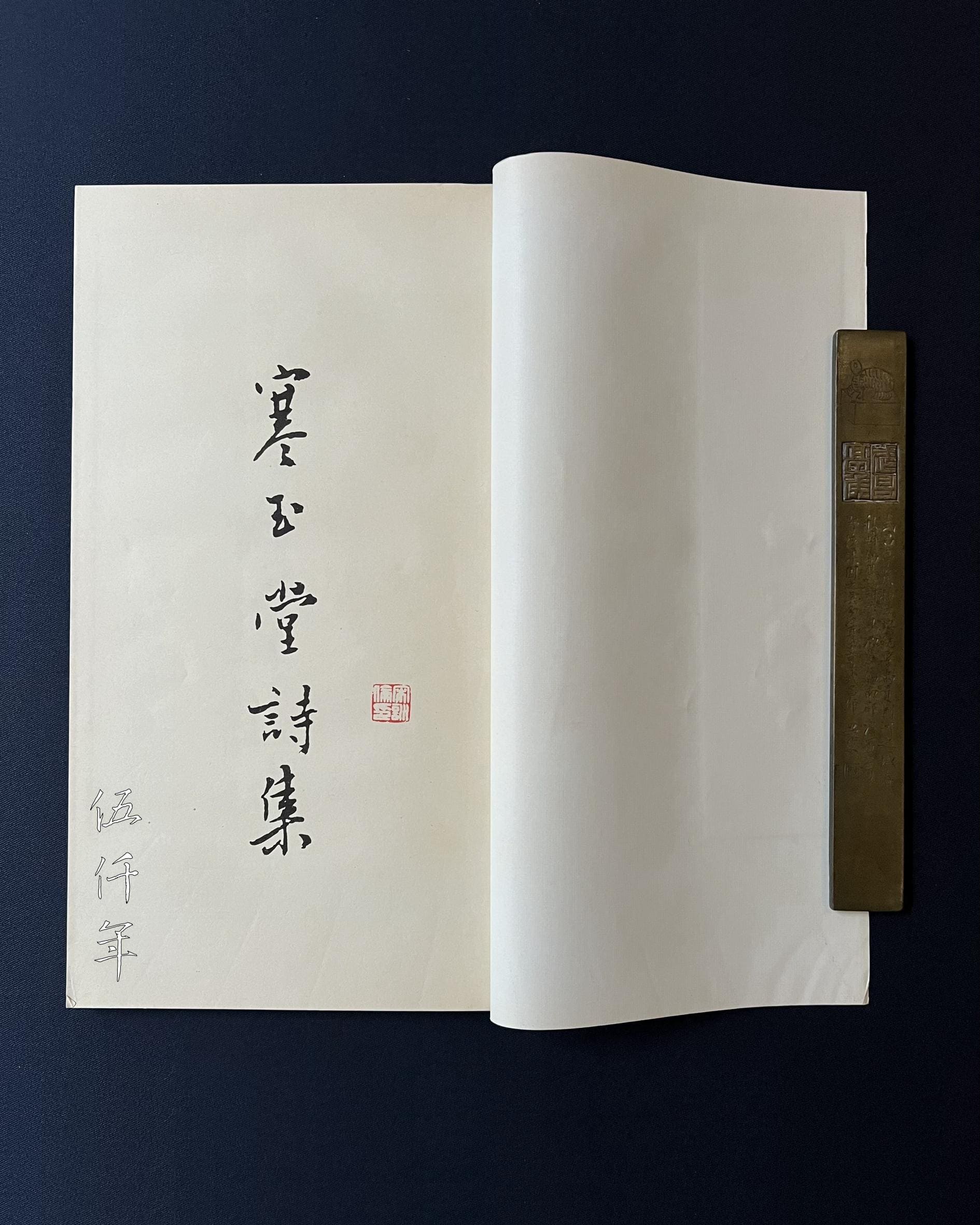

Title page of The Poems of Han-yü T’ang (寒玉堂詩集) by Mr. P’u Ju

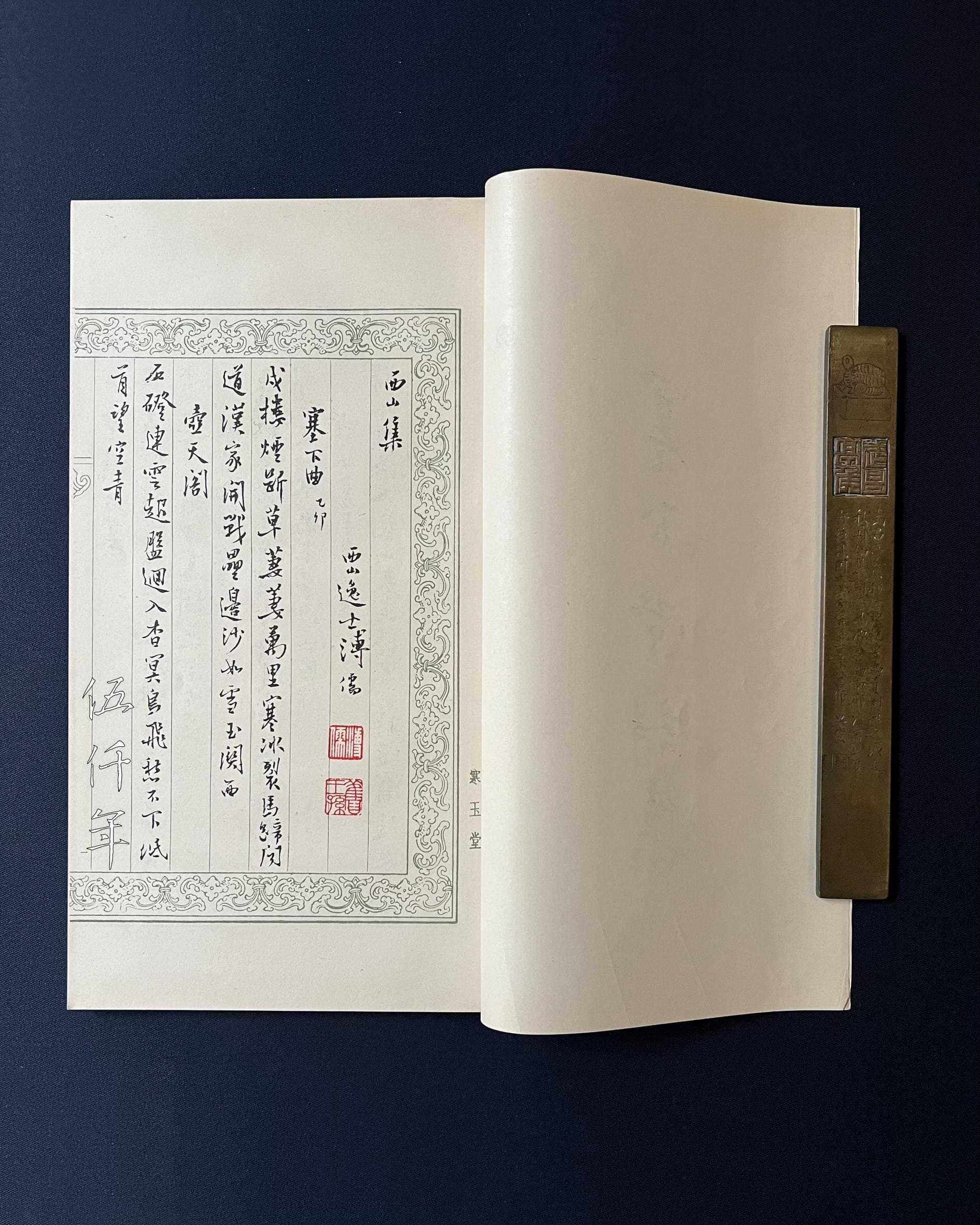

First page of The Poems of Han-yü T’ang (寒玉堂詩集) by Mr. P’u Ju

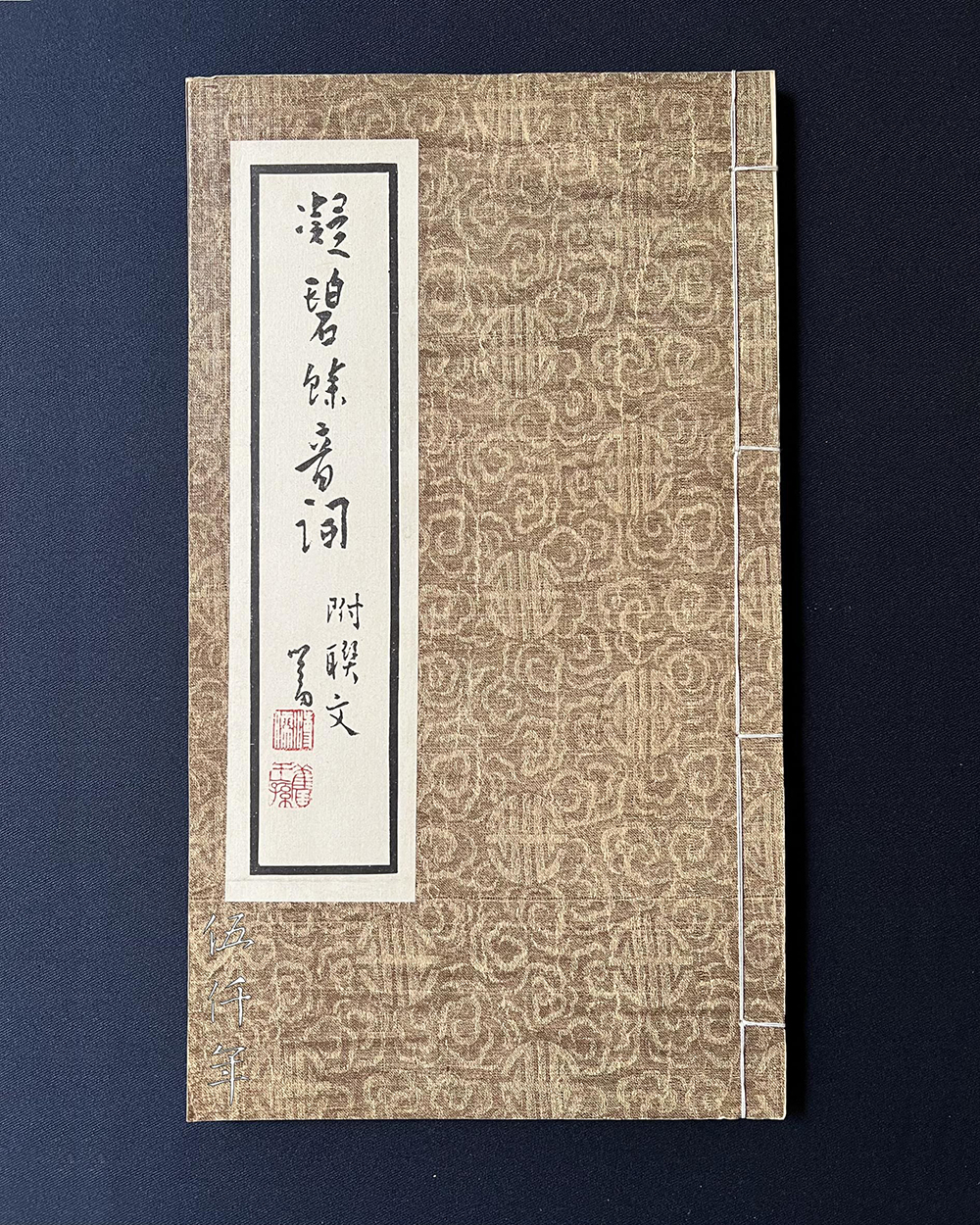

Front cover of Ning-pi yü-yin tz’u (凝碧餘音詞) by Mr. P’u Ju

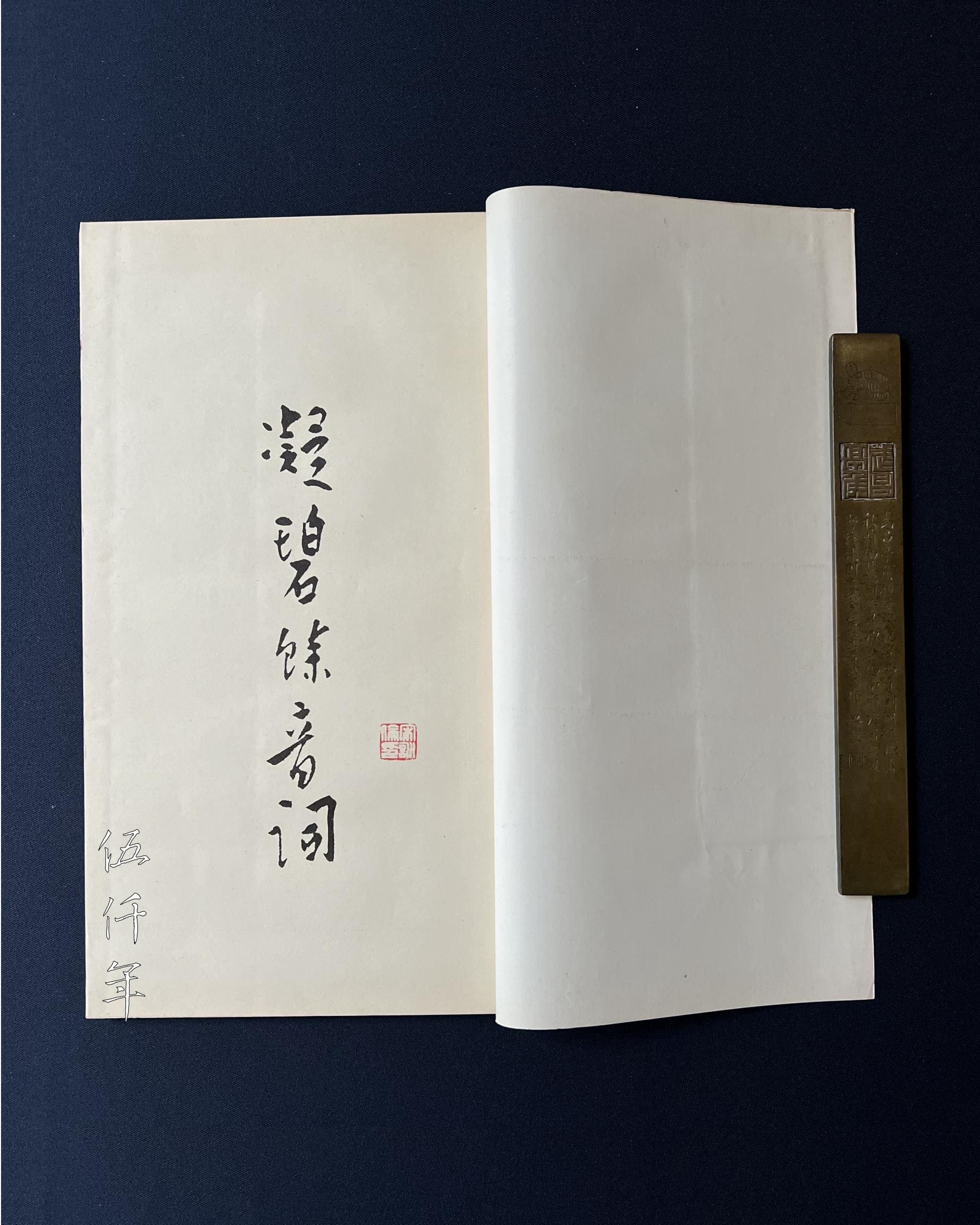

Title page of Ning-pi yü-yin tz’u (凝碧餘音詞) by Mr. P’u Ju

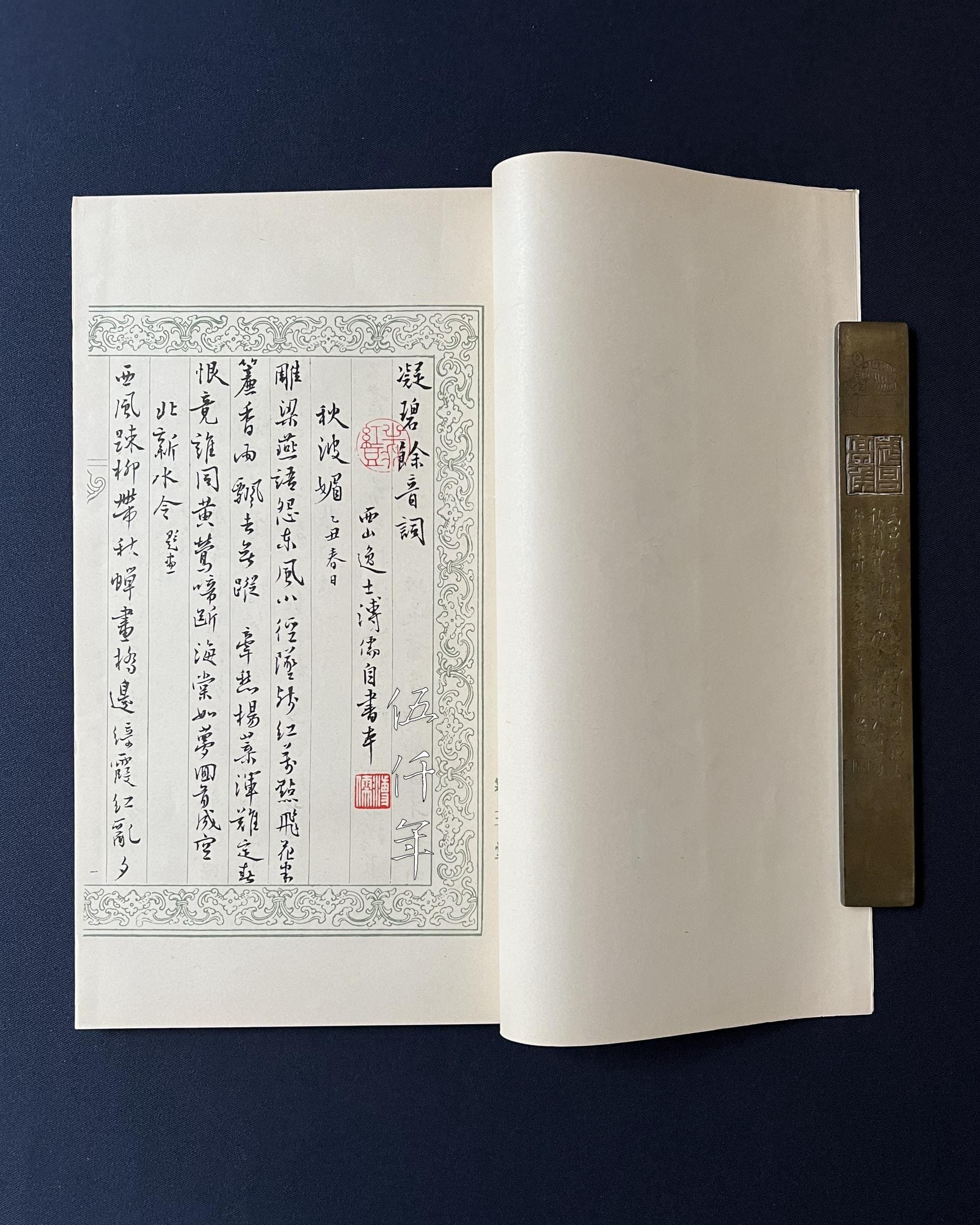

First page of Ning-pi yü-yin tz’u (凝碧餘音詞) by Mr. P’u Ju

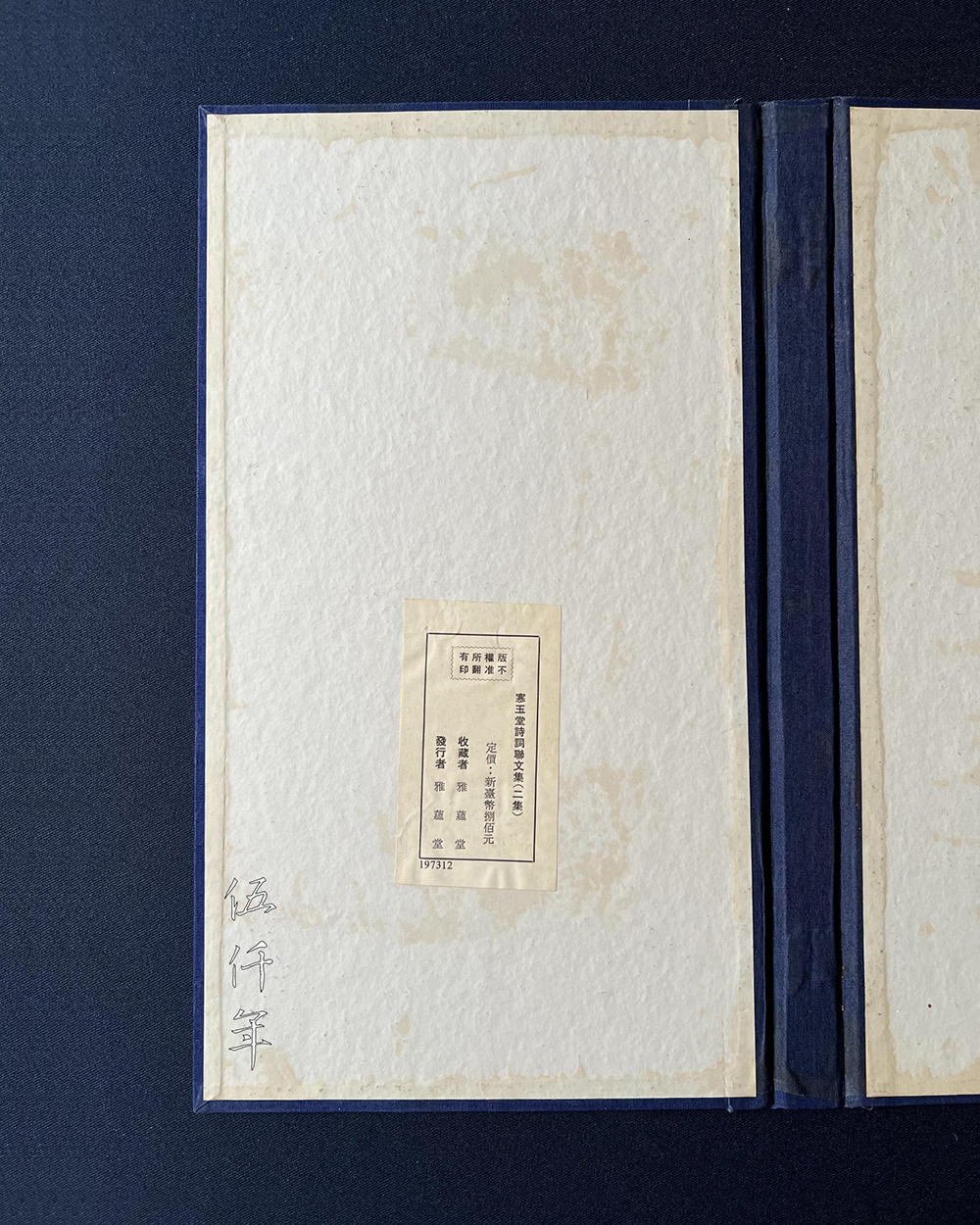

Inside of covering case of The Poems, Tz’u and Couplets of Han-yü T’ang by Mr. P’u Ju

Mr. P’u’s paintings do not command lofty prices in the market, and the prevalence of forgeries is particularly regrettable. However, during his lifetime, he did not care about the values of his works in the market, it is even less relevant now that he has passed away. Artworks that embody truth, beauty, and goodness naturally manifest an enduring spiritual value, how can they be confined by the fashion of the times. In my humble opinion, if we consider impressionist art which has dazed the world today, how long will the world maintain its current fascination is also questionable.

Years from now, when there is peace in the world and well-being in society, people may feel the need to dress a bit more neatly or seek some enrichment or tranquility of the spirit. Perhaps then, in response to the needs of the time, Mr. P’u’s paintings will dazzle once more in their brilliant glory.

Calligraphy of fu (福 meaning Blessing) by Mr. P’u Ju, a gift to Mr. Soong Hsün-leng

Related Contents:

Virtual Homage at the Tomb of Mr. P'u Ju (溥儒)

Calligraphy and Painting, The 2nd Hong Kong Lecture by Mr. P’u Ju (溥儒)

Chinese Literature, Calligraphy and Painting; Text of 1st Hong Kong Lecture by Mr. P’u Ju (溥儒)

On the Common Origin of Calligraphy and Painting, Text of 3rd Hong Kong Lecture by Mr. P’u Ju (溥儒)