Introduction by Mr. Kuo Jo-yu

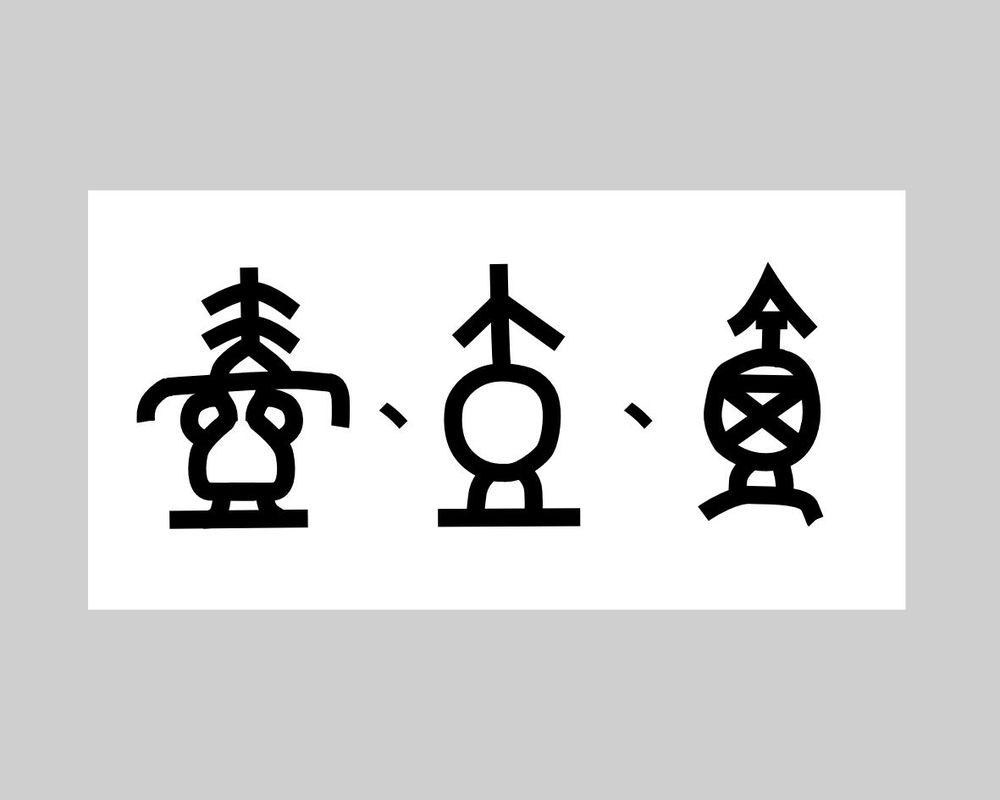

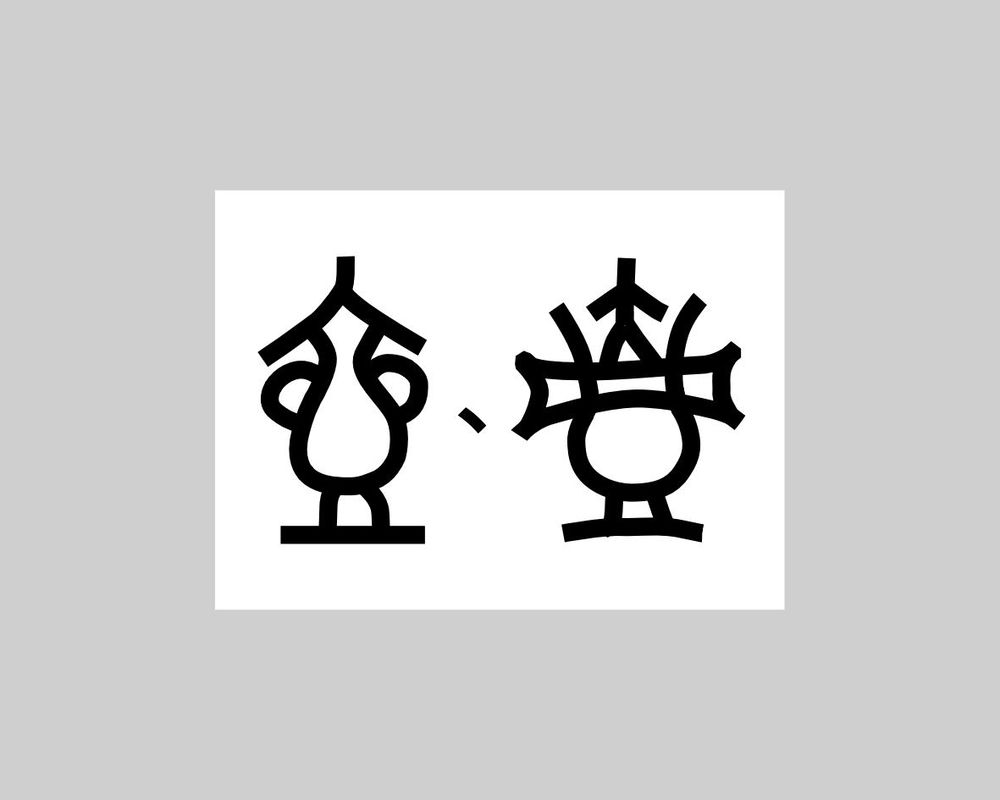

The hu-vessel has existed in China since the Neolithic period. Painted pottery water vessels of Banshan type have been discovered at the site of Yangshao culture in Gansu province dating to approximately four thousand four hundred years ago. InOracle bone inscriptions of the Shang dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BCE) depict hu as having a round body, a small covered mouth and a circular foot at the base. the Western Zhou period (c.1050-771 BCE), the bronze inscription of hu delineates almost the same shape as its counterpart in oracle bone script, only somewhat more ornate. The Shuowen jiezi describes hu as a round bodied pottery jar with cover.

Oracle bone inscriptions of the Shang dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BCE) depict hu as having a round body, a small covered mouth and a circular foot at the base.

In the Western Zhou period (c.1050-771 BCE), the bronze inscription of hu delineates almost the same shape as its counterpart in oracle bone script, only somewhat more ornate.

The Shuowen jiezi describes hu as a round bodied pottery jar with cover.

,瓦器也。古者昆吾作匋。知壺為古代陶器名。

From the Shang dynasty to the Warring States period (475-221 BCE), hu were cast in bronze and used for storing wine. From the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 AD) to the Northern and the Southern dynasties (420-581) there are two types of hu-vessel: round and square. The round one was called zhong (bell), and the square one, fang. These hu vessels were made of bronze. Those made of pottery were used as burial objects. During the Jin (265-420) and Tang (618-907) periods a type of green-glazed ware with a dish mouth, handle and a spout in the shape of a chicken head was known as "chicken head" ewers. During the Tang dynasty hu were also made in gold and silver alongside ceramics. Almost all of them were wine vessels. In the Song dynasty (960-1279), vessels with stands were also a kind of hu. In the Ming dynasty (1368- 1644), ewers with underglaze decoration of floral scrolls were made at the kilns in Jingdezhen. There were two types: tall and short, both with a handle and a cover.

In 1976, a dragon kiln for firing zisha (purple clay) ware was discovered at the Yangjiao Mountain in Yixing. The vessels restored from unearthed shards included a hexagonal hu with appliqué decoration of persimmon design; a round ewer with a dragon-head spout, and a round ewer with an overhead handle.

In 1965, a pair of glazed zisha vessels was discovered in an old well in Qianyao village, Dantao Xian, Jiangsu province. In 1966 a large hu with overhead handle was excavated in Wun Jing’s tomb in Nanjing. These finds show that zisha hu of the early Ming period (14th century AD) were still modelled on the forms of the Song and the Yuan (1271-1368) periods, with hardly any new designs. Legend has it that in the late Ming period, a monk of the Jinsha Temple began making purple clay wares. Since then the art of making purple clay ware passed from generation to generation, creating a unique tradition for purple clay teapots, which survives today.

The monk of Jinsha Temple is said to have moulded purple clay to make hu and other vessels, using his finger prints as the potter’s mark. An official with the surname Wu lived and studied at the temple. His attendant, Gong Chun1, secretly observed the manufacturing process, and after many trials, finally became a master teapot maker. He used the print of his ring fingers as his potter’s mark. The art of teapot making was then passed to Dong Han2, Zhao Liang3, Yuan Chang4 and Shi Peng5. Together they were known as the "Four Masters". Shi Peng taught his son Dabin6 the craft. Dabin imprinted the fingerprint of his thumb onto the handle as his potter’s mark. After Dabin, teapot masters included Chen Zhongmei7, Li Zhongfang8, Xu Youquan9, Shen Junyong10, Chen Yongqing11 and Jiang Zhiwen12.

During the Wanli era (1573-1620), prominent Yixing pot makers rivaling Dabin included Ou Zhengchun13, Shao Wenjin, Shao Wenyin14, Chen Xinqing15 and Chen Guangpu16.

The reigns of Tiangqi and Chongzhen (1621-1644) saw the emergence of prominent Yixing pot makers such as Shao Gai, Zhou Houxi, Shen Junsheng and Chen Chen17.

In the Chongzhen reign few well-known pot makers were recorded in documents, except for four masters, namely Xu Lingyin18, Xiang Busun19, Shen Ziche20 and Chen Ziqi21.

Around this time. Shen Cunzhou from Jiaxing was renowned for making pewter ware. In Chapu [Manuscripts on Tea], Gu Yuanqing mentioned in the section "Choice of Grades" : “Those teapots made of silver and pewter are the best; those of porcelain and stone come second.” Hence we know that silver and pewter tea utensils were highly regarded in the early Qing period. Shen Cunzhou, zi Luyong, was a native of Chunboqiao in Jiaxing. His products comprise mainly pewter pots and cups, both used as wine vessels. Shen Cunzhou once made a pewter dou-cup for Zhu Yizun (Zhucha) as his birthday present. He carved an eight-character inscription in seal script, which reads “Zhuoyi dadou, yiqi huangshou (Drink from this big dou-cup and live long). He also composed a seven-syllabled quatrain which he engraved on its side. This reflects that Shen Cunzhou was also versed in poetry.22

Chen Mingyuan emerged as the foremost pot maker during the Kangxi reign of the Qing dynasty. Original name Yuan, hao Hefeng and Huyin, the Yangxian taoshuo [Discussion of Pottery Wares from Yangxian] mentioned that “Chen made tea vessels and elegant accoutrements by hand. I have seen many kinds, such as a brush rest in the shape of prune roots and the like.

Somehow they may be too delicate. But I admire his calligraphic inscriptions in the style of the Jin and the Tang periods. …… I saw a pot at the studio of my teacher, Fan Tong, with an inscription in the style of Yang Zhongyun : “Dingmao shangyuan wei Duanmu xiansheng zhi [in the fifteenth day of the first month of the dingmao year (1687), made for Mr Duanmu]” In the collection of Wang Shaoshan. There was another teapot inscribed on the base with “Ji ganquan, yue fongming, Kong Yan zhile zai piaoyin [Taking sweet water to brewing fragrant tea, Confucius and his discipline Yan Hui enjoyed drinking from the ladle]. [Chen] Mingyuan was skilled in making replicas of melons and fruit so realistic that they were indistinguishable from the real thing. However, there are many fakes. Authentic ones are hard to come by”.

After Chen Mingyuan those rising to prominence as pot makers included Xu Cijing23, Mengshen24 and Zheng Ninghou25. In the reigns of the Qianlong and Jiaqing emperors, Yang Pengnian was the foremost Yixing pot maker. His brother and sister were also skilled in the craft. Peng did not use moulds to make teapots, preferring to revive the technique of making pots by hand. Though casually formed they showed naturalness. During the Jiaqing reign, Chen Hongshou (Mansheng) was the magistrate of Liyang county. During his office, he designed eighteen forms of teapot and commissioned Yang Pengnian and other potters to make them. He also invited his scholarly friends and associates such as Jiang Tingxiang (1769 - 1839), Gao Shuangquan (1769-1839), Guo Pinjia (1767-1813), and Cha Meishi (1771-1834) to compose and carve inscriptions on the teapots. Some of the inscriptions were composed and carved by him.

Chen Hongshou (1768-1822), zi Zigong, hao Mansheng, Manshou and Zhongyu daoren, was a native of Qiantang (present-day Hangzhou). He was born in the thirty-third year of Qianlong period and died in the second year of the Daoguang reign. In the 6th year of the Jiaqing reign (1801), he passed the civil service examination. Later Chen Hongshou and his cousin Chen Yunbo (1771-1843) served together as the private Secretariats of Ruan Yuan (1764-1849). They were known as the "Two Chens". Later, Mansheng was appointed District Magistrate of Liyang County. Subsequently he was promoted to Sub-perfectural Magistrate of the Waterways Circuit.

Chen was a versatile scholar, proficient in calligraphy, painting and classical literature. He distinguished himself in seal carving and won the honour of being one of the "Eight Masters of the Xiling School". His publications on seal carving included Zhongyu xianguan muyin, Zhongyu xianguan yinpu. His literary works included Zhongyu xianguan ji and Sanlianliguan ji (Anthology of the Hall of Interlocking Mulberries). He was the Magistrate of Liyang county from the seventeenth to twenty-first year of the Jiaqing reign. During this time, he made friends with many scholars such as Qian Shumei, Gai Qixiang and Jiang Xiaoyu. He became acquainted with the famous Yixing teapot makers, Yang Pengnian, his brother Baomian and his sister Fengnian. Having developed a great interest in purple clay teapots, he created a repertoire of eighteen innovative designs. The inscriptions were composed and carved by Guo Pinjia, Jiang Mingxiang, Gao Shuangquan and Cha Meishi, separately or jointly. Then Yang Pengnian would add the final touch before the teapots were fired. These teapots were well received by scholars and literati of the time. They were called "Mansheng hu [Mansheng pots]" or "Man hu".

According to the Qianchen mengyinglu, Chen Mansheng's eighteen teapot designs are:

- Shidiao (conical shape)

- Jizhi (cylindrical shape)

- Queyue (waning-moon shape)

- Hengyun (horizontal-cloud shape)

- Baina (ragged-robe shape)

- Hehuan (chamfered low cylindrical shape)

- Chunsheng (spring-vitality)

- Guchun (spring in the olden days)

- Yinhong (pear-shaped hu)

- Guaxing (melon-shape)

- Hulu (gourd-shape)

- Tianji (heavenly-cock shape)

- Hedou (the shape formed by joining two rice measures with one inverted onto the other)

- Yuanzhu (pearl-shape)

- Ruding (disc-shape)

- Jingwa (tile end-shape)

- Qilian (qi-box shape)

- Fanghu (spuare-hu shape)

Besides these eighteen designs, Chen Mansheng also made the following forms:

- Jinglan (well shape)

- Dianhe (covered-box shape)

- Fudou (covered cup shape)

- Niudou (bell-shape)

- Jingxing (well-head shape)

- Yannian panwa (half-tile shape with an inscription of yannian-extended years, on the side)

- Feihong yannian (half-sphere shape with a goose pattern and an inscription of yannian on the base)

- Tiliang (with overhead handle)

- Douli (bamboo-hat shape)

Chen Manshang derived his teapot designs from a variety of sources. Those inspired by natural phenonena include: Queyue, Yinhong and Hengyun; those inspired by plants include Guaxing and Hulu; those inspired by everyday objects include Dianhe, Fudou, Niudao, Jinglan, Hedou, Qilian and Lixing; those inspired by geometrical shapes include Jizhi, Hehuan, Chunsheng, Yuanzhu and Fanghu, and those inspired by antique objects are Shidiao, Baina, Guchun, Yannian panwa, Feihong yannian, Tianji, Jingwa, Ruding. These designs have profoundly influenced the design of purple clay teapots up to the persent day. It also brought about an unprecedented transformation of the teapot industry for over one hundred and eighty years.

Following Chen Hongshou’s collaboration with Yang Pengnian, Qu Yingshao also collaborated with Yang Pengnian and Deng Fusheng in the production of teapots. Qu Yingshao (1780-1850), zi Ziye, Bichun, hao Yuehu, Qupu and Laoye, studio name Yuxiu tang (Yuexiu Hall), was a well-known scholar and connoisseur in Shanghai. He was awarded senior licentiate in the Daoguang period and was appointed the Sub-perfectural magistrate of Yuhuan. He was a proficient painter of prunus and bamboo, and an expert seal carver. He carved prunus, orchid and bamboo on teapots which were admired and known as "Qu hu". He was also a connoisseur of epigraphs and wrote the Yuehu tihua [Colophons on Paintings by Yuehu] and Yuehu cao [ Manuscripts by Yuehu].

In the wake of Yang Pengnian, there was another prominent pot maker called Zhu Jian (1790-?). A native of Shanyin (present-day Shaoxing), Zhejiang province, his alias was Shimei. He was versed in connoisseurship and was highly creative. He introduced pewter-mounted clay pots. He was skilled in carving and had excelled in engraving on bamboo, stone, bronze and pewter.26 He wtote Hushi [History of Pots].

A pewter lamp made by Zhu Shimei had an inscription in running script verses reading: "The silver candle silently moving the amber shadow, the golden lotus returning to the jade hall mountain", followed by a seal: "old man Jianle at the age of sixty-eight". Another seal-scripted inscription reads, "Shimei made this in Yuanpu in the intercalary 5th month of the 7th year of the Xianfeng reign". From this we can deduce that he was born in 1790. Zhu Jian left-behind his hand-drawn copy of the Jaoye Xingming. There were twenty designs of "Mansheng hu" with illustrations and inscriptions. It is a very valuable source of information on the making of Mansheng teapots.

Other prominent pot makers who were contemporaries of Zhu Jian included Deng Kui27, Huang Yulin28 and Xue Wei29. Huang was a native of Suzhou and made excellent Yixing teawares. Xue was from Shanyang, famous for making teapots.

After the Daoguang period China was unsettled by domestic revolts and the encroachment of Western imperialism. The Yixing teapot industry entered a period of serious decline. The Taiping Rebellion in the Xianfeng period virtually brought the industry to a halt. The final years of the Qing dynasty, however, saw something of a revival. The better-known teapot makers at the time included Fan Changyin, Pan Dahe, Shao Erquan, Shao Jingnan, Wu Yueting (Zhuqi), Feng Caiha, Wang Dongshi and Yu Guoling.

The present catalogue shows some extant pieces made by the famous teapot makers of the Ming and Qing periods, with illustrations and drawings and relevant literature. Most of the material and information compiled has not been published before. It is hoped that this catalogue can be a useful reference in the study of the well-known masters of drinking vessels and their art of the Ming and the Qing periods.

1 According to Wushihu, Gong Chun was an attendant of Wu Yishan. In the annotations of Taiyang baiyong, Zhou Shu mentioned that Gong was Wu’s servant. Li Fang, in Zhonghuo yishujia zhenlue, quoting Wu Qian: “Yishan, original name Shi, zi Kexue, was a native of Yixing. He passed the jinshi degree examination in the jiashu year during the reign of Zhengde (1514), and was appointed an official in Sichuan. ”

2 According to Taoqi keyu, “Dong Han, hao Houqi, initiated and perfected the foliated shape”.

3 Zhao Liang used to make teapots with overhead handles.

4 Yuan Chang may be the person known as Yuan Xi.

5 Shi Peng was active in the Wanli reign (1573-1620) of the Ming dynasty. Together with Dong, Zhao and Yuan, they were called the Four Masters.

6 Shi Dabin, hao Shaoshan, was the son of Shi Peng. Teapots made by him were known as "Shi hu [Shi teapots]". Quiyuan zapei remarks: "Shi hu was well-known, even in remote areas. Initially his teapots followed the forms of Gongchun. His products are simple and elegant. 'Chen hu’ and 'Xu hu’ of the later period could not match the excellence of 'Shi hu’ ”. Zhang Yanchang wrote in Yanxian taoshuo:“My collection has a small octagonal hu by Shi Dabin. On the side, there is an inscription.” Also: “My friend Sha Shangjiu (Renlong) collected a hu made by Dabin with an inscription: "Dabin hand-made in autumn, the eighth month of the Jiachen year. (1604)." Zhang also mentioned: “Lately I have seen a small purple clay teapot at the Jizi studio of Wang Shaoshan…… There is an inscription on the base stating that it was made by Shi Dabin.’ " Chen Zhan mentioned in his Songyanzhai suibi: "While residing at Gang Wuyuan’s place I saw a teapot in the studio of Yishi Liushishiyan. Its base had a ten-character inscription: "A cup of refreshing tea can evoke my poetic mood. Dabin’. The teapot was simple and elegant. It had fine grained texture and a dull red colour like that of pig’s liver."

7 Chen Zhongmei was a native of Wuyuan, Jiangxi province. He was skilled in making fine accoutrements for scholars’ studios, such as perfumer boxes, cups with floral decoration, lion-shaped censers, chimera-shaped paper weights. re-structured engraving and layered carving; teapots in the shape of flowers or fruit, with decorations of insects or dragons playing amid waves. His Guanyin figurines displayed solemn and merciful expressions. He also made parrot-shaped cups. Wu Tianzhuan commended him in fu verses: “The parrot-shaped cup is magnificent with resplendent feathers.” He died in the jiashen year (1644).

8 Li Zhongfang was the son of Li Moulin and the best student of Shi Dabin. His teapots were ingeniously crafted. Some teapots allegedly made by Shi might have been made by Li. There was a saying that: “Big pot made by Li (Zhongfang), inscribed by famous potter Shi (Dabin)”.

9 Xu Youquan, original name Shiheng, learnt teapot making from Shi Dabin. He made various typeforms emulating ancient bronze vessels such as zun and lei, using the colours of the clay to create eye catching combinations. He made many types of teapots including those mentioned in Gudong suoji, which stated that: “Youquan has made the following forms: teapots of lei-jar shape, with cloud and thunder pattern; fan painting; beauty’s shoulder; Xishi breast; wasted foliated petal; of lotus seed shape; chrysanthemum; lotus flower; bamboo joint; olive; hexagonal; melon; and banana section. He also made teapots with handle modeled as the cicada’s wing; as a continuous knot, or as the elephant trunk. ”

10 Shen Junyong, original name Shiliang, followed the school of Qu Zhengchun in the design of teapots. He was already well-known in his youth. He died in the 4 th month of the jiashen year.

11 Chen Yongqing was a co-worker of Jiang Shiying. He made fine forms such as lotus-seed, pu-vessel, alm’s bowl, and round pearl, all with sophisticated decoration. His inscriptions were in the style of Zhong You.

12 Jiang Bokuo, original name Shiying. Yangxian Taoshuo mentioned: “In Songling, at Huayu mansion, Wang Shaoshan showed us a hand-made teapot by Jiang Bokuo of Yixing. Legend has it that this form was specified by Xiang Yuanbian and was called the ‘Tianlaige hu’. ”

13 Zhu Yan mentioned in the Tao shuo: “In the Ming dynasty, there was a man with the surname Ou. He made fine porcelain flower pots and trousseau.” Li Fang also commended him for “making many kinds of flowers and fruits in extremely ornate shapes.” Ou referred to Ou Zhengchun.

14 Shao Wenyin was regarded as “the best in emulating Dabin’s square teapot.”

15 Chen Xinqing excelled in “emulating Shi and Li’s works, not in the style of Chen Yongqing.”

16 Chen Guangpu, “His imitations of Gongchun and Shi Dabin are excellent and delightful to the eye.”

17 Refer to Wang Daxin’s Yesuoji. Wang Daxin, zi Tizi, hao Guling, was a native of Xiuning.

18 Refer to Yixing xian gazette.

19 Xiang Busun, original name Zhen, was a native of Xieli, a descendant of Xiangyigong. Having obtained his senior licentiateship he was given an appointment in the Imperial Academy. Wu Xian remarked, “Busun was not a potter. I saw a teapot in my friend Chen Zhongyu’s collection. It had a three-character inscription of "‘Yanbeizhai’ on the base; and a seal of ‘Xiang Busun’ on its side.” Wang Keyu commended the virtuosity of Busun’s calligraphy in his Shanhu wang.

20 Wu Xian mentioned, “Renhe, Weishu Ziyu recently bought me a teapot with foliated decoration. Inscribed on the base is a three-character verse: ‘Water from beneath rocks, leaves from atop tea shrubs, rinse my teeth afresh and wash away dust and heat’, followed by a signature reading ‘made for Mixian by Ziche’. A teapot formerly in the collection of Jin Yunzhuang of Tongxiang county was inscribed on the base with ‘Chongzhen, guiwei nian Shen Ziche zhi’ [made by Shen Ziche in the guiwei year of the Chongzhen reign].” Shen Ziche was a native of Tongxiang, not Yixing.

21 Chen Ziqi imitated Xu’s teapots. It was alleged that he was the father of Chen Mingyuan.

22 Zhongguo Yishujia Zhengleu after the Naoleng tan: “… In the song on drinking from Shen Cunzhou’s pewter wine ewer, there is a verse which reads: ‘only from this pot, could I drink so much wine’. There is another inscription which reads ‘in the gengse year (1670) of the Kangxi reign’ ”.

23 Zhang Yichang narrated, “Wang Shaoshan’s eldest son, Yizhi has a teapot. The four characters in square clerical script on the base read, ‘Xue’an zhenshang ’. The four-character inscription in regular script reads, ‘Xushi cijiang’. They were inscribed on the lip of the cover, and can only be seen when the cover is lifted open”.

24 Zhang Yanchang also mentioned: “I received a teapot when I was young. On its base was a six-character inscription: ‘Wenxingguan Mengchen zhi’ [made by Mengchen of Wenxing Pavilion].” Wu Xian also mentioned, “Every year on the twenty-ninth day of the sixth month many worshippers flock to Anguo Temple in Haining to present their offerings to the gods. On such an occasion, I acquired a teapot at the fair. There is a seven character verse in running script which reads, ‘The clouds have sailed away towards the ferry in the west, leaving a bright sky’. This was from a Tang poem and was inscribed on its base. On its side is a signature also in running script: ‘Mengchen zhi’ [made by Mengchen]. Though plainly carved, the calligraphy closely resembles that of Chu Suiliang (Henan). ”

25 Wu Xian mentioned, “I have heard that Hu Chaxhi has a teapot, with the seal mark of ‘Zheng Ninghou zhi’ [made by Zheng Ninghou]. The form of the teapot is very elegant. ”

26 In the Zhongguo yishujia zhenglue, Li Fang narrated, “years ago my family had a pewter teapot by Zhu Shimei. It had floral decoration finely engraved all over its body. There was a two-character inscription of Shimei on the base. The handle had a zitan wooden section with inlaid silver thread forming a four-character inscription of ‘Boguzhai zhi’ [made by the Bogu studio]. The craftsmanship was excellent.”

27 Deng Kui, zi Fusheng, was also skilled in making pewter-mounted clay teapots. He once went to Yangxian (Yixing) to supervise the production of teapots on behalf of the Shanghainese potter Qu Yingshao.

28 Mengchuang xiaodu mentioned that Huang Yulin was good in the selection of clay to create colour combinations. Connoisseurs treasured his works and praised that they were even better than those by Yang Pengnian and his brother Baonian.

29 Xue Huai, zi Xiaofeng, hao Zhujun, was the nephew of Bian Shoumin.

Three Masters of Drinking Vessels in the Qing Dynasty By Mr. Soong Shu Kong

Shen Cunzhou

Shen Cunzhou was a renowned maker of pewter wares during the late Ming and the early Qing periods. His extant works include pewter wine ewers, wine dou-cups, tea caddies and water droppers. Cha Li (1716-1783)1 of the Qing dynasty composed a long ballad praising the reading lamp made by Shen, 2which was presented to him as a gift by Wan Guangtai (1717-1755).3 The ballad commended the “ingenious structure” of the lamp that would allow oil to fill up to the brim without overflowing. It could burn all night without refill. Shen Cunzhou had made a breakthrough in mechanical design. Unfortunately this cannot be verified as the lamp is no longer extant, but at least we know Shen made many types of pewter wares.

In the early Qing period, Shen’s virtuosity was well appreciated. However he is little known now, and is rarely mentioned in publications on the art of drinking vessels. When more of his pieces come to light in the future, his creative style, and the types of wares he made will be better understood.

Shen Cunzhou, a native of Jiaxing, Zhejiang province, was so famous for his pewter wares that he was known as “Shen Xi”, Xi meaning tin or pewter. In his Zhongguo meishujia renming cidian (Dictionary of Names of Chinese Artists), Yu Jianhua had grouped Shen Cunzhou and Zhu Yizun as contemporaries, active between the years 1629 top 1709. Though scanty, information about Shen’s biography and accomplishments can be found in old texts and documents.4 he studied poetry under the tutelage of Sheng Yuan (1630-1710).5

Shen Cunzhou was not only a proficient pewter-smith. His designs of various types of wine ewers were also well received by literati and connoisseurs. By inscribing the body of the ewers with his own verses, calligraphy and seal carving, Shen injected literary contents into the art of drinking vessels. According to Naileng tan [Winter Conversations], “…The Yuan and the Ming periods saw master smiths such as Zhu Bishan (c. 1300-after 1362) in silver, Zhang Mingqi (Ming dynasty) in bronze, and Huang Yuanji (Ming dynasty) in pewter. But they were no poets.” For this reason, Shen’s pewter wares are treasured by later generations because of their scholarly appeal enhanced by his skilled poetry and calligraphy.

It is difficult to verify Shen Cunzhou’s circle of acquaintances. From the collected works of poetry entitled Banxiang shihui [Collected Poetry of Fragrant Petals] by Sheng Yuan, we can trace Shen’s extensive group of friends, including Zhu Yizun (1629-1709).6 Shen Cunzhou’s extant pewter pieces also include a wine dou-cup presented to Zhu Yizun on his birthday.7 Shen Cunzhou and Sheng Yuan clearly shared some of their friendships.

The poetry by the Tuoshi Studio entitled Tuoshi zhai shi recorded that the literati of the early Qing dynasty highly praised Shen Cunzhou’s works.8 The pewter dou-cup, seen by Qian Zai, author of the poems by the Tuoshi Studio, was made in 1670. The pewter waler dropper of melon shape by Shen Cunzhou (cat no. 4) was made in 1656, while the pewter octagonal wine ewer of lotus shape (cat. no. 5) was made in 1657, and the pewter wine ewer with overhead handle. (cat. no. 6) was made in 1661.

The first issue of Jinshi shuhua edited by Yu Shaosong in 1934 described a tripod ding-shaped pot by Shen Cunzhou. “This vessel was made by Shen Cunzhou. It has an elegant shape, silver coloured and has a bright reflection. It is 7.5 Chinese inches in height and 5.5 Chinese inches in width. The vessel was inscribed with a seven-syllabled quatrain and a seal “Shen Cunzhou shu” [written by Shen Cunzhou] on the base.”

Shen Cunzhou was unusual among the vessel makers in the Ming and Qing dynasties in being an accomplished designer, equipped with technical skill as well as a practitioner of the other arts. Chen Mingyuan and Yang Pengnian, two important makers of pots during the early and mid Qing periods, were not proficient in poetry and literature. Chen Hongshou and Qu yingshao of the mid Qing periods excelled in the design and engraving of teapots but were not potters. Only after over a hundred years did Zhu Jian play Shen’s dual roles of craftsman and artist.

Artifacts and records showed that Shen Cunzhou was also a versatile calligrapher skilled in regular, running, clerical and seal scripts. He often engraved his poems in regular and running script on his pieces. For the water dropper (cat. no. 4). The inscriptions were written in running script while the four characters reading, “Qingqin shipi” in seal script. Another melon-shaped water dropper in the collection of the Shanghai Museum bears inscriptions dating to the seventh month of the dingsi year (1677) with Shen’s signature in running script, and eight characters in seal script in the upper part. The inscription reading “Zhuoyi dadou, yiqi huangqi” was engraved in clerical script on the inside bottom of a pewter wine dou-cup for Zhu Yizun, with inscriptions and the signature of the artist in regular script on the exterior. A pewter octagonal wine ewer of lotus shape (cat. no. 5) has the inscription in running script, while the pewter wine ewer with overhead handle (cat. no. 6) and the wine cup (cat. no. 7) both bear poetic inscriptions in regular script.

Shen Cunzhou’s seals include those inscribed with “Cun”, “Zhou”, “Cunzhou”. “Zhuju [Bamboo Lodge], “Luyong” and “Yanshi jiuren [Drunken man of the Yan city]”. Judging from the workmanship of the last two seals, he was also a distinguished seal engraver.

Shen Cunzhou’s pewter octagonal wine ewer of lotus shape (cat. no. 5) is the earliest example of mahogany handle. It was a popular feature with the teapots of the Qianlong, Jiajing and Daoguang periods. Chen Hongshou’s pewter teapot of waning-moon shape (cat no. 16); Zhu Jian’s teapot of zither shape encased in pewter (cat. no. 44), melon shaped teapot (cat. no. 45), pewter hexagonal teapot (cat. no. 47), lantern shaped teapot (cat. no. 50) and pewter teapot of ovoid round shape (cat. no. 51), all used mahogany handles. Later Zhu Jian further developed the handle design, decorating it with calligraphy of silver inlay (cat. nos 44, 46, 47, 50).

The octagonal pewter wine ewer of lotus shape (cat. no. 5) has a two-character inscription of “Lianquan” in regular script on its inside botton. After a hundred and sixty-seven years, this practice was also employed by Zhu Jian whose conical pewter teapot (cat. no. 48) has a three-character inscription of “Shimei zuo” [made by Shimei] in clerical script inside its base.

Various media were used to create the knobs decorating the teapot covers. The knob on the cover of Shen Cunzhou’s pewter wine ewer with overhead handle (cat. no. 6), was made of coral. The knob of Chen Hongshou’s pewter teapot of waning-moon shape (cat. no. 16) was made of white jade. The knob of Zhu Jian’s teapot of qin zither shape (cat. no. 44) was made of copper, while those teapots shaped like a measure (cat. no. 45), melon (cat. no. 46), ovoid (cat. no. 49), and lantern (cat. no. 50) have knobs made of emerald green jade, white jade, emerald green jade and emerald respectively. It is evident that these famous pot masters paid special attention to the material used for cover knobs.

Shen was a master pewter-smith who produced a great variety of ewer designs. His renowned shapes include “monk’s cap”, “lotus” and “peach-stone”.9 The pewter octagonal wine ewer of lotus shape (cat. no. 5) is a typical example of his renowned lotus-shaped pot, while the pewter wine ewer with overhead handle (cat. no. 6) represents a revival of earlier form. A tripod ewer by Shen Cunzhou was illustrated in the first issue of Jinshi shuhua [Epigraphy, Calligraphy, and Painting] edited by Yu Shaosong in 1934. These are evidences of a wider repertoire of forms.

Apart from considering the forms of the pots, Shen Cunzhou also paid attention to the materials and relationships between the cover knobs and handles. He was innovative in incorporating poems, calligraphy and seal carving as decorations on the body. He surprised the drinkers with calligraphic engravings inside the ewers and cups. Seals of different sizes on the body or base of the vessels also greatly enhanced the appeal of the ewers to literati taste. Shen had a profound influence on opt makers of later generations through his synthesis of design. Craftsmanship and the arts. He was a model for later literati potters such as Chen Hongshou, Qu Yingshao and Zhu Jian. Today, after the elapse of three centuries, the pewter wares of Shen Cunzhou are particularly inspirational.

Apart from considering the forms of the pots, Shen Cunzhou also paid attention to the materials and relationships between the cover knobs and handles. He was innovative in incorporating poems, calligraphy and seal carving as decorations on the body. He surprised the drinkers with calligraphic engravings inside the ewers and cups. Seals of different sizes on the body or base of the vessels also greatly enhanced the appeal of the ewers to literati taste. Shen had a profound influence on pot makers of later generations through his synthesis of design, craftsmanship and the arts. He was a model for later literati potters such as Chen Hongshou, Qu Yingshao and Zhu Jian. Today, after the elapse of three centuries, the pewter wares of Shen Cunzhou are particularly inspirational.

QU YINGSHAO

Qu Yingshao (1780-1850), zi Ziye, Bichun, hao Yuehu, Qufu, and Laoye, had the studio name of Yuxiutang. He was a prominent scholar in Shanghai, and the Molin jinhua [Contemporary Remarks on the lnk World] judged his painting and calligraphy to be executed in the style of Yun Shouping (1633-1690). His biographical details were recorded in a number of ancient records.10

Qu was a well-known pot master in the reign of Emperor Daoguang. Younger than Chen Hongshou by thirteen years, and older than Zhu Jian by eleven years, Qu excelled in painting bamboo in elegant and spontaneous brushwork. He was also an expert seal engraver but did not carve many seals. Qu modeled his teapots after those by Chen Hongshou, producing exquisite works in his own unique style, and were treasured by his contermporaries. He was also a connoisseur of antiquities and an expert in epigraphy. His works included Yuehu tihuashi [Poetic Colophons by Yuehu] and Yuehu cao [Manuscripts of Yuehu].

Qu Yingshao was proficient in engraving inscriptions on pots. Potters who collaborated with him included Deng Kui (Fusheng). Yang Pengnian and Shen Xi; all of whom were active during the Jiaqing and Daoguang eras (1796-1850). According to the Yangxian shahu tukao [Illustrated Study of Purple Clay Teapots from Yangzian] by Li Jingkang and Zhang Hong. “Ziye tried to make purple clay pots, naming himself Hugong (meaning the master of pots). He commissioned Deng Fusheng to supervise the making of pots in Yixing. His teapots were engraved with self-composed inscriptions, or paintings of bamboo and prunus by Ziye. They are known as Sanjue hu [Pots of three perfections]. He continued the tradition of inscribed teapots after Chen Hongshou. Those pots which were used as ordinary gifts, had inscriptions written and inscribed by Deng Fusheng.”

We can have a better understanding of the life of Qu Yingshao through his book Yuehu tihuashi [Poetic Colophons by Yuehu], which was first published in the thirtieth year of the Daoguang reign (1850). His good friends Zhang Dan11, Liu Shu12 and Su Weiren13 each wrote a preface for it. Their friendships were fostered by their common pursuit of poetry. Occasionally they would meet to comment on each other’s latest verses. In this catalogue, there is a piece of calligraphy featuring poems written by Qu Yingshao, Liu Shu and Mo Shuyu14 dedicated to Liquan (cat. no. 39). In their respective prefaces, Zhang, Liu and Xu all commended Qu’s proficiency in poetry, calligraphy and painting of bamboo. They all expressed their grief at Qu’s sudden death, and mentioned that Qu’s eldest son, Shaochun, had tried to gather his father’s poems for publication.Unfortunately, he found that most of the manuscripts were lost when the family fled the battle in the renyin year (1842)15. Finally aided by his father’s friends, Shaochun was able to assemble a number of Qu’s poems and verses by salvaging them from his poetic inscriptions on paintings, and published them in Yuehu tihuashi [Poetic Colophons by Yuehu].

The following two poems were taken from Yuehu Tihuashi, a compilation of seventeen poems in five-syllabled quatrain and 162 poems in seven-syllabled quatrain. These untitled poems mostly describe bamboo, and occasionally prunus, pine, bamboo and rock orchid and bamboo, as well as orchid and rock. Two poems in seven-syllabled quatrain are listed below:

A day in the mountains is as long as a year,

Bamboo shoots spreading young branches green and pretty;

Where comes the melodious tune of qin-like refrain,

Deep in the green forest a murmuring stream.

Below the sea of clouds greenness is overwhelming

Too vast to contain the valleys and mountains,

Grudge not for painting so many unyielding joints

Look at the fresh breeze through my sleeves.

A teapot of conical shape engraved with bamboo designed by Qu Yingshao and Yang Pengnian (cat. no. 29) was stamped with a seal mark of “Pengnian” on the underside of the handle. Yixing zisha zhenhang [Appreciation of Purple Clay Wares of Yixing] edited by Gu Jingzhou illustrated three teapots made by Yang Pengmian and inscribed by Qu Yingshao.16 The first piece is a teapot of conical shape with engraved bamboo decoration housed in the collection of the Shanghai Museum, with a seal mark of “Pengnian” on the underside of the handle, which is very similar to cat. no. 29 in terms of form and inscription. The second piece is a teapot of ovoid shape owned by the Shop of Cultural Relics in Suzhou, with the mark of “Yang Pengnian zuo [made by Yang Pengnian]” on the base. The third piece is a teapot of conical shape in the collection of Tang Yun, also with a seal mark of “Pengnian” on the underside of the handle. There is a teapot of conical shape made by Shen Xi and inscribed by Qu Yingshao and with the oblong seal of “Shen Xi” in the K S Lo Collection of the Flagstaff House Museum of Tea Ware.17

Qu Yingshao engraved calligraphic inscriptions in running script. There are no examples of his use of regular, clerical or seal scripts in extant pots. He was fond of engraving his poetry, verses and paintings on the body of the pot. The insriptions were engraved in vertical or horizontal alignments. Those engraved in horizontal alignment are rarely practiced by other pot makers. Two examples can be found in cat. nos 29 and 30 of this catalogue.

The locations of seals stamped on the pots by Qu Yingshao are varied. His seals include “Yuehu”, “Jihu” in square or gourd shape, “Hugong yefu”, “Ziye jihu”, “Yiyuan”, Letaotao shi”. “Ji’an” is the seal he used to stamp the underside of handles. The signatures on the pot include “Ziye” and “Yuehu”. He also inscribed the character “Ye” on the tip of the spout, which is only seen in a conical shaped teapot with bamboo and orchid decorations (cat. no. 30). Such features also distinguish him from the other potters.

Qu Yingshao was proficient in painting bamboo, with a number of works extant. Bamboo (cat. no. 33), Flowers (cat. no. 34), Orchid, bamboo and rock (cat. no. 35) and two folded fans with calligraphy and bamboo (cat. no. 36) as well as calligraphy and orchid (cat. no. 37) all display his spontaneous and free-hand painting style. Apart from bamboo, he also painted orchid, prunus and willow. He favoured extending the painting design to the cover of the teapots to fully express the natural growth of orchid and bamboo. (cat. no. 40) and his personal jade seal engraved with “Ziye” (cat. no. 41). He also engraved bamboo as seen in the ink rubbing of the bamboo rib of a folding fan (cat. no. 38). There is also an ink rubbing of an inkslab of eared-cup shape (cat. no. 43) engraved by Qu. The two seals and ink rubbings suggested that Qu was an engraver of a rich variety of media.

In retrospect, Qu Yingshao’s poetry, calligraphy and painting, as well as his art of pot-making were executed in an instinctive and spontaneous manner. The unique style of his works conveys the dilettante spirit of a scholar. While his contemporary pot master Chen Hongshou rarely adorned his pots with painting, Qu combined the art of pot-making with his poetry, calligraphy and painting, the so-called “Three Perfections”. This made Qu’s pots precious objects for later generations.

ZHU JIAN

Zhu Jian (1790-?), zi Shimei, hao He daoren, Mei daoren, Laomei (in his later years), was a native of Shanyin (present-day Shaoxing, Zhejiang province). He resided in Songjiang (present-day Shanghai) and named his studio Boyazhai. He had a wide circle of friends including Gail Qi (zi Qixiang). Besides being proficient in painting prurus, he was also an accomplished maker of pewter teapots, engraving calligraphy and painting to decorate them. His vessels were highly praised and compatible to those by Chen Hongshou.18

The extant works of Zhu Jian can be classified into purple clay and pewter vessels. The categories of objects include teapots, tea caddies, wine cups, water pots, seal-paste boxes, pewter lamps and others. According to the Yangxian shahu tukao [Illustrated Study of Purple Clay Teapots from Yangxian], works by Zhu Jian include two large purple clay teapots in the collections of Bishanhu guan and Ou Mengliang, and a purple clay teapot dedicated to Song Mingxiang. The Zisha hu jianshang [Connoisseurship of Purple Clay] recorded a purple clay teapot of foundation stone shape with rounded corners, formerly in the collection of Tang Yun. This catalogue illustrates eight pewter teapots (cat. no. 44-51) and four pewter wine cups (cat. no. 52-55) as well as an inkslab dedicated to Gai Qi (cat. no. 56) by Zhu Jian.

According to the Molin jinhua [Contemporary Remarks on the Ink World], Zhu “sometimes executed ink painting of prunus, he was an expert seal engraver and proficient in engraving bamboo and rock on copper and pewter wares in an exquisite manner.” Prunus (cat. no. 57) is a rare ink painting by Zhu Jian. Another fan painting of Fruits and flowers by Zhu Jian (cat. no. 58) is also featured in the catalogue. Both reflect Zhu’s style of painting. Although Zhu was celebrated for his seal-engraving, no examples of his seals are extant today.

From the existing examples of purple clay and pewter teapots, and a few paintings by Zhu Jian, we are able to gather some information about his social circle. His acquaintances included:

1.Song Mingxiang, original name Dazun, zi Zuoyi, was the author of the Xueguji [Collected Works of Classical Learning]. The Yangxian shahu tukao mentioned that Zhu Jian made a pot for him, bearing inscriptions by Guo Lin, Chen Hongshou and Ling Yu.

2. Guo Lin (1767-1831), zi Xiangbo, hao Pinjia, was a native of Wujiang, Jiangsu province. He was versed in ci-lyrics, essays, and seal-engraving. Occasionally, he painted bamboo and rock. In calligraphy he followed the style of Huang Tingjian (1045-1105). His works include Lingfenguan ji ji ci ji [Literary Works and Ci-lyrics of the Lingfeng Studio] and Jinshi libu [Supplementary Practices of Epigraphy].

3. Chen Hongshou (1768-1822), zi Zigong, hao Mansheng, was a native of Qiantang (present-day Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province). He passed the civil examination in the sixth year of the reign of Jiaqing (1801), and then rose to the rank of Associate Administrator of Huai’an. He was proficient in poetry, essays, calligraphy and painting. His seal carving followed the tradition of the Four Masters of Xiling. His works include Sanliantiguan shiji [Collected Works of Poetry of Sanlianliguan] and Chongyu xianguan yinpu [Album of Seal Marks of Chongyu xianguan].

4.Ling Yu was a native of Fanou (present-day Guangzhou, Guangdong province). He was the author of Shuyunzhai ji [Collected Works of Shuyunzhai].

5. Xu Guilin used the studio name Youwei wuwei zhai. Yangxian shahu tukao mentioned that one pot by Zhu Jian was engraved with the mark of “Youwei wuwei zhai” on the base.

6. Zhu Henian, zi Yehe, was a native of Weiyang. He was a proficient landscape painter. Together with Zhu Weibi and Zhu Shushi, they were known as the “Three Zhus”. Yangxian shahu tukao [Illustrated Study of Purple Clay Teapots of Yangxian (Yixing)] mentioned that one pot by Zhu Jian was engraved with the mark of “Yehe” on the base.

7. Lianpu, biography unknown.

(A seal box by Zhu Jian formerly in the collection of Tang Yun has an inscription: “Lianpu taishi zhu” [at the request of Lianpu taishi]).

8. Qinfang, biography unknown.

(Yixing zisha zhenshang [Appreciation of Purple Clay Wares of Yixing] illustrated a teapot by Zhu Jian in the collection of the Shanghai Museum bearing an inscription: “Qinfang xiansheng qingwan” [for the refined pastimes of Mr Qinfang]).

9. Langxuan, biography unknown.

(A teapot by Zhu Jian in the K.S. Lo Collection housed in the Flagstaff House Museum of Tea Ware has an inscription: “Langxuan erxiong qingwan” [for the refined pastimes of Zhuquan]).

10. Zhuquan, biography unknown.

(The purple clay teapot of qin-zither shape encased in pewter by Zhu Jian (cat. no. 44) has an inscription: “Zhuquan liuxiong qingwan” [for the refined pastimes of Zhuquan]).19

11. Yinzhi, biography unknown.

(The purple clay teapot of qin-zither shape encased in pewter by Zhu Jian (cat. no. 44) has an inscription: “Yinzhi chizeng” [presented personally by Yinzhi]).

12. Fangquan, biography unknown.

(The pewter teapot of measure shape by Zhu Jian (cat. no. 46) has an inscription: “Fangquan xianshan” [Mr Fangquan]).

13. Zhu Fangzeng, hao Hongfang, was a native of Haiyan, Zhejiang province. He passed the jinshi degree in the civil service examination in the sixth year of the Jiaqing reign (1801), and was appointed as Academician of the Grand Secretariat. He had a passion for seal-engraving. (The purple clay teapot in hexafoil shape encased in pewter by Zhu Jian (cat no. 48) has an inscription: “Yiyou qiyue Hongfang zhuren ming” [inscribed by Master Hongfang in the seventh month of the yiyou year (1825)]).

14. Xu Lian (1787-1862), zi Shuxia, hao Shanlin, was a native of Hailing, Zhejiang Province. He Passed the jinshi degree in the thirteenth year of the Daoguang reign (1833). He was versed in calligraphy. He died at the age of 76. (The purple clay teapot in hexafoil shape encased in pewter by Zhu Jian (cat. no. 48) has an inscription: “Yuchuan pincha tu, Shanlin” [Tasting tea by the jade stream, Shanlin]).

15. Ye Zheng, zi Hanxian, was a native of Pinghu, Zhejiang province. He was a student of Xu Taizeng, and a proficient landscape painter in ink. He died at the age of 59. (The ink painting of Prunus by Zhu Jian (cat. no. 57) has an inscription: “Daoguang jiyou renxia wei Hanxian sanxiong daya zhishu” [at the refined request of Hanxian in the summer month of the jiyou year in the Daoguang era (1849)]).

16. Cheng Tinglu (1796-1858), original name Zhenlu, zi Yunzhen, Wenchu, hao Luqing. Later he changed his name to Tinglu, zi Xubo, hao Hengxiang. He was a government student in Jiading. Proficient in ci-lyric and essays, he was also an occasional painter and seal engraver. (The fan painting of Fruits and flowers (cat. no. 58) has an inscription: “Daoguang jiachen sanyue Xubo Chengzi guaiguan shuhua shiyuzhong” [Xubo Mr. Cheng brought along over ten pieces of painting and calligraphy for my appreciation in the third month of the jiachen year during the Daoguang era (1844)]).

17. Tao Qi (1814-1865), zi Zhui’an, was a native of Jiaxing, Zhejiang province. He was proficient in painting and poetry, and was the author of Zhongxiaotang ji [Collected Works of Zhongxiaotang]. (The fan painting of Fruits and flowers (cat. no. 58) has an inscription: “Shi Xiushui Taozi Zhui’an yi zaizuo” [at that time Tao Zhui’an of Xiushui was also present]).

18. Gai Oi (1774-1829), hao Qixiang, Yuhu waishi, was a native of Songjiang (present-day Shanghai). His ancestry can be traced to westem China. He was best known for his female figure paintings. (The inkslab engraved with painting and poems for Gai Qi by Zhu Jian (cat. no. 56) has an inscription: “Renwu qiuri Qixiang deyu Qijiang keshe, shu Zhujun Shimei ke yi jixhi” [acquired by the Qijiang Residence of Qixiang in an autumn day in the renwu year (1822), Zhu Jian inscribed it at Qixiang’s request]).

Zhu Jian’s pot designs were very innovative, and he created so many typeforms that no other teapot makers could rival him. Judging from the eight pewter pots by Zhu Jian in this catalogue (cat. nos 46-51), he was a prolific designer, producing unprecedented typeforms such as qin-zither (cat no. 44), measure (cat. no. 45) and melon (cat. no. 46).

Like Shen Cunzhou of the early Qing period, Zhu Jian was a pewter pot maker who engraved his own poetry and seals to decorate the body of the pot. Unlike Shen who was not a painter, Zhu was a proficient painter of prunus, frequently engraving floral designs on teapots (cat no. 44, 49,50, 51) as a personal feature. One exception is the teapot of gourd shape (cat. no. 46), which is not decorated with any painting design. The pewter teapot of conical shape (cat. no. 48) is only decorated by a large rock, while the purple clay teapot of hexafoil shape encased in pewter (cat. no. 47) was incised with the painting, Tea Tasting by the Jade Stream by Xu Lian.

The drawings of Chen Hongshou’s teapots in the Appendix of this catalogue was executed by Zhu Jian. The copy is evidence of Zhu’s interests and studies of the typeforms and styles of the works by past pot masters. The pewter teapots of conical shape engraved with rock decoration (cat. no. 48) and of measure shape (cat. no. 45) by Zhu Jian have the seal “Shimei zuo” [made by Shimel] in clerical script, and inscription of “Pinquan” [grading the stream] in the interior respectively. The pewter octagonal wine ewer of lotus shape by Shen Cunzhou (cat. no. 5) also has a two-character inscription of “Lianquan” in regular script inside. The pewter wine cup by Zhu Jian (cat. no. 52), engraved with a twin-fish design on the interior bears a four-character inscription of “Zuobao zunyi” in seal script in the centre. The inscription reading “Zhuoyi dadou, yiqi huangqi” was engraved in clerical script on the inside of a pewter wine dou-cup by Shen Cunzhou for Zhu Yizun. We can deduce that Zhu Jian assimilated the experiences and techniques of earlier pot masters, developing his own style. Zhu compiled the Hushi [History of Pots],20 which was highly regarded by the literati of his time. Unfortunately this book is no longer extant, and is indeed a great loss to the study of the art of pot-making.

Zhu Jian also copied the purple clay water pot of ancient well shape designed by Chen Hongshou (cat. no. 17), most probably Zhu would have examined the original work. The water pot by Chen Hongshou bears an inscription by Xiquan daoren stating that Chen made a teapot and a water pot after the shape of the ancient well inside the Bao’en Temple outside the East Gate of Liyang. The water pot was dated the sixth month of the bingzi year of Jiaqing era (1816). The teapot is now housed in the Nanjing Museum and measures 5 cm in height and 10.7 cm in diameter. The copy by Zhu is similar in appearance but smaller in size, with a height of 3.8 cm. It has the seal of “Shimei fangji” [copied by Shimei] on the base.21

As mentioned in the Molin Jinhua [Contemporary Remarks on the Ink World], “purple clay pot encased in pewter is his [Zhu Jian] innovation”. Zhu’s pewter pots can be divided into two types; purple clay body encased with pewter and pure pewter. The first type can be found in a number of examples illustrated in this catalogue (cat. nos 44, 47, 50, 51). The second type without purple clay body include cat. nos 45, 46 and 48.

Zhu Jian collaborated with other pot makers as well. One example of his collaboration with Yang Pengnian is the purple clay teapot of bamboo-section shape housed in the collection of the Shanghai Museum and inscribed by him.22 The purple clay teapot of ovoid shape encased in pewter (cat. no. 49) has a seal mark of “Yang Pengnian zhi” [made by Yang Pengnian] stamped on the inside. Another teapot of ovoid shape (cat. no. 51) has a seal mark of “Pan Dahe zhi” [made by Pan Dehe] also stamped on the inside bottom. There is another purple clay bell-shaped pot inscribed by Zhu Jian and made by Shen Xi in the collection of the Nanjing Museum.

Zhu Jian’s calligraphic inscriptions include regular, running, clerical and seal scripts. His signatures include “Shimei”, “Zhu Jian”, “Boyaju”, “Mei daoren”, and “He daoren”. The inside of the pots are found with the seal “Shimei mogu” [Shimei imitating ancient prototype] and the inscriptions “Pinquan [grading the stream]” and “Shimei zuo” [made by Shimei], The seals found on the body of the pots include “Shimei fangzhi” [imitated by Shimei], “Shimei shouzhi” [handmade by Shimei], “Daoguang shiyoujiu nian Shimei jianzao” [supervised manufacture by Shimei in the nineteenth year of the Daoguang reign (1839)], “Shimei mogu” [Shimei imitating ancient prototype], “Shimei zhi” [made by Shimei] and “Lao Mei” [Old man Mei]. His pewter pots were made with handles in different media such as pewter, jade and redwood. His wooden handles were inlaid with silver-thread characters such as “Boyazhai Shimei zhi” [made by Shimei of Boyazhai], “Luyinfang Shimei zhi” [made by Shimei of Luyinfang] and “Hushi” [pot historian].

Zhu also excelled in using different combinations of media in making the cover knobs, spouts and handles of his pots. For the purple clay teapot of qin-zither shape encased in pewter (cat. no. 44), he used a mahogany handle inlaid with silver thread, blue porcelain spout and bronze knob. For the pewter teapot in measure shape (cat. no. 45), he used a jadeite handle, emerald knob and white jade spout. For the pewter teapot in melon shape (cat. no. 46), he used a mahogany handle inlaid with silver thread, and white jade knob. For the purple clay teapot of ovoid shape encased in pewter (cat. no. 49), he used a green jade handle, white jade spout, and emerald knob. For the clay teapot of saucer-lamp shape encased in pewter (cat. no. 50), he used a rmahogany handle inlaid with silver thread, emerald spout, and green jade knob. Zhu Jian’s finest pewter pots are masterpieces of exquisite craftsmanship and his attention to detail exceeds that of Shen Cunzhou.

In the seventh year of the Xianfeng era (1857), when Zhu Jian was aged sixty-eight, it was known that he made a pewter lamp. Throughout his long working life he made large quantities of purple clay and pewter wares. With the outbreak of the Taiping Rebellion, the art of pot-making entered a period of irreversible decline. Zhu Jian became the last master of the literati pot-makers. He revived the making of pewter wares after Shen Cunzhou, and explored novel typeforms, different combinations of materials and more intensive visual quality through the synthesis of painting, calligraphy and seals. He earned the commendation: “full of ingenious ideas” in the Molin Jinhua [Contemporary Remarks on the lnk World].

1 Cha Li (1716-1783), zi Xunshu, Jiantang, hao Congchao, Tieqiao, was a native of Wanping (present-day Beijing). He served as Supervisor of transportation during the Jinchuan campaign in the reign of Emperor Qianlong. Subsequently he rose to the rank of the governor of Hunan province. He died at the age of 68. He was passionate about collecting ancient seals, epigraphy, calligraphy and painting. He modeled his calligraphy after Huang Tingjian (1045-1105), and was proficient in painting landscapes, birds and flowers, in particular prunus. His publications include Tonggu shutang yigao [Posthumous Works of the Tonggu Studio] and Huamei tiba [Colophons on Plum Blossom Paintings].

2 In chapter 6 of Gudong suoji [Ancedotes of Antiques] by Deng Zhicheng (1807-1960), it was mentioned that Cha Li had composed a long ballad praising a reading lamp made by Shen Cunzhou, a gift from Wan Guangtai. The gift of the lamp should predate Wan Guangtai’s death in 1755, most probably after 1736 when Wan was only twenty years old. Assuming Shen Cunzhou and Zhu Yizun were of similar age, and lived just as long, Shen might have died around 1709, similar in age as Zhu. Reckoning in this way, Wan probably presented the lamp to Cha as a gift between thirty to sixty years after Shen’s death. At that time Shen’s pieces were already valuable collectibles worthy as gifts.

3 Wan Guangtai (1717-1755), zi Xunchu, Qingchu, hao Zhepo, was a native of Xiushui (present-day Jiaxing, Zhejiang province). He became a jinshi in 1736 and was appointed Reader. He excelled in poetry, landscape painting and seal- engraving. His extant works include Zhepo shiji [Poetry of Zhepo] and Sun Zizhuang yinpu [Manual of Seal-Engravings by Sun Zizhuang].

4 According to Jiaxing fuji [District History of Jiaxing], Shen was a master pewter-smith. He had studied poetry under Sheng Yuan and was also an accomplished calligrapher.

5 Ibid. “Sheng Yuan, zi Hejiang, was a talented man. He did not pursue the undergraduate studentship at the university of the Qing education system. Instead he travelled extensively and visited the capital three times, making many friends. One of them was Huang Jialin, the provincial governor at Zhiyang. Later, Huang erected a pavilion for Sheng to teach his many students. … His calligraphy followed the style of Dong Qichang (1555-1636). His poems were highly praised and were published in Banxiangge shiji [Collected Works of Poetry from the Banxiang Pavilion].”

6 Being a well-known scholar, Sheng Yuan had made many friends. More than a hundred of them were mentioned in his collected works of poetry known as Banxiang shihui [Collected Works of Poetry by Banxiang]. Among them are Ku Liangfen (1637-1714), Cha Shengshan (1650-1707), Chen Qinian (1625-1682) and Zhu Yizun (1629-1709).

7 According to Naileng tan, “ … Shen wrote a poem and engraved it on the side of the dou-cup as a birthday gift to Zhu Yizun. On the inside, Shen also inscribed eight characters in clerical script reading, ‘Zhuo yi dadou, Yi qi huangqi’ [Drink from the big pot, and to your long life] followed by a seven-syllabled quatrain.”

8 Ibid. “I had previously read the poems of the Tuoshi Studio, there was a poem regarding Shen Cunzhou’s pewter cup. The poem was written by an official known as Mr Dai. He wrote: ‘Only a square vessel but the wine is plenty; around in a circle, Du Fu’s Song of the Eight Immortals.’ Inscribed in the gengxu year under the reign of Kangxi (1670). At that time, I was only eleven years old. Qian Zai composed the poem sixty to seventy years after the production of the cup. By then it was already highly treasured, and today it is even rarer.”

9 According to Jiaxing fuji [District History of Jiaxing], “Shen was a master pewter-smith who was known for making fine pewter wares. Pots in monk’s cap shape were his best. Those in lotus and walnut shapes were second best. His engraving of verses, names, pictures and seals on the teapots was unsurpassed even by skilled carvers of his time.”

10 Similar biographical details of Qu Yingshao are found in Qingdail huashi zenbian [Supplement to the History of Painting of the Qing dynasty], Qing huajia shishi [History of Poetry by Painters of the Qing Period] and chapter four of Ouboluoshi shuhua guomukao [Study on Viewed Paintings and Calligraphy of Ouboluoshi].

11 Zhang Dan, zi Gengyun, Xinzhi, hao Chunshui, was a native of Wuxian, Jiangsu province. He was passionate about painting and was taught by Qian Zhiwei. He visited Wuling (present day Hangzhou) and befriended Ma Lutai and Tu Zhuo. Later he became an adviser to Tang Yifen. For the latter part of his life, he settled in Shanghai. He was also a skilled seal carver. In his preface, Zhang Dan stated that Qu was a scholar from an illustrious family in Shanghai. For generations, members of his family were graduates with degrees from the civil service examination and also men of letters.

12 Liu Shu, zi Hongfu; biography unknown. In his preface, Liu Shu wrote of Qu Yingshao: “Before he was thirty, Ziye’s poems were full of literary elegance; after forty his poems were imbued with robustness through age.”

13 Xu Weiren (?-1853), zi Wentai, hao Zishan, Suixuan, was a native of Shanghai. He was both a connoisseur and collector. He made friends with Liang Tongshu, Chen Mansheng, Zhang Tingji, and Wang Xuehao and formed a study group for calligraphy, painting, and epigraphy. He was a proficient calligrapher, well versed in seal, clerical, running and regular scripts. He began painting orchid and bamboo at the age of thirty-eight. Later he also painted landscapes.

14 Mo Shuyu, zi Zaitian, hao Yuntan, was a Shanghai scholar in the reign of Daoguang. He excelled in calligraphy after the style of Ouyang Xun and Chu Suiliang of the Tang dynasty.

15 The battle at Wusong occurred in the renyin year during the Opium War. Opium was imported through the East India Company to Guangzhou by British merchants. In 1839 Emperor Daoguang sent Commissioner Lin Xexu to Guangxhou to stamp out the trade. In 1840 with the support of USA and France, the British waged war on China, and its fleet began to blockade all Chinese ports. Finally in the spring of 1842 Sir Henry Pottinger led the British forces up the Yangtze River taking strategic cities: Wusong on 16 June, Jinjiang on 21 July and threatening Nanjing. In August, the Chinese government was forced to acquiesce to all British demands and signed the Treaty of Nanjing ceding Hong Kong island to the British. Qu Yingshao’s manuscripts of poems were lost when Qu’s family fled the battle at Wusong.

16 Refer to Yixing zisho zhenshang [Appreciation of Purple Clay Wares of Yixing], p.114, plate 107; p.120, plate 109 and p.121, plate 110.

17 The Art of the Yixing Potter: The K.S. Lo Collection, Flagstaff House Museum of Tea Ware, p.170, cat. no.57.

18 Both the Molin jinhua [Contemporary Remarks on the Ink World] and Quboluoshi shuhua guomu kao [Study on Viewed Paintings and Calligraphy of Ouboluoshi] gave similar biographical accounts of Zhu Jian. In addition, they attributed Zhu as the author of Hushi [History of Teapots] and an expert seal engraver.

19 K.S. Lo Collection in the Flagstaff House Museum of Tea Ware Part 2, p.73, cat. no.45.

20 Molin jinhua [Contemporary Remarks on the Ink World] mentioned that Zhu “was the author of one volume of Hushi, which was inscribed and recited by many scholars since the Jiaqing and Daoguang reigns.”

21 Refer to Yixing zishao zhenshang [Appreciation of Purple Clay Wares of Yixing], p.114, plate 102 left.

22 Ibid. , p. 111, plate 097.

%MCEPASTEBIN%