理雅各 (James Legge 一八一五至一八九七) 為晚清英譯吾國經籍巨擘,西學風靡之際,獨譯東學披世。同治六年 (一八六七),知交王韜撰「送西儒理雅各回國序」,曰:

「嘉慶年間,始有名望之儒至粵,曰馬禮遜 (Robert Morrison 一七八二至一八三四),繼之者曰米憐維琳 (William Milne 一七八五至一八二二),而理君雅各先生亦偕麥都思 (Walter Henry Medhurst 一七九六至一八五七) 諸名宿橐筆東游。先生於諸西儒中年最少,學識品詣卓然異人。和約既定,貨琛雲集,中西合好,光氣大開,泰西各儒,無不延攬名流,留心典籍。如慕維廉 (William Muirhead 一八二二至一九零零),禆治文之地志,艾約瑟(Joseph Edkins 一八二三至一九零五) 之重學,偉烈亞力 (Alexander Wylie 一八一五至一八八七) 之天算,合信氏 (Benjamin Hobson 一八一六至一八七三) 之醫學,瑪高溫 (Daniel Jerome Macgowan 一八一四至一八九三) 之電氣學,丁韙良 (William Alexander Parsons Martin 一八二七至一九一六) 之律學,後先並出,競美一時。然此特通西學於中國,而未及以中國經籍之精微通之於西國也。先生獨不憚其難,注全力於十三經,貫串攷核,討流溯源,別具見解,不隨凡俗。其言經也,不主一家,不專一說,博采旁涉,務極其通,大抵取材於孔、鄭而折衷於程、朱,於漢、宋之學兩無偏袒,譯有 『四子書』、『尚書』 兩種。書出,西儒見之,咸歎其詳明該治,奉為南鍼。」

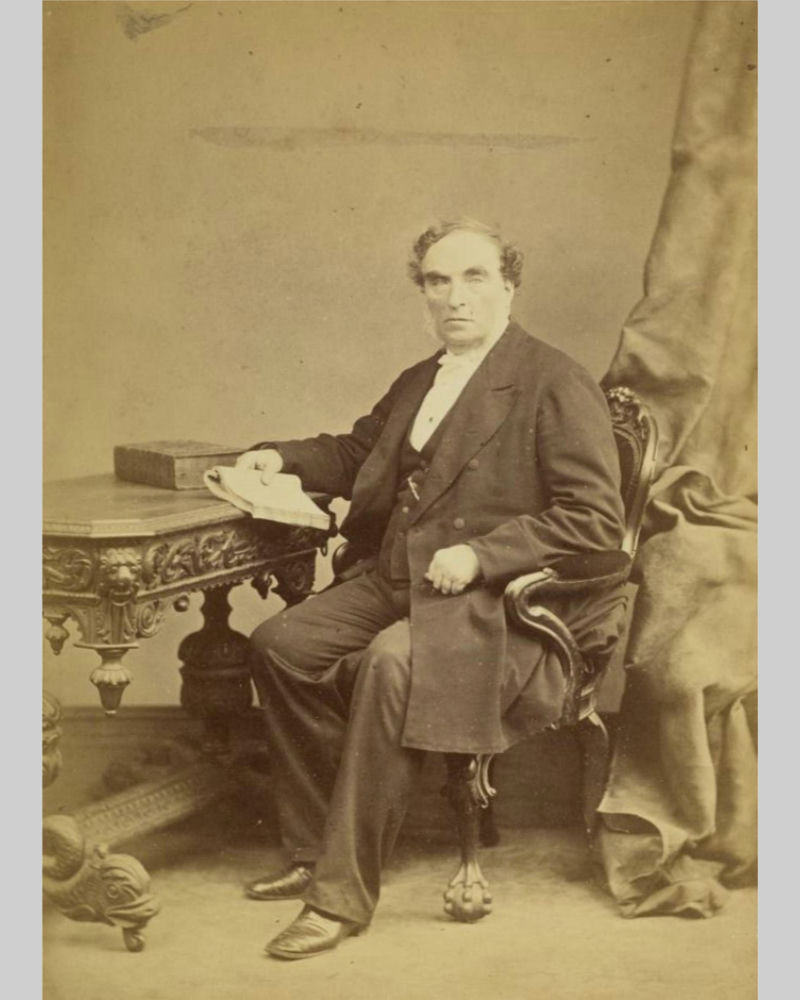

理雅各教授肖像,牛津大學珍藏。圖片來源: Bridgeman Images

理雅各,英國蘇格蘭亞伯丁 (Aberdeenshire) 人。畢業倫敦海布里神學院 (Highbury Theological College),一八三九年赴中國傳教。途經馬六甲,授任英華書院 (Anglo-Chinese College) 校長,一八四四年隨校遷徙香港,續任校長職至一八六七年,合二十四年,兼任香港佑寧堂 (Union Church) 牧師,其間嘗於一八四六年返英年餘。一八六二年十月,王韜避難香港,交理雅各,協襄翻譯,遂成莫逆。一八六七年,理雅各返英,邀王韜同行。一八七零年至一八七三年,復職香港佑寧堂牧師。一八七三年遍遊大陸各地勝跡,歲末返英。一八七五年受薦為牛津大學柯泊史克利斯特學人 (Fellow of Corpus Christi College),翌年任牛津大學首任漢學教授 (Chair of Chinese Language and Literature)。據載當時弟子僅數人,理雅各每日清晨三時起,一盞桌燈,一杯熱茶,伏案徹夜翻譯經籍,至夜晚十時寢,不分寒暑,如此者二十餘年。著有 「陝西西安府大秦景教流行中國碑」 The Nestorian Monument of Hsi-an fu in Shen-hsi、「中國之宗教-以儒教與道教陳述比擬基督教」 The Religions of China, Confucianism and Taoism described and compared with Christianity、「孔子生平與學說」 The Life and Teachings of Confucius、「孟子生平與學說」 Life and Works of Mencius。翻譯有 「中國經典」 The Chinese Classics、「中國之聖書-道教文獻」 The Sacred Books of China, the Texts of Taoism。

寒齋珍藏理雅各致肖林 (William Sheowring) 英文信箋兩通。

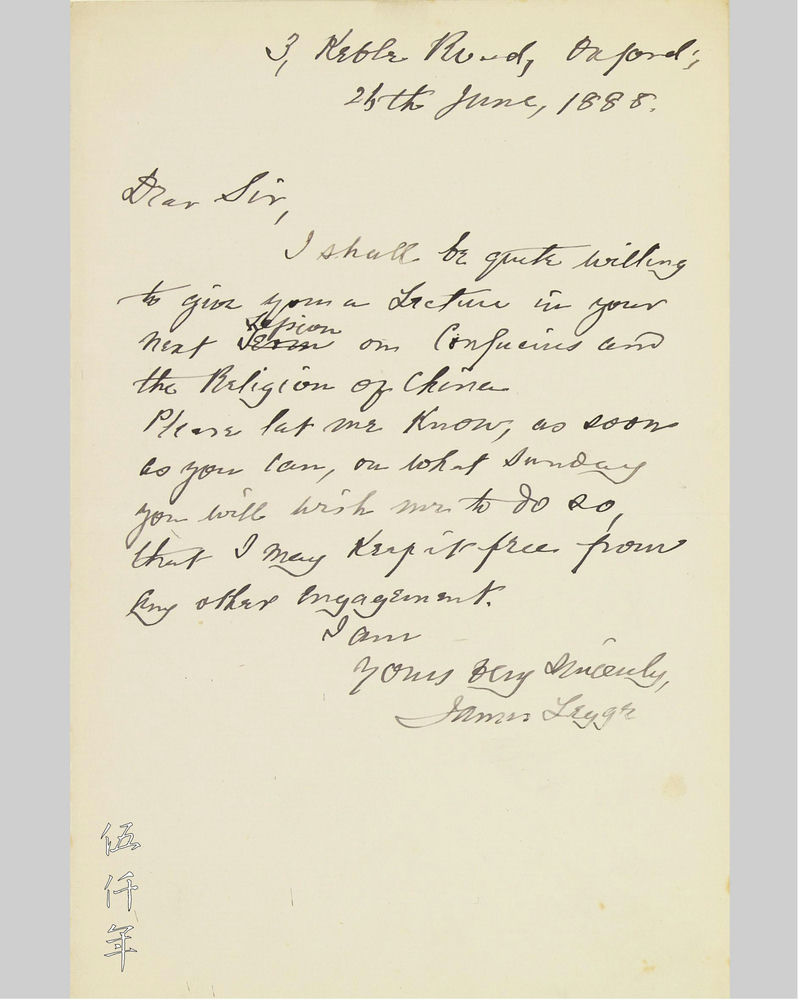

一八八八年理雅各致肖林信箋。賦梅花館藏

首通:一八八八年六月二十六日書於牛津。

信云:

“3, Keble Road, Oxford,

26th June, 1888.

Dear Sir,

I shall be quite willing

to give you a Lecture in your

next session on Confucius and

the Religion of China.

Please let me know, as soon

as you can, on what Sunday

you will wish me to do so,

that I may keep it free from

any other engagement.

I am

Yours very sincerely,

James Legge”

譯文:

「余欣願於下回 貴社聚會,作『孔子與中國宗教』演講。星期天之演講,汝冀定何日,盼速惠告,當即擱留是日,不謀他事。」

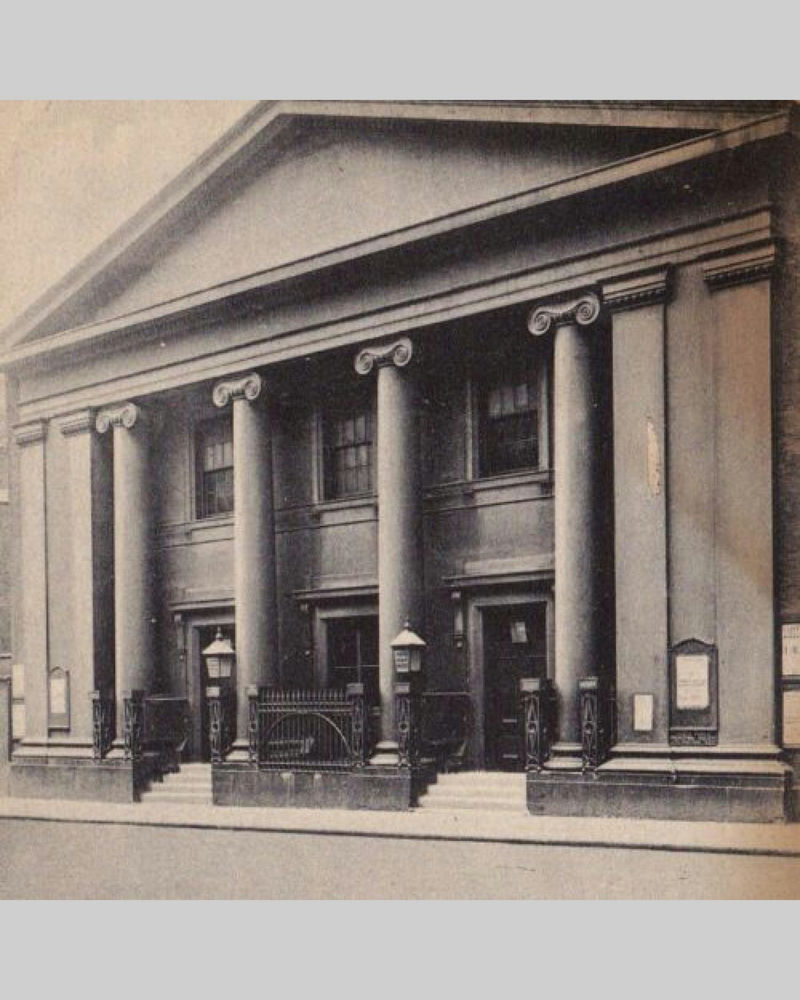

一八八八年,理雅各於英國倫敦芬斯伯里區南地道德學會演講,其建築外景。圖片來源: Conway Hall Collection

一八八八年,理雅各年七十四,業任牛津大學漢學教授職十三年。信未具名,實致肖林 (William Sheowring),首通當與次通共讀。肖林乃南地道德學會 (South Place Ethical Society) 秘書,是信回覆邀請演講事。理雅各信中擬訂之倫敦演講題目名「孔子與中國宗教」。

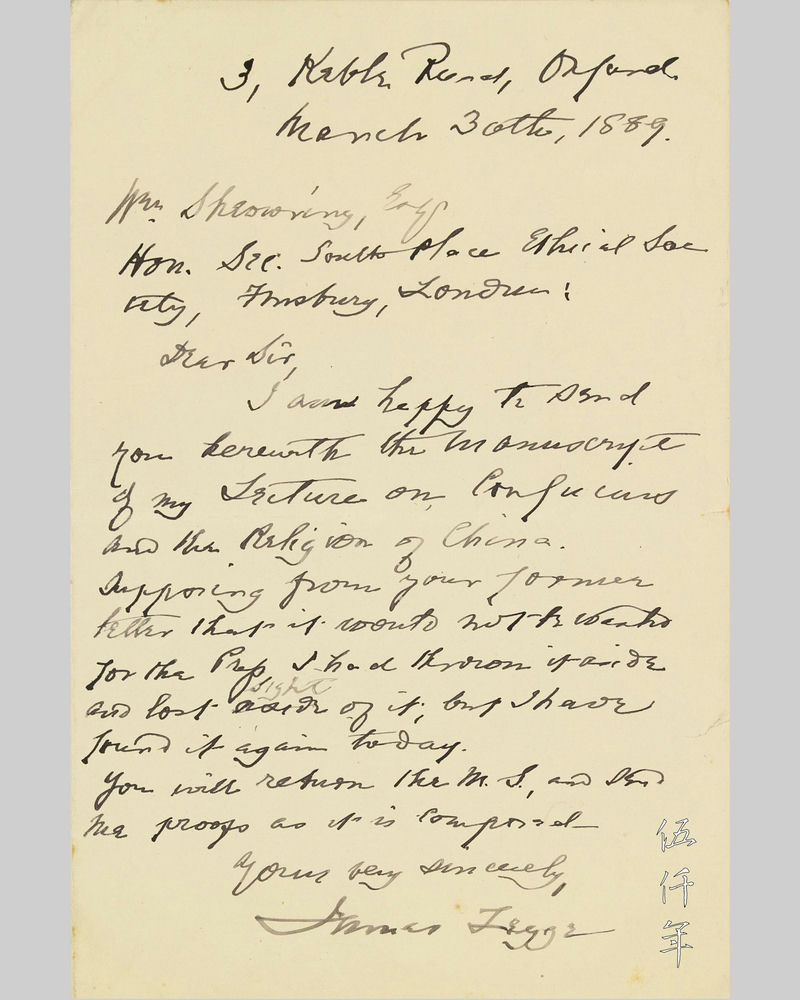

一八八九年理雅各致肖林信箋。賦梅花館藏

次通:一八八九年三月三十日書於牛津

信云:

“3, Keble Road, Oxford.

March 30th, 1889.

Mr. Sheowring, Esq.

Hon. Sec. South Place Ethical Soc-

iety, Finsbury, London.

Dear Sir,

I am happy to send

you herewith the manuscript

of my Lecture on Confucius

and the Religion of China.

Supposing from your former

letter that it would not be wanted

for the Press, I had thrown it aside

and lost sight of it, but I have

found it again today.

You will return the M.S., and send

me proofs as it is composed.

Yours very sincerely,

James Legge”

譯文:

「余欣寄『孔子與中國宗教』講辭手稿。前函意謂講稿不作印刷之用,固擲於一旁,不知所終,今始尋獲。務請歸還原稿, 並寄印刷校樣。」

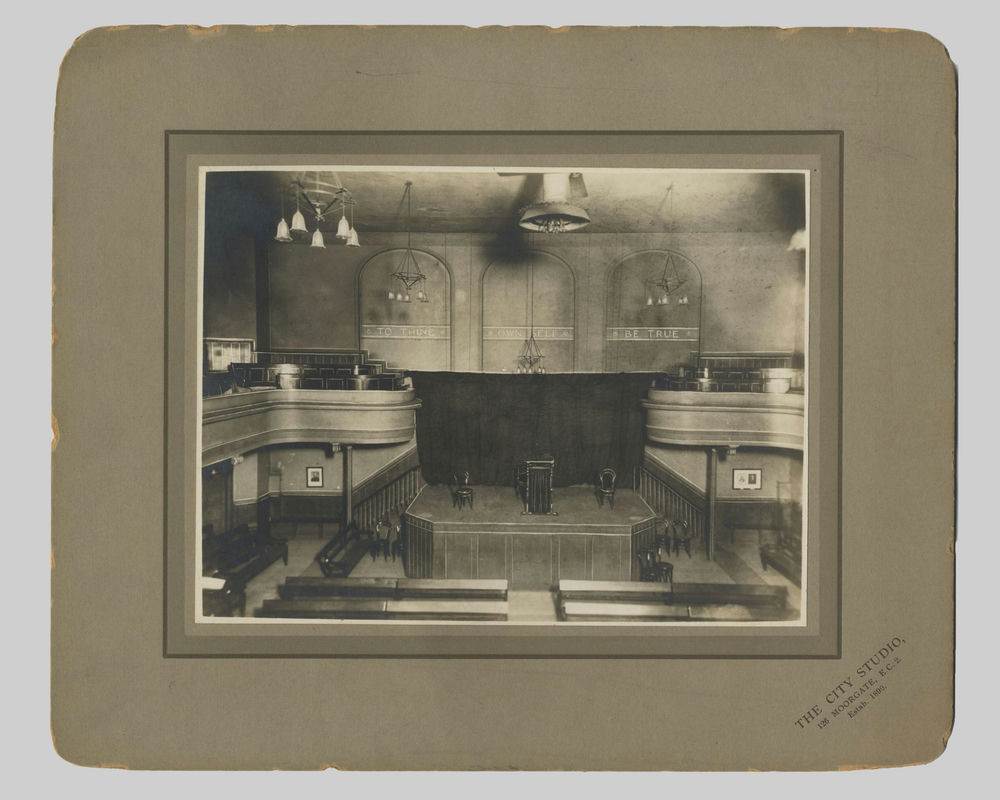

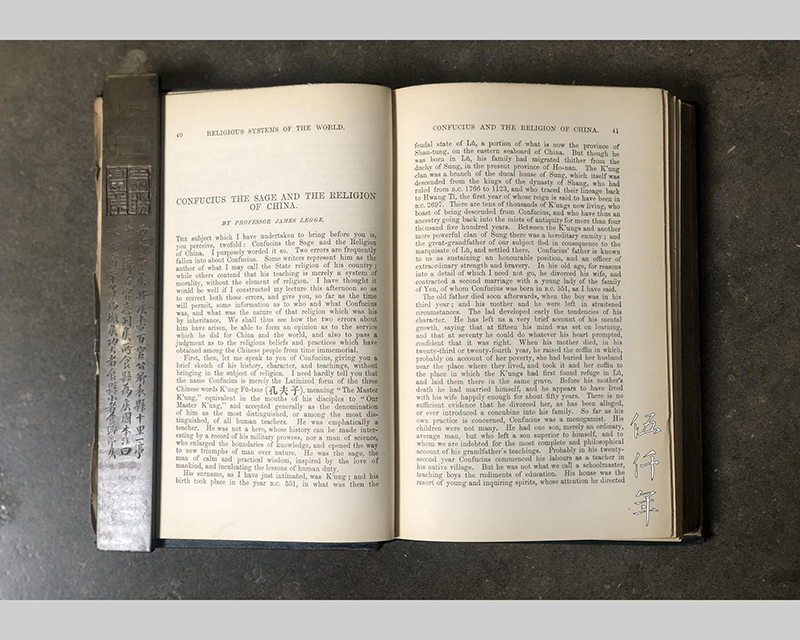

一八八八年,理雅各於英國倫敦芬斯伯里區南地道德學會演講,其建築室內撮影。圖片來源: Humanist Heritage

一八八八年六月後,理雅各赴倫敦芬斯伯里區南地道德學會演講。翌年,秘書肖林擬裒集一八八八年至一八九八年間,曾於南地道德學會演講之四十學人演講辭稿,編纂成書,名 「世界宗教系統–國族系統、基督教系統、哲學系統。一八八八至一八八九南地學院各家講辭集錦。」 Religeous Systems of the World. National, Christian, and Philosopic. A Collection of addresses delivered at South Place Institute in 1888-1889. 是書一八九零年出版,共刊載四十篇講辭,排序四即理雅各之講辭,其題目於演講前修改為 「先聖孔子與中國宗教」,與信中所擬題目略異,增 「先聖」 兩字。英文講辭全篇錄於文後,以饗同好。

南地道德學會原名南地宗教學會 (South Place Religeous Society),肇創於一七八七年,一八八八年易名,原址倫敦芬斯伯里區南地教堂 (South Place Chapel)。南地道德學會為西方最早成立持奉自由思想主義之民間團體。

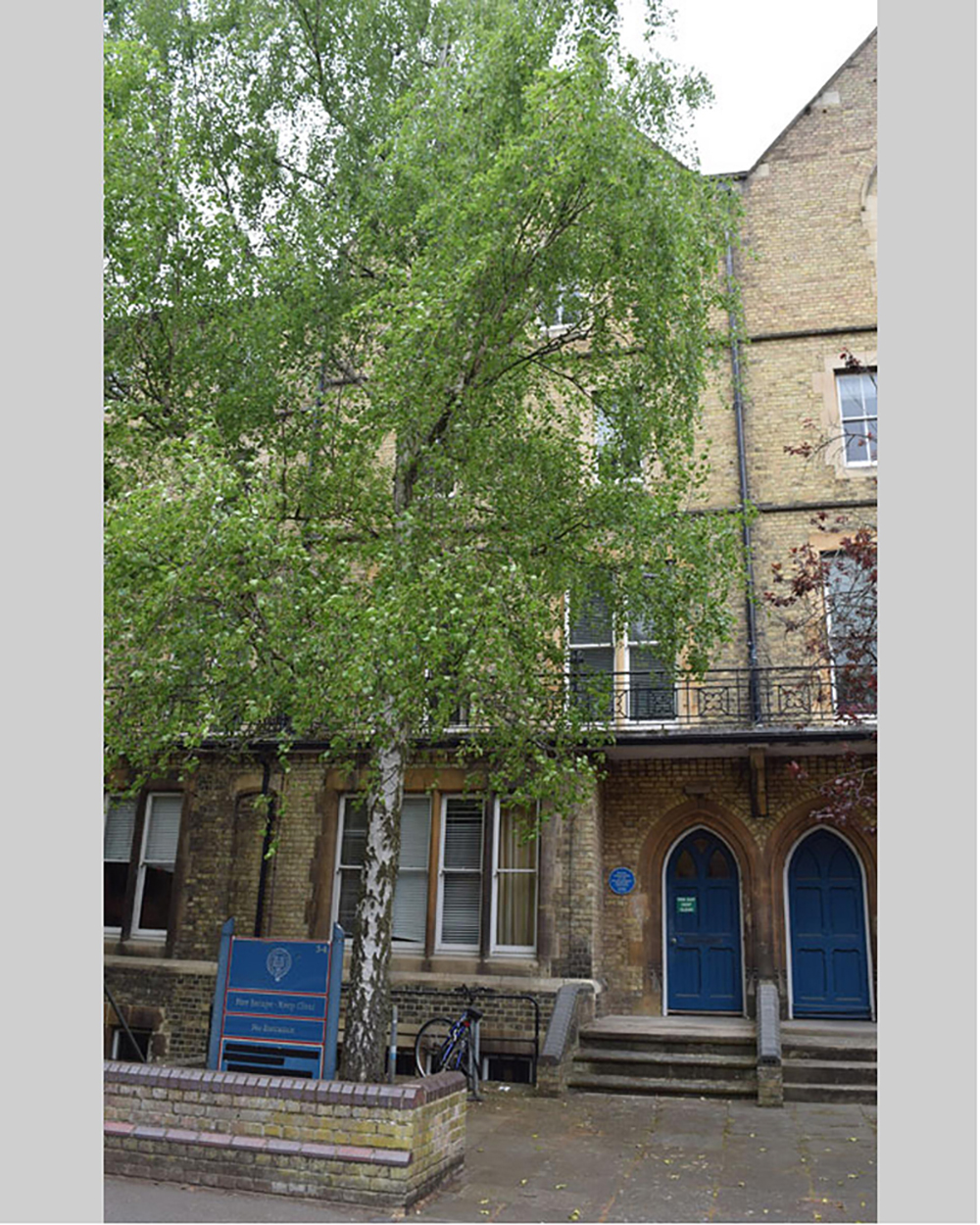

英國牛津市基布爾路三號理雅各故居外景。圖片來源: 牛津郡藍牌管理處

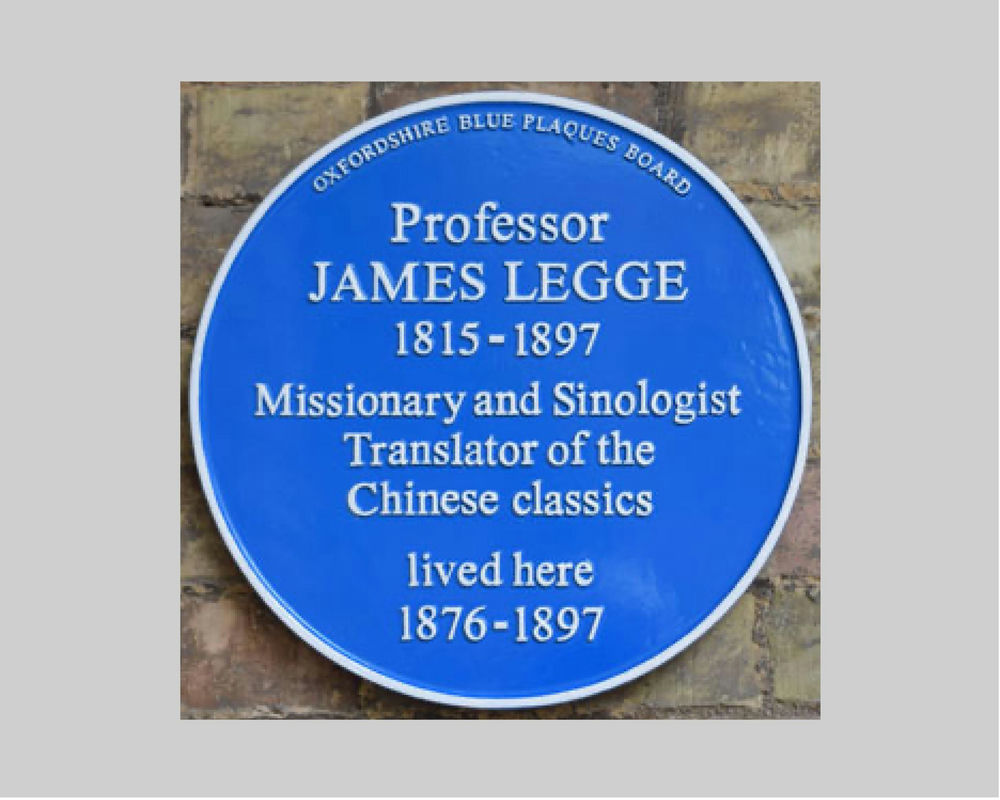

英國牛津市基布爾路三號理雅各故居外牆紀念牌。圖片來源: 牛津郡藍牌管理處

信箋上方所書地址為牛津市基布爾路 (Keble Road) 三號,於今猶存。理雅各自一八七五年遷抵牛津,至一八九七年逝世,寓居此棟四層樓房二十三年。二零一八年,當地政府於建築外牆,增置一圓形名人故居銅牌,以茲紀念導航東學西漸之一代學人。

理雅各演講 「先聖孔子與中國宗教」,輯入肖林裒集之 「世界宗教系統–國族系統、基督教系統、哲學系統。一八八八至一八八九南地學院各家講辭集錦。」

CONFUCIUS THE SAGE AND THE RELIGION OF CHINA.

BY PROFESSOR JAMES LEGGE.

THE subject which I have undertaken to bring before you is, you perceive, twofold: Confucius the Sage and the Religion of China. I purposely worded it so. Two errors are frequently fallen into about Confucius. Some writers represent him as the author of what I may call the State religion of his country; while others contend that his teaching is merely a system of morality, without the element of religion. I have thought it would be well if I constructed my lecture this afternoon so as to correct both those errors, and give you, so far as the time will permit, some information as to who and what Confucius was, and what was the nature of that religion which was his by inheritance. We shall thus see how the two errors about him have arisen, be able to form an opinion as to the service which he did for China and the world, and also to pass a judgment as to the religious beliefs and practices which have obtained among the Chinese people from time immemorial.

First, then, let me speak to you of Confucius, giving you a brief sketch of his history, character, and teachings, without bringing in the subject of religion. I need hardly tell you that the name Confucius is merely the Latinized form of the three Chinese words K’ung Fû-tsze (孔夫子), meaning “The Master K’ung,” equivalent in the mouths of his disciples to “Our Master K’ung,” and accepted generally as the denomination of him as the most distinguished, or among the most distinguished, of all human teachers. He was emphatically a teacher. He was not a hero, whose history can be made interesting by a record of his military prowess, nor a man of science, who enlarged the boundaries of knowledge, and opened the way to new triumphs of man over nature. He was the sage, the man of calm and practical wisdom, inspired by the love of mankind, and inculcating the lessons of human duty.

His surname, as I have just intimated, was K’ung; and his birth took place in the year B.C. 551, in what was then the feudal state of Lû, a portion of what is now the province of Shan-tung, on the eastern seaboard of China. But though he was born in Lû, his family had migrated thither from the duchy of Sung, in the present province of Ho-nan. The K’ung clan was a branch of the ducal house of Sung, which itself was descended from the kings of the dynasty of Shang, who had ruled from B.C. 1766 to 1123, and who traced their lineage back to Hwang Tî, the first year of whose reign is said to have been in B.C. 2697. There are tens of thousands of K’ungs now living, who boast of being descended from Confucius, and who have thus an ancestry going back into the mists of antiquity for more than four thousand five hundred years. Between the K’ungs and another more powerful clan of Sung there was a hereditary enmity; and the great-grandfather of our subject fled in consequence to the marquisate of Lû, and settled there. Confucius’ father is known to us as sustaining an honourable position, and an officer of extraordinary strength and bravery. In his old age, for reasons into a detail of which I need not go, he divorced his wife, and contracted a second marriage with a young lady of the family of Yen, of whom Confucius was born in B.C. 551, as I have said.

The old father died soon afterwards, when the boy was in his third year; and his mother and he were left in straitened circumstances. The lad developed early the tendencies of his character. He has left us a very brief account of his mental growth, saying that at fifteen his mind was set on learning, and that at seventy he could do whatever his heart prompted, confident that it was right. When his mother died, in his twenty-third or twenty-fourth year, he raised the coffin in which, probably on account of her poverty, she had buried her husband near the place where they lived, and took it and her coffin to the place in which the K’ungs had first found refuge in Lû, and laid them there in the same grave. Before his mother’s death he had married himself, and he appears to have lived with his wife happily enough for about fifty years. There is no sufficient evidence that he divorced her, as has been alleged, or ever introduced a concubine into his family. So far as his own practice is concerned, Confucius was a monogamist. His children were not many. He had one son, merely an ordinary, average man, but who left a son superior to himself, and to whom we are indebted for the most complete and philosophical account of his grandfather’s teachings. Probably in his twenty-second year Confucius commenced his labours as a teacher in his native village. But he was not what we call a schoolmaster, teaching boys the rudiments of education. His house was the resort of young and inquiring spirits, whose attention he directed to the ancient monuments of the nation’s history and literature, unfolding to them at the same time the principles of human duty and of government. This was the work of his life. His disciples, first and last, amounted, it is said, to three thousand; and among them there were between seventy and eighty whom he highly valued, and praised as “scholars of extraordinary ability.” From the time that he thus comes before us on the stage of public life, and especially during the long period of wandering among different states that subsequently befell him, he always appears attended by companies of his disciples. These must have supported him. In his earlier school he received all who came to him for instruction, and did not refuse the smallest fee; but he required from all an ardent desire for improvement and a good measure of capacity. It is difficult for us, however, to understand this feature of his course: how, while dependent on the sympathy and support of his followers, he yet maintained among them the most entire authority and independence. When Mencius, who is styled “a secondary Sage,” came after him, about a century and a half later, and went about the country in the same way, enforcing the lessons of “the Master,” he accepted the gifts of different princes to an extent that startled even his disciples. But Confucius never did so. He would not demean himself to receive help from a ruler whom he disapproved, and who would not carry out his principles in the government of his people. Confucius must have been supported by the free-will contributions of his disciples. This point in the study of his course has often suggested to me the passage in the Gospel of Luke where it says (chap.viii.1-3) that Jesus “went about through cities and villages, preaching the good tidings of the kingdom of God, and with Him the twelve and certain women that had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities: Mary Magdalene and Joanna, the wife of Chuza, Herod’s steward and Susanna, and many others, which ministered to them of their substance.”

A noble by descent, and soon widely known for his attainments, Confucius might have expected to be called to a position in the government of the State. But the time was one of great corruption and disorder. The general government of the kingdom was feeble, and every feudal state was torn by contentions between its ruler and the Heads of the clans in it, as well as by collisions between those clans themselves. It was not till he was over fifty that Confucius was made governor of one of the towns of Lû. There his administration was so successful that he was soon raised to higher dignities, and at last became Minister of Crime for the whole State. “He strengthened,” we are told, “the ruling house, and weakened the usurping chiefs. A transforming government went abroad. Dishonesty and dissoluteness were ashamed, and hid their heads. Loyalty and good faith became the characteristics of the men, and chastity and docility those of the women. Confucius became the idol of the people, and flew in songs through their mouths. The people of other states flocked in crowds to Lû, to enjoy the blessing of its good order.” But this sky of bright promise was soon overcast. The other states became jealous of the prosperity of Lû, and afraid of the influence of its Minister of Crime. The Marquis of Ch’î, the nearest of them, succeeded, by a most scandalous scheme, in alienating the mind of the ruler of Lû from his wise counsellor. Confucius became convinced that it was unbecoming his character to continue longer in the State. Slowly and sorrowfully he left it, and in B.C. 496 went forth, with a company of his disciples, to thirteen years of homeless wandering, trying to find a ruler who had ears to hear his instructions and goodness and wisdom to follow them. The quest was in vain, but the record of his experiences during that long and painful time is full of interest.

More than once he and the faithful few who would not leave him were in danger of perishing from want, or at the hands of excited mobs. On one occasion, when they were surrounded by an infuriate multitude and the disciples were alarmed, he calmly said to them, “Heaven produced the virtue that is in me. What can these people do to me?” This was always the way in which Confucius spoke in his highest utterances about himself. He never claimed to be anything more than man; but he felt that he had a divine mission. He knew the Way;- the way for the individual to perfect himself and the way for governors to rule so as to make their people happy and good. To teach this was his mission, and he would be faithful to it to the last. In the midst of his disciples, famishing and frightened, he was always calm, and cheered them, singing to his lute.

The wanderers occasionally came across recluses, men who had withdrawn from the world in disgust, and derided him, always striving, and striving in vain, with his plans of reformation. “Than follow one who withdraws from this ruler and that, had you not better follow those who withdraw from the world altogether?” said one of those recluses to a disciple. When his words were reported to the master, he said, “It is impossible to associate with birds and beasts. If I associate not with the people, with whom shall I associate? If the right way prevailed in the world, there would be no need for me to change its state.”

At length Confucius was recalled to Lû in B.C. 483, but he was now in his sixty-ninth year. Only five years more remained to him. He hardly re-entered public life, but devoted the time to completing his literary tasks. His son died in 482, but he bore that event with more equanimity than he did the death of his favourite disciple in the year following. His own death took place in the spring of 478. The account which we have of it is the following:- Early one morning he got up; and with his hands behind him, and trailing his staff, he moved about by the door, crooning over-

“The great mountain must crumble,

The strong beam must break,

And the wise man wither away like a plant.”

After a little he entered the house, and sat down opposite the door. The disciple Tsze-kung, who was in attendance on him, had heard the words, and said to himself, “I am afraid the master is going to be ill.” With this he hastened into the house, when Confucius told him a dream which he had had in the night, and which he thought presaged his death, adding, “No intelligent monarch arises; there is no ruler in the kingdom who will make me his master; my time has come to die.” So it was. He took to his couch, and after seven days expired.

Such was the death of the great sage of China. His end was not unimpressive, but it was melancholy. He uttered no prayer, and he betrayed no apprehension. “The mountain falling came to nought, and the rock was removed out of its place. So death prevailed against him, and he passed. His countenance was changed, and he was sent away.”

I have thus given you a very condensed outline of the events of Confucius’ life. Of his personal appearance, his habits, and his sayings we have abundant details in the records of his disciples. He was tall, and methodical, doing everything in the propre way, time, and place. He was nice in his eating, but not a great eater. He was not a total abstainer from spirituous drink, but he never took too much. To confine myself to what they tell us of him as a teacher:- They found him free from foregone conclusions, arbitrary determinations, obstinacy, and egoism; he would not talk with them about extraordinary things, feats of strength, rebellious disorder, and spiritual beings; he frequently discoursed to them about the books of poetry and history and the rules of propriety; there were three things, he said, in which the greatest caution was required : fasting (as preparatory to sacrifice), going to war, and the treatment of disease; he insisted on their cultivating letters, ethics, leal–heartedness, and truhfulness; and there were three things on which he seldom dwelt: the profitable, the decrees of Heaven, and perfect virtue.

He held that society was made up of five relationships: those of husband and wife, of parent and child, of elder and younger brother or generally of elders and youngers, of ruler and minister or subject, and of friend and friend. A country would be well governed when all the parties in those relationships performed their parts aright, though I must think that he allowed too much to the authority of the higher party in each of them. I do not mean to say that there was no such moral teaching in the literature of China before his time. There was much, but he invested it all with a new grace and dignity. His greatest achievement, however, in his moral teaching was his inculcation of the Golden Rule, which he delivered at least five separate times. Tsze-kung once asked him whether there were any one word which might serve as a rule of practice for all one’s life. His reply was, “Is there not shû?” that is, reciprocity, or altruism; and he added the explanation of it: “What you do not want done to yourself, do not do to others.” The same disciple on another occasion saying that he observed the rule, Confucius simply remarked, “Ah! you have not attained to that!” He tells us, indeed, in one important passage-and we do not think the worse of him for the acknowledgment-that he was not able himself to follow the rule in its positive form in any one of the relationships.

Many of his short sayings are admirable in their pith and sagacity. What could be better than these?-

“Learning without thought is labour lost; thought without learning is perilous.”

“It is only the truly virtuous who can love or hate others.”

“Can there be love which does not lead to strictness in the training of its object? Can there be loyalty which does not lead to the instruction of its object?”

“To be poor without murmuring is difficult; to be rich without being proud is easy.”

There was nothing he liked to set forth more than the character of his superior or ideal man. I will give you one specimen, and only one: “The scholar considers leal-heartedness and good faith to be his coat of mail and helmet, propriety and righteousness to be his shield and buckler; he walks along bearing over his head benevolence; he dwells holding righteousness in his arms before him; the government may be violently oppressive, but he does not change his course: such is the way in which he maintains himself.”

It may occur to you that, notwithstanding all I have said, Confucius does not appear to you in any other character but as an ethical teacher of great merit; but I did not wish in this part of the lecture to exhibit him in any other. Wherein we must attach to his teachings a religious sanction will be seen in the other part to which I will immediately proceed.

Certain failures in his character and writings, moreover, have been pointed out, and by no one so much as myself. He enunciated, for instance, as we have seen, the Golden Rule; but he did not, or would not, appreciate the still higher rule, when his attention was called to it, that good should be returned for evil, and that the evil will thereby be overcome. While he taught truthfulness, moreover, there are many passages in the Spring and Autumn which he claimed especially as his own work, that awaken doubts as to its historical veracity. But, after all, these charges are not very heavy; and he would have recked little of them himself. When he was once charged with slighting an important rule of propriety, all that he said in reply was,“I am fortunate. If I have any errors, people are sure to know them.” You will not be sorry to hear the magnificent eulogium which his grandson pronounced on the ideal sage and king, being understood to have had Confucius in his mind:-

“Possessed of all sagely qualities, showing himself quick in apprehension, clear in discernment, of far-reaching intelligence and all-embracing knowledge, he was fitted to exercise rule; magnanimous, generous, benign, and mild, fitted to exercise forbearance; impulsive, energetic, firm, and enduring, fitted to maintain a strong hold; self-adjusted, grave, never swerving from the mean, and correct, fitted to command reverence; accomplished, distinctive, concentrative, and searching, fitted to exercise discrimination. Therefore his fame overspreads the Middle Kingdom, and extends to all barbarous tribes. Wherever ships and carriages reach, wherever the strength of man penetrates, wherever the heaven overshadows and the earth sustains, wherever the sun and moon shine, wherever frosts and dews fall, all who have blood and breath unfeignedly honour and love him.”

Secondly, let me pass on now to consider what is the nature of the religion of China, what it was in the very earliest times, and what it continues substantially to be at the present day. As we succeed in the study and exhibition of this, we shall discover more clearly the deep foundation of the moral teaching of Confucius, and wherein the religion itself fails to supply to the Chinese people all that is necessary for the nourishment of their spiritual being and the making of them what they ought to be.

There have been from time immemorial two sacrificial services in China: one addressed to the supreme Being and the other to the spirits of the dead. I call them sacrificial services in accordance with the general usage of writers on the subject; but we must not import into the words sacrifice and sacrificial all the ideas which we attach to them. The most common term for sacrifice in Chinese is tsî (祭), and the most general idea symbolized by it is an offering whereby communication and communion with spiritual beings are effected. The offerings, we are told, and the language employed in presenting them, were for the purpose of prayer, or of thanksgiving, or of deprecation. Our meaning of substitution and propitiation does not enter into the term, excepting in the sense of making propitious and friendly.

I will speak first of the former service.

The earliest name for the supreme Being among the Chinese fathers appears to have been Tʼien, or “Heaven.” When the framers of their characters made one to denote “Heaven” (天), they fashioned it from two already existing characters, representing “one” (一) and “great” (大), signifying the vast and bright firmament, overspreading and embracing all, and from which came the light, heat, and rain which rendered the earth beneath fruitful and available for the support and dwelling of man and all other living beings on its surface. But their minds did not rest in the material, or I might almost say the immaterial, sky. The name soon became symbolical to them of a Power and Ruler, a spiritual Being, whom they denominated Tî (帝), “God,” and Shang Tî (上帝), “the supreme God.” I cannot render these terms in English in any other way. The Chinese dictionaries tell us that Tî represents the ideas of lordship and rule.

So it was that the name for the sky which they beheld became to the earliest Chinese personal as the denomination of their concept of God. The same process of thought must have taken place among our own Early Fathers, though the personal name has displaced the material and symbolical term among us much more than it has among the Chinese. The name Heaven for God, however, has not altogether disappeared from our common speech. Witness such phrases as “Heaven knows,” “Please Heaven.” I find the same significance in the words of Daniel to the Babylonian Nebuchadnezzar, “Thou shalt know that the heavens do rule,” and in the penitent language of the returning prodigal, “Father, I have sinned against Heaven and in thy sight.”

The worship of God was associated with a worship of the more prominent objects of nature, such as heaven and earth, the sun and moon, the starry host, hills and streams, forests and valleys. It has been contended from this that the most ancient religion of the Chinese was a worship of the objects of nature. I do not think it was so, and I am supported in my opinion by the express testimony of Confucius that “by the ceremonies of the sacrifices to heaven and earth they served God.” The words supply an instance of his unfrequent use of the personal name, which he employed, I suppose, to give greater emphasis to his declaration. If it was so in the worship of those greatest objects of nature, much more must it have been so in that of the inferior objects. Even though the presidency of those objects may be ignorantly and superstitiously assigned to different spiritual beings, the prayers to them show that the worship of them is still a service of God. In a prayer, for instance, to the Cloud-master, the Rain-master, the Lord of the Winds, and the Thunder-master, it is said, “It is yours, O spirits, to superintend the clouds and the rain, and to raise and send abroad the winds, as ministers assisting the supreme God.” To the spirits of all the hills and rivers under the sky, again, it is said, “It is yours, O Spirits, with your Heaven-conferred powers and nurturing influences, each to preside over one district, as ministers assisting the Great Worker and Transformer.”

Thus then I may affirm that the religion of China was, and is, a monotheism, disfigured indeed by ignorance and superstition, but still a monotheism, based on the belief in one supreme Being, of whom, and through whom, and to whom are all things.

Very soon that religion became a state-worship, and in doing so it took a peculiar form. The only performer allowed in it is “the One Man,” the sovereign of the nation himself. Its celebration, moreover, is limited to a few occasions, the greatest being that at the winter solstice. Then the service is, or ought to be, an acknowledgment by the Emperor, for himself, his line, and the people, of their obligations to God. It is said of this ceremony that it is “the utmost expression of reverence” and “the greatest act of thanksgiving.” It may have degenerated into a mere formality, but there is the original idea underlying it. It grew probably from the earliest patriarchal worship, though there is no record of that in Chinese literature. The sovereign stands forth in it, both the father and priest of his people. I do not term him the high-priest, for there is no other priest in all the empire. No one is allowed in the same direct manner to sacrifice to God. There never has been in China a priestly class or caste, and I cannot consider this a disadvantage. The restriction of the direct, solemn worship of God has been unfortunate, excluding the people generally from communion with Him,- the highest privilege of man and the most conducive to the beauty and excellence of his whole character; but better this even than a priestly class, claiming to stand between men and God, themselves not better than other men, and in no respect more highly gifted, and yet shutting up the way into the holiest that is open to all, and assuming to be able by rites and performances of theirs to dispense blessings which can only be obtained from the great God with whom all have to do.

Only on one other point in this part of my lecture will I touch: the relation between men and God as their Governor and the connection between the religion and morality. King T’ang, the founder of the Shang dynasty in B.C. 1766, thus spoke:- “The great God has conferred even on the inferior people a moral sense, compliance with which would show their nature invariably right. To make them tranquilly pursue the course which it would indicate is the work of the sovereign.” Much to the same effect spoke Wû, the first king of the Chân dynasty, in 1122:- “He even, to help the inferior people, made for them rulers, and made for them instructors, who should be assisting to God, so as to secure tranquillity throughout the nation.” Thus government is from God and teaching is from God. They are both divine ordinances. The king and the sage are equally God’s ministers, having their respective functions; and they have no other divine right to their positions but that which arises from the fulfilment of their duties. The dynasty that does not rule so as to secure the well-being of the people has forfeited its right to the throne. An old poet, celebrating the rise of the dynasty of which he was a scion, thus sang:-

“Oh ! great is God; His glance on earth He bent,

Scanning our regions with severe intent

For one whose rule the people should content.

The earlier lines of kings had practised ill,

And ruling, ruled not after God’s just will;

He therefore ’mong the states was searching still.”

So it was with the sovereign; and as for the teacher, if he did not set forth aright the will of God, he had no function at all.

See the application of all this to the case of Confucius and the religious character which it imparts to his moral teachings. The treatise of his grandson, to which I have already alluded, commences with this sentence:- “What Heaven has conferred” (on man) “is called his NATURE; an accordance with this nature is called the PATH” (of DUTY); “the regulation of this path is called the SYSTEM OF INSTRUCTION.” Now who ever sought to regulate the path of duty by his instructions as our sage did? In doing so, he taught man indeed to act in accordance with his nature; but accordance with that nature was the fulfilment of the will of Heaven. The idea of Heaven or God as man’s Maker and Governor was fundamental to the teachings of Confucius, and on this account I contend that those who see in him only a moral teacher do not understand him. What he said was with a divine sanction; and they who neglected and disobeyed his lessons were as he said, “offending against Heaven, and had none to whom they could pray.”

And further the account which I have given of the state religion supplies probably the true reason why Confucius generally spoke of Heaven, and seldom used the personal name God. We ought to find the expressions of a devout reverence and submission in such utterances as the following:- “Alas! there is no one that knows me. But I do not murmur against Heaven, nor grumble against men. There is Heaven; that knows me.”

But I hasten on to speak, next and finally, of that other worship-if we should call it so-the sacrifices to ancestors and to others not of the same line as their worshippers.

How this worship took its rise I am unable to say. Herbert Spencer holds that “the rudimentary form of all religion is the propitiation of dead ancestors who are supposed to be still existing, and to be capable of working good or evil to their descendants.” This view is open to the criticism which I made on the Confucian sacrifices generally: that our idea of propitiation is not in them. It is not found either in those to the supreme Being or in those to the dead.

Of course sacrificing to the dead involves a belief in the continued existence of the souls or spirits of men after their life on earth has come to a close, and also that they continue in the possession of their higher faculties, so as to be conscious of the services rendered to them, and to be able to exercise an influence on the condition of their descendants and others in the world.

Sacrificing to the departed great, who were not of the same line as their worshippers, admits of an easy explanation. It is a grateful recognition of the services which they rendered to their own times and for all time. In the Record of Ritual Usages we read, “According to the Institutes of the Sage Kings, sacrifices should be offered to him who had given laws to the people, to him who had persevered to the death in the discharge of his duties, to him who had strengthened the State by his laborious toil, to him who had boldly and successfully met great calamities, and to him who had warded off great evils. Only men of this character were admitted to the sacrificial canon.” Such a sacrificial service has little that is objectionable in it. It is little more than the tribute which a historian pays to the virtues of those whom he commemorates in his writings, and in which his readers cordially join. Nor does this worship interfere with the monotheism of the Chinese religion. The men are not deified. I will give you an instance in point from a hymn which was employed in sacrificing to a very ancient worthy styled Hâu-chî, who was honoured as the father of agriculture. It says,-

“O thou accomplished, great Hâu-chî,

To whom alone ’twas given

To be by what we owe to thee

The correlate of Heaven,

On all who dwell within our land

Grain food didst thou bestow;

’Tis to thy wonder-working hand

This gracious boon we owe.

God had the wheat and barley meant

To nourish all mankind;

None would have fathomed His intent

But for thy guiding mind.”

Confucius has a distinguished place in this sacrificial service, and I used to think that he received in it religious worship, and denounced it. But I was wrong. What he received was the homage of gratitude, and not the worship of adoration. There is a danger of this worship being productive of evil and leading to superstition and idolatry. The most remarkable instance of this that occurs to me is the exaltation for the last three centuries of Kwan Yü, an upright, likable warrior of our third century, to be really, so far as the title is concerned, “the god Kwan,”- the god of war.

But I return to the worship of ancestors. That is insisted on in the Confucian teaching as the consummating tribute of filial piety, the virtue which occupies the first place in the scale of human excellences. A great virtue it is undoubtedly, but it is exaggerated by the Chinese; and the exaggeration has been on the whole perhaps injurious to the prosperity and progress of the nation.

Certain sayings of Confucius have often been pointed out as showing that he was not satisfied in his own mind as to the continued existence of the dead, or that their spirits really had knowledge of the sacrificial services rendered to them; but I will not enter now on a discussion of them. We are not certain how we should understand them, and he was himself strict in the performance of the services. “He sacrificed to the dead,” we are told, “as if they were present, and to the spirits as if they were there.” If he were prevented from being present at such a service, and had to employ another to take his place, he considered his absence to be equivalent to his not sacrificing.

At the sacrifice small tablets of wood with the names of the deceased to whom they were dedicated written on them were set up, and called the spirit-tablets, which the spirits were supposed to take possession of for the time. They were ordinarily in an apartment behind the sacrificial hall, and brought out for the occasion. They were returned to their place when the service was over, and the spirits were supposed to have left the temple for their place. But where was their place? Where and in what condition do the spirits of the departed exist?

For one thing, they are believed to be in heaven, and in the presence of God. A very famous name in China was that of king Wăn, whose career led to his son’s becoming the first sovereign of the Châu dynasty; and of him after his death it was sung,-

“The royal Wăn now rests on high,

In dignity above the sky;

Châu as a state had long been known;

Heaven’s choice of it at last was shown.

Its lords had gained a famous name;

God kinged them when the season came.

King Wăn ruled well when earth he trod;

Now moves his spirit near to God.”

In the same way the emperors of the present Man-chû line speak of their departed fathers. The concluding hymn for the worship of them in the ancestral temple in the canon of 1826 may be thus rendered:-

“Now ye confront, now ye pass by,

Unbound by conditions of place;

Here ye descend, there ye ascend,

Nor leave of your movements a trace.

Still and deep is the chamber behind;

How restful and blessed its space!

Their home have your spirits in heaven,

The shrines there their tablets embrace.

A myriad years their course shall run,

Nor e'er our filial thoughts efface.”

For another thing, the spirits of the departed become tutelary guardians of their posterity, dispensing blessings on them if they pursue the course of well-doing and punishing them if they do wrong, subject, however, in both cases to the will of God.

Time will not permit me to adduce instances in confirmation of this statement, which could easily be done from the records of Chinese history. They are all cases, however, of good sovereigns and men, who, because of their virtuous course on earth, attained at death to heaven and the presence of God, and had the charge there of watching over the interests that had occupied them and been dear to them in life. But what does the Confucian religion of China teach concerning the future state of bad sovereigns and bad men generally? I may almost reply to this question, “Absolutely nothing.” Its oracles are dumb on this interesting and important point. There is no purgatory and no hell in the Confucian literature.

There had grown up even before the time of the Sage a doctrine that the retribution of good and evil takes place in time, and he himself derived no little benefit in his own career from it. The distinction between good and evil is never obscured, nor the different issues of the one and the other. Every moralist writes as if he had been charged, like Isaiah, to “say of the righteous that it shall be well with him, for the reward of his hands shall be given him, and of the wicked, Woe unto the wicked! it shall be ill with him, for the reward of his hands shall be given him.” Similar proclamations resound all along the line of Chinese history; but the good to the righteous, and the ill to the wicked, are only the prosperity of the one class and the overthrow and ruin of the other in their worldly estate. The retribution of both cases takes place, not in the persons of the good or the bad, but in those of their descendants. I have said that this view of providence had arisen in China before the time of Confucius. There is a distinct enunciation of it in one of the appendixes to the Yi-King, the authorship of which is generally, though not, I think, correctly, ascribed to the Sage himself. It is said, “The family that accumulates goodness is sure to have superabundant happiness; the family that accumulates evil is sure to have superabundant misery.” The same teaching appears in the second commandment of our Decalogue. An important and wholesome truth it is that the good-doing and ill-doing of parents are visited on and in their children; but do the sinning parents themselves escape the curse? It is in this form that the subject of future retribution appears among the literati of China, the professed followers of Confucius, at the present day. They do not deny the continued existence of the spirit after death, and they present their sacrifices or offerings to their ancestors, but it is with little or no consideration of whether their lives were good or bad. Those offerings have become unmeaning forms.

One of the most interesting ceremonies conducted at the capital of China is that in which the emperors perform a sacrificial service twice a year to the spirits of the emperors of all the dynasties before their own. In the canon of 1826, the sovereigns sacrificed to, from Fu-hsî in the thirty-fourth century before Christ down to the close of the Ming dynasty in 1643, amount to a hundred and eighty-eight. These are not nearly all the sovereigns that have reigned during the long period of five thousand years or thereabouts. What names are admitted and what are rejected depends on the reigning emperor and on the members of the Board of Rites. Shih Hnang Ti of Ch’in, the great enemy of Confucianism, does not appear, nor sovereigns who proved the ruin of their dynasties. Success seems to be the chief consideration ensuring a place. The second and greatest of the reigning line laid it down as a rule for his canon-makers that the character of the sovereigns whom they admitted was not to be too critically examined.

Thus the entire silence of the religion of China with regard to the future of the bad is an unsatisfactory feature in it. The only evil issue of an evil course which it intimates, and that not very distinctly, is to be excluded from sharing in the sacrifices to the dead, the force of which as a motive to virtuous conduct I am unable to appreciate.

I have done, having fulfilled the task which I undertook as well as I am able at present to attain to. I think you will judge of Confucius pretty much as I do. His appearance well deserves to be commemorated as an era in the history of his nation; and whatever there is of good and strength in it is mainly due to him. That there is no little of both may safely be inferred from the long continuance of its national history and the growth of its population. It is what it is, politically, socially, and morally, through the teachings of its Sage. It would have been better if those had been allowed to have the sole occupancy of it. But Tâoism before Confucius and since, and Buddhism since our first century, have been sowing their tares in it. I say so with deference to those who think more highly of those systems than I am able to do. And now in this later time our religion, our commerce, our science and arts, our manners and customs, have all found their way to the empire. Will it be to improve and regenerate it, or to weaken and ruin it? The former will be the case if we act to it according to the golden rule of Confucius, and do to the Chinese as we would have them do to us, and according to the still loftier maxim of Lâo-tsze, and overcome their evil by our good. I look forward to the future of China with considerable anxiety, but with more of hope.

理雅各教授遺影。圖片來源: The Stewart Lockhart Photographic Archive, on loan from George Watson’s College to the Scottish National Photography Collection